Black Hole of Calcutta

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a small prison or dungeon in Fort William where troops of Siraj ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, held British prisoners of war for three days on 20 June 1756.

John Zephaniah Holwell, one of the British prisoners and an employee of the East India Company, said that, after the fall of Fort William, the surviving British soldiers, Anglo-Indian soldiers, and Indian civilians were imprisoned overnight in conditions so cramped that many people died from suffocation and heat exhaustion, and that 143 of 164 prisoners of war imprisoned there died.[1]

Background

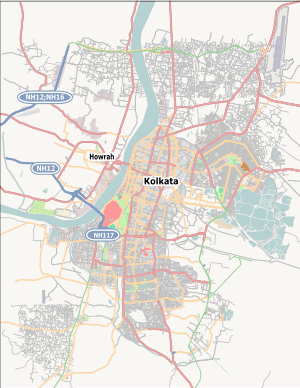

Coordinates: 22°34′24″N 88°20′53″E / 22.573357°N 88.347979°E

Fort William was established to protect the East India Company's trade in the city of Calcutta, the principal city of the Bengal Presidency. In 1756 India, there existed the possibility of imperial confrontation with military forces of the Kingdom of France, so the British reinforced the fort.

Meanwhile, Siraj ud-Daulah, the local ruler was unhappy with the Company's political interference in the internal affairs of his province; the British merchants were undermining his political power. As the Nawab, Siraj perceived a threat to Bengali independence and himself. He ordered the immediate cessation of the reinforcement of Fort William, but the Company paid no heed to the native ruler.

In consequence to that British indifference to local Bengali authority, Siraj ud-Daulah organised his army and laid siege to Fort William. In an effort to survive the losing battle, the British commander ordered the surviving soldiers of the garrison to escape, yet left behind 146 soldiers under the civilian command of John Zephaniah Holwell, a senior bureaucrat of the East India Company, who had been a military surgeon in earlier life.[2]

Moreover, the desertions of allied Indian troops made ineffective the British defence of Fort William, which fell to the siege of Bengali forces on 20 June 1756. The surviving defenders who were captured and made prisoners-of-war numbered between 64 and 69, along with an unknown number of Anglo-Indian soldiers and civilians who earlier had been sheltered in Fort William.

The Holwell account

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: “On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us”.[3] After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at 8.00 p.m., the jailers locked the prisoners in the fort’s prison — “the black hole” in soldiers' slang — a small room that measured 4.30m. × 5.50 m (14 feet × 18 feet).[4] The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at 6.00 a.m., only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.[2]

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived.[2] D.L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and shock.[5] Busteed reports that the many non-combatants present in the fort when it was captured makes infeasible a precise number of people killed.[6] Regarding responsibility for the maltreatment and the deaths in the Black Hole of Calcutta, Holwell said, “it was the result of revenge and resentment, in the breasts of the lower Jemmaatdaars [sergeants], to whose custody we were delivered, for the number of their order killed during the siege.”[3]

Concurring with Holwell, Wolpert said that Siraj-ud-Daulah did not order the imprisonment and was not informed of it.[2] The physical description of the Black Hole of Calcutta corresponds with Holwell’s point of view:

The dungeon was a strongly barred room, and was not intended for the confinement of more than two or three men at a time. There were only two windows, and a projecting veranda outside, and thick iron bars within impeded the ventilation, while fires, raging in different parts of the fort, suggested an atmosphere of further oppressiveness. The prisoners were packed so tightly that the door was difficult to close.

One of the soldiers stationed in the veranda was offered 1,000 rupees to have them removed to a larger room. He went away, but returned saying it was impossible. The bribe was then doubled, and he made a second attempt with a like result; the nawab was asleep, and no one dared wake him.

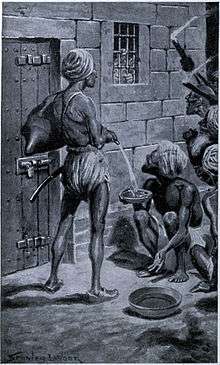

By nine o'clock several had died, and many more were delirious. A frantic cry for water now became general, and one of the guards, more compassionate than his fellows, caused some [water] to be brought to the bars, where Mr. Holwell and two or three others received it in their hats, and passed it on to the men behind. In their impatience to secure it nearly all was spilt, and the little they drank seemed only to increase their thirst. Self-control was soon lost; those in remote parts of the room struggled to reach the window, and a fearful tumult ensued, in which the weakest were trampled or pressed to death. They raved, fought, prayed, blasphemed, and many then fell exhausted on the floor, where suffocation put an end to their torments.

About 11 o'clock the prisoners began to drop off, fast. At length, at six in the morning, Siraj-ud-Daulah awoke, and ordered the door to be opened. Of the 146 only 23, including Mr. Holwell [from whose narrative, published in the Annual Register & The Gentleman's Magazine for 1758, this account is partly derived], remained alive, and they were either stupefied or raving. Fresh air soon revived them, and the commander was then taken before the nawab, who expressed no regret for what had occurred, and gave no other sign of sympathy than ordering the Englishman a chair and a glass of water. Notwithstanding this indifference, Mr. Holwell and some others acquit him of any intention of causing the catastrophe, and ascribe it to the malice of certain inferior officers, but many think this opinion unfounded.

