Cinderella (1997 film)

| Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella | |

|---|---|

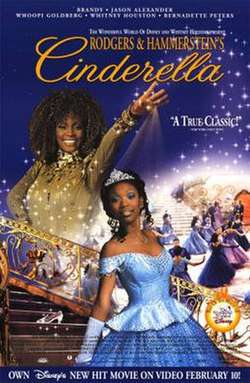

Home video promotional image, featuring Houston and Brandy in costume as their respective characters. | |

| Genre |

Musical Fantasy |

| Based on |

Cendrillon by Charles Perrault Cinderella by Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Written by | Robert L. Freedman |

| Directed by | Robert Iscove |

| Starring |

Whitney Houston Brandy Jason Alexander Whoopi Goldberg Bernadette Peters Veanne Cox Natalie Desselle Victor Garber Paolo Montalban |

| Theme music composer |

Richard Rodgers Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) |

Whitney Houston Debra Martin Chase Craig Zadan Neil Meron Robyn Crawford David R. Ginsburg |

| Running time | 88 minutes |

| Production company(s) |

Walt Disney Television BrownHouse Productions Storyline Entertainment |

| Distributor | Buena Vista Television |

| Budget | $12 million |

| Release | |

| Original network | ABC |

| Original release | November 2, 1997 |

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella[1] (also known as simply Cinderella)[2][3][4][5] is a 1997 American musical fantasy television film[6] produced by Walt Disney Television, directed by Robert Iscove and written by Robert L. Freedman. Based on the French fairy tale by Charles Perrault, the film is the second remake and third version of Rodgers and Hammerstein's television musical, which originally aired in 1957. The film tells the story of a young woman who is mistreated by her stepfamily until her fairy godmother encourages and enables her to attend the kingdom's ball, where she meets and ultimately falls in love with the prince.[7] Adapted from Oscar Hammerstein II's book, Freedman modernized the script in order to appeal to more contemporary audiences by updating its main characters and themes, particularly re-writing the title character into a stronger heroine, while remaining faithful to the original material. Co-produced by Whitney Houston, who also appears as Cinderella's Fairy Godmother, the film stars Brandy in the titular role and features a racially diverse cast that consists of Jason Alexander, Whoopi Goldberg, Bernadette Peters, Veanne Cox, Natalie Desselle, Victor Garber and Paolo Montalban.

Following the success of the 1993 television adaptation of the stage musical Gypsy (1959), Houston approached Gypsy's producers Craig Zadan and Neil Meron about producing and starring in a remake of Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella for CBS. However, development on the project was continuously delayed, during which time the network ultimately became disinterested. By the time the film was greenlit by Disney and ABC several years later, Houston felt that she had since outgrown the role of Cinderella and offered it to Brandy in favor of playing the character's Fairy Godmother instead. The decision to use a color-blind approach to casting the film's characters originated among the producers as a means of reflecting the ways in which society had evolved by the 1990s, with Brandy becoming the first black actress to portray Cinderella on screen. Among the most significant changes made to the musical, several songs from other Rodgers and Hammerstein productions were interpolated into the film to augment its original score, including new musical material for Peters, Brandy, Montalban and Houston's characters. With a production budget of $12 million, Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella ranks among the most expensive films ever made for television.

Heavily promoted to re-launch the anthology series The Wonderful World of Disney, Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella premiered on ABC on November 2, 1997 to generally lukewarm reviews from entertainment critics. While most reviewers praised the film's costumes, sets and supporting cast, particularly the performances of Peters, Alexander, Goldberg and Montalban, television critics were divided over Brandy and Houston's acting, as well as Disney's more feminist approach towards the film's title character. Cinderella was a significant ratings success, airing to 60 million viewers and establishing itself as the most-watched television musical in decades. The telecast remained the most-watched program of the entire week, earning ABC its highest Sunday-night ratings in 10 years. Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was nominated for several industry awards, including seven Primetime Emmy Awards, winning one for Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program. The program's success inspired Disney and ABC to produce several similar musical projects for the network. Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella is regarded by critics as a groundbreaking film due to the diversity of its cast.

Plot

Cinderella's Fairy Godmother (Whitney Houston) explains that nothing is impossible in this magical kingdom. In the village, Cinderella (Brandy) struggles under the weight of the purchases of her ill-tempered Stepmother (Bernadette Peters) and her spiteful stepsisters Minerva (Natalie Desselle-Reid) and Calliope (Veanne Cox). Cinderella's imagination wanders ("The Sweetest Sounds"). Disguised as a peasant, Prince Christopher (Paolo Montalban) is also strolling through the marketplace. The two meet when the Prince rushes over to help Cinderella after she is nearly run over by the royal carriage. They begin to talk and realize they are both dissatisfied with their sheltered lives. She is charmed by his sincere, direct nature, while he is drawn to her naïve honesty and purity. Their conversation is cut off when Cinderella's Stepmother scolds her for talking to a stranger. The Prince reluctantly leaves, but tells Cinderella that he hopes to see her again.

Back at the palace, the Prince tries to explain his sense of isolation to his loyal valet Lionel (Jason Alexander), who frantically upbraids him for his clandestine venture into the village. He learns that his mother Queen Constantina (Whoopi Goldberg) is making preparations for a ball where he is to select a suitable bride from all the eligible maidens in the kingdom. The Prince wishes to fall in love the old-fashioned way; his father King Maximilian (Victor Garber) seems to understand, but the Queen will not listen, and dispatches Lionel to proclaim that "The Prince is Giving a Ball." Meanwhile, the Stepmother is determined to see one of her graceless, obnoxious and self-indulgent daughters chosen as the Prince's bride at the ball; she begins to plan their big night. Cinderella wonders if she, too, might go to the Prince's ball. Finding the idea humorous, Stepmother reminds Cinderella of her lowly station and warns against dreams of joy, success, and splendor. Disappointed, Cinderella dreams of a world away from her cold and loveless life ("In My Own Little Corner").

While the preparations for the ball are underway, the Prince confronts his parents, who refuse to cancel it. Using his diplomatic skills, Lionel creates a compromise between the Prince and his parents: the Prince will go to the ball, but if he doesn't meet a suitable bride that night then he gets to seek his true love in his own way. At the same time, Stepmother drills Minerva and Calliope on how to ensnare the Prince and warns them to hide their flaws at all costs. As Cinderella questions the meaning of love and romance, Stepmother reminds the girls that going to the ball has nothing to do with finding love and everything to do with getting a husband by any means necessary ("Falling in Love With Love"). On the big night, Stepmother, Minerva and Calliope depart for the palace in their garish gowns and leave a teary-eyed Cinderella home alone.

In response to Cinderella's tearful wish to go to the ball, the beautiful Fairy Godmother appears and encourages Cinderella to start living her dreams ("Impossible"). She transforms a pumpkin into a gilded carriage, rats into a coachman and footmen, mice into regal horses, and Cinderella's simple clothes into a gorgeous blue gown with a bejeweled tiara and glass slippers. The Fairy Godmother cautions Cinderella that magic spells have time limits, and she must leave the palace before the stroke of midnight. Cinderella finally begins to believe "It's Possible" for her dreams to come true.

At the ball, Lionel dutifully delivers eligible maidens to the Prince on the dance floor, and Stepmother fiendishly schemes behind the scenes on behalf of her daughters. The Prince is unimpressed by Minerva, who breaks out in an itchy rash, and Calliope, who snorts uncontrollably at everything the Prince says. Suddenly, Cinderella appears at the top of the staircase, and the Prince has eyes only for her. Soon they are waltzing together ("Ten Minutes Ago"), and the "Stepsisters Lament" over their bad luck. The King and Queen are intrigued by this mysterious princess. Embarrassed by their questions about her background, Cinderella escapes to the garden in tears, where Fairy Godmother magically appears for moral support. The Prince follows Cinderella into the garden and the pair wonders if their newfound love is real ("Do I Love You Because You're Beautiful?"). Just as they share their first kiss, the tower clock begins to strike midnight. Cinderella flees before her gown changes back into rags, leaving behind on the palace steps a single clue to her identity: a sparkling glass slipper. The Prince tries to follow her but gets held up by the crowd at the ball.

