Christine Todd Whitman

| Christine Todd Whitman | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency | |

|

In office January 31, 2001 – June 27, 2003 | |

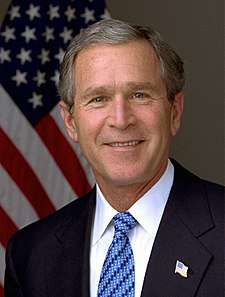

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Carol Browner |

| Succeeded by | Mike Leavitt |

| 50th Governor of New Jersey | |

|

In office January 18, 1994 – January 31, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | James Florio |

| Succeeded by | Donald DiFrancesco |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Christine Temple Todd September 26, 1946 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Education | Wheaton College, Massachusetts (BA) |

Christine Todd Whitman (born September 26, 1946) is an American Republican politician and author who served as the 50th Governor of New Jersey, from 1994 to 2001, and was the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency in the administration of President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2003. She was New Jersey's first and, to date, only female governor.[1] She was the second woman and first Republican woman to defeat an incumbent governor in a general election in the United States. She was also the first Republican woman to be reelected governor.[2]

Early life and family background

Whitman was born Christine Temple Todd, the daughter of Eleanor Prentice Todd (née Schley) and businessman Webster B. Todd, both involved in Republican politics.[3] Both the Todds and the Schleys were wealthy and prominent New Jersey political families.[4] Her mother's family were among the first New Yorkers to move to what became Far Hills, which by the time of Christine's childhood had become a magnet for wealthy, moderate Republicans.[4] Her maternal grandfather, Reeve Schley, was a member of Wolf's Head Society at Yale and the vice president of Chase Bank. He was also a longtime president of the Russian-American Chamber of Commerce.

Christine's father amassed a fortune from working as a building contractor on projects including Rockefeller Center and Radio City Music Hall. Webster used his wealth to donate to Republican politicians, and became an advisor to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Her mother Eleanor served as a Republican national committeewoman and led the New Jersey Federation of Republican Women.[5]

Christine was born in New York City but grew up on the family farm, Pontefract, in Oldwick, New Jersey.[1][4] On the farm, Christine grew up riding horses and fishing.[4] She has three older siblings including her brothers, Webster and Danny.[4][5] Her parents were politically active, taking Christine to her first political convention in 1956 for the renomination of Dwight D. Eisenhower.[4] Her mother's political activity caused a newspaper to speculate that she could be a viable candidate for governor, although Eleanor never chose to run for office.[4] As a child she attended Far Hills Country Day School before being sent to boarding school at Foxcroft in Virginia.[4][6] Christine disliked being so far away from home and after a year transferred to the Chapin School in Manhattan, allowing her to return home on the weekends.[4] After graduating from Wheaton College in 1968, earning a bachelor of arts degree in government, she worked for Nelson Rockefeller's presidential campaign.[1]

At a 1973 inaugural ball for Richard Nixon, Christine had her first date with John R. Whitman, an old friend she had met while a student at Chapin.[4][7] The pair married the next year.[7] Whitman was a private equity investor and a grandson of early 20th-century Governor of New York Charles S. Whitman, thus giving Christine a connection to a well connected New York political family.

Early career

During the Nixon administration, Whitman worked for the Office of Economic Opportunity under Donald Rumsfeld.[1] She conducted a national outreach tour for the Republican National Committee, was deputy director of the New York State Office in Washington, and worked on aging issues for the Nixon campaign and administration. John's job with Citicorp required the family to move to England for three years. When the family returned to the United States, Christine stayed home with the couple's two children, although she did remain active in Somerset County Republican politics.[4]

She was appointed to the board of trustees of Somerset County College, now Raritan Valley Community College. Elected to two terms on the Somerset County Board of Chosen Freeholders, she served as deputy director and director of the board. Among her accomplishments was construction of a new county courthouse.

