Kleve

| Cleves | ||

|---|---|---|

Schwanenburg | ||

| ||

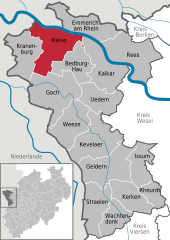

Cleves Location of Cleves within Kleve district   | ||

| Coordinates: 51°47′15″N 6°8′7″E / 51.78750°N 6.13528°ECoordinates: 51°47′15″N 6°8′7″E / 51.78750°N 6.13528°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Admin. region | Düsseldorf | |

| District | Kleve | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Sonja Northing (non-party) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 97.79 km2 (37.76 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 12 m (39 ft) | |

| Population (2016-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 51,047 | |

| • Density | 520/km2 (1,400/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 47533 | |

| Dialling codes | 0 28 21 | |

| Vehicle registration | KLE | |

| Website | www.kleve.de | |

Cleves (German: Kleve; Dutch: Kleef; French: Clèves; Latin: Clivia) is a town in the Lower Rhine region of northwestern Germany near the Dutch border and the river Rhine. From the 11th century onwards, Cleves was capital of a county and later a duchy. Today, Cleves is the capital of the district of Cleves in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The city is home to one of the campuses of the Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences.

Territory of the municipality

The territory of Cleves comprises, next to the innercity, of fourteen villages and populated places:

Bimmen, Brienen, Donsbrüggen, Düffelward, Griethausen, Keeken, Kellen, Materborn, Reichswalde, Rindern, Salmorth, Schenkenschanz, Warbeyen and Wardhausen.

History

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The native name Kleff probably derives from Middle Dutch clef, clif ‘cliff, bluff’, referring to the promontory on which the Schwanenburg castle was constructed. Since the city's coat of arms displays three clovers (German Klee, Low German Kliev), the city's name is sometimes linked by folk etymology to the clover, but the corresponding Dutch word is klever.[2] Notably, Kleve was spelled with a c throughout its history until spelling reforms introduced in the 1930s required that the name be spelled with a k. As of 2008, the CDU announced ambitions to return the name to its original spelling.

The Schwanenburg (English: Swan Castle), where the dukes of Cleves resided, was founded on a steep hill. It is located at the northern terminus of the Kermisdahl where it joins with the Spoykanal, which was previously an important transportation link to the Rhine. The old castle has a massive tower, the Schwanenturm 180 feet (55 m) high, that is associated in legend with the Knight of the Swan, immortalized in Richard Wagner's Lohengrin.

Medieval Kleve grew together from four parts — the Castle Schwanenburg, the village below the castle, the first city of Kleve on the Heideberg Hill, and the Neustadt ("New City") from the 14th century. In 1242 Kleve received city rights. The Duchy of Cleves, which roughly covered today's districts of Kleve, Wesel and Duisburg, was united with the Duchy of Mark in 1368, was made a duchy itself in 1417, and then united with the neighboring duchies of Jülich and Berg in 1521, when John III, Duke of Cleves, married Mary, the heiress of Jülich-Berg-Ravenburg.

.jpg)

Kleve's most famous native is Anne of Cleves (1515–1557), daughter of John III, Duke of Cleves and (briefly) wife of Henry VIII of England. Several local businesses are named after her, including the Anne von Kleve Galerie.

The local line became extinct in the male line in 1609, leading to a succession crisis in the duchies. After the Thirty Years' War, in 1648, the succession dispute was finally resolved with Cleves passing to the elector of Brandenburg, thus becoming an exclave of the territory of Prussia.

During the Thirty Years' War the city had been under the control of the Dutch Republic, which in 1647 had given Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen administrative control over the city. He approved a renovation of the Schwanenburg in the baroque style and commissioned the construction of extensive gardens that greatly influenced European landscape design of the 17th century. Significant amounts of his original plan for Kleve were put into effect and have been maintained to the present, a particularly well-loved example of which is the Forstgarten.

.jpg)

The mineral waters of Kleve and the wooded parkland surrounding it made it a fashionable spa in the 19th century. At this time, Kleve was named "Bad Cleve" (English "baths of cleves"). Though no longer drawing visitors for its baths, Kleve remains a popular destination, and tourism remains a primary factor in the local economy.

During World War II Kleve was the site of one of the two radio wave stations that served the Knickebein radio targeting system. Luftwaffe bombers used signals from Kleve and a second station at Stolberg to navigate to British targets.[3] The Knickebein system was eventually jammed by the British. It was replaced by the higher frequency X-Gerat system, which used transmitter stations located on the channel coast of France.