Stepmother and the Stepsisters return home telling exaggerated stories about their glorious adventures with the Prince. They speak in envious tones of a mysterious "Princess Something-or-other" who, they concede, also captured the Prince's attention. When Cinderella "imagines" how an evening at the ball would be "A Lovely Night", Stepmother recognizes her as the mystery princess. She coldly reminds Cinderella that she is common-born and should stop dreaming about a life that she will never have. In the face of such cruelty, a devastated Cinderella prays to her late father for the strength to find a happier life. Her Fairy Godmother reappears and advises her to share her feelings with the Prince.

Meanwhile, Lionel and the heartbroken Prince seek the maiden who lost the glass slipper, but none of the eligible female feet in the kingdom measure up. The Prince and Lionel finally arrive at the Stepmother's cottage. The Stepsisters and even Stepmother try to fit their feet into the delicate slipper, but to no avail. As the dispirited Prince prepares to leave, he finds Cinderella attempting to run away, only to have her baggage trampled by the royal coach. He recognizes her from their first meeting in the market and, knowing that he has finally found his true love, places the slipper on her foot: it fits.

Cinderella and the Prince marry under the approving eye of King Maximilian and Queen Constantina, as the gates of the palace slam shut on Cinderella's stepfamily; left outside as the Prince and his new Princess start their lives together. The Fairy Godmother blesses the royal couple with the message that "There's Music in You", as they are cheered by their joyful subjects.

Cast

Order of credits adapted from Variety magazine and the British Film Institute:[2][8]

- Whitney Houston as Fairy Godmother

- Brandy as Cinderella

- Jason Alexander as Lionel, the Prince's butler and valet

- Whoopi Goldberg as Queen Constantina,[9] the Prince's mother

- Bernadette Peters as Cinderella's stepmother

- Veanne Cox as Calliope, Cinderella's stepsister

- Natalie Desselle as Minerva, Cinderella's stepsister

- Victor Garber as King Maximillian,[9] the Prince's father

- Paolo Montalbán as Prince Christopher

Production

Origins and development

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was the third screen version of the musical.[10][11] Songwriters Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II originally wrote Cinderella as a musical exclusively for television starring Julie Andrews,[12] which aired in 1957 to 107 million viewers.[13] The telecast was remade in 1965 starring Lesley Ann Warren,[14][15] which featured significant modifications from the original.[16] This adaptation aired annually on CBS from 1965 to 1972.[17] The idea to remake Cinderella for television a second time originated as early as 1992, at which time producers Craig Zadan and Neil Meron first approached the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization about obtaining the rights to the production.[17] Further development was inspired by the success of CBS' adaptation of the stage musical Gypsy (1993) starring Bette Midler which,[18][19] in addition to being credited with reviving interest in the genre,[19] Zadan and Meron had also produced;[20] CBS executive Jeff Sagansky asked Zadan and Meron to start brainstorming ideas for a follow-up project shortly after Gypsy aired.[21] The day after Gypsy's original broadcast, singer Whitney Houston's agent Nicole David contacted the producers to ask if they were interested in developing any similar musical projects starring her client,[22][23][24] to whom they suggested Cinderella with Houston playing the title role as it was originally intended to be a star vehicle for the singer.[14][25] CBS originally intended to air the completed film before the end of the 1994-1995 television season.[19] However, the project was continuously delayed; CBS grew disinterested in favor of other titles by 1996,[23] while Houston herself had already been committed to other film and music projects.[22][24] Zadan explained that Houston was "so in demand at the time. She had so many other concrete things that she was doing that 'Cinderella" took a back seat and, as the time went on and executives started changing at CBS".[21] The singer eventually aged to the point at which she no longer felt suitable for the role of Cinderella.[25] Houston explained that by the time she became a wife and mother, she was not "quite feeling like Cinderella" anymore, believing that portraying the innocence associated with the character would have required significant "reaching" for her as an actress,[9] an opinion she shared with producing partner Debra Martin Chase who likened the situation to singer Diana Ross appearing "a little old" for the role of Dorothy in The Wiz (1978).[21] Furthermore, the general public had ceased to view Houston "as an innocent young girl."[26] Had Houston accepted the role, she would have been the first black actress to portray Cinderella on screen.[19]

Disney was interested in re-launching The Wonderful World of Disney, a long-time anthology program which had long been on hiatus.[27] Seeking to resurrect the series using "a big event", Disney CEO Michael Eisner approached Zadan and Meron about any projects they might have, to whom they suggested Cinderella starring Houston; Eisner immediately green-lit the project.[21] In addition to Eisner, studio executives Charles Hirschorn, Joe Roth and Jamie Tarses quickly expressed interest.[22] After departing from CBC and relocating their production company, Storyline Entertainment, to Disney Studios,[23] Zadan and Meron re-introduced the dormant project to Houston.[25] Agreeing that role of Cinderella required a certain "naivete ... that's just not there when you're 30-something",[22] the producers suggested that she play Cinderella's Fairy Godmother instead,[25] a role Houston accepted because it was a "less demanding" part that required less time and effort to film.[28] For the lead role of Cinderella, Houston personally recommend her close friend, then 18 year-old singer Brandy.[25] Her first major film role,[29] Brandy had been starring on the sitcom Moesha but was still relatively new to television audiences at the time, despite her success as a recording artist.[24][30][31] Houston felt that Brandy possessed the energy and "wonder" to play the titular role convincingly, admitting that their fictional relationship as godmother and goddaughter translates "really well on-screen because it starts from real life";[9] when Houston telephoned Brandy to offer her the part, she introduced herself as her fairy godmother.[22][32] Brandy, who identified "Cinderella" as her favorite childhood fairy tale,[24] became the first person of color to portray the character,[22][33] with both Brandy and Houston becoming the first African-American actresses to play their respective roles in any screen adaptation of the fairy tale,[1][34] although an all-black re-telling of the "Cinderella" story set in 1943 Harlem, New York entitled Cindy had previously been released in 1978.[35][36]

Brandy likened being hand-selected for the role by someone whom she considers to be her mentor to a real-life fairy tale,[37] feeling that being cast simply "made sense" at the time because she had already had both a singing and acting career, in addition to relating to the character of Cinderella in several different ways.[38] The fact that the character is typically depicted as white did not discourage her from accepting the role or pursuing her dreams during her childhood.[39] Having grown up like most watching mainly Caucasian actresses portray Cinderella, Houston felt that 1997 was "a good time" to finally have a woman of color cast as the titular character, claiming the choice to use a multi-cultural cast "was a joint decision" among the producers.[40] The producers agreed that "each modern generation [should] have their own 'Cinderella'."[21] Executive producer Debra Martin Chase, Houston's producing partner, explained that she and Houston had grown up watching and enjoying Warren's portrayal of Cinderella but eventually "realized we never saw a person of color playing Cinderella", explaining, "To have a black Cinderella with a pretty face and braids is just something. I know it was important for Whitney to leave this legacy for her daughter."[34] Chase hoped that the film's reflection of a changing society "will touch every child and the child in every adult",[24] insisting that "children of all colors dream."[32]