From 1988 to 1990, she served as president of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities under governor Thomas Kean.[4]

In 1990, Whitman ran for the U.S. Senate against incumbent Bill Bradley, and lost in a close election.[8] She was considered as an underdog against the popular Bradley. During her campaign, Whitman criticized the income tax hike proposed by then governor James Florio. Bradley did not take a stance on the issue.

In 1993, Whitman helped to found the Committee for Responsible Government, an advocacy group espousing moderate positions in the Republican Party. In 1997, the CRG softened its pro-choice position, and renamed itself as the Republican Leadership Council.

Governor of New Jersey

Whitman ran against incumbent James Florio for governor in 1993, and defeated him by one percentage point to become the first female governor in New Jersey history. She was the second woman and first Republican woman to defeat an incumbent governor in a general election, but was unable to gain a majority of the votes, winning by a plurality. Charges of suppression of minority votes were raised during the campaign.[9] Two days after the election, Ed Rollins, Whitman's campaign manager, bragged about having spent $500,000 to suppress the black vote.[4] Whitman denied that Rollin's claim and demanded an apology and a retraction.[10] An investigation into Rollin's claim found no wrongdoing.[4]

Whitman pledged during the campaign that she would lower state taxes by 10% a year for three years. Once in office, she kept the campaign promise, and lowered income taxes.[11] The decline in the tax burden made it likely that the issue of tax revenue shortfall would be addressed later. Jim Saxton, in a report to the federal congress, argued that New Jersey's income tax cuts improved "the well-being of the New Jersey family", and would not lead to an increase in property taxes.[12] Saxton cited Tim Goodspeed's research and a recent paper published by the Manhattan Institute. He admitted that "a few localities raised [property] taxes", as expected by Goodspeed, but both Saxton and Goodspeed counted on the flypaper effect to mitigate any broad or persistent increases. However, the resulting long-term deficit could not be easily reversed, and subsequent governors ran into difficulties with the cumulative revenue losses and interest payments on the debt the state government issued.

In 1995, Whitman was criticized for saying that young African-American males sometimes played a game known as jewels in the crown, which she claimed had as its intent having as many children as possible out of wedlock. Whitman subsequently apologized, and voiced her opposition to attempts by Congressional Republicans to bar unwed teenage mothers from receiving welfare payments.[13]

Also in 1995, the Republican party selected Whitman to deliver the party's State of the Union response.[4] She became the first woman to deliver a State of the Union response by herself; this was also the first State of the Union response given to a live audience.[14]

In 1996, Whitman joined a New Jersey State Police patrol in Camden, New Jersey. During the patrol, the officers stopped a 16-year-old African American male named Sherron Rolax, and frisked him. The police found nothing on him, but Whitman frisked the youth herself, too, while a state trooper photographed the act. In 2000, the image of the smiling governor frisking Rolax was published in newspapers statewide, which drew criticism from civil rights leaders who saw the incident as violation of Rolax's civil rights and Whitman's endorsement of racial profiling – especially since Rolax was not arrested or found to be violating any law. Whitman later told the press that she regretted the incident, and pointed to her efforts in 1999 against the New Jersey State Police force's racial profiling practices. In 2001, Rolax learned about the photograph, and sued Whitman in federal court, claiming that the search was illegal and constituted an invasion of privacy. The appeals court agreed that the act did suggest "an intentional violation" of Rolax's rights, and that he "was detained and used for political purposes by his governor", but upheld the trial court's decision that it was too late to sue.[15][16]

In 1996, Whitman rejected the Advisory Council's recommendation to spend tax money on a needle exchange to reduce incidence of HIV infections.[17]

Whitman was re-elected in 1997, narrowly defeating Jim McGreevey, the mayor of Woodbridge Township, who criticized Whitman's record on property taxes and automobile insurance rates. McGreevey also criticized Whitman for allowing a private sector company to administer the vehicle inspection program. In the 1997 election, the early prediction was that Whitman, as an incumbent, would have an easy win. The result, however, was that Whitman duplicated her 1993 election with only a one-point victory and a plurality of the votes. Murray Sabrin, a college professor who ran as a Libertarian candidate, and finished third with five percent of the vote, received votes mostly from conservative Republicans who might otherwise have voted for Whitman.

