Anti-Qing sentiment

Anti-Qing sentiment (Chinese: 反淸; pinyin: fǎn Qing) refers to a sentiment principally held in China against the Manchu ruling during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), which was accused by a number of opponents of being barbarian. The Qing was accused of destroying traditional Han culture by forcing Han to wear their hair in a queue in the Manchu style. It was blamed for suppressing Chinese science, causing China to be transformed from the world's premiere power to a poor, backwards nation. The people of the Eight Banners lived off government pensions unlike the general Han civilian population.

The rallying slogan of anti-Qing activists was "Fǎn Qīng fù Míng" (simplified Chinese: 反淸复明; traditional Chinese: 反淸復明; literally: "Oppose Qing and restore Ming").

In the broadest sense, an anti-Qing activist was anyone who engaged in anti-Manchu direct action. This included people from many mainstream political movements and uprisings, such as Taiping Rebellion, the Xinhai Revolution, the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, the Revive China Society, the Tongmenghui, the Panthay Rebellion, White Lotus Rebellion, and others.

Ming loyalism in the early Qing

Muslim Ming loyalists

Hui Muslim Ming loyalists under Mi Layin and Ding Guodong fought against the Qing to restore a Ming prince to the throne from 1646-1650. When the Qing dynasty invaded the Ming dynasty in 1644, Muslim Ming loyalists in Gansu led by Muslim leaders Milayin[1] and Ding Guodong led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore the Ming Prince of Yanchang Zhu Shichuan to the throne as the emperor.[2] The Muslim Ming loyalists were supported by Hami's Sultan Sa'id Baba and his son Prince Turumtay.[3][4][5] The Muslim Ming loyalists were joined by Tibetans and Han Chinese in the revolt.[6] After fierce fighting, and negotiations, a peace agreement was agreed on in 1649, and Milayan and Ding nominally pledged allegiance to the Qing and were given ranks as members of the Qing military.[7] When other Ming loyalists in southern China made a resurgence and the Qing were forced to withdraw their forces from Gansu to fight them, Milayan and Ding once again took up arms and rebelled against the Qing.[8] The Muslim Ming loyalists were then crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin, Ding Guodong, and Turumtay killed in battle.

The Confucian Hui Muslim scholar Ma Zhu (1640–1710) served with the southern Ming loyalists against the Qing.[9]

Koxinga

The Ming loyalist general Zheng Chenggong, better known by his title Koxinga, led a military movement to oppose the Qing dynasty from 1646 to 1662. He established the Kingdom of Tungning on the island of Taiwan.

Joseon

Joseon Korea operated within the Ming tributary system and had a strong alliance with the Ming during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98). This put Joseon in a dilemma when both Nurhaci and the Ming requested support. King Gwanghaegun tried to maintain neutrality, but most of his officials opposed him for not supporting the Ming, a longstanding ally.

In 1623 King Gwanghaegun was deposed and replaced by King Injo (r. 1623–1649), who banished Gwanghaejun's supporters. Reverting his predecessor's foreign policy, the new king decided to support the Ming openly, but a rebellion led by military commander Yi Gwal erupted in 1624 and wrecked Joseon's military defenses in the north. Even after the rebellion had been suppressed, King Injo had to devote military forces to ensure the stability of the capital, leaving fewer soldiers to defend the northern borders.[10]

The Manchus invaded Korea twice, in 1627 and 1636, eventually forcing Joseon to sever its ties with the Ming and instead to become a tributary of the Manchus. However, there remained popular opposition to the Manchus in Korea. Joseon continued to use the Ming calendar rather than the Qing calendar, and Koreans continued to wear Ming-style clothing and hairstyles, rather than the Manchu queue. After the fall of the Ming dynasty, Joseon Koreans saw themselves as continuing the traditions of Neo-Confucianism.[11]

Anti-Qing rebellions

Mongol Rebellions

The Mongols under Qing rule were divided into three primary groups- the Inner Mongols, the Outer Khalkha Mongols, and the Eastern Oirat Mongols.

The Inner Mongolian Chahar Khan Ligdan Khan, a descendant of Genghis Khan, opposed and fought against the Qing until he died of smallpox in 1634. Thereafter, the Inner Mongols under his son Ejei Khan surrendered to the Qing in 1636 and was given the title of Prince (Qin Wang, 親王), and Inner Mongolian nobility became closely tied to the Qing royal family and intermarried with them extensively. Ejei Khan died in 1661 and was succeeded by his brother Abunai. After Abunai showed disaffection with Manchu Qing rule, he was placed under house arrested in 1669 in Shenyang and the Kangxi Emperor gave his title to his son Borni. Abunai then bid his time and then he and his brother Lubuzung revolted against the Qing in 1675 during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, with 3,000 Chahar Mongol followers joining in on the revolt. The Qing then crushed the rebels in a battle on April 20, 1675, killing Abunai and all his followers. Their title was abolished, all Chahar Mongol royal males were executed even if they were born to Manchu Qing princesses, and all Chahar Mongol royal females were sold into slavery except the Manchu Qing princesses. The Chahar Mongols were then put under the direct control of the Qing Emperor unlike the other Inner Mongol leagues which maintained their autonomy.

