Jutes

The Jutes (/dʒuːts/), Iuti, or Iutæ were a Germanic people. According to Bede,[1] the Jutes were one of the three most powerful Germanic peoples of their time in the Nordic Iron Age,[2][3] the other two being the Saxons and the Angles.[4][5]

The Jutes are believed to have originated from the Jutland Peninsula (called Iutum in Latin) and part of the North Frisian coast. In present times, the Jutlandic Peninsula consists of the mainland of Denmark and Southern Schleswig in Germany. North Frisia is also part of Germany.

The Jutes invaded and settled in southern Britain in the late 4th century during the Age of Migrations, as part of a larger wave of Germanic settlement in the British Isles.

Homeland and historical accounts

Bede places the homeland of the Jutes on the other side of the Angles relative to the Saxons, which would mean the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula. Tacitus portrays a people called the Eudoses living in the north of Jutland and these may have been the later Iutae. The Jutes have also been identified with the Eotenas (ēotenas) involved in the Frisian conflict with the Danes as described in the Finnesburg episode in the poem Beowulf (lines 1068–1159). Others have interpreted the ēotenas as jotuns ("ettins" in English), meaning giants, or as a kenning for "enemies".

Disagreeing with Bede, some historians identify the Jutes with the people called Eucii (or Saxones Eucii), who were evidently associated with the Saxons and dependents of the Franks in 536. The Eucii may have been identical to a little-documented tribe called the Euthiones (Ευθίωνες in Ancient Greek) and probably associated with the Saxons. The Euthiones are mentioned in a poem by Venantius Fortunatus (583) as being under the suzerainty of Chilperic I of the Franks. This identification would agree well with the later location of the Jutes in Kent, since the area just opposite to Kent on the European mainland (present-day Flanders) was part of Francia. Even if Jutes were present to the south of the Saxons in the Rhineland or near the Frisians, this does not contradict the possibility that they were migrants from Jutland.

Another theory, known as the "Jutish hypothesis" – a term accepted by the Oxford English Dictionary – claims that the Jutes may be synonymous with the Geats of southern Sweden or their neighbours, the Gutes. The evidence adduced for this theory includes:

- primary sources referring to the Geats (Geátas) by alternative names such as Iútan, Iótas and Eotas;

- Asser in his Life of Alfred (893) identifies the Jutes with the Goths (in a passage claiming that Alfred the Great was descended, through his mother, Osburga, from the ruling dynasty of the Jutish kingdom of Wihtwara, on the Isle of Wight), and;[6]

- the Gutasaga (13th Century) states that some inhabitants of Gotland left for mainland Europe; large burial sites attributable to either Goths or Gepids were found in the 19th century near Willenberg, Prussia (after 1945 Wielbark in Poland).

However, it is possible that the tribal names were confused in the above sources (an error that demonstrably occurred in sources discussing the death of the 7th Century Swedish king Östen, for example). In both Beowulf (8th – 11th centuries) and Widsith (10th century), the Eotenas (in the Finn passage) are clearly distinguished from the Geatas.

Language

The Germanic dialect which the Jutes spoke is unknown; there is currently no information or credible source to be found on their language. However, it is very likely Jutes had used a traditional Germanic form of the Runic alphabet. Most scholars agree that they spoke either a group of Proto-Norse languages or an Ingvaeonic language, but which dialect of Germanic language was spoken is pure speculation and remains a matter of dispute.

Settlement in southern Britain

The Jutes, along with some Angles, Saxons and Frisians, sailed across the North Sea to raid and eventually invade Great Britain from the late 4th century onwards, either displacing, absorbing, or destroying the native peoples there.

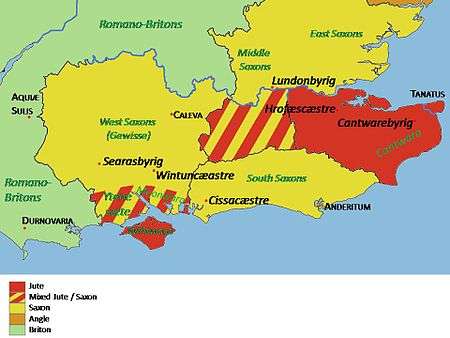

According to Bede, Jutes settled in:

- Kent, where they established Cantaware (Latinised as Cantuarii)

- the Isle of Wight, where they established the kingdom of Wihtwara (Latin: Uictuarii)

- the area known later as Hampshire, where they established the kingdoms of:

- Meonwara (in the Meon Valley area)[7]

- Ytene (which Florence of Worcester states was the name of the area that became the New Forest).

There is also evidence that the Haestingas people who settled in the Hastings area of Sussex, in the 6th century, may also have been Jutish in origin.[8]

While it is commonplace to detect their influences in Kent (for example, the practice of partible inheritance known as gavelkind), the Jutes in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight vanished, probably assimilated to the surrounding Saxons, leaving only the slightest of traces. One recent scholar, Robin Bush, even argued that the Jutes of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight were victims of a form of ethnic cleansing by the West Saxons. Bede clearly implies that this was so, in 686. However, Bush's theory has been the subject of debate amongst academics, including a counter-hypothesis that only the aristocracy were wiped out.[9]

The culture of the Jutes of Kent shows more signs of Roman, Frankish, and Christian influence than that of the Angles or Saxons. Funerary evidence indicates that the pagan practice of cremation ceased relatively early and jewellery recovered from graves has affinities with Rhenish styles from the Continent, perhaps suggesting close commercial connections with Francia. The Quoit Brooch Style has been regarded as Jutish, from the 5th century.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Saxon Invasion British Isles – past and present. IslandGuide.co.uk (by Alan Price)

- ↑ Jutes Channel 4 Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Venerable Saint Bede (1723). The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. John Smith, trans. Printed for T. Batley and T. Meighan.

- ↑ The Germanic invasions of Britain Universität Duisburg-Essen

- ↑ Invaders Historic UK

- ↑ "The British Museum Quarterly". The British Museum. March 1937. pp. 52–54. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Smith, L. (2009). G.E.Jeans, ed. Memorials of Old Hampshire: The Jutish Settlements of the Meon Valley

- ↑ R. Coates. On the alleged Frankish origin of the Hastings tribe in Sussex Archaeological Collections Vol 117. pp. 263-264

- ↑ Time Team, season 9, episode 13 starting at min 21:30 of this video, Bush argues this point with Helen Geake

References

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

External links