Carquinez Bridge

| Carquinez Bridge | |

|---|---|

The Carquinez Bridge in 2008: (from closest to furthest) a 2003 suspension bridge and the 1958 cantilever bridge | |

| Coordinates | 38°03′39″N 122°13′33″W / 38.0608°N 122.2257°WCoordinates: 38°03′39″N 122°13′33″W / 38.0608°N 122.2257°W |

| Carries |

8 lanes of |

| Crosses | Carquinez Strait |

| Locale | Crockett and Vallejo, California, U.S. |

| Official name | Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge (suspension bridge only) |

| Other name(s) | Zampa Bridge, Vallejo Bridge |

| Owner | State of California |

| Maintained by | California Department of Transportation and the Bay Area Toll Authority |

| ID number | 28+0352 (2003 span), 23+0015L (1927 span), 23+0015R (1958 span) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design |

Cantilever bridge (Eastbound) Suspension bridge (Westbound) |

| Total length | 3,465 feet (1,056 m) or 0.66 miles (1.06 km) (suspension bridge), 3,300 feet (1,000 m) (cantilever bridge) |

| Width | 84 feet (26 m) (suspension deck), 52 feet (16 m) (cantilever deck) |

| Height | 410 feet (120 m) (suspension tower) |

| Longest span | 2,390 feet (730 m) (suspension span) |

| Clearance below | 148 feet (45 m) (suspension bridge), 140 feet (43 m) (cantilever bridge) |

| History | |

| Opened |

May 21, 1927 (original span) November 25, 1958 (eastbound) November 11, 2003 (westbound) |

| Closed | September 4, 2007 (original span) |

| Statistics | |

| Toll |

Cars (eastbound only) $5.00 (cash or FasTrak), $2.50 (carpools during peak hours, FasTrak only) |

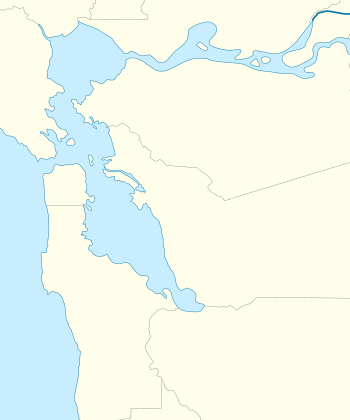

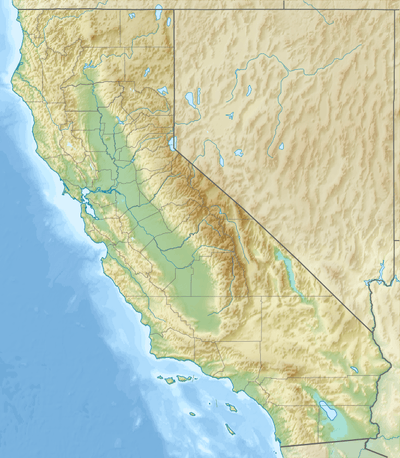

Carquinez Bridge Location in San Francisco Bay Area  Carquinez Bridge Carquinez Bridge (California)  Carquinez Bridge Carquinez Bridge (the US) | |

The Carquinez Bridge, is a pair of parallel bridges spanning the Carquinez Strait, at the northeastern end of San Francisco Bay. They form the part of Interstate 80 between Crockett and Vallejo, California. The name Carquinez Bridge originally referred to a single cantilever bridge built in 1927, which was part of the direct route between San Francisco and Sacramento. A second parallel cantilever bridge was completed in 1958 to deal with the increased traffic. Later, seismic problems made the 1927 span unsafe in case of an earthquake, and led to the construction, and 2003 opening, of a replacement: a suspension bridge officially named the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge, in memory of iron worker Al Zampa, who played an integral role in the construction of numerous San Francisco Bay Area bridges. The Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge carries westbound traffic from Vallejo to Crockett, and the 1958 cantilever span carries eastbound traffic.

