Cinderella (1950 film)

| Cinderella | |

|---|---|

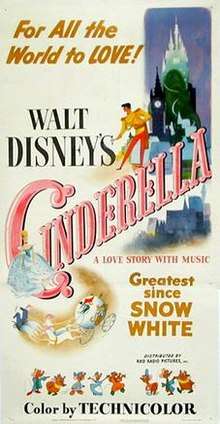

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Written by |

|

| Based on |

Cinderella by Charles Perrault |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Betty Lou Gerson |

| Music by |

Oliver Wallace Paul J. Smith |

| Edited by | Donald Halliday |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date | |

Running time | 75 minutes[4] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.9 million[5] |

| Box office | $263.6 million[5] |

Cinderella is a 1950 American animated musical fantasy film produced by Walt Disney and originally released by RKO Radio Pictures. Based on the fairy tale Cinderella by Charles Perrault, it is the twelfth Disney animated feature film. Directing credits go to Clyde Geronimi, Hamilton Luske, and Wilfred Jackson. Songs were written by Mack David, Jerry Livingston, and Al Hoffman. Songs in the film include "Cinderella", "A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes", "Sing Sweet Nightingale", "The Work Song", "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo", and "So This is Love". It features the voices of Ilene Woods, Eleanor Audley, Verna Felton, Rhoda Williams, James MacDonald, Luis van Rooten, Don Barclay, Mike Douglas, William Phipps, and Lucille Bliss.

At the time, Walt Disney Productions had suffered from losing connections to the European film markets due to the outbreak of World War II, enduring some box office bombs like Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi, all of which would later become more successful with several re-releases in theaters and on home video. At the time, however, the studio was over $4 million in debt and was on the verge of bankruptcy. Walt Disney and his animators turned back to feature film production in 1948 after producing a string of package films with the idea of adapting Charles Perrault's Cendrillon into a motion picture. It is the first Disney film in which all of Disney's Nine Old Men worked together as directing animators. After two years in production, Cinderella was finally released on February 15, 1950. It became the greatest critical and commercial hit for the studio since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and helped reverse the studio's fortunes. It is considered one of the best American animated films ever made, as selected by the American Film Institute. It received three Academy Award nominations, including Best Music, Original Song for "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo". Decades later, it was followed by two direct-to-video sequels—Cinderella II: Dreams Come True and Cinderella III: A Twist in Time—and a 2015 live-action adaptation directed by Kenneth Branagh.[6]

Plot

Cinderella is living a dissatisfying life, having lost both parents at a young age, and being forced to work as a scullery maid in her own château for her cruel stepmother, Lady Tremaine, who is jealous of Cinderella's beauty, and equally cruel stepsisters Drizella and Anastasia. In spite of this, Cinderella is a kind and gentle young woman, and is friends with mice and birds that live in and around the château. Meanwhile, at the royal palace, the King is frustrated that his son, the Prince, still refuses to marry. He and the Grand Duke organize a ball in an effort to find a suitable wife for the Prince, requesting every eligible maiden attend. Upon receiving notice of the ball, Lady Tremaine agrees to let Cinderella go if she finishes her chores and can find a suitable dress to wear.

Cinderella finds a gown that belonged to her mother and decides to refashion it for the ball, but her stepfamily impedes this by giving her extra chores. Cinderella's animal friends, including Jaq and Gus, refashion it for her, completing the design with a necklace and sash discarded by Drizella and Anastasia, respectively. When Cinderella comes downstairs wearing the dress, the stepsisters are upset when they realize Cinderella is wearing their accessories, and tear the dress to shreds before leaving for the ball with their mother. Heartbroken, Cinderella storms out into the garden in tears, where her Fairy Godmother appears before her. Insisting that Cinderella will go to the ball, the Fairy Godmother magically transforms a pumpkin into a carriage, the mice into horses, Cinderella's horse, Major, into a coachman, and dog, Bruno, into a footman, before turning Cinderella's ruined dress into a silver ball gown and her shoes into glass slippers. As Cinderella leaves for the ball, the Fairy Godmother warns her the spell will break at the stroke of midnight.

At the ball, the Prince rejects every girl until he sees Cinderella, who agrees to dance with him, unaware of who he is. The two fall in love and go out for a stroll together in the castle gardens. As they are about to kiss, Cinderella hears the clock start to chime midnight and flees. As she leaves the castle, one of her slippers falls off. The palace guards give chase as Cinderella flees in the coach before the spell breaks on the last stroke of midnight. Cinderella, her pets, and the mice hide in a wooded area as the guards pass.