In 1997, she repealed the one percentage-point increase to the state sales tax that her predecessor Governor Florio had imposed, reducing the rate from 7% to 6%, instituted education reforms, and removed excise taxes on professional wrestling, which led the World Wrestling Federation to resume events in New Jersey. In 1999, Whitman vetoed a bill that outlawed partial birth abortion. The veto was overridden, but the statute was subsequently declared unconstitutional by the judiciary. In 1999, she made a cameo appearance on the television show Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.[18]

In 1999, Whitman fired Colonel Carl A. Williams, head of the New Jersey State Police, after he was quoted as saying that cocaine and marijuana traffickers were often members of minority groups, while the methamphetamine trade was controlled primarily by white biker gangs.[19]

In 2000, under Whitman's leadership, New Jersey's violation of the federal one-hour air quality standard for ground level ozone dropped to 4 from 45 in 1988. Beach closings reached a record low, and the Natural Resources Defense Council recognized New Jersey for instituting the most comprehensive beach monitoring system in the country. New Jersey implemented a new watershed management program, and became a national leader in opening shellfish beds for harvesting. Whitman agreed to give tax money to owners of one million acres (4,000 km²) or more of open space and farmland in New Jersey.

When Democratic Senator Frank Lautenberg announced that he would not seek re-election in 2000, Whitman considered running,[20] but ultimately decided not to.

EPA Administrator

Whitman was appointed by President George W. Bush as Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency, taking office on January 31, 2001.[21][22]

In the final weeks of the Clinton administration in January 2001, the administration ratified a new drinking water standard of 0.01 mg/L (10 parts per billion, or ppb) of arsenic, to take effect in January 2006. The old drinking water standard of 0.05 mg/L (equal to 50 ppb) arsenic had been in effect since 1942, and the EPA, since the late 1980s, had weighed the pros and cons of lowering the maximum contaminant level (MCL) of arsenic.[23] The incoming Bush administration suspended the midnight regulation, but after months of research, the EPA approved the new 10 ppb arsenic standard to take effect in January 2006 as initially planned.[24]

In 2001, the EPA produced a report detailing the expected effects of global warming in each state in the country. President Bush dismissed the report as the work of "the bureaucracy."[25]

Whitman appeared twice in New York City after the September 11 attacks to inform New Yorkers that the toxins released by the attacks posed no threat to their health.[26] On September 18, the EPA released a report in which Whitman said, "Given the scope of the tragedy from last week, I am glad to reassure the people of New York and Washington, D.C. that their air is safe to breathe and their water is safe to drink." She also said, "The concentrations are such that they don't pose a health hazard...We're going to make sure everybody is safe."[27] A 2003 report by the EPA's Inspector General determined that the assurance was misleading, because the EPA "did not have sufficient data and analyses" to justify it.[28]

A report in July 2003 by the EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response gave extensive documentation supporting many of the inspector general's conclusions.[29] The report further found that the White House had "convinced EPA to add reassuring statements and delete cautionary ones" by having the National Security Council control EPA communications after the September 11 attacks.[30] In December 2007, legal proceedings began on the responsibility of government officials in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Whitman was among the defendants. The plaintiffs alleged that Whitman was at fault for saying that the downtown New York air was safe in the aftermath of the attacks.[31] In April 2008, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit overruled the district court, holding that as EPA administrator, Whitman could not be held liable for assuring the World Trade Center area residents that the air was safe for breathing after the buildings collapsed. The court ruled that Whitman had based her statement on contradictory information from President Bush. The U.S. Department of Justice had argued that holding the agency liable would establish a risky legal precedent because such holding would make public officials afraid of making public statements.

