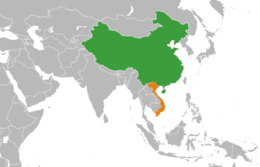

China–Vietnam relations

| |

China |

Vietnam |

|---|---|

The bilateral relations between the People's Republic of China and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Chinese: 中越关系, Vietnamese: Quan hệ Trung Quốc–Việt Nam) have been turbulent, despite their common Sinospheric and socialist background. Centuries of conquest by modern China's imperial predecessor have given Vietnam an entrenched suspicion of Chinese attempts to dominate it.[1][2][3] Though the PRC assisted North Vietnam during the Vietnam War, relations between the two nations soured following Vietnam's reunification in 1975. China and Vietnam fought a prolonged border war from 1979 to 1990, but have since worked to improve their diplomatic and economic ties. However, the two countries remain in dispute over territorial issues in the South China Sea.[4] China and Vietnam share a 1,281-kilometre border. A 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed 84% of Vietnamese were concerned that territorial disputes between China and neighbouring countries could lead to a military conflict.[5]

Early history in imperial period

China and Vietnam have interacted since the Chinese Warring States period and the Vietnamese Thục Dynasty of the 3rd century BC, as noted in the Vietnamese historical record Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư. Between the 1st century BC and 15th century AD, Vietnam was subject to four separate periods of imperial Chinese domination, although it successfully asserted a degree of independence following the Battle of Bạch Đằng in 938 AD.

According to old Vietnamese historical records Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư and Khâm Định Việt Sử Thông Giám Cương Mục, An Dương Vương (Thục Phán) was a prince of the Chinese state of Shu (蜀, which shares the same Chinese character as his surname Thục),[6][7] sent by his father first to explore what are now the southern Chinese provinces of Guangxi and Yunnan and second to move their people to modern-day northern Vietnam during the invasion of the Qin Dynasty.

Some modern Vietnamese believe that Thục Phán came upon the Âu Việt territory (modern-day northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and southern Guangxi province, with its capital in what is today Cao Bằng Province).[8] After assembling an army, he defeated King Hùng Vương XVIII, the last ruler of the Hồng Bàng Dynasty, in 258 BC. He proclaimed himself An Dương Vương ("King An Dương"). He then renamed his newly acquired state from Văn Lang to Âu Lạc and established the new capital at Phong Khê in the present-day Phú Thọ town in northern Vietnam, where he tried to build Cổ Loa Citadel), the spiral fortress approximately ten miles north of that new capital.

Han Chinese migration into Vietnam dated back to the era of the 2nd century BC when Qin Shi Huang first placed northern Vietnam under Chinese rule, Chinese soldiers and fugitives from Central China migrated en masse into northern Vietnam from this time onwards, and introduced Chinese influences into Vietnamese culture.[9][10] The Chinese military leader Zhao Tuo founded the Triệu dynasty which ruled Nanyue in southern China and northern Vietnam. The Qin Governor of Canton advised Zhao to found his own independent Kingdom since the area was remote and there were many Chinese settlers in the area.[11] The Chinese prefect of Jiaozhi Shi Xie ruled Vietnam as an autonomous warlord and was posthumously deified by later Vietnamese Emperors. Shi Xie was the leader of the elite ruling class of Han Chinese families who immigrated to Vietnam and played a major role in developing Vietnam's culture.[12]

After Vietnam regained independence, a serious war between China and Vietnam occurred, which the Vietnamese, at its peak, invaded China once during the Lý–Song War which the Lý Army raided into China and even occupied what would be Guangxi and Guangdong in modern days' China. This would be the major factor for the later conflict between China and Vietnam. The Ming Dynasty invaded Vietnam and occupied Vietnam in what would be the Fourth Millennium, only be defeated by the army of rebel leader Lê Lợi, who later founded the Later Lê Dynasty in Vietnam. The Qing Dynasty had also attempted to conquer Vietnam but was defeated by Emperor Quang Trung at 1789. Quang Trung had also attempted to conquer China, but he died before it was proposed.