The Grand Duke informs the King that Cinderella, who remains anonymous, has escaped, and that the Prince wishes to marry her. The lost glass slipper is the only piece of evidence. The King issues a royal proclamation ordering every maiden in the kingdom to try on the slipper for size in an effort to find the girl. After this news reaches Cinderella's household, Lady Tremaine overhears Cinderella humming the waltz played at the ball. Realizing that Cinderella is the mysterious girl, Lady Tremaine locks her in her attic bedroom. Later, the Duke arrives at the château, and Jaq and Gus steal the key from Lady Tremaine's dress pocket and take it up to the attic as Anastasia and Drizella unsuccessfully try on the slipper. Lady Tremaine's cat, Lucifer, ambushes the mice, but Bruno chases him out of the house, allowing the mice to free Cinderella. As the Duke is about to leave, Cinderella appears and asks to try on the slipper. Knowing it will fit, Lady Tremaine trips the footman as he brings the Duke the slipper, causing it to shatter on the floor. Much to her horror, Cinderella presents the Duke with the other slipper, which fits perfectly. The film ends with a now-married Prince and Cinderella at their wedding, sharing a kiss as they leave.

Cast

| Role | Live-Action Reference | Voice | Singer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cinderella | Helene Stanley | Ilene Woods | |

| Lady Tremaine | Eleanor Audley | ||

| Fairy Godmother | Claire Du Brey | Verna Felton | |

| Prince Charming | Jeffrey Stone | William Phipps | Mike Douglas |

| Anastasia Tremaine | Helene Stanley | Lucille Bliss | |

| Drizella Tremaine | Rhoda Williams | ||

| Jaq | None | Jimmy McDonald | |

| Gus | |||

| King | Luis van Rooten | ||

| Grand Duke | |||

| Doorman | Don Barclay | ||

| Lucifer | None | June Foray | |

| Bruno | Pinto Colvig | ||

| Narrator | Betty Lou Gerson | ||

Animators

- Marc Davis, Eric Larson, and Les Clark were the supervising animators of Cinderella

- Frank Thomas was the supervising animator of Lady Tremaine

- Milt Kahl was the supervising animator of Fairy Godmother

- Ollie Johnston was the supervising animator of Drizella Tremaine and Anastasia Tremaine

- Ward Kimball, Wolfgang Reitherman, and John Lounsbery were the supervising animators of Jaq and Gus

- Ward Kimball, John Lounsbery, and Norm Ferguson were the supervising animators of Bruno

- Ward Kimball,John Lounsbery, and Norman Ferguson were the supervising animators of Lucifer

- Milt Kahl and Norman Ferguson were the supervising animators of The King

- Frank Thomas, Milt Kahl, and Norman Ferguson were the supervising animators of The Grand Duke

Production

Story development

In 1922, Walt Disney produced a Laugh-O-Gram cartoon based on "Cinderella", and he had been interested in producing a second version in December 1933 as a Silly Symphony short. Burt Gillett was attached as the director while Frank Churchill was assigned as the composer. A story outline included "white mice and birds" as Cinderella's playmates. To expand the story, storyboard artists suggested visual gags, some of which ended up in the final film.[7] However, the story proved to be too complicated to be condensed into a short so it was suggested as a possible animated feature film as early as 1938 starting with a fourteen-page outline written by Al Perkins.[8][9] Two years later, a second treatment was written by Dana Cofy and Bianca Majolie, in which Cinderella's stepmother was named Florimel de la Pochel; her stepsisters as Wanda and Javotte; her pet mouse Dusty and pet turtle Clarissa; the stepsisters' cat Bon Bob; the Prince's aide Spink, and the stepsisters' dancing instructor Monsieur Carnewal. This version stuck closely to the original fairy tale until Cinderella arrives home late from the second ball. Her stepfamily then imprison Cinderella in a dungeon cellar. When Spink and his troops arrive at the la Pochel residence, Dusty takes the slipper and leads them to free Cinderella.[10]

By September 1943, Disney had assigned Dick Huemer and Joe Grant to begin work on Cinderella as story supervisors and given a preliminary budget of $1 million.[11] However, by 1945, their preliminary story work was halted.[12] During the writing stages of Song of the South, Dalton S. Reymond and Maurice Rapf quarreled, and Rapf was reassigned to work on Cinderella.[13] In his version, Cinderella was written to be a less passive character than Snow White, and more rebellious against her stepfamily. Rapf explained, "My thinking was you can't have somebody who comes in and changes everything for you. You can't be delivered it on a platter. You've got to earn it. So in my version, the Fairy Godmother said, 'It's okay till midnight but from then on it's up to you.' I made her earn it, and what she had to do to achieve it was to rebel against her stepmother and stepsisters, to stop being a slave in her own home. So I had a scene where they're ordering her around and she throws the stuff back at them. She revolts, so they lock her up in the attic. I don't think anyone took (my idea) very seriously."[14]