On June 27, 2003, after having several public conflicts with the Bush administration, Whitman resigned.[32][33]

In an interview in 2007, Whitman stated that Vice President Dick Cheney's insistence on easing air pollution controls, not the personal reasons she cited at the time, led to her resignation.[34] At the time, Cheney pushed the EPA to institute a new rule allowing power plants to make major alterations without installing costly new pollution controls.[34] Whitman stepped down in protest against such demand by the White House, she said.[34] She decided that because she did not agree with the rule, she would not be able to defend it if it were to be challenged in a legal action.[34] The federal court eventually overturned the rule on the ground that it violated the Clean Air Act.[34]

In 2016, Whitman apologized for the first time for her declaration a week after 9/11 that the air in lower Manhattan was safe to breathe.[35]

Subsequent career

|

|

Political activism

In early 2005, Whitman released a book entitled It's My Party, Too: Taking Back the Republican Party... And Bringing the Country Together Again in which she criticizes the policies of the George W. Bush administration and its electoral strategy, which she views as divisive.

The defining feature of the conservative viewpoint is a faith in the ability, and a respect for the right, of individuals to make their own decisions – economic, social, and spiritual – about their lives. The true conservative understands that government's track record in respecting individual rights is poor when it dictates individual choices.[37]

The last chapter of that book, entitled "A Time for Radical Moderates", speaks to radical centrists across the political spectrum.[38]

Whitman formed a political action committee called It's My Party Too (IMP-PAC), to assist electoral campaigns of moderate Republicans at all levels of government. IMP-PAC is allied with the Republican Main Street Partnership, The Wish List, the Republican Majority for Choice, Republicans for Choice, Republicans for Environmental Protection and the Log Cabin Republicans. After the 2006 midterm elections, IMP-PAC was merged into RLC-PAC, the Republican Leadership Council's PAC.

Whitman runs the Whitman Strategy Group, an energy lobby organization which claims to be "a governmental relations consulting firm specializing in environmental and energy issues."[39]

In February 2013, Whitman supported legal recognition of same-sex marriage in an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court.[40]

In 2016, Whitman was named the Co-Chair of the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative.[41]

On February 26, 2016 she endorsed John Kasich in his bid seeking the GOP nomination for presidential candidate.[42] She said that Donald Trump was using fascist tactics in his campaign and after Chris Christie's endorsement of Trump said that, in the case of a Trump nomination by the GOP, she would vote for Hillary Clinton.[43][44] Whitman is a member of the ReFormers Caucus of Issue One.[45] The group, which included Bill Bradley and 100 other former elected officials advocated or campaign finance reform.[46]

On May 19, 2012, Whitman was presented with an honorary degree from Washington & Jefferson College.[47]

Corporate activity

Since 2003, Whitman has been on the board of directors of Texas Instruments[48] and United Technologies.[49] Whitman is also co-chair of the CASEnergy Coalition, and in 2007, voiced support for a stronger future role of nuclear power in the United States.[50] Whitman joined the board of the American Security Project in April 2010.[51] By 2015 she served as chairperson of the board of directors.[52] In 2011, Whitman was named to the board of Americans Elect.[53]

Personal life

While governor, Whitman used Pontefract, the family farm on which she was raised, as her primary residence.[4] Whitman had purchased the property in 1991 following the death of her mother.[4]

With her late husband, Whitman has two children: daughter Kate and son Taylor.[4] Kate has followed her mother into politics, including an unsuccessful run for the U.S. House of Representatives and having worked as a Congressional aide.[54][55] In 2007, Kate was named executive director of the Republican Leadership Council, her mother's organization which promotes moderate Republicanism.[56] Whitman has seven grandchildren.[7]

Whitman's hobbies have included mountain biking, playing football, and trapshooting.[4] Whitman also had a Scottish Terrier named Coors (now deceased), who is the mother of former president George W. Bush's dog Barney.[57]

Whitman has been a resident of Tewksbury Township, New Jersey.[58]

