Lý–Song War

| Lý–Song War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

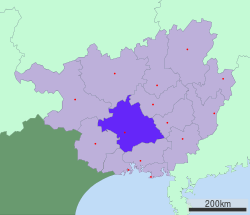

Map of the two dynasties, Song Dynasty in Orange, Lý Dynasty in Purple | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Song dynasty | Đại Việt under the Lý dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Guo Kui (郭逵) Zhao Xie (趙禼) Zhang Shoujie (張守節) † Su Jian (蘇緘) † |

Lý Thường Kiệt Nùng Tôn Đản Thân Cảnh Phúc Lưu Ưng Ký (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Battle of Yongzhou: More than 2800 regular troops[2] Song Counteroffensive: 300,000 regular troops and people[3] |

Invasion of Guangxi: 80,000–100,000 troops[4] During Song Counteroffensive: 60,000 (estimate)[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 250,000–400,000 troops and civilians (including massacre of Yongzhou): More than half of Song troops died from disease during the counteroffensive against Lý[6][7] | 20,000 in battle of Guangxi, casualties during Song Counteroffensive unknown | ||||||

The Lý–Song War was a significant war fought between the Lý dynasty of Đại Việt and the Song dynasty of China between 1075 and 1077. The war began in 1075 when the Lý emperor ordered a preemptive invasion of the Song dynasty using more than 100,000 soldiers, where Đại Việt's forces defeated the Song army and razed the city of Yongzhou (modern day Nanning) to the ground after a forty-two day siege. In response, in 1076 the Song led an army of over 300,000 to invade Đại Việt and by 1077 nearly reached Thăng Long, the capital of Đại Việt, before being halted by general Lý Thường Kiệt at the Nhu Nguyệt River in modern Bắc Ninh Province. After a long battle at the river with high casualties on both sides, Lý Thường Kiệt offered peace to the Song, and the Song commander Guo Kui agreed to withdraw his troops, ending the war.

Background

Tension and border hostilities were already high in the years prior to the war; in the 1050s, Nùng Trí Cao, the head of the local Nùng people in Quảng Nguyên (now Cao Bằng Province) attempted to fight for independence and establish a frontier state for his people, but his rebellion was crushed by Song general Di Qing (1008–1061).[8] While the Lý court did not intervene in the matter, the threat of Song expansion was always on the horizon due to increasing numbers of Han Chinese settlers, such as the soldiers from Di Qing's division and those north of the Yangzi River settled in areas that the Lý relied upon for the extraction of natural resources.[9][10]

In 1075, Wang Anshi, the chancellor of the Song dynasty, told Emperor Shenzong (r. 1067–1085) that Đại Việt was being destroyed by Champa, with less than ten thousand soldiers surviving, so hence it would be a good occasion to annex Đại Việt. The Song emperor then mobilized his troops and passed a decree to forbid all the provinces of Song to trade with Đại Việt; this prompted the Lý court under Emperor Lý Nhân Tông (r. 1072–1127) to authorize a preemptive invasion of Guangxi in the Song dynasty. Lý Nhân Tông then sent general Lý Thường Kiệt and Nùng Tông Đán, a kinsman of the Nùng rebel Nùng Trí Cao, to lead more than a hundred thousand soldiers to invade the Chinese province of Guangxi.[11]