In spring 1946, Disney held three story meetings, and subsequently received a treatment from Ted Sears, Homer Brightman, and Harry Reeves dated on March 24, 1947. In the treatment, the Prince was introduced earlier in the story reminiscent of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,[15] and there was a hint of the cat-and-mouse conflict. By May 1947, the first rough phase of storyboarding was in the process, and an inventory report that same month suggested a different approach with the story "largely through the animals in the barnyard and their observations of Cinderella's day-to-day activities."[15]

Following the theatrical release of Fun and Fancy Free, Walt Disney Productions' bank debt declined from $4.2 million to $3 million.[16] Around this time, Disney acknowledged the need for sound economic policies, but emphasized to the loaners that slashing production would be suicidal. In order to restore the studio to full financial health, he expressed his desire to return to producing full-length animated films. By then, three animated projects—Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, and Peter Pan—were in development. Disney felt the characters in Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan were too cold, while Cinderella contained elements similar to Snow White, and greenlit the project. Selecting his top-tier animation talent, Ben Sharpsteen was assigned as supervising producer while Hamilton Luske, Wilfred Jackson, and Clyde Geronimi became the sequence directors.[17] Nevertheless, production on Alice resumed so that both animation crews would effectively compete against each other to see which film would finish first.[18]

By early 1948, Cinderella had progressed further than Alice in Wonderland, and was fast-tracked to become the first full-length animated film since Bambi.[15] During a story meeting on January 15, 1948, the cat-and-mouse sequences began to grow into an important element in the film so much that Disney placed veteran story artist Bill Peet in charge of the cat-and-mouse segments.[19]

By the late 1940s, Disney's involvement during production had shrunken noticeably. As he was occupied with trains and the filming of Treasure Island, the directors were left to exercise their own judgment more on details.[20] Although Disney no longer held daily story meetings, the three directors still communicated with him by mailing him memoranda, scripts, Photostats of storyboards, and acetates of soundtrack recordings while he was in England for two and a half months during the summer of 1949. When Disney did not respond, work resumed and then had to be undone when he did.[21] In one instance when Disney returned to the studio on August 29, he reviewed Luske's animation sequences and ordered numerous minor changes, as well as a significant reworking of the film's climax. Production was finished by October 13, 1949.[22]

Casting

Mack David and Jerry Livingston had asked Ilene Woods to sing on several demo recordings of the songs. They had previously known her from her eponymous radio show "The Ilene Woods Show" which was broadcast on ABC. The show featured fifteen minutes of music, in which David and Livingston had their music presented.[23] Two days later, Woods received a telephone call from Disney, with whom she immediately scheduled an interview. Woods recalled in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, "We met and talked for awhile, and he said, 'How would you like to be Cinderella?'," to which she agreed.[24]

For the role of Lucifer, a studio representative asked June Foray if she could provide the voice of a cat. "Well, I could do anything," recalled Foray, "So he hired me as Lucifer the cat in Cinderella".[25]

Animation

Live-action reference

Starting in spring 1948, actors were filmed on large soundstages mouthing to a playback of the dialogue soundtrack.[26] Disney had previously used live-action reference on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, but as part of an effort to keep the production cost down, the footage was used to check the plot, timing, and movement of the characters before animating it.[27] The footage was then edited frame-by-frame onto large Photostat sheets to duplicate, in which the animators found too restrictive as they were not allowed to imagine anything that the live actors did not present since that kind of experimentation might necessitate changes and cost more money. Additionally, the animators were instructed to draw from a certain directorial perspective to avoid difficult shots and angles.[28] Frank Thomas explained, "Anytime you'd think of another way of staging the scene, they'd say: 'We can't get the camera up there'! Well, you could get the animation camera up there! So you had to go with what worked well in live action."[27]

Walt Disney hired actress Helene Stanley to perform the live-action reference for Cinderella, that she before artists began sketching, playing the role of Cinderella in a particular scene,[29] and artists to draw animated frames based on the movements of the actress.[30] She later did the same kind of work for the characters of Princess Aurora in Sleeping Beauty and Anita Radcliff in One Hundred and One Dalmatians.[30] Animators modeled Prince Charming on actor Jeffrey Stone, who also provided some additional voices for the film.[31] Mary Alice O'Connor served as the live-action reference for the Fairy Godmother.[32]

Character animation

By 1950, the Animation Board—which had been established as early as 1940 to help with the management of the animation department—had settled down to nine supervising animators. Although they were still in their thirties, they were jokingly referred by Walt Disney as the "Nine Old Men" after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's denigration of the Supreme Court.[33][34] Including Norman Ferguson, the principal animators included Les Clark, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, Ward Kimball, Eric Larson, John Lounsbery, Frank Thomas, and Wolfgang Reitherman.[35]