Robert Iscove was enlisted as director,[17] with Chris Montan and Mike Moder co-producing alongside Zadan and Meron;[22] Houston was retained as an executive producer, alongside Chase.[25] The film was co-produced by Walt Disney Telefilms, Storyline Entertainment and Houston's own production company BrownHouse Productions,[17] becoming the latter's first project and Houston's debut as an executive producer.[9][24] The film has a total of five executive producers.[8] According to Zadan and Meron, Houston remained heavily involved in all of the film's production aspects despite being relegated to a supporting role, retaining approval over all creative elements, particularly the film's multiracial cast,[40] the first time the story was adapted for a multi-ethnic cast.[9] Zadan agreed that the film had been conceived as "multi-ethnic from the very beginning",[25] with the producers hoping that this would contribute to the film's "universal appeal" and interest children of all ethnicities.[22] In addition to developing a strong relationship with each other, the producers established a good relationship with the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization and its president Ted Chapin.[21] Although they were originally concerned that the organization would dismiss the idea of the film featuring a multi-cultural cast, they were surprised when the company did not contest the idea whatsoever.[21] One Disney executive would have preferred to have a white Cinderella and black Fairy Godmother and suggested singer-songwriter Jewel for the titular role, explaining, "It'll still be multicultural".[21] The producers refused,[41] proclaiming, "absolutely not. The whole point of this whole thing was to have a black Cinderella."[21] Zadan maintains that Brandy was the only actress they had considered for the role, elaborating, "it's important to mention because it shows that even at that moment there was still resistance to having a black Cinderella. People were clearly still thinking, 'Multicultural is one thing, but do we have to have two black leads?"[21] Mary Rodgers and James Hammerstein, relatives of the original composers, also approved this casting decision, with Mary maintaining that the production remains "true to the original" despite contemporary modifications to its cast and score,[40] and James describing the film as "a total scrambled gene pool" and "one of the nicest fantasies one can imagine.''[25] James also believes Hammerstein would have approved of the color-blind casting, claiming he would have asked why the process took as long as it did.[17] Meron believes that the organization was so open due to Houston's involvement, explaining, "Whitney was so huge at that time; to a lot of executives she was popular entertainment as opposed to being defined by her race."[21]

Writing and themes

Television writer Robert L. Freedman became involved with the project as early as 1993.[21] Although he had not written a musical before, Freedman was fond of Warren's version and drawn to the opportunity to work with Zadan and Meron, whose plans to remake Cinderella he had first read about in a Variety article.[21] Aware that the film could potentially be groundbreaking, Freedman, Zadan and Meron collaborated on several new ideas for the remake, among them ensuring that Cinderella "was defined by more than falling in love", providing her with her own story arc that is beyond simply finding a love interest.[21] The Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization allowed the filmmakers an unusual amount of freedom to modify the musical's script, among these changes making Cinderella a more active heroine;[42] Meron credits Freedman with "giv[ing] her a little bit more of a backbone", ultimately developing the character into a more independent woman.[21] Instead of making each character more modern, Zadan opted to "contemporize the qualities of the characters" instead.[25] Freedman was more concerned with writing a film suitable for young girls in the 1990s than writing a multi-cultural film, inspired by stories about his wife being affected by womens' representation in films when she was growing up.[21] In a conscious decision to update the fairy tale for a modern generation, Freedman sought to deconstruct the messages young girls and boys were subjected to in previous versions of the fairy tale, explaining, "We didn't want the message to be 'just wait to be rescued",[43] and thus altered the story to "reflect current ideas about what we should be teaching children."[42] Attempting to eliminate the element that Cinderella is simply waiting to be rescued by the prince, Freedman explained, "I'm not saying that it's the most feminist movie you'll ever see, but it is compared the other versions."[21] His efforts apply to both Cinderella and the prince; while Cinderella pines for independence from her stepfamily and actively disagrees with her stepmother's opinions about gender roles in marriage, the prince protests the idea of being married off to simply anyone his parents choose.[43]

Freedman continuously re-wrote the script between 1993 and 1997, particularly concerned about whether or not Houston would like his teleplay.[21] Despite quickly earning approval from the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization,[17] Houston typically took longer to make decisions, and although the producers sent and continuously reminded her about the script, it remained unread for several months.[21] Since Houston was still slated to play Cinderella at the time, production was unable to proceed without her involvement.[21] In a final attempt to earn Houston's approval, Meron and Zadan enlisted Broadway actors to perform a read-through for the singer, namely La Chanze as Cinderella, Brian Stokes Mitchell as the prince, Theresa Meritt as the Fairy Godmother and Dana Ivey as the Stepmother.[21][41] They hosted the table-read at the Rihga Royal Hotel in New York City, one of Houston's favorite locations at the time.[21] Houston arrived at the reading several hours late, by which time some of the actors had grown frustrated and weary.[21] Houston remained silent for most of the reading, barely engaging with the participants until the end of the table read when she finally declared her approval of the script and eventually sent the actors flowers to apologize for her tardiness.[21] Houston believed strongly in the story's positive moral "that nothing is impossible and dreams do come true," encouraging the filmmakers to imbue their version of Cinderella "with a 90s sensibility but to remain faithful to the spirit of the original."[44] Freedman identified Houston's eventual re-casting as the Fairy Godmother as a moment that instigated "the next round of rewriting",[21] adapting her version of the character into a "worldly-wise older sister" to Cinderella, as opposed to the "regal maternal figure" that had been depicted prior.[25] Houston described her character as "sassy, honest and very direct ... all the things that you'd like a godmother to be."[9] Houston found the most impressive part of the remake to be "the lessons youngsters can learn about dreams and self-image".[9]

According to Ray Richmond of Variety, Freedman's teleplay is faster in pace and contains more dialogue than previous versions,[8] although A Problem Like Maria: Gender and Sexuality in the American Musical author Stacy Ellen Wolf believes that the teleplay borrows more from the 1957 version than Joseph Schrank's 1965 re-write version due to sharing much of its humor, dialogue and gender politics with Hammerstein's book.[45] Although his teleplay retains the "cockeyed optimism" of the original, its characters have been imbued with "post-modern models of Oprah-fied in-touchness", according to The New York Times journalist Todd S. Purdum.[25] Despite being more similar to the original musical than the 1965 remake in style and structure, the script's "values and tone" have been updated.[17] The New York Daily News journalist Denene Millner observed that although the remake is "not all that different from the original", its version of Cinderella is more outspoken, the prince is more interested in finding someone he can talk to as opposed to simply "another pretty face", as well as "a hip fairy godmother who preaches self-empowerment" as a result of its "'90s flair".[34] The remake reflected a changing society,[33] containing themes discussing self-reliance and love.[46] According to George Rodosthenous, author of The Disney Musical on Stage and Screen: Critical Approaches from 'Snow White' to 'Frozen', "traces of sexism" were removed from the script in favor of creating "a prince for a new era" while maintaining its "fundamental storyline";[47] this version of the story emphasizes that the prince has fallen in love with Cinderella because she is funny and intelligent, in addition to being beautiful.[45] Freedman granted the prince "a democratic impulse" that drives him to spend time among the citizens of his country in the hopes of better understanding them.[42] Cinderella and the prince are also shown meeting and developing an interest in each other prior to the ball,[43] lessening the "love at first sight" element at the behest of the producers, by having Cinderella and the prince meet and talk to each other first,[42] an idea that would be reused in subsequent adaptations of the story.[43] Cinderella has a conversation with the prince in which she explains that a woman should always be treated "like a person. With kindness and respect", which some critics identified as the studio's attempt to make the film more feminist.[39][43][46] The Oxford Handbook of The American Musical editor Raymond Knapp observed that the thoughtfulness and determination exhibited by Brandy's Cinderella is more similar to Belle from Disney's Beauty and the Beast than previous portrayals of the title character.[48]

Cinderella was provided with a more empowering motive in that her fairy godmother reminds her that she has always been capable of bettering her own situation; she "just didn't know it" yet.[42] According to Entertainment Weekly contributor Mary Sollosi, none of the script's dialogue requires that any of its cast or characters be white,[49] with the film also lacking references to the races or ethnicities of the characters whatsoever.[31] The Los Angeles Times critic Howard Rosenberg wrote that the prince's inability to recognize that some of the women trying on the glass slipper in his search for Cinderella are white as part of "what makes this "Cinderella" at once a rainbow and color-blind, a fat social message squeezed into a dainty, glass slipper of a fable."[50]