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Bradley (incumbent) | 977,810 | 50.44 | ||

| Republican | Christine Todd Whitman | 918,874 | 47.40 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Christine Todd Whitman | 159,765 | 39.96 | ||

| Republican | W. Cary Edwards | 131,587 | 32.91 | ||

| Republican | James Wallwork | 96,034 | 24.02 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Christine Todd Whitman | 1,236,124 | 49.33 | ||

| Democratic | Jim Florio (incumbent) | 1,210,031 | 48.29 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Christine Todd Whitman (incumbent) | 1,133,394 | 46.87 | ||

| Democratic | Jim McGreevey | 1,107,968 | 45.82 | ||

| Libertarian | Murray Sabrin | 114,172 | 4.72 | ||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Governors in New Jersey". governors.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Christine Todd Whitman". The Washington Times. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Pulley, Brett (November 5, 1997). "Woman in the News: Christine Todd Whitman; Just in Time, a Listener". The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Bumiller, Elisabeth (January 24, 1995). "CHRISTINE WHITMAN, SHARPSHOOTER". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- 1 2 Gray, Jerry (June 9, 1993). "Whitman Pursues 'Family Business'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ Bumiller, Elisabeth. "POLITICS: ON THE TRAIL; In Political Quest, Forbes Runs in Shadow of Father", The New York Times, February 11, 1996. Retrieved December 11, 2007. "Christine Todd, Mr. Forbes's childhood friend from the Far Hills Country Day school, would grow up to become Governor Whitman."

- 1 2 3 Slotnik, Daniel E. (July 3, 2015). "John Whitman, Investment Banker and Husband of Governor, Dies at 71". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ King, Wayne. " THE 1990 ELECTIONS: What Went Wrong?; Bradley Says He Sensed Voter Fury But It Was Too Late to Do Anything", The New York Times, November 8, 1990. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

- ↑ Hanson, Christopher. "Insider Cynicism: Ed Rollins Meets the Press" Archived December 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Columbia Journalism Review, January/February 1994. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Gray, Jerry (1993). "Whitman Denies Report by Aide That Campaign Paid Off Blacks". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ↑ Desperately Copying Christe. New York Magazine. October 31, 1994. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ↑ Still Titled: Christine Todd Whitman, the income tax cut, and the property tax issue. "Does Christie = Christine", [Still Titled], November 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Whitman Remark Triggers Another Skirmish On Race She Said Out-of-wedlock Births Were A Sign Of Pride Among Black Males. She Apologized – Fast". Philly.com.

- ↑ "Joni Ernst will be the 16th woman to respond to the State of the Union: Female politicians have been fighting the same sexist attacks for decades". Slate Magazine.

- ↑ Nick Hepp and John P. Martin. "Used by governor, killed by streets", Star Ledger, May 28, 2008.

- ↑ "Sherron Rolax, Appellant V. Christine Todd Whitman; Carl Williams". Lexisone.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Whitman Rejects Panel's Suggestions About Needle Exchange". ndsn.org.

- ↑ "Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: Contact Episode Summary on". Tv.com. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ Fried, Joseph P. (February 17, 2002). "Following Up". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Gov. Whitman moves toward Senate race – April 8, 1999". CNN. 1999-04-08. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ "Christie Todd Whitman – Biography". Environmental Protection Agency. September 21, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ↑ "Environmental Protection Agency, Administrator Christie Todd Whitman". The White House, President George W. Bush. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ↑ "The history of arsenic regulation". Southwest Hydrology: 16. May–June 2002.

- ↑ "EPA announces arsenic standard for drinking water of 10 parts per billion" (Press release). EPA. October 31, 2001.

- ↑ "Compilation of Exhibits for 110th Congress's examination of political interference with climate science" (PDF). House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, U.S. House of Representatives. March 19, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2007.

- ↑ "Video: Health Effects of 9/11 Dust". Google Video. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011.

- ↑ "EPA Response to September 11: Whitman Details Ongoing Agency Efforts to Monitor Disaster Sites, Contribute to Cleanup Efforts". EPA. September 18, 2001.

- ↑ "EPA Report No. 2003-P-00012" (PDF). EPA. August 21, 2008. p. 7.

- ↑ "EPA's Response to the World Trade Center Towers Collapse, A Documentary Basis for Litigation" (PDF). New York Environmental Law and Justice Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2006.