Larson was the first to animate the title character whom he envisioned as a sixteen-year-old with braids and a pug nose. Marc Davis later animated Cinderella, in which Larson observed as "more the exotic dame" with a long swanlike neck. Because the final character design was not set, assistant animators were responsible for minimizing the differences.[20] When Disney was asked what was his favorite piece of animation, he answered, "I guess it would have to be where Cinderella gets her ballroom gown", which was animated by Davis.[36]

Milt Kahl was the directing animator of the Fairy Godmother, the King, and the Grand Duke.[37] Originally, Disney intended for the Fairy Godmother to be a tall, regal character as he viewed fairies as tall, motherly figures (as seen in the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio), but Milt Kahl disagreed the characterization. Following the casting of Verna Felton, Kahl managed to convince Disney on his undignified concept of the Fairy Godmother.[38]

Unlike the human characters, the animal characters were animated without live-action reference.[39] During production, none of Kimball's designs for Lucifer had pleased Disney. After visiting Kimball's steam train at his home, Disney saw his calico cat and remarked, "Hey—there's your model for Lucifer".[35] Reitherman animated the sequence in which Jaq and Gus laboriously drag the key up the flight of stairs to Cinderella.[40]

Music

In 1946, story artist and part-time lyricist Larry Morey joined studio music director Charles Walcott to compose the songs. Cinderella would sing three songs: "Sing a Little, Dream a Little" while overloaded with work, "The Mouse Song" as she dressed the mice, and "The Dress My Mother Wore" as she fantasizes about her mother's old wedding dress. In an effort to recycle an unused fantasy sequence from Snow White, the song, "Dancing on a Cloud" was used as Cinderella and the Prince waltz during the ball. After the ball, she would sing "I Lost My Heart at the Ball" and the Prince would sing "The Face That I See in the Night." However, none of their songs were used.[14]

Two years later, Disney turned to Tin Pan Alley songwriters Mack David, Al Hoffman, and Jerry Livingston to compose the songs.[41] The trio had previously written the song "Chi-Baba, Chi-Baba" that Walt heard the radio and decided would work well with the Fairy Godmother sequence. They finished the songs in March 1949.[42]

Oliver Wallace composed the score, but only after the animation was ready for inking, which was incidentally similar to scoring a live-action film. This was a drastic change from the earlier Disney animated features in which the music and action was carefully synchronized in a process known as mickeymousing.[20]

1950 Children's Album

On February 4, 1950, Billboard announced that RCA Records and Disney would release a children's album in conjunction with the theatrical release.[43] The RCA Victor album release sold about 750,000 copies during its first release, and hit number-one on the Billboard pop charts.[44]

| Cinderella | |

|---|---|

| Recording (Children's album) by Ilene Woods With Full Cast | |

| Released | 1950 |

| Label | RCA Victor |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | 3:22 |

| 2. | "The Cinderella Work Song" | 3:29 |

| 3. | "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo (The Magic Song) / So This Is Love" | 3:33 |

| 4. | "A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes" | 3:37 |

Soundtrack

| Cinderella | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | |

| Released | February 4, 1997 |

| Label | Walt Disney |

The soundtrack for Cinderella was released by Walt Disney Records on CD on February 4, 1997, and included a bonus demo.[45] On October 4, 2005, Disney released a special edition of the soundtrack album of Cinderella, for the Platinum Edition DVD release, which includes several demo songs cut from the final film, a new song, and a cover version of "A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes".[46] The soundtrack was released again on October 2, 2012, and consisted of several lost chords and new recordings of them.[47] A Walmart exclusive limited edition "Music Box Set" consisting of the soundtrack without the lost chords or bonus demos, the Song and Story: Cinderella CD and a bonus DVD of Tangled Ever After was released on the same day.[48]

All tracks written by Mack David, Jerry Livingston, Al Hoffman.

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Cinderella (Main Title)" | The Jud Conlon Chorus; Marni Nixon | 2:52 |

| 2. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | Ilene Woods | 4:34 |

| 3. | "A Visitor/Caught in a Trap/Lucifer/Feed the Chickens/Breakfast is Served/Time on Our Hands" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:11 |

| 4. | "The King's Plan" | Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 1:22 |

| 5. | "The Music Lesson/Oh, Sing Sweet Nightingale/Bad Boy Lucifer/A Message from His Majesty" | Rhoda Williams; Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 2:07 |

| 6. | "Little Dressmakers/The Work Song/Scavenger Hunt/A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes/The Dress/My Beads/Escape to the Garden" | James MacDonald; Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 9:24 |

| 7. | "Where Did I Put That Thing?/Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" | Verna Felton; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 4:48 |

| 8. | "Reception at the Palace/So This Is Love" | Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Mike Douglas; Oliver Wallace | 5:45 |

| 9. | "The Stroke of Midnight/Thank You Fairy Godmother" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:05 |

| 10. | "Locked in the Tower/Gus and Jaq to the Rescue/Slipper Fittings/Cinderella's Slipper/Finale" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 7:42 |

| 11. | "I'm In The Middle Of A Muddle" (Demo Recording) |

All tracks written by Mack David, Jerry Livingston, Al Hoffman, except track 12 written and composed by Larry Morey, Charles Wolcott and track 13 written and composed by Jim Brickman, Jack Kugell, Jamie Jones.

