Andersonville National Historic Site

|

Andersonville National Historic Site | |

Reconstruction of a section of the stockade wall | |

| |

| Location | Macon / Sumter counties, Georgia, United States |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Andersonville, Georgia, Americus, Georgia |

| Coordinates | 32°11′41″N 84°07′44″W / 32.19469°N 84.12895°WCoordinates: 32°11′41″N 84°07′44″W / 32.19469°N 84.12895°W |

| Area | 514 acres (208 ha)[1] |

| Built | April 1864 |

| Visitation | 1,436,759 (2011)[2] |

| Website | Andersonville National Historic Site |

| NRHP reference # | 70000070[3][4] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 16, 1970 |

| Designated NHS | October 16, 1970 |

The Andersonville National Historic Site, located near Andersonville, Georgia, preserves the former Camp Sumter (also known as Andersonville Prison), a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp during the final twelve months of the American Civil War. Most of the site lies in southwestern Macon County, adjacent to the east side of the town of Andersonville. As well as the former prison, the site contains the Andersonville National Cemetery and the National Prisoner of War Museum. The prison was made in February of 1864 and served to April of 1865.

The site was commanded by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried and executed after the war for war crimes. It was overcrowded to four times its capacity, with an inadequate water supply, inadequate food rations, and unsanitary conditions. Of the approximately 45,000 Union prisoners held at Camp Sumter during the war, nearly 13,000 died. The chief causes of death were scurvy, diarrhea, and dysentery.

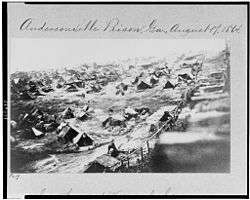

Conditions

The prison, which opened in February 1864,[5] originally covered about 16.5 acres (6.7 ha) of land enclosed by a 15-foot (4.6 m) high stockade. In June 1864, it was enlarged to 26.5 acres (10.7 ha). The stockade was rectangular, of dimensions 1,620 feet (490 m) by 779 feet (237 m). There were two entrances on the west side of the stockade, known as "north entrance" and "south entrance".[6]

Descriptions of Andersonville

Robert H. Kellogg, sergeant major in the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, described his entry as a prisoner into the prison camp, May 2, 1864:

As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. "Can this be hell?" "God protect us!" and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.[7]

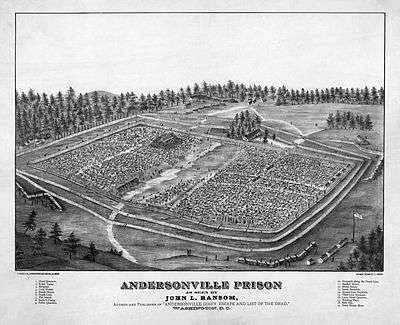

Further descriptions of the camp can be found in the diary of Ransom Chadwick, a member of the 85th New York Infantry Regiment. Chadwick and his regimental mates were taken to the Andersonville Prison, arriving on April 30, 1864.[8] An extensive and detailed diary was kept by John L. Ransom of his time as a prisoner at Andersonville.[9]

Father Peter Whelan arrived on 16 June 1864 to muster the resources of the Catholic church and help provide relief to the prisoners.

The Dead Line

At Andersonville, a light fence known as "the dead line" was erected approximately 19 feet (5.8 m) inside the stockade wall. It demarcated a no-man's land that kept prisoners away from the stockade wall, which was made of rough-hewn logs about 16 feet (4.9 m) high and stakes driven into the ground.[10] Anyone crossing or even touching this "dead line" was shot without warning by sentries in the pigeon roosts.