Casting

To complete the film's multi-racial cast, the producers recruited performers from various facets of the entertainment industry, spanning Broadway, television, film and music.[44] Casting the Stepmother proved to be particularly difficult for the filmmakers, since the mostly white actresses they were interested in for the part felt uneasy about the prospect of acting cruel towards a black Cinderella; Bette Midler was among the several actresses who declined.[41] Bernadette Peters was ultimately cast as Cinderella's stepmother, her second major villainous role after having appeared in the original Broadway cast of the stage musical Into the Woods (1986) as the Witch.[51] As one of her generation's most prominent Broadway actresses, the role of Peters' stepmother was expanded beyond those of previous versions of the character, in addition to receiving a comical romantic subplot with Lionel.[48] Jason Alexander was cast as the prince's valet Lionel, an entirely new character created for the remake,[14] offering comic relief.[52] Alexander accepted the role despite being paid significantly less than his average salary for a single episode of the sitcom Seinfeld because, in addition to hoping to gain Zadan and Meron's favor for the title role in a potential film adaptation of the musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, he hoped that Cinderella's success would positively impact the future of television musicals.[25] Describing the project as both "a big responsibility" and opportunity, Alexander acknowledged that Cinderella's failure to garner high ratings could potentially threaten the future of musical films altogether.[25] Furthermore, Alexander insisted that Lionel be noticeably different from his Seinfeld character George Costanza, despite Freedman originally writing several jokes that alluded to Alexander's most famous role, prompting him to re-write several of the actor's scenes accordingly.[41] Whoopi Goldberg accepted the role of Queen Constantina because Cinderella reminded her of a time during which television specials were "major event[s] in a kid's life" before the introduction of VHS and home video made such programs re-watchable at virtually any given time, and hoped that the film would "get people in the habit of seeing it" and "become part of the fabric of our lives again."[42] Goldberg found the film's colorful cast to be reflective of "who we are", describing it as "more normal" than using either an all-black or all-white cast.[9] Peters, Alexander and Goldberg had each won Tony Awards for their respective work on Broadway.[53]

Victor Garber, who was cast as King Maximillian, also enjoyed the film's multicultural cast, describing the fact that his character is has an Asian son with an African-American queen as "extraordinary".[54] The actor concluded "There's no reason why this can't be the norm."[9] Garber had just completed filming Titanic (1997), which he jokingly referred to on the set of Cinderella as a film about "a big water tank in Mexico."[41] Despite already being an established actor at the time, Garber's casting in the film helped introduce him to a younger audience.[29] Casting the prince took significantly longer, with Chase likening the process to searching for the individual whose foot fits Cinderella's glass slipper.[10] Auditions were held in both Los Angeles and New York. Several well-known actors auditioned for the role, including Wayne Brady. Antonio Sabato, Jr., Marc Anthony and Taye Diggs, the latter of whom was highly anticipated due to his starring role in the musical Rent at the time.[10] The last actor to audition for the production,[41] Paolo Montalban was ultimately cast as Prince Christopher in his film acting debut;[29] Montalban was an understudy in Rodgers and Hammerstein's musical The King and I at the time.[41] Despite being late for the final day of auditions, Montalban impressed the producers with his singing voice.[41] Montalban enjoyed this version of the prince character because "he isn't just holding out for a pretty girl ... he's looking for someone who will complete him as a person, and he finds all of those qualities in Cinderella."[32] Company alumna Veanne Cox and television actress Natalie Deselle, respectively, were cast as Cinderella's wicked stepsisters.[22] Cosmopolitan's Alexis Nedd wrote that the film's final cast consisted of "Broadway stars, recording artists, relative unknowns, and bona fide entertainment superstars."[41] Due to the well-known cast, tabloids often fabricated stories of the cast engaging in physical confrontations, particularly among Brandy, Houston and Goldberg, which turned out to be false.[42]

This version of Cinderella was the first live-action fairy featuring color-blind casting to be broadcast on television.[55] The diversity of the cast prompted some members of the media to dub the film "rainbow 'Cinderella'",[18][56][57] featuring one of the most diverse ensemble casts to appear on television at the time.[58] Laurie Winer of the Los Angeles Times summarized, "Their casting is not just rainbow, it's over the rainbow--the black queen (Goldberg) and white king (Victor Garber), for instance, produce a prince played by Filipino Paolo Montalban. For her part, Cinderella withstands the company of a white stepsister (Veanne Cox) and a black one (Natalie Desselle), both, apparently, birth daughters of the mother played by Bernadette Peters."[42] A writer for Newsweek believed that Brandy's Cinderella falling in love with a non-black prince reflects "a growing loss of faith in black men by many black women", explaining, "Just as Brandy's Cinderella falls in love with a prince of another color, so have black women begun to date and marry interracially in record numbers."[39] The Sistahs' Rules author Denene Millner was less receptive towards the fact that Brandy's Cinderella falls in love with a non-black prince, arguing, "When my stepson who's 5 looks at that production, I want him to know he can be somebody's Prince Charming."[39]

Music

Freedman's final teleplay was 11 minutes longer than previous adaptations, in turn offering several opportunities for new songs, some of which the producers felt necessary.[47] Disney asked the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization to be as open about changes to the musical's score as they had been about the script and cast.[17] Music producers Chris Montan and Arif Mardin were interested in combining "Broadway legit with Hollywood pop",[17] re-arranging the musical's original orchestration in favor of achieving a more contemporary sound by updating its rhythm and beats.[24][36] Montan, who oversees most of the music for Disney's animated films, had been interested in crossing over into live-action for several years and identified Cinderella as one of the first opportunities in which he was allowed to do so.[22] The musicians were not interested in completely modernizing the material in the vein of the musical The Wiz (1974), opting to simply "freshen" its orchestration by incorporating contemporary rhythms, keyboards and instruments, similar to the way in which the studio approaches animated musicals.[22] Although filmmakers are usually hesitant to interpolate songs from other sources into adaptations of Rodgers and Hammerstein's work, Ted Capin, President of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization,[15] challenged the producers to conceive "compelling reasons" as to why they should incorporate new material into the remake,[59] allowing the filmmakers significant freedom on the condition that the additions remain consistent with the project.[17] Three songs not featured in previous versions of the musical were added to augment the film's score,[52] each of which was borrowed from a different Rodgers and Hammerstein source;[6][14][18][40] these additions are considered to be the most dramatic of the changes made to the musical.[42] "The Sweetest Sounds", a duet Rodgers wrote himself following Hammerstein's death for the musical No Strings (1962) was used to explore the lead couple's initial thoughts and early relationship upon meeting each other in the town square,[25] performing separately until they are united.[47] The filmmakers found this song particularly easy to incorporate.[59]

"Falling in Love With Love", which Rodgers wrote with lyricist Lorenz Hart for the musical The Boys from Syracuse (1938), was adapted into a song for Cinderella's stepmother, a character who seldom sings or expresses her innermost feelings in previous adaptations of the fairy tale.[47][59] She advises her own daughters about love and relationships,[59] warning them not to confuse love with marriage.[25] The filmmakers wanted to prove that the Stepmother is not simply "an evil harridan" but rather a "product of bitter experience",[25] for which Freedman himself suggested "Falling in Love With Love".[42] Despite concerns that Hart's "biting" lyrics would sound too abrasive against the rest of the score, James, Hamerstein's son, was very much open to the idea.[59] While Mary, Rodgers' daughter, was initially against using "Falling in Love With Love", she relented once Peters was cast as the Stepmother,[59] feeling confident that the Broadway veteran would be able to "put a different kind of spin on it."[25] The filmmakers also agreed that it would be wasteful to cast Peters and not allow her to use her signature singing voice.[41] According to Peters, the song demonstrates her character's disappointment in her own life, explaining why she has become increasingly embittered and jealous of Cinderella.[25] Performed while they prepare for the ball,[60] the song was offered "a driving, up-tempo arrangement" for Peters.[61] Although its original melody is retained, the music producers adapted the waltz into a "frenetic Latin-tinged number in duple meter" more suitable for Peters' conniving character.[47][48] The filmmakers agreed that Alexander deserved his own musical number due to his experience as a musical theatre performer, and decided to combine the Steward's "Your Majesties" with the Town Crier's "The Prince is Giving a Ball" from the original musical into a large, elaborate song-and-dance sequence.[59] Broadway lyricist Fred Ebb was recruited to contribute original lyrics to the new arrangement "that melded stylistically with the Hammerstein originals."[59] Despite the fact that Hammerstein's will states that making such alterations to his work are prohibited,[62] James believes his father would have appreciated Ebb's contribution since the songwriter had been known to enjoy collaborating with new lyricists.[59]