History and description

The first regular crossing of the Carquinez Strait began in the mid-1800s as a ferry operated between the cities of Benicia and Martinez, six miles upstream from the bridge site. Auto service started on this route in 1913. A train ferry operated between Benicia and Porta Costa from 1879 until 1930 when a rail bridge opened. Ferry service at the site of the bridge started in 1913 by the Rodeo-Vallejo Ferry Company.[1]

Original span (1927–2007)

The original steel cantilever bridge was designed by Robinson & Steinman and dedicated on May 21, 1927. Prior to this, crossing the Carquinez Strait necessitated the use of ferries. The bridge cost $8 million to build. It was the first major crossing of the San Francisco Bay[2] and a significant technological achievement in its time.

Upon its completion, the span became part of the Lincoln Highway. This historic transcontinental roadway's original alignment, like the Transcontinental Railroad that preceded it nearly sixty years earlier, chose to avoid crossing the Carquinez Strait entirely. The preferred option, given the engineering limitations of the day, was to skirt around the Delta by going south from Sacramento through Stockton, then proceeding west across the San Joaquin River and over the Altamont Pass, and finally reaching Oakland from the south; a route that would later become U.S. Route 50 and ultimately Interstates 5, 205, and 580. This circuitous route, several miles longer, and traversing a rather formidable mountain pass, was preferable to crossing the Carquinez Strait, a deep channel with strong currents and frequent high winds. For decades, building a bridge across the Carquinez Strait was considered prohibitively expensive and technologically risky. Once the bridge was built however, driving from Sacramento to the East Bay became much more direct. The Carquinez Bridge provided a welcome alternative route from the Central Valley to the Bay Area, one that no longer required loading one's vehicle onto and off of a ferry. With the bridge completed, the Lincoln Highway was realigned to cross the Sacramento River, then proceed southwest through Davis and Vallejo, across the Carquinez Bridge, and along the shores of the San Pablo and San Francisco bays to Richmond and Oakland; becoming U.S. Route 40, and ultimately Interstate 80.

After the Loma Prieta earthquake engineers determined that the aging 1927 span was seismicly unstable, and that a retrofit was impossible. The decision was made to replace it with a new suspension bridge. The 1927 span was temporarily used to hold eastbound traffic while the 1958 eastbound span underwent a seismic retrofit, deck and superstructure rehabilitation, and painting to extend its serviceable life.[3] The old 1923 cantelever bridge was dismantled three years after the opening of its replacement; with completion on September 4, 2007. A 3,000-pound bronze bell atop one of the bridge piers was removed and placed into storage. The bell will eventually be displayed in a new museum to be built at the Oakland end of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

Parallel span (1958)

In 1958, at a cost of $38 million[4] a second bridge was built alongside and to the east of the bridge. This new span, nearly identical to the first, was needed to accommodate the ever-increasing levels of traffic. The three-lane 1927 span, originally two-way, now served only westbound drivers while the 1958 span handled eastbound traffic.

Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge (2003 replacement span)

At a cost of $240 million a new suspension bridge was built, to the west of the two earlier bridges, by the Joint Venture consisting of Flatiron Structures of Longmont, Co., FCI Constructors of Benicia, Ca., and the Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company of Darlington, England.[4]

This new bridge was named the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge, after an ironworker who worked on a number of the San Francisco Bay Area bridges, including the Golden Gate Bridge, and the original 1927 Carquinez span. The bridge was dedicated on November 8, 2003 and opened for traffic on November 11, 2003. Originally, the plan was to dedicate the bridge on November 15, but complications involving then just-recalled Governor Gray Davis and the transfer power to Arnold Schwarzenegger resulted in the date being moved. The coins minted to commemorate the event have the original date on them.[5]

The new suspension bridge, consists of the south anchorage, a transition pier, the South and North towers, and the north anchorage. It has spans of 147 m, 728 m, and 181 m. for a total span of 0.66 miles (1,060 m). It features a pedestrian and bicycle path, part of a bike trail which it is hoped will eventually circle the entire Bay Area. The towers are each founded on two footings, which are each supported by six vertical, 3-metre-diameter (9.8 ft) steel shells infilled with reinforced concrete, followed by 2.7-metre-diameter (8.9 ft) drilled shafts in rock, i.e., cast-in-drilled hole, or CIDH, piles. The total length of the CIDH pile at the South Tower is approximately 89 m, with about 43 m of drilled shaft in rock. The total length of the CIDH pile at the North Tower ranges from 49 to 64 m, with about 16 to 26 m of drilled shaft in rock. The design parameters used for the South Tower piles were later confirmed by a pile load test. Additional field investigations during construction revealed significant variations in rock conditions at the North Tower, resulting in the redesign of the length of the piles. Major construction challenges encountered during construction of the South Tower piles, and the revised construction procedure, i.e., under-reaming, used by the constructor to mitigate caving.

