Anglo-Saxon Christianity

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon Society and Culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

| Power and organization |

| Religion |

| General |

|---|

| Early |

| Medieval |

| Early Modern |

| Eighteenth century to present |

The history of Christianity in England from the Roman departure to the Norman Conquest is often told as one of conflict between the Celtic Christianity spread by the Irish mission, and Roman Christianity brought across by Augustine of Canterbury.

Gregorian mission

Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms began in AD 597, influenced by Celtic Christianity from the north-west and by the Roman church from the south-east, gradually replacing Anglo-Saxon polytheism which had been introduced to what is now England over the course of the 5th and 6th centuries with the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons. The first Archbishop of Canterbury, Augustine took office in 597 AD. In 601, he baptized the first Christian Anglo-Saxon king, Æthelberht of Kent. The last pagan Anglo-Saxon/Jutish king, Arwald, died in 686.

Æthelberht of Kent's wife Bertha, daughter of Charibert, one of the Merovingian kings of the Franks, had brought a chaplain (Liudhard) with her. Bertha had restored a church from Roman times to the east of Canterbury and dedicated it to Saint Martin of Tours, the patronal saint for the Merovingian royal family. Æthelberht himself, though a pagan, allowed his wife to worship her God. Probably under influence of his wife, Æthelberht asked Pope Gregory I to send missionaries, and in 596 the Pope dispatched Augustine, together with a party of monks.

Augustine had served as praepositus (prior) of the monastery of Saint Andrew in Rome, founded by Gregory. His party lost heart on the way and Augustine went back to Rome from Provence and asked his superiors to abandon the mission project. The pope, however, commanded and encouraged continuation, and Augustine and his followers landed on the Island of Thanet in the spring of 597.

Æthelberht permitted the missionaries to settle and preach in his town of Canterbury. By the end of the year he himself had converted, and Augustine received consecration as a bishop at Arles. At Christmas 10,000 of the king's subjects underwent baptism.

Augustine sent a report of his success to Pope Gregory with certain questions concerning his work. In 601 Mellitus, Justus and others brought the pope's replies, with the pallium for Augustine and a present of sacred vessels, vestments, relics, books, and the like. Gregory directed the new archbishop to ordain as soon as possible twelve suffragan bishops and to send a bishop to York, who should also have twelve suffragans. Augustine did not carry out this papal plan, nor did he establish the primatial see at London as Gregory intended, as the Londoners remained heathen. Augustine did consecrate Mellitus as bishop of London and Justus as bishop of Rochester.

Pope Gregory issued more practicable mandates concerning heathen temples and usages: he desired that native temples be Christianized and asked Augustine to Christianize pagan practices, so far as possible, into dedication ceremonies or feasts of martyrs, since "he who would climb to a lofty height must go up by steps, not leaps" (letter of Gregory to Mellitus, in Bede, i, 30).

Augustine reconsecrated and rebuilt an old church at Canterbury as his cathedral and founded a monastery in connection with it. He also restored a church and founded the monastery of St. Peter and St. Paul outside the walls. He died before completing the monastery, but now lies buried in the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul.

In 616 Æthelberht of Kent died. The kingdom of Kent and the associated Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which Kent had had influence over relapsed into heathenism for several decades.

Synod of Whitby (664)

The Synod of Whitby in 664 forms a significant watershed in that King Oswiu of Northumbria decided to follow Roman rather than Celtic practices. The spokesman of the dominant faction was St. Wilfrid, who had been much impressed by the power and lavish life style of the Roman Church in comparison with the austerity and subservience to local rulers of the Celtic Church. Using subsidiary arguments about Easter and the tonsure, Wilfrid established the model of the Church as not ultimately answerable to the local king but to the Archbishop and to the Pope. It became a tradition for each Archbishop of Canterbury to receive the pallium from the Pope in Rome. This issue was to be frequently revisited until the Reformation.

Anglo-Saxon mission on the Continent

The Anglo-Saxon mission on the continent took off in the 8th century, assisting the Christianisation of practically all of the Frankish Empire by AD 800.