Kleve was heavily bombed during the Second World War, with over 90% of buildings in the city severely damaged. Most of the destruction was the result of a raid late in the war in 1945, conducted at the request of Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks in preparation for Operation Veritable. Horrocks recounted his decision in the 1973 television documentary The World at War:

Then they came to me and they said, “Do you want Cleves taken out?” By "taken out" they meant the whole of the heavy bombers putting on to Cleves. Now, I knew that Cleves was a very fine old historical German town. Anne of Cleves, one of Henry VIII’s wives, came from there. I knew that there were a lot of civilians in Cleves, men, women and children. If I said no, they would live. If I said yes, they would die. A terrible decision you’ve got to take. But everything depended on getting a high piece of ground at Materborn. The German reserves would have to come through Cleves, and we would have to breach the Siegfried Line and get there. And your own lives, your own troops, must come first, so I said yes, I did want it taking out. But when all those bombers went over, the night just before zero hour, to take out Cleves, I felt a murderer. And after the war I had an awful lot of nightmares, and it was always Cleves.[4]

Horrocks later said that this had been "the most terrible decision I had ever taken in my life" and that he felt "physically sick" when he saw the bombers overhead. [5] [6]

As a result of the bombing, relatively little of the pre-1945 City remains. Those structures spared include a number of historic villas built during the heyday of Spa Bad Kleves, and they are located along the B9 near the Tiergarten. Of those buildings destroyed, many were reconstructed, including most of the Schwanenburg and the Stiftskirche, the Catholic parish church. Constructed on high ground, many of these landmarks can be seen from the surrounding communities.

Since 1953 there has been a broadcasting facility for FM radio and television from regional broadcaster WDR near Kleve. The current aerial mast was brought into service in 1993. The steel tube mast rises 126.4 metres high and has a diameter of 1.6 metres. It is stabilized by guy wires attached at 57 and 101.6 metres height.

Following the Second World War important employers in the area were associated with the Wirtschaftswunder, and included the XOX Bisquitfabrik (XOX Biscuit Factory) GmbH and the Van den Berg'schen Margerinewerke (Margarine Union), that manufactured biscuits and margarine. Another important employer was the Elefanten-Kinderschuhfabrik (Elefant Children's Shoes Factory).

Retail has become an increasingly important industry, particularly after the institution of the euro in 2002. Dutch citizens often cross the border to patronize local retailers, drawn by cost savings they can get in Germany. A great deal of the euros spent on shopping in Kleve originate from the Netherlands. Lower costs of real estate have attracted a wave of Dutch citizens, who purchased houses in the area to make it their homes.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1815 | 6,517 | — |

| 1832 | 6,990 | +7.3% |

| 1867 | 9,209 | +31.7% |

| 1898 | 13,724 | +49.0% |

| 1910 | 18,135 | +32.1% |

| 1920 | 19,453 | +7.3% |

| 1930 | 21,561 | +10.8% |

| 1939 | 21,784 | +1.0% |

| 1950 | 28,740 | +31.9% |

| 1960 | 21,129 | −26.5% |

| 1970 | 45,675 | +116.2% |

| 1980 | 45,899 | +0.5% |

| 1990 | 47,191 | +2.8% |

| 2000 | 48,926 | +3.7% |

| 2010 | 49,794 | +1.8% |

| 2013 | 50,650 | +1.7% |

Census data

According to the Statistical Yearbook of Cleves[7] as of 2013, 50,650 people resided in the city. The population density was 517.9 people per square kilometer. 86.7% of the residents had the German citizenship (including residents with dual citizenship) and 10.1% another EU citizenship (5.6% Dutch and 2.9% Polish).

In the city, in 2013, the population was distributed with 19.7% under the age of 21, 25.6% from 21 to 40, 29.7% from 41 to 60, 20.1% from 61 to 80, and 4.9% who were 81 years of age or older. For every 100 females, there were 96.7 males. For every 100 females age 21 and over, there were 93.9 males.

81.3 of the citizens lived in households without children under the age of 18, 9.2% with one child, 6.1% with two children, 1.7% with three children, and 0.1% with four children or more.

Religion

As the rest of the Lower Rhine region, Cleves is a predominantly Roman Catholic city.[7] The city is part of the Diocese of Münster. 61.1% of the residents are Roman Catholics, 14.4% Protestant, and 24.6% "Other". The largest section of this group are residents without any religious affiliation, but there are also sizeable Russian Orthodox and Muslim communities in Kleve.