| 2005 Special Edition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "Cinderella (Main Title)" | The Jud Conlon Chorus; Marni Nixon | 2:52 |

| 2. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | Ilene Woods | 4:34 |

| 3. | "A Visitor/Caught in a Trap/Lucifer/Feed the Chickens/Breakfast is Served/Time on Our Hands" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:11 |

| 4. | "The King's Plan" | Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 1:22 |

| 5. | "The Music Lesson/Oh, Sing Sweet Nightingale/Bad Boy Lucifer/A Message from His Majesty" | Rhoda Williams; Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 2:07 |

| 6. | "Little Dressmakers/The Work Song/Scavenger Hunt/A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes/The Dress/My Beads/Escape to the Garden" | James MacDonald; Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 9:24 |

| 7. | "Where Did I Put That Thing/Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" | Verna Felton; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 4:48 |

| 8. | "Reception at the Palace/So This Is Love" | Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Mike Douglas; Oliver Wallace | 5:45 |

| 9. | "The Stroke of Midnight/Thank You Fairy Godmother" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:05 |

| 10. | "Locked in the Tower/Gus and Jaq to the Rescue/Slipper Fittings/Cinderella's Slipper/Finale" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 7:42 |

| 11. | "I'm in the Middle of a Muddle (Demo Recording)" | 1:55 | |

| 12. | "Dancing on a Cloud (Demo Recording)" | Ilene Woods; Mike Douglas | 3:49 |

| 13. | "Beautiful" | Jim Brickman; Wayne Brady | 3:43 |

| 14. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | Kimberley Locke | 4:41 |

| Total length: | 56:58 | ||

All tracks written by Mack David, Jerry Livingston, Al Hoffman.

| 2012 Collector's Edition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "Main Title/Cinderella" | The Jud Conlon Chorus; Marni Nixon | 2:52 |

| 2. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | Ilene Woods | 4:34 |

| 3. | "A Visitor/Caught in a Trap/Lucifer/Feed the Chickens/Breakfast is Served/Time on Our Hands" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:11 |

| 4. | "The King's Plan" | Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 1:22 |

| 5. | "The Music Lesson/Oh, Sing Sweet Nightingale/Bad Boy Lucifer/A Message from His Majesty" | Rhoda Williams; Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 2:07 |

| 6. | "Little Dressmakers/The Work Song/Scavenger Hunt/A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes/The Dress/My Beads/Escape to the Garden" | James MacDonald; Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 9:24 |

| 7. | "Where Did I Put That Thing?/Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" | Verna Felton; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 4:48 |

| 8. | "Reception at the Palace/So This Is Love" | Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Mike Douglas; Oliver Wallace | 5:45 |

| 9. | "The Stroke of Midnight/Thank You Fairy Godmother" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:05 |

| 10. | "Locked in the Tower/Gus and Jaq to the Rescue/Slipper Fittings/Cinderella's Slipper/Finale" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 7:42 |

| 11. | "I'm In The Middle of a Muddle" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 12. | "I'm In The Middle of a Muddle" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

| 13. | "I Lost My Heart At the Ball" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 14. | "I Lost My Heart At the Ball" | ||

| 15. | "The Mouse Song" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 16. | "The Mouse Song" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

| 17. | "Sing a Little, Dream A Little" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 18. | "Sing a Little, Dream A Little" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

| 19. | "Dancing On A Cloud" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 20. | "Dancing On A Cloud" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

| 21. | "The Dress My Mother Wore" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 22. | "The Dress My Mother Wore" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

| 23. | "The Face That I See In the Night" (Lost Chords) (Demo) | ||

| 24. | "The Face That I See In the Night" (Lost Chords) (New Recording) | ||

All tracks written by Mack David, Jerry Livingston, Al Hoffman.