Materials for the New Bridge came from all over the world:

- Steel Caissons for CIDH: XKT Engineering – Vallejo, California

- Orthotropic Deck Sections: IHI – Japan

- Tower and Splay Saddles:

- Castings: Sheffield Steel – England

- Finishing and Machining: Kvaerner – England

- Main Cable Wire: Bridon – England

- Wire for Cable Wrapping: Canada

- Cable Bands: France

- Suspenders (Hardware, Casting, Fabrication): WRCA – St. Joseph, Missouri

- (3) Maintenance Travelers Under Deck Sections: Jesse Engineering – Tacoma, Washington

Tolls

Tolls are collected only from automotive traffic headed eastbound, towards Vallejo at the toll plaza on the north side of the bridge. Although the 2003 Al Zampa Memorial Bridge is newer than the other span, no toll is charged in that direction, continuing the practice of when the now-demolished 1927 span was still in operation. Since July 2010, the toll rate for passenger cars is $5. During peak traffic hours, carpool vehicles carrying two or more people or motorcycles pay a discounted toll of $2.50.[6][7] For vehicles with more than two axles, the toll rate is $5 per axle.[8] Drivers may either pay by cash or use the FasTrak electronic toll collection device.

Historical toll rates

Crossing the original 1926 bridge required a toll, but tolls were removed soon after the state bought the bridge in 1940. Tolls in 1926 were originally set at $0.60 per car plus $0.10 per passenger. This was reduced in 1938 to $0.45 per car plus $0.05 per passenger. After the state took ownership, tolls were immediately reduced to $0.30 per car. In 1942, tolls were further reduced to $0.25 before being removed in 1945. Tolls were reinstated in 1958 with the completion of the parallel span, set again at $0.25. It was increased to $0.35 in 1970, and then $0.40 in 1978.[9]

The basic toll (for automobiles) on the seven state-owned bridges, including the Carquinez Bridge, was raised to $1 by Regional Measure 1, approved by Bay Area voters in 1988.[10] A $1 seismic retrofit surcharge was added in 1998 by the state legislature, originally for eight years, but since then extended to December 2037 (AB1171, October 2001).[11] On March 2, 2004, voters approved Regional Measure 2, raising the toll by another dollar to a total of $3. An additional dollar was added to the toll starting January 1, 2007, to cover cost overruns concerning the replacement of the eastern span.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, a regional transportation agency, in its capacity as the Bay Area Toll Authority, administers RM1 and RM2 funds, a significant portion of which are allocated to public transit capital improvements and operating subsidies in the transportation corridors served by the bridges. Caltrans administers the "second dollar" seismic surcharge, and receives some of the MTC-administered funds to perform other maintenance work on the bridges. The Bay Area Toll Authority is made up of appointed officials put in place by various city and county governments, and is not subject to direct voter oversight.[12]

Due to further funding shortages for seismic retrofit projects, the Bay Area Toll Authority again raised tolls on all seven of the state-owned bridges in July 2010. The toll rate for autos on the Carquinez Bridge was thus increased to $5.[13]

Structural Health Monitoring on the westbound span

A long-term wireless structural monitoring system was installed starting in the summer of 2010 with the system in continuous operation since. The wireless monitoring system installed is based on the use of a wireless sensor node developed at the University of Michigan termed Narada. Narada is a wireless data acquisition system specially designed for monitoring civil infrastructure systems where low power consumption (i.e., rechargeable battery operated), high data resolution (i.e., 16-bits or higher), and long communication ranges (i.e., 500 m or longer) are all required system capabilities. On the New Carquinez Suspension Bridge, a total of 33 Narada nodes each capable of collecting up to 4 independent channels of data were installed over a 2-year period with various sensing transducers interfaced: 23 tri-axial accelerometers (to measure deck and tower accelerations), 3 strain potentiometers (to measure longitudinal movement between the deck and the towers), 33 battery voltage detectors (to monitor the battery level on each Narada), 9 thermistors (to measure the ambient and girder temperatures), 2 wind vanes, 2 anemometers and 6 strain gages(to measure deck bending strains). A total of 124 sensing channels have been deployed on the bridge. The Narada nodes are all powered by rechargeable batteries that are continuously charged by solar panels installed on the top deck of the bridge.[14]