In 1884, during the time of Vietnam's Nguyễn Dynasty, Qing China and France fought a war which ended in a Chinese defeat. The resulting Treaty of Tientsin recognized French dominance over Vietnam and Indochina, spelling the end of formal Chinese influence on Vietnam, and the beginning of Vietnam's French colonial period.

Both China and Vietnam faced invasion and occupation by Imperial Japan during World War II, while Vietnam languished under the rule of the pro-Nazi Vichy French. In the Chinese provinces of Guangxi and Guangdong, Vietnamese revolutionaries led by Phan Bội Châu had arranged alliances with the Chinese nationalist Kuomintang prior to the war by marrying Vietnamese women to Chinese officers. Their children were at an advantage, since they could speak both languages, and they worked as agents for the revolutionaries, spreading revolutionary ideologies across borders. This intermarriage between Chinese and Vietnamese was viewed with alarm by the French. In addition, Chinese merchants married Vietnamese women, and provided funds and help for revolutionary agents.[13]

Late in the war, with Japan and Germany nearing defeat, the US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, privately decided that the French should not reacquire their colonial property of French Indochina after the war was over. Roosevelt offered the Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek the entirety of Indochina to be put under Chinese rule. Reportedly, Chiang Kai-shek replied: "Under no circumstances!".[14] In August 1943, China broke diplomatic relations with the Vichy France regime, with the Central Daily News announcing diplomatic relations were to be solely between the Chinese and Vietnamese people, with no French intermediary. China had planned to widely spread the propaganda of the Atlantic Charter and Roosevelt's statement on Vietnamese self-determination, in order to undermine French authority in Indochina.[15]

However, with the death of Roosevelt, his successor Harry S. Truman switched his position on Vietnamese independence in order to gain the support of Free French Forces in Europe.

According to a 2018 study in the Journal of Conflict Resolution covering Vietnam-China relations from 1365 to 1841, the relations could be characterized as a "hierarchic tributary system".[16] The study found that "the Vietnamese court explicitly recognized its unequal status in its relations with China through a number of institutions and norms. Vietnamese rulers also displayed very little military attention to their relations with China. Rather, Vietnamese leaders were clearly more concerned with quelling chronic domestic instability and managing relations with kingdoms to their south and west."[16]

Cold War

After the war, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han were sent by Chiang Kai-shek to Indochina north of the 16th parallel, with the aim of accepting the surrender of Japanese occupying forces. These troops remained in Indochina until 1946.[17] The Chinese used the VNQDD, the Vietnamese branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in Indochina and put pressure on their opponents.[18] Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war to force them to negotiate with the Vietminh leader Ho Chi Minh. In February 1946, Chiang Kai-shek forced the French colonists to surrender all of their concessions in China and renounce their extraterritorial privileges, in exchange for withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to reoccupy the region.[19][20][21][22]

Vietnam War

Along with the Soviet Union, Communist China was an important strategic ally of North Vietnam during the Vietnam War. The Chinese Communist Party provided, arms, military training and essential supplies to help the Communist North defeat Capitalist South Vietnam and its ally, the United States, between 1954 and 1975. [23] During 1964 to 1969, the PRC reportedly sent over 300,000 troops, mostly in anti-aircraft divisions to combat in Vietnam. [24] However, the Vietnamese Communists remained suspicious of China's perceived attempts to increase its influence over Vietnam.[1]

Vietnam was an ideological battleground of the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, Chinese Premier Deng Xiaoping secretly promised the North Vietnamese 1 billion yuan in military and economic aid, on the condition that they refused all Soviet aid.

During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese and the Chinese had agreed to defer tackling their territorial issues until South Vietnam was defeated. These issues included the lack of delineation of Vietnam's territorial waters in the Gulf of Tonkin, and the question of sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.[1] During the 1950s, half of the Paracels were controlled by China and half by South Vietnam. In 1958, North Vietnam accepted China's claim to the Paracels, relinquishing its own claim;[25] one year earlier, China had ceded White Dragon Tail Island to North Vietnam.[26] The potential of offshore oil deposits in the Gulf of Tonkin heightened tensions between China and South Vietnam. In 1973, with the Vietnam War drawing to a close, North Vietnam announced its intention to allow foreign companies to explore oil deposits in disputed waters. In January 1974, a clash between Chinese and South Vietnamese forces resulted in China taking complete control of the Paracels.[1] After its absorption of South Vietnam in 1975, North Vietnam took over the South Vietnamese-controlled portions of the Spratly Islands.[1] The unified Vietnam then canceled its earlier renunciation of its claim to the Paracels, while both China and Vietnam claim control over all the Spratlys, while both controlling portions of the island group.[25]