With Houston cast as the Fairy Godmother, the role was expanded into a more musical one by having the singer open the film performing a slowed down rendition of "Impossible".[47] Describing herself as familiar with the "flavor" of Rodgers and Hammerstein's music, Houston opted to perform the film's songs simply as opposed to using her signature pop, R&B or gospel approach.[42] Zadan and Meron wanted Houston to end the film singing a wedding song for the newly married Cinderella and Prince Christopher.[42] Although the producers agreed that Houston's character would perform the film's closing number,[59] selecting a song suitable for Houston's renowned vocal abilities proved a challenge since the original musical had not been written this way.[25][59] Few remaining songs in Rodgers and Hammerstein's repertoire were deemed appropriate until they re-discovered "There's Music in You", a little-known song from the film Main Street to Broadway (1953),[25] in which the songwriters play themselves writing a song for actress Mary Martin's character to perform in a fictional musical.[16][59] Although the song was covered by singer Bing Crosby, "There's Music in You" remained largely obscure for 40 years until it was re-discovered by Cinderella's producers.[54] Despite being selected to musically accompany the film's "happily ever after" finale during Cinderella and the prince's wedding,[62] the original song lacked a bridge and "didn't build properly for Houston's trademark vocal pyrotechnics", according to Zadan,[42] thus it was combined with the bridge of "One Foot, Other Foot" from Rodgers and Hammerstein's musical Allegro (1947).[25][62] Additionally, samples of Cinderella's "Impossible" and the wedding march were interpolated into the melody.[42] Mary described the completed song as "Whitney-fied".[42] Meron believes that these adjustments helped the composition resemble a "Rodgers and Hammerstein song that sounds like a new Whitney Houston record",[25] a sentiment with which Broadway Musicals: A Hundred Year History author David H. Lewis agreed, deeming it "a potential pop hit."[62] Capin considered "There's Music in You" to be a "perfect" addition to the original score because, when combined with "The Sweetest Sounds", it "bookends Cinderella with songs about music" while demonstrating how Cinderella has matured throughout the course of the film.[59] Mary said about the new arrangements, "I'm crazy about what they've done with the music ... They save the original sound while updating it."[42] Rob Marshall choreographed and staged the film's musical numbers,[36][63] which he credits with teaching him how to choreograph dance sequences for motion pictures.[64] Brandy learned to waltz for the role,[37] a task which took her two weeks to perfect.[65] To film the "Impossible" musical sequence, Houston rode on a wooden pulley to simulate the affect that she was flying alongside Cinderella's pumpkin carriage.[42]

Brandy found the recording process "challenging" because the film's songs were different than anything she had recorded before, explaining that she was nervous as her "voice wasn't fully developed, and even if it was fully developed, I wasn't gonna be on Whitney's level", at times struggling to determine "which voice to use."[37] Houston, whom Brandy wanted to impress, would encourage the singer to "Sing from your gut" as opposed to singing from her chest in order to get her to sing louder.[37] Goldberg, who is not primarily known as a singer, also provided her own vocals for the film, by which some of the filmmakers and cast were pleasantly surprised; Goldberg found the process somewhat difficult due to being surrounded by several professional singers, namely Houston, Brandy and Peters.[9] The studio originally planned to release an original soundtrack featuring the film's music.[17] However, this idea was abandoned due to conflicts between Houston and Brandy's respective record labels.[61]

Filming

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was the first of the three versions of the musical to be shot on film.[33] Principal photography began in June 1997 and occurred over a 28-day period,[18][22][66] primarily on stages 22 and 26 at Sony Picture Studios in Culver City, California,[40] which had been the location of MGM Studios during what is now revered as "the golden age of the movie musical."[17] With a then-unprecedented production budget of $12 million, Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella is one of the most expensive television films ever made;[27][67] some media publications dubbed the program "the most expensive two hours ever produced for television."[22][42] In September 1997, Disney Telefilms president Charles Hirschhorn identified the film as the studio's upcoming project on which they had spent the most money.[68] According to A. J. Jacobs of Entertainment Weekly, the film's budget was approximately four-times that of a typical television film.[69] Disney granted the producers this amount because they felt confident that the film would eventually make its budget back once it was released on home video.[42] Zadan agreed that "It's expensive to produce musicals on television. We've only been able to make them because of the home-video component. The show loses money, and the home video [market] makes back the money that you lose."[70]

The film's costumes were designed by Ellen Mirojnick, who aspired towards making them "both funny and stylish" in appearance.[42] In order to give Cinderella's ballgown a "magical look", Mirojnick combined blue and white detailing into the dress, in addition to incorporating a peplum, a design element that had not been used in previous versions of the gown.[71] Cinderella's "glass slippers" were made of shatterproof acrylic as opposed to glass, and only one pair was designed to fit Brandy's feet; the shoe the prince discovers and carries on a pillow in search of its owner was designed to be extremely small in order to give it the appearance of being "incredibly delicate", with Iscove describing it as "too small for any human" foot.[69] In addition to Cinderella herself, Mirojnick costumed all female guests attending the prince's ball in various shades of blue, ranging from aqua to sapphire;[54] Meron believes that Mirojnick's use of color in the characters' costumes distracts from the various skin colors of the film's actors.[42] Meanwhile, the villagers' costumes range in style from "nineteenth-century peasant chic to '40s-esque brocade gowns with exploding collars, bustles, and ruffles."[72] The costume department originally created fake jewelry for Goldberg's character, which consisted of rhinestones for her to wear during the film's ballroom and wedding sequences.[73] However, the actress insisted that the film's queen should wear real jewelry instead and personally contacted jeweler Harry Winston to lend the production millions of dollars worth of jewels,[41] which ultimately included a 70-carat diamond ring and a necklace worth $9 million and $2.5 million, respectively.[73] Winston supplied the set with three armed guards to ensure that the jewelry remained protected at all times and was safely returned at the end of filming.[41][73] The Brooklyn Paper estimates that Goldberg wore approximately $60 million worth of jewelry for the film.[74]

The film's sets were designed by Randy Ser,[17] while art direction was headed by Ed Rubin, who opted to combine a "bright and bold" color palette with "a great deal of subtlety".[42] Iscove identified the film's time period as "nouveau into deco," while also incorporating influences from the work of Gustav Klimt.[42] Prince Christopher's palace was built on the same location as what had been the yellow brick road from the film The Wizard of Oz (1939), thus the palace's courtyard bricks were painted yellow in homage to the classic film.[40] Due to the film's child-friendly message, children and family members of the cast and crew visited the set regularly, including Houston's daughter Bobbi Kristina Brown and husband Bobby Brown.[28] Mary and James often visited the set,[40] as well as Chapin.[17] During a scheduled visit in July, approximately midway through the filming process, Mary and James previewed early footage of the film and met the cast.[17] Hailing the sets as "the most incredible" she had ever seen, Mary described Brandy as "a sweet, wonderful young woman ... I love the fact that millions of children are going to hear her sing 'I can be whatever I want to be.' What better message could we send than that?"[17] Towards the end of filming, the producers realized that they did not have enough money to pay for extras and additional costs, and Disney refused to loan any more money to the production.[41] The producers agreed to finance the remainder of the project using their own money, while Goldberg volunteered to donate the rest of her daily salary to completing the production.[41]

Release

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was heavily promoted as the centerpiece of the newly revived Wonderful World of Disney;[42][69][75] Disney themselves have referred to Cinderella as the "grande dame" of the anthology,[76] while Jefferson Graham of the Chicago Sun-Times touted the film the "crown jewel" of the revival.[77] The same newspaper reported that Cinderella was one of 16 upcoming television films commissioned for the series.[77] One of ABC's promotional advertisements for Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella featured a black-and-white scene from the original 1957 broadcast in which Andrews sings "In My Own Little Corner", which transitions into Brandy singing her more contemporary rendition of the same song, its "funkier orchestration" sounding particularly noticeable opposite Andrews' original.[42] Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella premiered on October 13, 1997 at Mann's Chinese Theatre,[78] which Houston attended with her husband and daughter.[79] The film's impending premiere coincided with the launch of the official Rodgers and Hammerstein website, which streamed segments from the upcoming broadcast via RealVideo from October 27 to November 3, 1997.[51] These segments were again interpolated with excerpts from the 1957 version.[51] A public screening of the film was hosted at the Sony Lincoln Square Theatre in New York on October 27, 1997.[54] Most of the film's cast – Brandy, Houston, Cox, Garber, Desselle and Montalban – was present; Goldberg and Alexander were unable to attend.[54]