The Khalkha Mongols were more reluctant to come under Qing rule, only submitting to the Kangxi Emperor after they came under an invasion from the Oirat Mongol Dzungar Khanate under its leader Galdan.

The Oirat Khoshut Upper Mongols in Qinghai rebelled against the Qing during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor but were crushed and defeated.

The Oirat Mongol Dzungars in the Dzungar Khanate offered outright resistance and war against the Qing for decades until they Qing annihilated the Dzungars in the Dzungar genocide. Khalkha Mongol rebels under Prince Chingünjav had plotted with the Dzungar leader Amursana and led a rebellion against the Qing at the same time as the Dzungars. The Qing crushed the rebellion and executed Chingünjav and his entire family.

During the Xinhai Revolution, the Outer Khalkha Mongols staged an uprising against the Qing and expelled the Manchu Ambans.

Taiping Rebellion

Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全, Hóng Xiùquán) was a Hakka Chinese who was the leader of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) against the Qing dynasty. He proclaimed himself to be the Heavenly King, established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and called Jesus Christ his brother.

Genocide and extermination of Manchus

Driven by their fierce hatred of Manchus, the Taiping launched a massive genocide against the Manchus to exterminate their entire race.

The genocide of Manchus was incredible, in every city they captured, the Taiping immediately rushed into the Manchu quarter of the city and killed all the Manchus. One Qing loyalist observed in the province of Hunan of the genocidal atrocities committed by the Taiping against the Manchus and wrote of the "pitiful Manchus", Manchu men, women and children who were exterminated by the Taiping with their swords. Once Hefei capitulated, the Taiping rushed into the Manchu quarter shouting "Kill the demons (Manchus)!" while engaging in their genocidal massacre of all the Manchus living there. Ningbo's entire Manchu population was also annihilated by them.[12] The Taiping exterminated 40,000 Manchus in Nanjing.[13] On 27 October 1853 they crossed the Yellow River in T'sang-chou and butchered 10,000 Manchus.[14]

Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856)

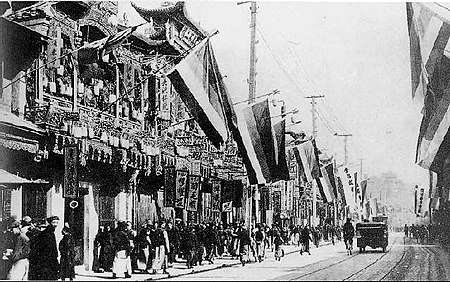

When news reached their ears that the Taipings succeeded in conquered Nanjing, the anti-Manchu Cantonese in the Pearl River Delta saw this as an opportunity and possibility of overthrowing the Manchus to restore Han rule over China, and began the Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856). These rebels were called 'Red Turbans' because of the red headscarves they wore.[15]

The Red Turban Rebellion was initially quite successful as the rebels gained control of a considerable amount of territory. On July 1854, Foshan was occupied by the rebel.[16] In a desperate attempt to the eradicate any facilities which may support the Red Turbans, the Qing forces burnt the northern suburbs in Guangzhou to prevent it from sheltering the rebels.

The rebellion was ultimately defeated in 1856, which was followed by the mass execution of suspected sympathisers and participants of the rebellion.

Panthay Rebellion

The Panthay Rebellion leader Du Wenxiu declared his intention of overthrowing the Qing and driving the Manchus out of China. The rebellion started after massacres of Hui perpetrated by the Manchu authorities.[17] Du used anti-Manchu rhetoric in his rebellion against the Qing, calling for Han to join the Hui to overthrow the Manchu Qing after 200 years of their rule.[18][19] Du invited the fellow Hui Muslim leader Ma Rulong to join him in driving the Manchu Qing out and "recover China".[20] For his war against Manchu "oppression", Du "became a Muslim hero", while Ma Rulong defected to the Qing.[21] On multiple occasions Kunming was attacked and sacked by Du Wenxiu's forces.[22][23] His capital was Dali.[24] The revolt ended in 1873.[25] Du Wenxiu is regarded as a hero by the present day government of China.[26]

Tibetan rebellions

Tibetan Buddhist Lamas rebelled against the Qing at Batang during the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion, assassinating the Manchu leader Fengquan, and also killing French Catholic missionaries and Tibetan converts to Catholicism.