Sino-Vietnamese conflicts 1979–90

In the wake of the Vietnam War, the Cambodian–Vietnamese War provoked tensions with China, which had allied itself with the Democratic Kampuchea.[1][27] This, and Vietnam's close ties to the Soviet Union, made China consider it a threat to its regional sphere of influence.[27][28] Tensions were furthermore heightened in the 1970s by the Vietnamese government's oppression of the Hoa minority, which consists of Vietnamese of Chinese ethnicity.[1][27][28] By 1978, China ended its aid to Vietnam, which had signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union, establishing extensive commercial and military ties.[1][27]

On February 17, 1979, the Chinese People's Liberation Army crossed the Vietnamese border, withdrawing on March 5 after a two-week campaign which devastated northern Vietnam and briefly threatened the Vietnamese capital, Hanoi.[1][28] Both sides suffered relatively heavy losses with thousands of casualties. Subsequent peace talks broke down in December 1979, and both China and Vietnam began a major build-up of forces along the border. Vietnam fortified its border towns and districts and stationed as many as 600,000 troops; China stationed approximately 400,000 troops on its side of the border.[28] Sporadic fighting on the border occurred throughout the 1980s, and China threatened to launch another attack to force Vietnam's exit from Cambodia.[1][28]

1990-present

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and Vietnam's exit from Cambodia in 1990, Sino-Vietnamese ties began improving. Both nations planned the normalization of their relations in a secret summit in Chengdu in September 1990, and officially normalized ties in November 1991.[27] Since 1991, the leaders and high-ranking officials of both nations have exchanged visits. China and Vietnam both recognized and supported the post-1991 government of Cambodia, and supported each other's bid to join the World Trade Organization (WTO).[27] In 1999, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Le Kha Phieu, visited Beijing, where he met General Secretary of the Communist Party of China Jiang Zemin and announced a joint "16 Word Guideline" for improved bilateral relations; a Joint Statement for Comprehensive Cooperation was issued in 2000.[27] In 2000, Vietnam and China successfully resolved longstanding disputes over their land border and maritime rights in the Gulf of Tonkin.[23][27] A joint agreement between China and ASEAN in 2002 marked out a process of peaceful resolution and guarantees against armed conflict.[27] In 2002, Jiang Zemin made an official visit to Vietnam, where numerous agreements were signed to expand trade and cooperation and resolve outstanding disputes.[23]

Commercial ties

After both sides resumed trade links in 1991, growth in annual bilateral trade increased from only US$32 million in 1991 to almost USD $7.2 billion in 2004.[29] By 2011, the trade volume had reached USD $25 billion.[30] It is predicted that China will become Vietnam's largest single trading partner, overtaking the United States, by 2030.[31] China's transformation into a major economic power in the 21st century has led to an increase of foreign investments in the bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[32][33]

Vietnam's exports to China include crude oil, coal, coffee and food, while China exports pharmaceuticals, machinery, petroleum, fertilizers and automobile parts to Vietnam. China has become Vietnam's second-largest trading partner and the largest source of imports.[23][29] Both nations are working to establish an "economic corridor" from China's Yunnan province to Vietnam's northern provinces and cities, and similar economic zones linking China's Guangxi province with Vietnam's Lạng Sơn and Quang Ninh provinces, and the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong.[29] Air and sea links as well as a railway line have been opened between the two countries, along with national-level seaports in the frontier provinces and regions of the two countries.[23] Joint ventures have furthermore been launched, such as the Thai Nguyen Steel Complex, which produces hundreds of thousands of tonnes of steel products.[29]