| 2012 Limited Edition Music Box Set | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "Main Title/Cinderella" | The Jud Conlon Chorus; Marni Nixon | 2:52 |

| 2. | "A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes" | Ilene Woods | 4:34 |

| 3. | "A Visitor/Caught in a Trap/Lucifer/Feed the Chickens/Breakfast is Served/Time on Our Hands" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:11 |

| 4. | "The King's Plan" | Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 1:22 |

| 5. | "The Music Lesson/Oh, Sing Sweet Nightingale/Bad Boy Lucifer/A Message from His Majesty" | Rhoda Williams; Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 2:07 |

| 6. | "Little Dressmakers/The Work Song/Scavenger Hunt/A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes/The Dress/My Beads/Escape to the Garden" | James MacDonald; Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 9:24 |

| 7. | "Where Did I Put That Thing/Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" | Verna Felton; Paul J. Smith; Oliver Wallace | 4:48 |

| 8. | "Reception at the Palace/So This Is Love" | Ilene Woods; Paul J. Smith; Mike Douglas; Oliver Wallace | 5:45 |

| 9. | "The Stroke of Midnight/Thank You Fairy Godmother" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 2:05 |

| 10. | "Locked in the Tower/Gus and Jaq to the Rescue/Slipper Fittings/Cinderella's Slipper/Finale" | Oliver Wallace; Paul J. Smith | 7:42 |

Release

The film was originally released in theaters on February 15, 1950, in Boston, Massachusetts.[3] Cinderella was re-released in 1957, 1965, 1973, 1981, and 1987.[49] Cinderella also played a limited engagement in select Cinemark Theatres from February 16–18, 2013.[50]

Critical reaction

The film became a critical success garnering the best reception for a Disney animated film since Dumbo. In a personal letter to Walt Disney, director Michael Curtiz hailed the film as the "masterpiece of all pictures you have done." Producer Hal Wallis declared, "If this is not your best, it is very close to the top."[51] Mae Tinee, reviewing for The Chicago Tribune, remarked "The film not only is handsome, with imaginative art and glowing colors to bedeck the old fairy tale, but it also is told in a gentle fashion, without the lurid villains which sometimes give little lots nightmares. It is enhanced by the sudden, piquant touches of humor and the music which appeal to old and young."[52] However, the characterization of Cinderella received a mixed reception. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote, "The beautiful Cinderella has a voluptuous face and form—not to mention an eager disposition—to compare with Al Capp's Daisy Mae." However, criticizing her role and personality, Crowther opined, "As a consequence, the situation in which they are mutually involved have the constraint and immobility of panel-expressed episodes. When Mr. Disney tries to make them behave like human beings, they're banal."[53] Similarly, Variety claimed the film found "more success in projecting the lower animals than in its central character, Cinderella, who is on the colorless, doll-faced side, as is the Prince Charming."[54]

Contemporary reviews have remained positive. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times awarded the film three out of four stars.[55] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader wrote the film "shows Disney at the tail end of his best period, when his backgrounds were still luminous with depth and detail and his incidental characters still had range and bite."[56] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported the film received an approval rating of 97% based on 30 reviews with an average score of 7.7/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "The rich colors, sweet songs, adorable mice and endearing (if suffering) heroine make Cinderella a nostalgically lovely charmer".[57]

Box office

The film was Disney's greatest box office success since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs earning $8 million in gross rentals.[22] By the end of its original run, it was the sixth highest-grossing film in 1950 earning $4.15 million in distributor rentals (the distributor's share of the box office gross).[58] It was the fifth most popular movie at the British box office in 1951.[59] The film is France's sixteenth biggest film of all time in terms of admissions with 13.2 million tickets sold.[60]

The success of Cinderella allowed Disney to carry on producing films throughout the 1950s by which the profits from the film's release, with the additional profits from record sales, music publishing, publications and other merchandise gave Disney the cash flow to finance a slate of productions (animated and live action), establish his own distribution company, enter television production, and begin building Disneyland during the decade, as well as developing the Florida Project, which later known as Walt Disney World.[37]

Cinderella has had a lifetime domestic gross of $95.5 million,[61][62] and a lifetime international gross of $315 million (in 1995 dollars) across its original release and several reissues.[63] Adjusted for inflation, and incorporating subsequent releases, the film has had a lifetime gross of $536,079,700.[64]

Home media

The film was released on VHS and Laserdisc in 1988 as part of the Walt Disney Classics collection. The release had a promotion with a free lithograph reproduction for those who pre-ordered the video before its release date. Disney had initially shipped 4.3 million VHS copies to retailers, but due to strong consumer demand, more than seven million copies were shipped.[65] At the time of its initial home video release, it was the best-selling VHS title until it was overtaken by E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[66] The release was placed into moratorium on April 30, 1989 with seven million VHS copies sold.[67][68]

On October 4, 1995, the film was released on VHS and LaserDisc under the "Masterpiece Collection" lineup. Both editions were accompanied with "The Making of Cinderella" featurette. A Deluxe LaserDisc included the featurette, an illustrated, hardcover book retelling the classic fairy tale with pencil tests and conceptual art from the film, and a reprint of the film's artwork. Disney shipped more than 15 million VHS copies of which 8 million were sold in the first month.[69]