Afterwards, when the prison of Fort William was opened, the corpses of the dead men were thrown into a ditch. Moreover, as prisoners, Holwell and three other men were transferred to Murshidabad.

Imperial aftermath

The remaining survivors of the Black Hole of Calcutta were freed after the victory of a relief expedition commanded by Sir Robert Clive. After news of Calcutta's capture was received by the British in Madras (now Chennai) in August 1756, Lieut. Col. Robert Clive was sent to retaliate against the Indians. With his troops and local Indian allies, Clive recaptured Calcutta in January 1757, and went on to defeat Siraj ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey, which resulted in Siraj being overthrown as Nawab of Bengal, and killed.[2]

The Black Hole of Calcutta was later used as a warehouse.

Monument to the victims

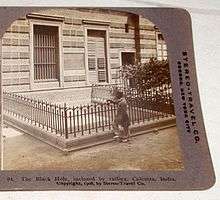

In memoriam of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre-high obelisk; it now is in the graveyard of (Anglican) St. John's Church, Kolkata. Holwell had erected a tablet on the site of the 'Black Hole' to commemorate the victims but, at some point before 1822 (the precise date is uncertain), it disappeared. Lord Curzon, on becoming Viceroy in 1899, noticed that there was nothing to mark the spot and commissioned a new monument, mentioning the prior existence of Holwell's; it was erected in 1901 at the corner of Dalhousie Square (now B. B. D. Bagh), which is said to be the site of the 'Black Hole'.[7] At the apex of the Indian independence movement, the presence of this monument in Calcutta was turned into a nationalist cause célèbre. Nationalist leaders, including Subhas Chandra Bose, lobbied energetically for its removal. The Congress and the Muslim League joined forces in the anti-monument movement. As a result, Abdul Wasek Mia of Nawabganj thana, a student leader of that time, led the removal of the monument from Dalhousie Square in July 1940. The monument was re-erected in the graveyard of St John's Church, where it remains.

The 'Black Hole' itself, being merely the guardroom in the old Fort William, disappeared shortly after the incident when the fort itself was taken down to be replaced by the new Fort William which still stands today in the Maidan to the south of B. B. D. Bagh. The precise location of that guardroom is in an alleyway between the General Post Office and the adjacent building to the north, in the north west corner of B.B.D. Bagh. The memorial tablet which was once on the wall of that building beside the GPO can now be found in the nearby postal museum.

"List of the smothered in the Black Hole prison exclusive of sixty-nine, consisting of Dutch and British sergeants, corporals, soldiers, topazes, militia, whites, and Portuguese, (whose names I am unacquainted with), making on the whole one hundred and twenty-three persons."

Holwell's list of the victims of the Black Hole of Calcutta:

Of Counsel — E. Eyre, Esqr., Wm. Baillie, Esqr., the Rev. Jervas Bellamy.

Gentlemen in the Service — Messrs. Jenks, Revely, Law, Coales, Valicourt, Jeb, Torriano, E. Page, S. Page, Grub, Street, Harod, P. Johnstone, Ballard, N. Drake, Carse, Knapton, Gosling, Bing, Dod, Dalrymple, V. Ament Theme.

Military Captains — Clayton, Buchanan, Witherington.

Lieutenants — Bishop, Ifays, Blagg, Simson, Bellamy.

Ensigns – Paccard, Scot, Hastings, C. Wedderburn, Dumbleton.

Sergeants, &c. — Sergeant-Major Abraham, Quartermaster Cartwright, Sergeant Bleau (these were sergeants of militia).

Sea Captains — Hunt, Osburne, Purnell (survived the night; died on the morn), Messrs. Carey, Stephenson, Guy, Porter, W. Parker, Caulker, Bendall, Atkinson, Leech, &c., &c.

The list of the men and women who survived their imprisonment in the Black Hole of Calcutta:

Messrs. Holwell, John Zephediah, Court, Secretary Cooke, Lushington, Burdett, Ensign Walcott, Mrs. Carey, Captain Mills, Captain Dickson, Mr. Moran, John Meadows, and twelve military and militia (blacks & whites).[8]

The Black Hole of Calcutta in popular culture

Literature

Thomas Pynchon refers to the Black Hole of Calcutta in the historical novel Mason & Dixon (1997). The character Charles Mason spends much time on Saint Helena with the astronomer Nevil Maskelyne, the brother-in-law of Lord Robert Clive of India; themes of colonialism and racism are discussed in relation to the event. Later in the story, Jeremiah Dixon visits New York City, and attends a secret "Broad-Way" production of the "musical drama", The Black Hole of Calcutta, or, the Peevish Wazir, "executed with such a fine respect for detail. . . ."[9] Pynchon satirically refers to it in the long-running musical revue Oh! Calcutta!, which was played on Broadway for more than 7,000 performances.