Chinese investments in Vietnam have been rising since 2015, reaching USD 2.17 billion in 2017.[34]

In 2018, protesters went on the streets in Vietnam against government plans to open new special economic zones, including one in Quang Ninh, near the Chinese border, that would allow 99-year land leases, citing concerns about Chinese dominance.[35][36]

Rekindled tensions over maritime territory

In June 2011, Vietnam announced that its military would conduct new exercises in the South China Sea. China had previously voiced its disagreement over Vietnamese oil exploration in the area, stating that the Spratly Islands and the surrounding waters were its sovereign territory.[37] Defense of the South China Sea was cited as one of the possible missions of the first Chinese aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, which entered service in September 2012.[38]

In October 2011, Nguyễn Phú Trọng, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, made an official visit to China at the invitation of General Secretary of the Communist Party of China Hu Jintao, with the aim of improving bilateral relations in the wake of the border disputes.[30] However, on 21 June 2012, Vietnam passed a law entitled the "Law on the Sea", which placed both the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands under Vietnamese jurisdiction, prompting China to label the move as "illegal and invalid".[39] Simultaneously, China passed a law establishing the prefecture of Sansha City, which encompassed the Xisha (Paracel), Zhongsha, and Nansha (Spratly) Islands and the surrounding waters.[40] Vietnam proceeded to strongly oppose the measure and reaffirmed its sovereignty over the islands. Other countries surrounding the South China Sea have claims to the two island chains, including Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines; nonetheless, the conflict remains predominantly between Vietnam and China.[39][41]

In May 2013 Vietnam accused the PRC of hitting one of its fishing boats,[42] while in May 2014 Vietnam accused China of ramming and sinking a fishing boat.[43]

In June 2014 China declared there would be no military conflict with Vietnam as the two were sparring over an oil rig in disputed territory in the South China Sea. China at the time had 71 ships in the disputed area while Vietnam had 61.[44]

In 2017, Beijing warned Hanoi that it would attack Vietnamese bases in the Spratly Islands if gas drilling continued in the area. Hanoi then ordered Spain's Repsol, whose subsidiary was conducting the drilling, to stop drilling.[45][46]

According to the Council on Foreign Relations the risk of a military confrontation between China and Vietnam is rising.[47]

Diplomatic missions

See also

- List of ambassadors of China to Vietnam

- List of ambassadors of Vietnam to China

- History of China

- History of Vietnam

- Sinicization

- Sinophobia

- Sino-Vietnamese Wars (disambiguation)

- Poland–Russia relations, sometimes regarded as the closest version of Sino–Vietnamese relations

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Vietnam - China". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ↑ Forbes, Andrew. "Why Vietnam Loves and Hates China". Asia Times. 26 April 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "China: The Country to the North". Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David (2012). Vietnam Past and Present: The North. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006DCCM9Q.

- ↑ "Q&A: South China Sea dispute". BBC. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Chapter 4: How Asians View Each Other". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Taylor, K.W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780520074170. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Far-Eastern Prehistory Association (1990). Asian Perspectives. University Press of Hawaii. ISSN 0066-8435. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Chapuis, O. (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780313296222. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Long Le (February 8, 2008). "Chinese Colonial Diasporas (207 B.C.-939 A.D.)". University of Houston Bauer The Global Viet. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ↑ Long Le (January 30, 2008). "Colonial Diasporas & Traditional Vietnamese Society". University of Houston Bauer The Global Viet. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, K.W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780520074170. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Taylor, K.W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780520074170. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Christopher E. Goscha (1999). Thailand and the Southeast Asian networks of the Vietnamese revolution, 1885-1954. Psychology Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-7007-0622-4.

- ↑ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (1985). The march of folly: from Troy to Vietnam. Random House, Inc. p. 235. ISBN 0-345-30823-9.

- ↑ Liu, Xiaoyuan (2010). "Recast China's Role in Vietnam". Recast All Under Heaven: Revolution, War, Diplomacy, and Frontier China in the 20th Century. Continuum. pp. 66, 69, 74, 78.

- 1 2 "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841". Journal of Conflict Resolution. doi:10.1177/0022002718772345.