The Benedictine Movement

The Benedictine reform was led by St. Dunstan over the latter half of the 10th century. It sought to revive church piety by replacing secular canons- often under the direct influence of local landowners, and often their relatives- with celibate monks, answerable to the ecclesiastical hierarchy and ultimately to the Pope. This deeply split England, bringing it to the point of civil war, with the East Anglian nobility (such as Athelstan Half-King, Byrhtnoth) supporting Dunstan and the Wessex aristocracy (Ordgar, Æthelmær the Stout) supporting the secularists. These factions mobilised around King Eadwig (anti-Dunstan) and his brother King Edgar (pro). On the death of Edgar, his son Edward the Martyr was assassinated by the anti-Dunstan faction and their candidate, the young king Æthelred was placed on the throne. However this "most terrible deed since the English came from over the sea" provoked such a revulsion that the secularists climbed down, although Dunstan was effectively retired.

This split fatally weakened the country in the face of renewed Viking attacks.

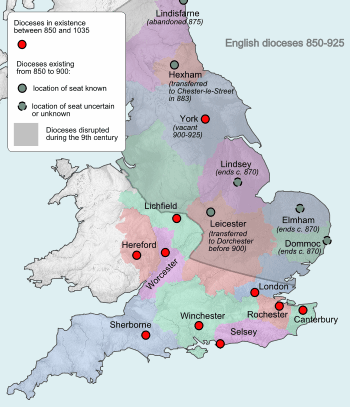

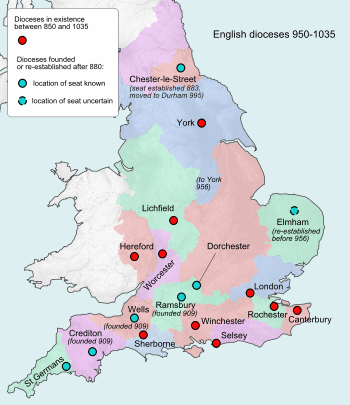

Diocesan organisation

See also

Bibliography

- Chaney, William A. (1960) Paganism to Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England .

- Chaney, William A. (1970). The cult of kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: the transition from paganism to Christianity (Manchester University Press)

- Higham, N. J. (2006) (Re-)Reading Bede: the "Ecclesiastical History" in Context. London: Routledge ISBN 978-0-415-35368-7 ; ISBN 0-415-35367-X

- Mayr-Harting, H. (1991) The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England; 3rd ed., London: Batsford ISBN 0-7134-6589-1

- Thomas, Charles (1981) Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500, London: Batsford

- Yorke, Barbara (2006) The Conversion of Britain, Harlow: Pearson Education

Further reading

- Campbell, James; John, Eric & Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5.

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Rollason, D.W. (1982). The Mildrith Legend: A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England. Atlantic Highlands: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1201-4.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

- Bede Venerablis (1988). A History of the English Church and People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044042-9.

- Blair, John P. (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-921117-5.

- Blair, Peter Hunter; Blair, Peter D. (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53777-0.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury: Christ Church from 597 to 1066. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0041-5.

- Brown, Peter G. (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A. D. 200–1000. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-22138-7.

- Campbell, James (1986). "Observations on the Conversion of England". Essays in Anglo-Saxon History. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 69–84. ISBN 0-907628-32-X.

- Chaney, William A. (1967). "Paganism to Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England". In Thrupp, Sylvia L. Early Medieval Society. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. pp. 67–83.

- Church, S. D. (2008). "Paganism in Conversion-age Anglo-Saxon England: The Evidence of Bede's Ecclesiastical History Reconsidered". History. 93 (310): 162–180. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2008.00420.x.

- Coates, Simon (February 1998). "The Construction of Episcopal Sanctity in early Anglo-Saxon England: the Impact of Venantius Fortunatus". Historical Research. 71 (174): 1–13. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00050.

- Colgrave, Bertram (2007). "Introduction". The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great (Paperback reissue of 1968 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31384-1.

- Collins, Roger (1999). Early Medieval Europe: 300–1000 (Second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-21886-9.

- Dales, Douglas (2005). ""Apostles of the English": Anglo-Saxon Perceptions". L'eredità spirituale di Gregorio Magno tra Occidente e Oriente. Il Segno Gabrielli Editori. ISBN 88-88163-54-9.

- Deanesly, Margaret; Grosjean, Paul (April 1959). "The Canterbury Edition of the Answers of Pope Gregory I to St Augustine". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 10 (1): 1–49. doi:10.1017/S0022046900061832.