Edgar Allan Poe makes reference to the "stifling" of the prisoners in the introduction to "The Premature Burial" (1844).[10] The Black Hole is mentioned in Looking Backward (1888) by Edward Bellamy as an example of the depravity of the past. In the science-fiction novel Omega: The Last Days of the World (1894), by Camille Flammarion, The Black Hole of Calcutta is mentioned for the suffocating properties of Carbonic-Oxide (Carbon Monoxide) upon the British soldiers imprisoned in that dungeon. Eugene O'Neill, in Long Day's Journey into Night, Act 4, Jamie says, "Can't expect us to live in the Black Hole of Calcutta." Patrick O'Brian compared Jack Aubrey's house to the black hole of Calcutta "except that whereas the Hole was hot, dry, and airless", Aubrey's cottage "let in draughts from all sides." The Mauritius Command at 15. Diana Gabaldon mentions briefly the incident in her novel Lord John and the Private Matter (2003). It is also compared with the evil miasma of Calcutta as a whole in Dan Simmons's novel The Song of Kali. Stephen King makes a reference to the Black Hole of Calcutta in his 2004 novel Song of Susannah. In Chapter V of "King Solomon´s Mines" (H.R. Haggard. 1885) the Black Hole of Calcutta is mentioned: "This gave us some slight shelter from the burning rays of the sun, but the atmosphere in that amateur grave can be better imagined than described. The Black Hole of Calcutta must have been a fool to it..." In John Fante's novel "The Road to Los Angeles" (1985), the main character Arturo Bandini recalls when seeing his place of work: "I thought about the Black Hole of Calcutta."

Television

In the period drama Turn: Washington's Spies, the character of John Graves Simcoe claims in Season 4 that he was born in India and that his father died in the Black Hole of Calcutta after being tortured. (In historical reality, Simcoe was born in England and his father died of pneumonia).

In an episode of the Britcom Open All Hours Mr.Arkwright orders his assistant Granville to clean the outside window ledge. He said "There's enough dirt there to fill the Black Hole of Calcutta".

Astronomy

According to Hong-Yee Chiu, a long-time astrophysicist at NASA, the Black Hole of Calcutta was the inspiration for the term black hole referring to regions of space-time resulting from the gravitational collapse of very heavy stars. He recalled hearing physicist Robert Dicke in the early 1960s compare such gravitationally collapsed objects to the infamous prison.[11]

Gallery

Text on the Memorial in St John's Churchyard

Text on the Memorial in St John's Churchyard Black Hole Monument

Black Hole Monument Holwell Monument, c. 1905

Holwell Monument, c. 1905 Inscription dating relocation

Inscription dating relocation Scene of the Black Hole, c. 1905

Scene of the Black Hole, c. 1905

Notes

- ↑ Little, J. H. (1916) ‘The Black Hole — The Question of Holwell's Veracity’ (1916) Bengal: Past and Present, vol. 12. pp. 136–171.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wolpert, Stanley (2009). A New History of India (8th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford UP. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3.

- 1 2 Holwell, John Zephaniah; Friends (1764). "A Genuine Narrative of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen, and Others, who were suffocated in the Black-Hole in Fort-William, at Calcutta, in the Kingdom of Bengal; in the Night succeeding the 20th Day of June, 1756". India Tracts (2nd ed.). London, Great Britain: Becket & de Hondt. pp. 251–76. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English

- ↑ D. L. Prior, Holwell's biographer in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, reports figures of 64 prisoners and 21 survivors.

- ↑ H.E. Busteed Echoes from Old Calcutta (Calcutta) 1908 pp. 30–56

- ↑ Busteed Old Calcutta pp52-6

- ↑ Busteed, 1888 appendix section of Echoes of Old Calcutta

- ↑ Pychon, Thomas, Mason & Dixon, pp. 562–564.

- ↑ "The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 2". Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ↑ Siegfried, Tom, "50 years later, it’s hard to say who named black holes", Science News, retrieved 2 January 2014

References

- Partha Chatterjee. The Black Hole of Empire: History of a Global Practice of Power. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012. 425p. ISBN 9780691152004. Explores the incident itself and the history of using it to expand or critique British rule in India.

- Urs App (2010). The Birth of Orientalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press ( ISBN 978-0-8122-4261-4); contains a 66-page chapter (pp. 297–362) on Holwell.

- Dalley, Jan (2006). The Black Hole: Money, Myth and Empire. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-91447-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black Hole of Calcutta. |

- The Black Hole of Calcutta & The End of Islamic Power in India (1756—1757)

- The Black Hole of Empire – Stanford Presidential Lecture by Partha Chatterjee

- Photo of Calcutta Black Hole Memorial at St. John's Church Complex, Calcutta (Kolkata)

- Partha Chatterjee and Ayça Çubukçu, "Empire as a Practice of Power: Introduction," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 41, No. 1, 9 October 2012. Interview with Chatterjee.