- ↑ Larry H. Addington (2000). America's war in Vietnam: a short narrative history. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-253-21360-6.

- ↑ Peter Neville (2007). Britain in Vietnam: prelude to disaster, 1945-6. Psychology Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-415-35848-5.

- ↑ Van Nguyen Duong (2008). The tragedy of the Vietnam War: a South Vietnamese officer's analysis. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 0-7864-3285-3.

- ↑ Stein Tønnesson (2010). Vietnam 1946: how the war began. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-520-25602-6.

- ↑ Elizabeth Jane Errington (1990). The Vietnam War as history: edited by Elizabeth Jane Errington and B.J.C. McKercher. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 0-275-93560-4.

- ↑ "The Vietnam War: Seeds of Conflict 1945–1960". The History Place. 1999. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "China-Vietnam Bilateral Relations". Sina.com. 28 August 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ↑ "CHINA ADMITS COMBAT IN VIETNAM WAR". Washington Post. 17 May 1989. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- 1 2 Cole, Bernard D (2012). The Great Wall at Sea: China's Navy in the Twenty-First Century (2 ed.). Naval Institute Press. p. 27.

- ↑ Frivel, M. Taylor. "Offshore Island Disputes". Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. pp. 267–299.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Womack, Brantly (2006). China and Vietnam: Politics of Asymmetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 0-521-85320-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Chinese invasion of Vietnam". Global Security.org. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "China, Vietnam find love". Asia Times. 21 July 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- 1 2 "China, Vietnam Seek Ways to Improve Bilateral Relations". China Radio International. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "China to become Viet Nam's largest trading partner". Viet Nam News. 29 March 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Quinlan, Joe (November 13, 2007). "Insight: China's capital targets Asia's bamboo network". Financial Times.

- ↑ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ↑ Nguyen T.H.K.; et al. (May 26, 2018). "The "same bed, different dreams" of Vietnam and China: how (mis)trust could make or break it". Thanh Tay University. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "Vietnam police halt protests against new economic zones".

- ↑ "Vietnamese see special economic zones as assault from China".

- ↑ AP via Chron.com. "Vietnam Plans Live-fire Drill after China Dispute". 10 June 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "China’s Navy passes first aircraft-carrier into service". Voice of Russia. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- 1 2 "Vietnam slams 'absurd' China protest over islands". gulfnews.com. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "China announces creating Sansha city". ChinaBeijing.org. 24 June 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "Vietnam breaks up anti-China protests". BBC. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ "Vietnam Accuses Chinese Vessel of Hitting Its Fishing Boat". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "Hanoi Says Chinese Ships Ram, Sink Vietnamese Fishing Boat". Vietnam Tribune. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "China rebuts Vietnam charge of it forcing territorial dispute". China News. Net. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ https://www.cnbc.com/2017/07/23/china-threatens-vietnam-over-south-china-sea-drilling.html

- ↑ South China Sea: Vietnam halts drilling after 'China threats' - BBC News

- ↑ A China-Vietnam Military Clash | Council on Foreign Relations

Bibliography

- Andaya, Barbara Watson. (2006). The Flaming Womb: Repositioning Women in Early Modern Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824829557. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Cardenal, Juan Pablo; Araújo, Heriberto (2011). La silenciosa conquista china (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 230–232, 258ff.

- Cœdès, George. (1966). The Making of South East Asia (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0520050614. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Dardess, John W. (2012). Ming China, 1368-1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442204907. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Hall, Kenneth R., ed. (2008). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400-1800. Volume 1 of Comparative urban studies. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739128353. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Le Hong Hiep (December 2013). "Vietnam's Hedging Strategy against China since Normalization". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 35 (3): 333–368.

- Taylor, K. W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521875862. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Taylor, Keith Weller. (1983). The Birth of Vietnam (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0520074173. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry. (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. ISBN 1438422369. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Contributor: Far-Eastern Prehistory Association Asian Perspectives, Volume 28, Issue 1. (1990) University Press of Hawaii. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

External links

- Chinese embassy in Vietnam (in Chinese)

- Vietnamese embassy in Beijing, China (in Vietnamese) (in Chinese)

.svg.png)