Carquinez Bridge in the media

- The 1927 span of the Carquinez Bridge is featured on a Season 4 episode of MythBusters in the Miniature Earthquake Machine segment. This experiment, based upon a claim by inventor Nikola Tesla that his mechanical oscillator produced an earthquake in 1898, employed a small tunable reciprocating mass driver to shake the bridge at its resonance frequency. While not structurally significant, the shaking was felt some distance from the driver.

- An hour-length program, titled Break It Down: "Bridge", documenting the demolition of the 1927 bridge aired on National Geographic Channel, on November 1, 2007

- On October 5, 2007, a man jumped off the new 156-foot-high (48 m) bridge. The Coast Guard, Vallejo Police, and Fire responded to find him on the breakwater. He survived the fall.

- Four books have been published about, or featuring, the Carquinez Bridges:Spanning the Carquinez Strait: The Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge (2003) Cal-Trans, Spanning the Strait: Building the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge (2004) by John V. Robinson, and Al Zampa and the Bay Area Bridges (2005) by John V. Robinson and, most recently, Carquinez Bridge: 1927-2007 (2017) by John V. Robinson

- The bridge was featured in the 2017 Netflix TV series 13 Reasons Why.

See also

References

- ↑ Hope, Andrew (2000). Carquinez Bridge, Spanning Carquinez Strait at Interstate 80, Vallejo, Solano County, CA, Historic American Engineering Record. p. 11.

- ↑ The Barrier Broken – Vallejo Evening Chronicle, May 21, 1927

- ↑ "Old Carquinez Bridge is disappearing" – San Francisco Chronicle, April 25, 2006.

- 1 2 "Bay Area Toll Authority – Bridge Facts – Carquinez Bridge". Bata.mtc.ca.gov. 2011-01-27. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ↑ "Alfred Zampa memorial coins" Archived October 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. – Official Web Site

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Toll Questions". Bay Area Toll Authority. 2010-06-01. Archived from the original on 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ↑ "Toll Increase Information". Bay Area Toll Authority. 2010-06-01. Archived from the original on 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ↑ "Toll Increase Information: Multi-Axle Vehicles". Bay Area Toll Authority. 2012-07-01. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ "History of California's Bridge Tolls" (PDF). Caltrans. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ↑ Regional Measure 1 Toll Bridge Program. bata.mtc.ca.gov; Bay Area Toll Authority. Archived November 1, 2010, at WebCite

- ↑ Dutra, John (October 14, 2001). "AB 1171 Assembly Bill – Chaptered". California State Assembly. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ↑ "About MTC". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. October 15, 2009. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Toll Questions". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ↑ "New Carquinez Bridge – LIST Wiki". Smartstructure.engin.umich.edu. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carquinez Bridge. |

- Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge Foundation

- Bridging the Bay History of the Carquinez Bridge, as well as other bridges.

- Caltrans New Carquinez Bridge page

- Building the Al Zampa Bridge – Site written by Dick McCabe Jr, a union ironworker who worked on the bridge with pictures of the construction and a journal of the construction progress.

- Live Toll Prices for Carquinez Bridge

- Carquinez Strait Bridge (1927) at Structurae

- Carquinez Strait Bridge (1958) at Structurae

- Alfred Zampa Memorial (New Carquinez) Bridge (2003) at Structurae

- Break it Down: "Bridge" on National Geographic Channel.

- Bay Area Toll Authority Bridge Facts on Carquinez Bridge.

- Publisher's Web site for Spanning the Strait: Building the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge, John V. Robinson's book about the new bridge.

- Third Carquinez Strait Bridge OAPC Consulting Engineers alternatives and selection report

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-297, "Carquinez Bridge, Spanning Carquinez Strait at Interstate 80, Vallejo, Solano County, CA", 126 photos, 59 data pages, 8 photo caption pages