Late-Qing revolutionaries

Sun Yat-sen

| “ | To restore our national independence, we must first restore the Chinese nation. To restore the Chinese nation, we must drive the barbarian Manchus back to the Changbai Mountains. To get rid of the barbarians, we must first overthrow the present tyrannical, dictatorial, ugly, and corrupt Qing government. Fellow countrymen, a revolution is the only means to overthrow the Qing government! | ” |

Zou Rong

Born in Sichuan province in West China in 1885 to a merchant family, Zou (1885–1905) received a classical education but refused to sit for the civil service exams. He worked as a seal carver while pursuing classical studies. He gradually became interested in Western ideas and went to Japan to study in 1901, where he was exposed to radical revolutionary and anti-Manchu ideas.

Here are some quotations of Zou Rong:

"Sweep away millennia of despotism in all its forms, throw off millennia of slavishness, annihilate the five million and more of the furry and horned Manchu race, cleanse ourselves of 260 years of harsh and unremitting pain"

"I do not begrudge repeating over and over again that internally we are slaves of the Manchus and suffering from their tyranny, externally we are being harassed by the Powers, and we are doubly enslaved."

"Kill the emperor set up by the Manchus as a warning to the myriad generations that despotic government is not to be revived."

"Settle the name of the country as the Republic of China."[27]

Overthrow of the Qing

The Xinhai Revolution (Chinese: 辛亥革命; pinyin: Xīnhài gémìng) of 1911 was catalysed by the triumph of the Wuchang Uprising, when the victorious Wuchang revolutionaries telegraphed the other provinces asking them to declare their independence, and 15 provinces in Southern China and Central China did so.[28]

The revolution also saw widespread violence and massacres targeted against Manchu Banner garrisons in cities throughout China.[29] These notorious massacres of Manchus include the mass-slaughter which happened in Wuhan where 10,000 Manchus were butchered and in Xi'an where another 20,000 Manchus were obliterated.[30]

Finally after more than two centuries, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown and China was established into a new republic.

Texts which contained anti-Manchu content were banned by President Yuan Shikai during the Republic of China (1912–49).[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 298. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 53. ISBN 0295800550. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 54. ISBN 0295800550. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 3447040912. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 55. ISBN 0295800550. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ WAKEMAN JR., FREDERIC (1986). GREAT ENTERPRISE. University of California Press. p. 802. ISBN 0520048040. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ WAKEMAN JR., FREDERIC (1986). GREAT ENTERPRISE. University of California Press. p. 803. ISBN 0520048040. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Rajeswary Ampalavanar; Pierce, Justin, eds. (2013). Charities in the Non-Western World: The Development and Regulation of Indigenous and Islamic Charities. Routledge. ISBN 1317938526. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais 2006, p. 349

- ↑ Holcombe 2011, p. 176

- ↑ Thomas H. Reilly (2011). The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire. University of Washington Press. Copyright. p. 139. ISBN 9780295801926.

- ↑ Matthew White (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W. W. Norton. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- ↑ Micheal Clodfelter. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures. Mcfarland. p. 256.

- ↑ Kingsley Bolton and Christopher Hutton (2010). Triad Societies: Western Accounts of the History, Sociology and Linguistics of Chinese Secret Societies, Volume 5. p. 59.

- ↑ Samuel Wells Williams. The Middle Kingdom, Volume II, Part 2. p. 630.

- ↑ Schoppa, R. Keith (2008). East Asia: identities and change in the modern world, 1700-present (illustrated ed.). Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 58. ISBN 0132431467. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Dillon, Michael (1999). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Curzon Press. p. 59. ISBN 0700710264. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Dillon, Michael (2012). China: A Modern History (reprint ed.). I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 1780763816. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Atwill, David G. (2005). The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856-1873 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0804751595. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Asian Research Trends, Volumes 3-4. Contributor Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan). Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. 1993. p. 137. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Mansfield, Stephen (2007). China, Yunnan Province. Compiled by Martin Walters (illustrated ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 69. ISBN 1841621692. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ China's Southwest. Regional Guide Series. Contributor Damian Harper (illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. 2007. p. 223. ISBN 1741041856. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Giersch, Charles Patterson (2006). Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China's Yunnan Frontier (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0674021711. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Mosk, Carl (2011). Traps Embraced Or Escaped: Elites in the Economic Development of Modern Japan and China. World Scientific. p. 62. ISBN 9814287520. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Comparative Civilizations Review, Issues 32-34. 1995. p. 36. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Zou Rong The Revolutionary Army". Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ↑ Liu, Haiming. [2005] (2005). The Transnational History of a Chinese Family: Immigrant Letters, Family Business and Reverse Migration. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3597-2, ISBN 978-0-8135-3597-5.

- ↑ Rhoads 2011, pp. 188-204.]

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington. p. 190.

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.