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella premiered on November 2, 1997 during The Wonderful World of Disney on ABC, 40 years after the original broadcast.[55] Disney CEO Michael Eisner introduced the program.[40][75] Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was a major ratings success, breaking several television records much like the original did.[44] The telecast aired to over 60 million viewers who watched at least a portion of the film,[14] becoming the most-watched television musical in several years and earning more viewership than 1993's Gypsy.[20] According to the Nielsen ratings, Cinderella averaged a 22.3 rating and 31 share (although it was originally estimated that the program had earned only an 18.8 rating),[14][80] which is believed to have been bolstered by the film's strong appeal towards women and adults between the ages of 18 and 49.[14] Translated, this means that 31 percent of televisions in the United Stated aired the premiere,[20] while 23 million different households tuned in to the broadcast.[14][67] Surprisingly, 70 percent of Cinderella's total viewership that evening consisted of females under the age of 18,[20][81] specifically ages two to 11.[82] The broadcast attracted a particularly high number of younger audience members, including children, teenagers and young adults, in turn making Cinderella the television season's most popular family show.[80]

In addition to being the most-watched program of the evening, Cinderella remained the most-watched program of the entire week, scoring higher ratings than the consistently popular shows ER and Seinfeld.[20] The film became ABC's most-watched Sunday night program in more than 10 years,[83][84] as well as the most-watched program during the network's two-hour 7:00 pm to 9:00 pm time slot in 13–14 years,[14][20][80][85] a record it broke within its first hour of airing.[86] AllMusic biographer Steve Huey attributes the film's high ratings to its "star power and integrated cast".[87] Additionally, the popularity of Cinderella boosted the ratings of ABC's television film Before Women Had Wings, which premiered immediately following the program and consequently earned a rating of 19,[80] retaining much of its viewership from Cinderella's broadcast.[88] ABC's chief researcher Larry Hyams recalled that few "predicted the magnitude of Cinderella's numbers".[89] ABC re-aired the film on February 14, 1999 (Valentine's Day),[27] which was watched by 15 million viewers.[90] Fuse broadcast Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella on November 2, 2017 in honor of the film's 20th anniversary,[58] naming the television special A Night Of Magic: 20th Anniversary of Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella.[91] The network also aired "Cinderella"-themed episodes of Brandy's sitcom Moesha and the sitcom Sister, Sister in commemoration.[58]

Home media

Audiences soon began to demand a quick home video release, which the studio soon began working on.[81] Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella was released on VHS February 10, 1998, which became the highest-selling home video release of any made-for-television film at that time,[83][84] selling one million copies its first week.[70] By February 1999, the video had sold more than two million copies.[27] According to Zadan, musical films struggled to sell well on home video until Cinderella was released.[70] The film was released on DVD on April 2, 2003.[92]

Reception

Critical response

Playbill's Rebecca Paller reviewed the New York screening as "overflowing with star performances, lavish sets" and "lush rainbow-hued costumes", describing its score as "fresher than ever."[54] According to Paller, the screening resembled a Broadway preview more than a film preview since the audience reportedly applauded at the end of every song.[54] Praising its sets, costumes, choreography and script, Paller concluded "everything about the TV play worked", predicting that both young and adult audiences will find the program memorable.[54] Although well-received by the public and audiences, Cinderella premiered to generally lukewarm reviews from most critics,[33][20][93] who were critical of some of its songs, cast and feminist approach,[39][46] at times deeming it inferior to the 1957 and 1965 versions.[94] While the on-screen collaboration of Houston and Brandy was much-anticipated during previews and the weeks preceding the film's premiere, the supporting cast consisting of Peters, Goldberg and Alexander ultimately garnered most of the program's praise.[95] Some purist fans were less impressed with the contemporary arrangements of Rodgers and Hammerstein's original music.[96]

Praising its score and faithfulness to the source material, Eileen Fitzpatrick of Billboard called the film a "sure to please" remake while lauding Brandy's performance, joking that the singer "slips into the Rodgers and Hammerstein Broadway-like score as easily as Cinderella fits into the glass slipper".[30] Fitzpatrick went on to write that the supporting cast lacks "a weak link" entirely, finding it obvious that Houston enjoyed her material and commending the contributions of Peters, Alexander, Goldberg, Garber, Cox and Deselle.[30] New York entertainment critic John Leonard praised the cast extensively, highlighting the performance of Brandy whom the writer said possesses "the grace to transfigure inchoate youth into adult agency" while complimenting the work of Houston, Montalban, Peters, Goldberg and Alexander, the latter of whom the critic identified as a reminder "that he belonged to musical theater before he ever shacked up with Seinfeld's slackers."[97] Leonard also praised the actors' musical performances, particularly Peters' "Falling in Love with Love", but admitted that he prefers the songs used in Disney's 1950 animated adaptation of the fairy tale.[97] In addition to receiving praise for its overall craftsmanship and musical format, critics appreciated the film's color-blind cast.[20][44] Describing the film as "Short, sweet and blindingly brightly colored", TV Guide film critic Maitland McDonagh wrote that Cinderella is "overall ... a pleasant introduction to a classic musical, tweaked to catch the attention of contemporary youngsters."[96] McDonagh observed that the color-blindness of the entire cast spares the film from potentially suffering "disturbing overtones" that otherwise could have resulted from images of an African-American Cinderella being mistreated by her Caucasian stepmother.[96] Despite calling the supporting cast "unusually strong", the critic felt that Brandy and Houston acted too much like their own selves for their contributions to the film to be considered truly compelling performances.[96]

Teresa Talerico, writing for Common Sense Media, praised the film's costumes, sets and musical numbers while lauding the performances of Peters, Goldberg and Houston, but found the choreography "staged and stiff."[98] In a mixed review, The New York Times journalist Caryn James found that the film's multi-racial cast and incorporation of stronger Rodgers and Hammerstein songs help make Cinderella an overall improvement over previous versions of the musical, but admitted that the production still fails to "take that final leap into pure magic. Often charming and sometimes ordinary, this is a cobbled-together 'Cinderella' for the moment, not the ages."[46] While lauding Brandy as "amazingly good ... with the longing of a dreamy adolescent and the musical control of a Broadway trouper" and describing Montalban as her "ideal Prince", James described the film's feminist re-writes as "clumsy" while dismissing Houston as "stiff", accusing the film of wasting her talents.[46] The critic concluded that the broadcast ultimately "sacrifices some of its fairy dust" in favor of emphasizing "inner magic ... self-reliance and love."[46] Similarly, Matthew Gilbert of The Boston Globe complained that despite its "cartoony visual charm" and strong performances, the film lacks "romance, warmth, and a bit of snap in the dance department", failing to become "anything more than a slight TV outing that feels more Nickelodeon than Broadway."[99] Describing the film as "big, gaudy, miles over the top and loads of fun", Variety's Ray Richmond wrote that there can be "so much filling the screen" at times "that you're never quite sure where to look", opining that the entire project "could have been toned down a notch and still carried across plenty of the requisite spunk."[8] While praising Brandy's subtlety, Richmond found Houston's interpretation of the Fairy Godmother to be an overzealous, "frightening caricature, one certain to send the kids scurrying into Mom's lap for reassurance that the good woman will soon go away."[8] Similarly, television critic Ken Tucker, writing for Entertainment Weekly, praised Brandy and Alexander but found that Houston "strikes a wrong note as a sassy, vaguely hostile Fairy Godmother" while dismissing Montalban as "a drearily bland prince" and describing most of the musical numbers as "clunky", predicting that children "will sleep through" the film.[100]