Disney then restored and remastered the movie for its October 4, 2005, release as the sixth installment of the Walt Disney Platinum Editions series. According to Studio Briefing, Disney sold 3.2 million copies in its first week and earned over $64 million in sales. The Platinum Edition was also released on VHS, however the only special feature was the A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes music video by Disney's Circle of Stars[70] The Platinum Edition DVD of the original movie along with its sequels went on moratorium on January 31, 2008. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, a "Royal Edition" of Cinderella was released on DVD on April 4, 2011, to celebrate the UK Royal Wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton. This release had a unique limited edition number on every slipcase and an exclusive art card.[71]

Disney released a Diamond Edition on October 2, 2012, in a 3-disc Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy Combo, a 2-disc Blu-ray/DVD combo and in a 6-disc "Jewelry Box Set" that includes the first film alongside its two sequels. A 1-disc DVD edition was released on November 20, 2012.[72] The Diamond Edition release went back into the Disney Vault on January 31, 2017.

Awards

In 1951, the film received three Academy Award nominations for Best Sound (C. O. Slyfield) lost to All About Eve, Best Music, Scoring of a Musical Picture (Oliver Wallace and Paul J. Smith) lost to Annie Get Your Gun and Best Music, Original Song for "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" (Mack David, Jerry Livingston, and Al Hoffman) lost to Captain Carey, U.S.A..[73] At the 1st Berlin International Film Festival it won the Golden Bear (Music Film) award and the Big Bronze Plate award.[74]

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "10 Top 10"— the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Cinderella was acknowledged as the 9th greatest film in the animation genre.[75][76]

American Film Institute recognition:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Lady Tremaine (Stepmother) – Nominated Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo – Nominated

- A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes – Nominated

- AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – #9 Animated film

Sequels and other media

- A direct-to-video sequel Cinderella II: Dreams Come True was released on February 26, 2002.

- A second direct-to-video sequel Cinderella III: A Twist in Time was released on February 6, 2007.

- Cinderella and the Fairy Godmother have appeared as guests in Disney's House of Mouse.

- Cinderella and the Fairy Godmother appear in the video game Kingdom Hearts and a world based on the film, Castle of Dreams, appears in Kingdom Hearts Birth by Sleep. All the main characters except Gus, Bruno and the King appear.

- A scaled-down stage musical version of the film known as Disney's Cinderella KIDS is frequently performed by schools and children's theaters.[77]

- A live-action adaptation of the film produced by Walt Disney Pictures, directed by Kenneth Branagh was released in 2015; starring Lily James, Richard Madden, Cate Blanchett, and Helena Bonham Carter.

See also

References

- ↑ "Maurice Rapf obituary". The Independent. July 17, 2003. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ↑ Luther, Claudia (April 13, 2003). "Maurice H. Rapf, 88; Blacklisted Screenwriter Had Disney Credits". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Cinderella: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ↑ "CINDERELLA (U)". British Board of Film Classification. March 9, 1950. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- 1 2 "Box Office Information for Cinderella.". The Numbers. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Disney Dates 'Cinderella' For March 2015". deadline.com. June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ↑ The "Cinderella" that Never Was (DVD)

|format=requires|url=(help) (Documentary film). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2005. - ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 397.

- ↑ Barrier 2008, p. 208, 361.

- ↑ Koenig 1997, p. 74.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 397–8.

- ↑ Canemaker, John (2010). Two Guys Named Joe. Disney Editions. p. 165–6. ISBN 978-1423110675.

- ↑ Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. p. 260. ISBN 978-1556526831.

- 1 2 Koenig 1997, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Barrier 1999, p. 398.

- ↑ Barrier 2008, p. 205.

- ↑ Thomas 1994, p. 209.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 459.

- ↑ Barrier 2008, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 Barrier 2008, p. 220.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 399–400.

- 1 2 Barrier 2008, p. 221.

- ↑ Bohn, Marc (2017). Music in Disney's Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1496812148.

- ↑ McLellan, Dennis (July 3, 2010). "Ilene Woods dies at 81; voice of Disney's Cinderella". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ Flores, Terry (July 26, 2017). "June Foray, Voice of 'Bullwinkle Show's' Natasha and Rocky, Dies at 99". Variety. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 399.

- 1 2 Ohmer, Susan (1993). "'That Rags to Riches Stuff': Disney's Cinderella and the Cultural Space of Animation". 5 (2). Film History.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 460.

- ↑ Grant, John (April 30, 1998). The Encyclopedia of Walt Disney's Animated Characters. p. 228. ISBN 978-0786863365.

- 1 2 "Cinderella Character History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31.