- ↑ Heilprin, John (August 23, 2003). "White House edited EPA's 9/11 reports". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ Portlock, Sarah (December 11, 2007). "Government's Post-9/11 Actions Questioned". The New York Sun. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ↑ Seelye, Katharine Q. "Often Isolated, Whitman Quits As E.P.A. Chief". The New York Times. May 22, 2003.

- ↑ Griscom Little, Amanda. "Muchraker: In her forthcoming memoir, former EPA chief Christine Todd Whitman takes stock of the GOP's "rightward lurch" under Bush" Archived May 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. Salon.com. January 15, 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Becker, Jo; Gellman, Barton. "Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency: Leaving No Tracks" Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.. The Washington Post. Page A01. June 27, 2007.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/10/epa-head-wrong-911-air-safe-new-york-christine-todd-whitman

- ↑ "Christine Todd Whitman: Battle for the GOP Core". Fresh Air. NPR. January 27, 2005. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ↑ Whitman, Christine Todd (2005). It's My Party, Too: The Battle for the Heart of the GOP and the Future of America. The Penguin Press / Penguin Group, p. 73. ISBN 978-1-59420-040-3.

- ↑ Whitman (2005), Chap. 7, pp. 227–44.

- ↑ "Whitman Stragegy Group". Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ Avlon, John. "The Pro-Freedom Republicans Are Coming: 131 Sign Gay-Marriage Brief". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ "Joint Ocean Commission Initiative - About". www.jointoceancommission.org. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Chris Christie endorses Donald Trump for Republican party nomination". NJ.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Whitman compares Trump to Hitler | Moran". NJ.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ "Whitman scorches Christie over Trump, prefers Hillary | Moran". NJ.com. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ↑ https://www.issueone.org/reformers/

- ↑ Salant, Jonathan D. (November 16, 2015). "Ex-N.J. Govs. Tom Kean and Christie Whitman: Big money poisoning politics". NJ.com. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Commencement Ceremony Celebrates Washington & Jefferson College's Class of 2012". Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Corporate Governance: Board of Directors". Texas Instruments. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ↑ "Board of Directors". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Nuclear energy needs to grow". SFGate.

- ↑ "Former New Jersey Governor and EPA Administrator joins the board of the American Security Project". Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Governor Christine Todd Whitman, Chairperson". Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Mak, Tim (December 2, 2011). "Christine Todd Whitman to Jon Huntsman: Run third party – Tim Mak – POLITICO.com". Politico. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Chen, David W. "Former Governor’s Daughter Seeks a Congressional Seat in New Jersey", The New York Times, November 30, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ↑ “UPI's Capital Comment for December 18, 2002”, United Press International, December 18, 2002

- ↑ "On the Road to Reform: An Interview with Kate Whitman" Archived July 18, 2012, at Archive.is, The Moderate Voice, April 16, 2007

- ↑ "Barneys Biography". archives.gov. December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Cohen, Joyce. "HAVENS; Weekender | Tewksbury, N.J.", The New York Times, November 22, 2002. Retrieved March 14, 2011. "The most famous resident is New Jersey's former governor Christine Todd Whitman, now administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, whose family owns a farm there."

Further reading

- Laura Flanders, Bushwomen ( ISBN 1-85984-587-8)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christine Todd Whitman. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christine Todd Whitman |

- New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman, National Governors Association

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- biographical information for Christine Todd Whitman from The Political Graveyard

- Christine Todd Whitman brief bio

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mary Mochary |

Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from New Jersey (Class 2) 1990 |

Succeeded by Dick Zimmer |

| Preceded by Jim Courter |

Republican nominee for Governor of New Jersey 1993, 1997 |

Succeeded by Bret Schundler |

| Preceded by Bob Dole |

Response to the State of the Union address 1995 |

Succeeded by Bob Dole |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by James Florio |

Governor of New Jersey 1994–2001 |

Succeeded by Donald DiFrancesco |

| Preceded by Carol Browner |

Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency 2001–2003 |

Succeeded by Mike Leavitt |