Television critic Howard Rosenberg, in a review for the Los Angeles Times, described Cinderella as a familiar musical in which Brandy's singing is superior to her acting, creating "a tender, fresh Cinderella".[50] Writing that "the magic comes mostly from" Alexander, Peters and Goldberg, Rosenberg was unimpressed with Montalban and Houston, describing them respectively as "pastel as a prince can get (although it's not his fault the character is written as a doofus)" and "not much of a fairy godmother."[50] Rosenberg particularly enjoyed Iscove and Marshall's staging of the ballroom sequence, while describing "the famous shoe-fitting contest" as "delightfully broad nonsense."[50] For Entertainment Weekly, Denise Lanctot praised the film's musical numbers and choreography but found Brandy's performance underwhelming, describing it as "oddly vacuous" and "Barbie-doll blank", writing, "her hoarse voice strains to lyric-soprano heights." However, she called Montalban's prince "perfectly charming" and "The real fairy tale".[6] Similarly, while praising the performances of Houston, Montalban, Alexander and Bernadette Peters, People's Terry Kelleher felt that while Brandy's acting was "fine" her voice was noticeably inferior to Houston's and "lack[ed] the vocal command and emotive power to put over" the film's "soaring, sentimental ballads"".[101] Harlene Ellin of the Chicago Tribune wrote that, despite the production's aesthetics and color-blind casting, the film resembles "the fair maiden who lacks the requisite charm and spark required to snag the handsome prince", concluding that the production "doesn't capture the heart" despite its beauty.[102] While praising the performances of Houston, Peters and Montalban, Ellin wrote that "Cinderella's glass slippers are far too big for Brandy to fill", criticizing her acting while saying that the singer "delivers her lines so timidly and flatly that it's hard to stay focused on the story when Brandy is on the screen", concluding that her co-stars "only makes her weak acting all the more glaring", and causing her to wonder how the film would have turned out had Houston been cast as the lead instead.[102] The Oxford Handbook of The American Musical editor Raymond Knapp believes that Brandy's sitcom experience negatively affected her acting, writing that she often overreacts and delivers lines "as if they were punch lines rather than emotionally generated phrases."[48]

Theater director Timothy Sheader found the production "harsh and unmagical, with very saturated colour."[13] In 2007, theatre historian John Kenrick dismissed the film as "a desecration of Rodgers & Hammerstein's only original TV musical" despite its popularity, advising audiences to only watch the previous versions of the musical.[103]

In its year-end edition, TV Guide ranked the program the best television special of 1997.[20]

Awards and nominations

The film received several accolades.[104] Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was nominated for seven Primetime Emmy Awards,[23][105] including Outstanding Variety, Music or Comedy Special.[84] At the 50th Primetime Emmy Awards in 1998, the film was also nominated for Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program, Outstanding Choreography, Outstanding Costume Design for a Variety or Music Program, Outstanding Directing for a Variety or Music Program, Outstanding Hairstyling for a Miniseries, Movie or a Special, and Outstanding Music Direction, ultimately winning one for Outstanding Art Direction for a Variety or Music Program, which was awarded to Julie Kaye Fanton, Edward L. Rubin and Randy Ser.[106] Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was the 13th most nominated program at that year's ceremony.[67]

The film also won an Art Directors Guild Award for Excellence in Production Design – Awards Show, Variety, Music, or Non-Fiction Program,[107] awarded to Ser.[108] Freedman's teleplay was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Children's Script.[109][110] Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella was nominated for three NAACP Image Awards, including Outstanding Television Movie, Mini-Series or Dramatic Special,[111] while both Brandy and Goldberg were nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Television Movie or Mini-Series.[111] Peters was nominated for a Satellite Award for Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for Television, while Alexander was nominated for Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for Television.[4]

Impact

ABC began discussing the possibility of Disney producing more musical films for the network shortly after Cinderella's premiere,[85] originally commissioning its producers to develop similar musicals to broadcast every November.[112] Bill Carter of The New York Times predicted that the success of the broadcast "will mean more musicals for television, probably as early as" 1998.[81] Similarly, Bert Fink of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization said that the program's ratings will most likely "have a salubrious effect on" the future of television musicals.[14] Hirschhorn interpreted the film's success as an indication that "there is a huge family audience out there for quality programming," expressing interest in eventually "fill[ing] in the ground between feature animated musicals and Broadway".[81] Cinderella's producers immediately began researching other musical projects to adapt for the Wonderful World of Disney, with the network originally hoping to produce at least one similar television special per year,[81] announcing that songwriter Stephen Schwartz had already begun writing a musical adaptation of Pinocchio.[14] In his book The Cambridge Companion to the Musical, author Nicholas Everett identified Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella among important television musicals that "renewed interest in the genre" during the 1990s,[60] with Playbill recognizing it as "the resurgence of televised movie musicals".[113] According to Zadan, Cinderella's success "helped secure a future for musicals in the 'Wonderful World of Disney' slot", whose film company Storyline Entertainment started developing new musicals for the series shortly afterward, including Annie (1999).[27] Although the stage musical Annie had already been adapted for television in 1962, the film was considered to be a critical and commercial failure.[114] Inspired by the success of Cinderella, Zadan and Meron saw remaking the musical as an opportunity to rectify the previous adaptation's errors.[114] They enlisted Cinderella's choreographer Rob Marshall to direct and making the orphans ethnically diverse.[114] According to Vulture.com entertainment critic Matt Zoller Seitz, both productions "stood out for their lush production values, expert control of tone, and ahead-of-the-curve commitment to diverse casting."[115] However, the Los Angeles Times' Brian Lowry observed that few of the series' subsequent projects achieved the ratings that Cinderella had, with viewership for later programming being rather inconsistent.[116]

Following the success of the film, its producers, the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization and Disney began discussing the possibility of adapting the production into a touring stage musical, potentially aiming for 2000 or 2001. However, the idea never came to fruition.[61] Various elements from Freedman's script were used in the 2000 national tour of Cinderella,[117] which is considered by Variety to be the first time the musical was adapted into a "Broadway-style production with a book clearly designed for the stage", including having Cinderella and the prince meet during one of the opening scenes.[118] A stage adaptation of the musical premiered on Broadway in 2013, in which several songs used in the 1997 film are re-used, including "There's Music in You",[119] performed in similar fashion by the Fairy Godmother.[16] Additionally, Montalban has reprised his roles as the prince in both regional and touring productions of the musical, some of which have been based on the 1997 film.[120][121] The Daily Telegraph deemed it "The final of the trio of classic Cinderella remakes".[33] Entertainment Tonight ranked the film the third greatest adaptation of the fairy tale.[122] Highlighting the performances of Montalbán, Peters and Houston are particular highlights, Entertainment Weekly ranked Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella the fourth greatest adaptation of the fairy tale, ahead of both the 1965 (10th) and 1957 (sixth) versions, with author Mary Sollosi calling it one of "the 11 best-known film adaptations of the tale".[49] In 2017, Shondaland.com crowned the film "one of the most inclusive, expensive ... and ultimately beloved TV movies of all time."[21] In 2016, Broadway.com readers voted the Stepmother Peters' 7th best acting role.[123]

Cultural significance

Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella is considered to be a "groundbreaking" film due to its use of a diverse cast and a black actress depicting Cinderella,[1] prior to which Disney's closest example of a black princess was the Muses in Hercules (1997).[21] A BET biographer referred to the production as a "phenomenon" whose cast "broke new ground."[124] Following its success, Disney considered adapting the fairy tale "Sleeping Beauty" into a musical set in Spain featuring Latin music, but the idea never came to fruition.[125] Brandy is considered to be the first African-American to play Cinderella on-screen.[126] Newsweek opined that Brandy's casting disproved the notion that "the idea of a black girl playing the classic Cinderella was unthinkable", calling it "especially significant because for many black women, the 1950 animated Disney Cinderella with her blond hair and blue eyes sent a painful message that only white women could be princesses."[39] Brandy's performance earned her the titles "the first Cinderella of color", "the first black Cinderella" and "the first African-American princess",[37][93][127][128] while Shondaland.com contributor Kendra James dubbed Brandy "Disney's first black princess", crediting her with proving that "Cinderella could have microbraids" and recognizing her as the Cinderella of the 1990s.[21] James concluded, "for a generation of young children of color, 'Cinderella' became an iconic memory of their childhoods, of seeing themselves in a black princess who could lock eyes and fall in love with a Filipino prince. Whitney Houston's persistence had paid off, her dream of a multi-cultural 'Cinderella' production was realized, and its effect was achieved."[21] Like the film, the producers of the stage production have always employed color-bling casting. In 2014, actress Keke Palmer was cast as Cinderella on Broadway, becoming the first black actress to occupy the role in the production. Identifying Brandy as one of her inspirations for the role,[129] Palmer explained, "I feel like the reason I'm able to do this is definitely because Brandy did it on TV".[130]