- ↑ "Jeffrey Stone, 85, was model for Prince Charming". Big Cartoon Forum. August 24, 2012. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ↑ The Real Fairy Godmother (Blu-Ray)

|format=requires|url=(help) (Bonus feature). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2012. - ↑ Barrier 2008, p. 273-4.

- ↑ Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1981). The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. Abbeville Press. p. 159–60. ISBN 978-0786860708.

- 1 2 Thomas 1994, p. 211.

- ↑ Canemaker 2001, p. 70, 279.

- 1 2 From Rags to Riches: The Making of Cinderella (DVD)

|format=requires|url=(help) (Documentary film). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2005. - ↑ Frank Thomas (May 1973). "Frank Thomas". Walt's People—Volume 10 (Interview). Interviewed by Bob Thomas. Xlibris. p. 97. ISBN 978-1456851507.

- ↑ Canemaker 2001, p. 46.

- ↑ Canemaker 2001, p. 45.

- ↑ Koenig 1997, p. 76.

- ↑ "Music—As Written". Billboard. Vol. 61 no. 10. March 5, 1949. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Disney, RCA Plot Biggest Kidisk Push on "Cinderella" Flick Music". Vol. 62 no. 5. February 4, 1950. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Hollis, Tim; Ehrbar, Greg (2006). Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records. University Press of Mississippi. p. 8. ISBN 978-1578068494.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Mack David, Paul J. Smith, Al Hoffman, Jerry Livingston: Cinderella: An Original Walt Disney Records Soundtrack: Music". amazon.com. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Jim Brickman/Jack Kugell/Jamie Jones, Mack David/Al Hoffman/Jerry Livingston, Larry Morey/Charles Wolcott, Ilene Woods, Jamie Jones, Kimberley Locke, Mike Douglas, Rhoda Williams, Verna Felton, Wayne Brady: Walt Disney's Cinderella - Original Soundtrack: Music". amazon.com. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Various Artists: Cinderella (Disney): Music". amazon.com. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.walmart.com/ip/Cinderella-Music-Box-Set-3-Disc-Box-Set-2-CD-1DVD-Limited-Edition-Walmart-Exclusive/

- ↑ "This Day in History: Disney's Cinderella opens". History. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ↑ Business Wire via The Motley Fool. "Cinemark Announces the Return of Favorite Disney Classic Animated Movies to the Big Screen". DailyFinance.com. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 477.

- ↑ Tinee, Mae (February 24, 1950). "Children Find 'Cinderella' Is a Dream Film". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (February 23, 1950). "Cinderella (1950)". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Review: 'Cinderella'". Variety. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (November 20, 1987). "Cinderella". rogerebert.com. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Cinderella". Chicago Reader. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Cinderella". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Top-Grosses of 1950". Variety. January 3, 1951. p. 58. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Vivien Leigh Actress of the Year". Townsville Daily Bulletin. Qld.: National Library of Australia. December 29, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Top250 Tous Les Temps En France (reprises incluses)". Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Stevenson, Richard (August 5, 1991). "30-Year-Old Film Is a Surprise Hit In Its 4th Re-Release". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ↑ Russell, Candice (November 22, 1991). "A Box-office Draw A French Fairy Tale That Has Been Languishing At Disney Studios For Years, Beauty And The Beast Now Seems Destined To Join The Ranks Of The Very Best Animated Classics". Orlando Sentinel. p. 2. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Disney's Timeless Masterpiece 'Cinderella' Joins The Celebrated Masterpiece Collection On October 4" (Press release). Burbank, California. PRNewswire. May 22, 1995. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "All-Time Box Office: Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Fabrikant, Geraldine (October 17, 1989). "Video Sales Gaining on Rentals". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Harmetz, Aljean (October 27, 1988). "'E.T.,' Box-Office Champ, Sets Video Records". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Stevens, Mary (October 7, 1988). "'Cinderella' Arrives As Belle Of The Vcr Ball". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Cerone, Daniel (March 19, 1991). "The Seven-Year Hitch". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Sandler, Adam (November 26, 1995). "Casper Putting A Scare Into Cinderella". Variety. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Hand-Drawn Cinderella a Huge Hit Again". October 12, 2005. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Cinderella: Royal Edition – The official DVD website". Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ↑ Katz, Josh. "Cinderella: Diamond Edition Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ "The 23rd Academy Awards (1951) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ↑ "1st Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners". berlinale.de.

- ↑ "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Top Ten Animation". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ Disney's Cinderella KIDS

Bibliography

- Barrier, Michael (April 8, 1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802079-0.

- Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520256194.

- Canemaker, John (2001). Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0786864966.

- Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-75747-4.

- Koenig, David (1997). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 978-0964060517.

- Thomas, Bob (April 22, 1994). Walt Disney: An American Original (2nd ed.). Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0786860272.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cinderella (1950 film) |