The War

In the autumn of 1075, Nùng Tông Đán advanced into Song territory in Guangxi while a naval fleet commanded by Lý Thường Kiệt captured Qinzhou and Lianzhou prefectures.[12] Lý Thường Kiệt calmed the apprehensions of the local Chinese populace, claiming that he was simply apprehending a rebel who took refuge in China and that the local Song authorities had refused to cooperate in detaining him.[13] In the early spring of 1076, Thường Kiệt and Nùng Tông Đán defeated the Song militia of Yongzhou,[13] and during a battle at Kunlun Pass, their forces beheaded the Governor-General of Guangnan West Circuit, Zhang Shoujie (d. 1076).[13] Afterwards, the Lý forces then marched towards the city of Yongzhou, where they were temporarily held up by a fierce resistance led by the Yongzhou governor Su Jian, who with three thousand soldiers prevented the city from falling for forty-two days.[14] After the forty-two-day siege, on March 1, 1076, Yongzhou was finally breached and then razed to the ground, as Lý forces massacred 58,000 people within the city.[15] Prior to the massacre, after the city was lost, governor Su Jian and thirty-six members of his family in the city committed suicide, with Su Jian stating "I won't die at the hands of those thieves."[16] Several sources estimate that the total number of people killed by Lý troops during this campaign totaled 100,000.[6][17][13] When Song forces attempted to challenge Lý's forces, the latter retreated, with their spoils of war and thousands of prisoners.[13]

Lý Thường Kiệt had fought a war with the Chams in 1069, and in 1076, the Song called upon their vassal states the Khmer Empire and Champa to go to war again against the Lý. At the same time, the Song commander Guo Kui (1022–1088) led the combined Song force of approximately 300,000 men against Lý,[3] who were at the time simultaneously defending against incursions from the Khmer Empire and Champa.[13] The Song quickly regained Quảng Nguyên prefecture and in the process captured the resistance leader Lưu Ký, the chieftain of Quảng Nguyên that had attacked Yongzhou in 1075.[13] By 1077, the Song had destroyed two other Vietnamese armies and marched towards their capital at Thăng Long (modern Hanoi).[13] Song forces were halted at the Nhu Nguyệt River (in modern Bắc Ninh Province), where Lý Thường Kiệt had built a defense system by placing spikes under the Như Nguyệt riverbed before tricking Song troops into the death trap, killing more than 1,000 Chinese soldiers and sailors.[13] In avoiding this strong defense system, the commander of the Song army, Guo Kui decided to change the army's direction towards the nearby region of Phú Lương, where they then defeated Lý Thường Kiệt's forces in a major battle. As the Song forces took the offensive, while the Lý Dynasty had to strenuously hold on to their costly defensive front, Lý Thường Kiệt tried to boost the morale of his soldiers by citing a poem before his army named "Nam quốc sơn hà".[17] However, Song forces eventually broke through his defense line and their cavalry advanced to within several kilometers of the capital city.[18] The Vietnamese counterattacked and pushed Song forces back across the river while their coastal defenses distracted the Song navy. Lý Thường Kiệt also launched an offensive, but lost two Lý princes in the fighting at Kháo Túc River.[18] According to Chinese sources, "tropical climate and rampant disease" severely weakened Song's military forces while the Lý court feared the result of a prolonged war so close to the capital.[18][15]

As a result of mounting casualties on both sides, Thường Kiệt made peace overtures to the Song; the Song commander Guo Kui agreed to withdraw his troops since they had lost 400,000 men,[6] but kept five disputed regions of Quảng Nguyên (renamed Shun'anzhou or Thuận Châu), Tư Lang Châu, Môn Châu, Tô Mậu Châu, and Quảng Lăng, while Đại Việt held control of the Yong, Qin and Lian prefectures.[18] These areas now comprise most of modern Vietnam's Cao Bằng Province and Lạng Sơn Province.[18] In 1082, after a long period of mutual isolation, Emperor Lý Nhân Tông of Đại Việt returned Yong, Qin, and Lian prefectures back to Song authorities, along with their prisoners of war, and in return Song relinquished its control of four prefectures and the county of Đại Việt, including the Nùng clan's home of Quảng Nguyên.[18] Further negotiations took place from July 6 to August 8, 1084 and were held at Song's Yongping garrison in southern Guangnan, where Lý's Director of Military Personnel Lê Van Thình (fl. 1075–1096) convinced Song to fix the two countries' borders between Quảng Nguyên and Guihua prefectures.[19]