According to Ruthie Fierberg of Playbill, Brandy's performance "immortalized the role on screen",[131] while Hollywood.com's Jeremy Rodriguez ranked her seventh out of "10 Actresses Who Played Cinderella Like Royalty", praising the scene in which she explains to Prince Christopher that women should be treated with kindness and respect for introducing "a more independent version of the classic character."[132] Fuse TV dubbed Brandy's performance as Cinderella "iconic" and "arguably the most groundbreaking portrayal at time," inspiring the character to become more diverse in the following years.[91] Essence's Deena Campbell credited the singer with "inspiring other young girls to be Black Cinderellas".[133] Media criticism professor Venise Berry found Brandy's casting and performance to be a "wonderful opportunity to reflect the true diversity in our society", writing, "I think that Brandy will help African-American females see there are other possibilities that their lives can blossom into something good, and you don't have to be white for that to happen," in turn making the classic story more accessible "to little black girls" who had believed that ascending into a life of privilege was only possible if you were white.[34] Writing for Nylon, Taylor Bryant called the film both "An Underrated Classic" and "One of the most important moments in [film] history".[94] Applauding the film for providing minorities with "the chance to see themselves depicted as royalty for perhaps the first time", Bryant identified Brandy as a princess for black girls to "fawn" over, which Disney would not revisit until The Princess and the Frog (2009).[94] Similarly, Martha Tesema wrote in an article for Mashable that "seeing Brandy as Cinderella on screen was groundbreaking. I had grown up in a time where future Disney characters like Tiana did not exist and the reason why didn't cross my mind—until this Cinderella. Seeing a princess with box braids like mine and a fairy godmother like Whitney ... gave me and girls who looked like me a glimpse at an early age of why it is necessary to demand representation of all types of people playing all times of roles in films."[31] Ashley Rey, a writer for Bustle, opined that the film "helped show the world that black and brown faces should have just as much of a presence in fairytale land as white faces do."[58]

Martha Tesema, a writer for Mashable, called the film "the best live-action princess remake", writing that it "deserves just as much praise now as it did then."[31] Tesema credits its ethnic diversity with making the film as "enchanting" as it is, continuing that the production "invites you to accept these [characters' races] as just the way they are for a little over an hour and it's a beautiful phenomenon".[31] Furthermore, the writer opined that future live-action remakes should watch Cinderella for reference.[31] In an article for HuffPost, contributor Isabelle Khoo argued that despite the constant remakes that Hollywood produces "no fairy tale adaptation has been more important than Rodgers and Hammerstein's 'Cinderella.'", citing its diverse cast, combating of sexist stereotypes often depicted in other Disney films, and empowering themes that encourage children to make their own dreams come true as opposed to simply "keep on believing" among "three important reasons the 1997 version has maintained relevance today."[134] Khoo observed that fans who had grown up with the film continue to be constantly praised by social media for its diversity, concluding, "With so much talk about the lack of diversity in Hollywood these days, Rodgers and Hammerstein's 'Cinderella' is a shining example of the diversity we need."[134] Similarly, Elle writer R. Eric Thomas crowned Cinderella "One of the Most Important Movies of the '90s". Describing it as "effortlessly, even unintentionally, progressive", Thomas wrote that the film "forecast a world with far more possibility; it's a film made for the future."[72] Crediting the film with establishing both Brandy and Houston as "icons", the writer concluded that Cinderella teaches "about the limitless nature of storytelling. That in stories, there are no constraints; the only limit is your imagination. And once you learn that, you don't unlearn it", representing its theme that nothing is impossible.[72] Mandy Len Catron, author of How to Fall in Love with Anyone: A Memoir in Essays, believes that the film remains "The only truly diverse version of the fairy tale" as of 2017.[135]

See also

- Cinderella, Rodgers and Hammerstein's original 1957 television musical on which the film is based, starring Julie Andrews in the title role

- Cinderella, Disney's 1950 animated musical adaption of the fairy tale

- Cindy, ABC's 1978 re-imagining of the Cinderella fairy tale featuring an all-black cast

References

- 1 2 3 Rohwedder, Kristy (October 12, 2017). "'Cinderella' Star Paolo Montalban Proves Exactly Why This Is The Most Superior Cinderella Movie". Bustle. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella ... yes, that is the movie's full title.

- 1 2 "Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella (1997)". BFI.

Alternative titles – Cinderella

- ↑ "Ellen Mirojnick Biography". Film Reference. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella (also known as Cinderella)

- 1 2 "Peters, Bernadette 1948–". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

Cinderella's stepmother, Cinderella (also known as Rodgers & Hammerstein "Cinderella"), ABC, 1997.

- ↑ "Rob Marshall Biography (1960-)". Film Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

Choreographer and musical staging, "Cinderella" (also known as "Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella")

- 1 2 3 Lanctot, Denise (February 13, 1998). "Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella". Ebony. November 1, 1997. Retrieved August 7, 2018 – via HighBeam Research.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richmond, Ray (October 26, 1997). "Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella". Variety. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

Whitney Houston (one of five executive producers)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Whitney Houston And Brandy Star In TV Movie 'Cinderella'". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. November 3, 1997. pp. 46–47. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved July 31, 2018 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 "Brandy Norwood, Bernadette Peters & More Look Back on Twenty Years Since Cinderella". Broadway World. November 2, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ Hischak, Thomas S. (2007). The Rodgers and Hammerstein Encyclopedia. United States: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313341403 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Viagas, Robert (November 7, 1997). "Playbill Critics Circle: Review TV Cinderella". Playbill. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- 1 2 "Finally, Cinderella is going to the ball". The Independent. November 13, 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gans, Andrew; Lefkowitz, David (November 5, 1997). "TV's Cinderella Turns In Royal Ratings Performance". Playbill. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- 1 2 Byrd, Craig (March 25, 2015). "Curtain Call: Ted Chapin Makes Sure Cinderella Has a Ball". Los Angeles. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Haun, Harry (March 4, 2013). "Playbill on Opening Night: Cinderella; The Very Best Foot Forward". Playbill. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Ring Out The Bells, Sing Out The News: Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella Returns To Television". Rogers and Hammerstein. October 1, 1997. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Stewart, Bhob. "Rodgers & Hammerstein's Cinderella (1997)". AllMovie. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

... this 1997 multicultural version (sometimes referred to as the "rainbow Cinderella")

- 1 2 3 4 Fleming, Michael (May 17, 1994). "Houston to Star in `Cinderella'". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 7, 2018 – via HighBeam Research.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "It's Possible: 60 Million Viewers Go To The Ball With Cinterella". Rogers and Hammerstein. January 1, 1998. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

CINDERELLA scored with the reviews too ... Amidst bravos for the work itself, and adulation for the TV musical form, a quiet, but unmistakable roar of approval also greeted this newest remake for telling its fairy tale with a ""color-blind,"" multi-cultural cast.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 James, Kendra (November 2, 2017). "It's Possible: An Oral History of 1997's "Cinderella"". Shondaland.com. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Fleming, Michael (June 20, 1997). "ABC stages 'Cinderella'". Variety. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Hill, Jim (February 12, 2012). "Remembering Whitney Houston and the 1997 remake of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Whitney & Brandy in Cinderella". Ebony. November 1997. pp. 86–92. Retrieved July 30, 2018 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Purdum, Todd S. (November 2, 1997). "Television; The Slipper Still Fits, Though the Style Is New". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Bego, Mark (2012). Whitney Houston!: The Spectacular Rise and Tragic Fall of the Woman Whose Voice Inspired a Generation. United States: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 116. ISBN 9781620872574 – via Google Books.