The synagogue of Cleves was destroyed during Kristallnacht and is today commemorated on the Synagogenplatz (Synagogue square) on which the building´s outline can be seen. The fifty killed Jewish citizens of Cleves are remembered with signs that tell their names, and dates and places of death.[8]

Gallery of churches in Kleve

- Bimmen, St. Martin

Düffelward, St. Maurice

Düffelward, St. Maurice- Griethausen, St. Martin

- Keeken, St. Mariae Himmelfahrt

Keeken, Reformed church

Keeken, Reformed church Kellen, St. Willibrord

Kellen, St. Willibrord Kleve, St. Mariae Himmelfahrt

Kleve, St. Mariae Himmelfahrt Materborn, St. Anna

Materborn, St. Anna- Rindern, St. Willibrord

- Schenkenschanz, Reformed church

Government

City Council

Cleves' local politics were since the mid-19th century until 1933 dominated by the Catholic Centre Party. This situation continued with the Christian Democratic successor party CDU after the Second World War, in spite of resettled, mostly Protestant, displaced. Until 2004 the CDU controlled an absolute majority of the city council.

Today, Cleves is governed by a coalition of CDU and the Green Party. Since the last local elections on 25 May 2014 the following parties are represented in Cleves' city council. In addition to nationwide parties, Offene Klever (Open Cleves) has a number of seats.

| Party | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| CDU (Christian Democrats) | 39.52 | 17 |

| SPD (Social Democrats) | 28.96 | 13 |

| Green Party | 13.10 | 6 |

| Open Cleves | 11.00 | 5 |

| FDP (Liberals) | 7.42 | 3 |

| Participation: 42.32% | ||

The next local elections are scheduled for 2020.

Mayor

The mayor of Cleves is since September 2015 Sonja Northing (without party affiliation), who won the election with 64.5%. Her candidacy was supported by Social Democrats, Open Cleves and FDP. Northing's opponents were Christian Democrat Udo Janßen (23.4%) and the Green candidate Artur Leenders (12.1%). The participation was 40.89%. Northing is the first mayor of Cleves since World War II, who is not a CDU member.[9]

The next mayor elections are scheduled for 2020.

Language and dialect

The native language of Cleves and much of the Lower Rhine region is a Dutch dialect known as Cleverlander (Dutch: Kleverlands, German: Kleverländisch), most closely related to South Guelder, but the official language is German which is dominant among the younger generation.

Because of its geographical location directly at the Dutch-German border, there is a strong overlap in culture and language. One example of this is Govert Flinck (1615 – 1660), who although born in Cleves, established himself as a Dutch artist. On the other hand the Dutch artist Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803 – 1862) settled down in Kleve and became a successful landscape painter. His works are collected by and exhibited in the local museum for his and other's romantic paintings 'Haus Koekkoek'.

Twin cities

Cleves is twinned with

Notable people

- Joseph Beuys, artist, grew up in Kleve.

- Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII of England.

- Marie of Cleves, mother of king Louis XII of France.

- Marie Eleonore of Cleves, Duchess of consort Prussia.

- Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, baron de Cloots, (1755-1794), politician and French revolutionary, born in Kleve.

- Barbara Hendricks, (born 1952), politician (SPD), current German Minister for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, born in Kleve.

- Karl Leisner, (1915-1945), Roman Catholic martyr and beatified by Pope John Paul II, grew up in Kleve.

- Joachim Murat, (1767-1815), Grand Duke of Berg and Cleves during the Napoleonic years.

- Duke Englebert of Cleves, (1462-1506), Count of Nevers.

- Govaert Flinck, (1615-1660), Dutch painter who worked in Kleve.

- Tina Theune, (born 1953), former national coach of the German women's national football team.

- Heinrich Berghaus (1797-1884), cartographer.

- Klaus Steinbach (born 1953), swimmer and president of the Nationales Olympisches Komitee.

- Willi Lippens (born 1945), football player.

- Jürgen Möllemann (1945-2003), politician (FDP), Federal Minister.

References

- ↑ "Amtliche Bevölkerungszahlen" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ↑ L. Grootaers & G.G. Kloeke, eds., Taalatlas van Noord- en Zuid-Nederland (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1939): .

- ↑ "Most Secret War". R.V. Jones

- ↑ The World at War - Episode Nineteen: "Pincers" - Thames Television 1974

- ↑ Note, Kleve was bombed by a force of 295 Lancasters and 10 Mosquitoes of No. 1 and No. 8 Groups.

- ↑ The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book, By Chris Everitt, Martin Middlebrook

- 1 2 "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2013" (PDF). Stadt Kleve. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Sehenswürdigkeiten: Synagogenplatz". Stadt Kleve. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ↑ Matthias Grass: Erdrutsch-Sieg für Sonja Northing, Rheinische Post Kleve, September, 14th 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kleve. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kleve. |