Aftermath

An aftermath of the war that still exists today resulted from an agreement that was negotiated by both sides that fixed the two country's borders; the resulting line of demarcation exists largely unmodified to the present day.[20]

In Vietnam

During the Lý defense against the Song counteroffensive in which Song forces nearly breached into the Đại Việt capital of Thăng Long, general Lý Thường Kiệt wrote a famous poem named Nam quốc sơn hà which he then recited in front of his army in order to boost the morale of his men before the battle of Nhu Nguyệt River. The poem, dubbed retroactively as Vietnam's first Declaration of Independence asserted the sovereignty of Đại Việt rulers over its lands. The poem reads:[21][22]

| Original Chinese | Sino-Vietnamese | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| 南國山河南帝居 |

Nam quốc sơn hà nam đế cư Tiệt nhiên định phận tại thiên thư Như hà nghịch lỗ lai xâm phạm Nhữ đẳng hành khan thủ bại hư. |

Over Mountains and Rivers of the South, reigns the Emperor of the South As it stands written forever in the Book of Heaven |

In China

In China, the Siege of Yongzhou during the Lý invasion was depicted in a Lianhuanhua book, which is a type of small palm-sized picture books containing sequential drawings developed in China during the early 20th century. The illustration on page 142, painted by Xiong Kong Cheng (熊孔成), describes the bravery of Su Jian, who, with only three thousand men was able to put up a fierce, forty-two day, resistance against Lý forces before finally succumbing to vastly superior numbers.[14]

References

Citations

- ↑ Anderson 2008, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ 脫脫等《宋史》,卷四百四十六,列傳第二百五,13157頁。

- 1 2 李燾《續資治通鑑長編》卷二百七十四,6700頁。

- ↑ 《越史略》(《欽定四庫全書·史部》第466冊),588頁。

- ↑ 潘輝黎等. 第一章 如月大捷. 《越南民族歷史上的幾次戰略決戰》. 戴可來譯. 北京: 世界知識出版社. 1980年: 26頁.

- 1 2 3 Chapuis 1995, p. 77

- ↑ Xu Zizhi Tongjian Changbian《長編》卷三百上載出師兵員“死者二十萬”,“上曰:「朝廷以交址犯順,故興師討罪,郭逵不能剪滅,垂成而還。今廣源瘴癘之地,我得之未為利,彼失之未為害,一夫不獲,朕尚閔之,况十死五六邪?」又安南之師,死者二十萬,朝廷當任其咎。《續資治通鑑長編·卷三百》”。 《越史略》載廣西被殺者“無慮十萬”。 《玉海》卷一九三上稱“兵夫三十萬人冒暑涉瘴地,死者過半”。

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 191.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 198.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 195–198.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 206-207.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 207–208.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Anderson (2008), 208.

- 1 2 "卡通之窗─血戰邕州" (in Chinese).

- 1 2 Cœdès, George (1966). The Making of South East Asia. University of California Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780520050617.

- ↑ 李燾《續資治通鑑長編》卷二百七十七.熙寧九年八月壬子條,6780頁。

- 1 2 Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 43

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anderson (2008), 209.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 210.

- ↑ Anderson (2008), 191–192.

- ↑ James Anderson The Rebel Den of Nùng Trí Cao: Loyalty and Identity 2007 p. 214 note 88

- ↑ Vuving, Alexander L. (June 2000). "The References of Vietnamese States and the Mechanisms of World Formation" (PDF). Asienkunde.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

Sources

- Anderson, James A. (2008). "'Treacherous Factions': Shifting Frontier Alliances in the Breakdown of Sino-Vietnamese Relations on the Eve of the 1075 Border War", in Battlefronts Real and Imagined: War, Border, and Identity in the Chinese Middle Period, 191–226. Edited by Don J. Wyatt. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6084-9.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995), A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-29622-7

- Trần, Trọng Kim (1971), Việt Nam sử lược (in Vietnamese), Saigon: Center for School Materials