- Demacopoulos, George (Fall 2008). "Gregory the Great and the Pagan Shrines of Kent". Journal of Late Antiquity. 1 (2): 353–369. doi:10.1353/jla.0.0018.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1985). Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective (Cornell University Press 1985 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9300-5.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1993). The Pictorial Arts of the West: 800–1200. Pellican History of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06493-4.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1998). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. New York: H. Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-2763-7.

- Foley, W. Trent; Higham, Nicholas. J. (2009). "Bede on the Britons". Early Medieval Europe. 17 (2): 154–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00258.x.

- Frend, William H. C. (2003). Martin Carver, ed. Roman Britain, a Failed Promise. The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 79–92. ISBN 1-84383-125-2.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Gameson, Richard and Fiona (2006). "From Augustine to Parker: The Changing Face of the First Archbishop of Canterbury". In Smyth, Alfred P.; Keynes, Simon. Anglo-Saxons: Studies Presented to Cyril Roy Hart. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 13–38. ISBN 1-85182-932-6.

- Herrin, Judith (1989). The Formation of Christendom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00831-0.

- Higham, N. J. (1997). The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4827-3.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2006). A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1738-5.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Kirby, D. P. (1967). The Making of Early England (Reprint ed.). New York: Schocken Books.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5053-7.

- Jones, Putnam Fennell (July 1928). "The Gregorian Mission and English Education". Speculum (fee required). 3 (3): 335–348. doi:10.2307/2847433.

- Lapidge, Michael (2006). The Anglo-Saxon Library. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926722-7.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). "Laurentius". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lawrence, C. H. (2001). Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-40427-4.

- Markus, R. A. (April 1963). "The Chronology of the Gregorian Mission to England: Bede's Narrative and Gregory's Correspondence". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 14 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1017/S0022046900064356.

- Markus, R. A. (1970). "Gregory the Great and a Papal Missionary Strategy". Studies in Church History 6: The Mission of the Church and the Propagation of the Faith. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–38. OCLC 94815.

- Markus, R. A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58430-2.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00769-9.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (2004). "Augustine (St Augustine) (d. 604)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-03-30. (subscription required)

- McGowan, Joseph P. (2008). "An Introduction to the Corpus of Anglo-Latin Literature". In Philip Pulsiano and Elaine Treharne. A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature (Paperback ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 11–49. ISBN 978-1-4051-7609-5.

- Meens, Rob (1994). "A Background to Augustine's Mission to Anglo-Saxon England". In Lapidge, Michael. Anglo-Saxon England 23. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0-521-47200-5.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2006). "Bertha (b. c.565, d. in or after 601)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-03-30. (subscription required)

- Ortenberg, Veronica (1965). "The Anglo-Saxon Church and the Papacy". In Lawrence, C. H. The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages (1999 reprint ed.). Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 29–62. ISBN 0-7509-1947-7.

- Rumble, A., ed. (2012). Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church: From Bede to Stigand. Boydell and Brewer.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980). "The Decoration of the Leningrad Manuscript of Bede". Selected Papers: Volume 3: Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 199 and 212–214. ISBN 0-7011-2514-4.

- Sisam, Kenneth (January 1956). "Canterbury, Lichfield, and the Vespasian Psalter". Review of English Studies, New series. 7 (25): 1–10. doi:10.1093/res/VII.25.1.

- Spiegel, Flora (2007). "The 'tabernacula' of Gregory the Great and the Conversion of Anglo-Saxon England". Anglo-Saxon England 36. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1017/S0263675107000014.

- "St Augustine Gospels". Grove Dictionary of Art. Art.net. 2000. Accessed on 10 May 2009

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (1998). "Memorializing Gregory the Great: The Origin and Transmission of a Papal Cult in the 7th and early 8th centuries". Early Medieval Europe. 7 (1): 59–84. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00018.

- Walsh, Michael J. (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oates. ISBN 0-86012-438-X.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-56797-8.

- Wilson, David M. (1984). Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to the Norman Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 185807396.

- Wood, Ian (January 1994). "The Mission of Augustine of Canterbury to the English". Speculum (fee required). 69 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2864782. JSTOR 2864782.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-77292-3.