Health problems

At this stage of the war, Andersonville Prison was frequently undersupplied with food. By 1864, not only civilians living within the Confederacy but also the soldiers of the Confederate Army itself were struggling to obtain sufficient quantities of food. The shortage of fare was suffered by prisoners and Confederate personnel alike within the fort, but the prisoners received less than the guards, who unlike their captives did not become severely emaciated or suffer from scurvy (a consequence of vitamin C deficiency due to a lack of fresh fruits and vegetables in their diet). The latter was likely a major cause of the camp's high mortality rate, as well as dysentery and typhoid fever, which were the result of filthy living conditions and poor sanitation; the only source of drinking water originated from a creek which also served as the camp's latrine, which was filled at all times with fecal matter from thousands of sick and dying men. Even when sufficient quantities of supplies were available, they were of poor quality and inadequately prepared.

There were no new outfits given to prisoners, whose own clothing was often falling to pieces. In some cases, garments were taken from the dead. John McElroy, a prisoner at Andersonville, recalled "Before one was fairly cold his clothes would be appropriated and divided, and I have seen many sharp fights between contesting claimants."[11]

Although the prison was surrounded by forest, very little wood was allowed to the prisoners for warmth or cooking. This, along with the lack of utensils, made it almost impossible for the prisoners to cook the meagre food rations they received, which consisted of poorly milled cornflour. During the summer of 1864, Union prisoners suffered greatly from hunger, exposure and disease. Within seven months, about a third had died from dysentery and scurvy; they were buried in mass graves, the standard practice for Confederate prison authorities at Andersonville. In 1864, the Confederate Surgeon General asked Joseph Jones, an expert on infectious disease, to investigate the high mortality rate at the camp. He concluded that it was due to "scorbutic dysentery" (bloody diarrhea caused by vitamin C deficiency). In 2010, the historian Drisdelle said that hookworm disease, a condition not recognized or known during the Civil War, was the major cause of much of the fatalities amongst the prisoners.[12]

The water supply from Stockade Creek became polluted when too many Union prisoners were housed by the Confederate authorities within the prison walls. Part of the creek was used as a sink, and the men were forced to wash themselves in the creek.

Survival and social networks

At the time of the Civil War, the concept of a prisoner of war camp was still new. It was as late as 1863 when President Lincoln demanded a code of conduct be instituted to guarantee prisoners of war the entitlement to food and medical treatment and to protect them from enslavement, torture, and murder. Andersonville did not provide its occupants with these guarantees; therefore, the prisoners at Andersonville, without any sort of law enforcement or protections, functioned more closely to a primitive society than a civil one. As such, survival often depended on the strength of a prisoner's social network within the prison. A prisoner with friends inside Andersonville was more likely to survive than a lonesome prisoner. Social networks provided prisoners with food, clothes, shelter, moral support, trading opportunities, and protection against other prisoners. One study found that a prisoner having a strong social network within Andersonville "had a statistically significant positive effect on survival probabilities, and that the closer the ties between friends as measured by such identifiers as ethnicity, kinship, and the same hometown, the bigger the effect."[13]

The Raiders

The guards, disease, starvation and exposure were not all that prisoners had to deal with. A group of prisoners, calling themselves the Andersonville Raiders, attacked their fellow inmates to steal food, jewelry, money and clothing. They were armed mostly with clubs and killed to get what they wanted. Another group rose up, organized by Peter "Big Pete" Aubrey, to stop the larceny, calling themselves "Regulators". They caught nearly all of the Raiders, who were tried by the Regulators' judge, Peter McCullough, and jury, selected from a group of new prisoners. This jury, upon finding the Raiders guilty, set punishment that included running the gauntlet, being sent to the stocks, ball and chain, and in six cases, hanging.[14]

The conditions were so poor that in July 1864, Captain Wirz paroled five Union soldiers to deliver a petition signed by the majority of Andersonville's prisoners asking that the Union reinstate prisoner exchanges in order to relieve the overcrowding and allow prisoners to leave these terrible conditions. That request was denied. The Union soldiers, who had sworn to do so, returned to report this to their comrades.[15]

Confederacy's offer to release prisoners

In the latter part of the summer of 1864, the Confederacy offered to conditionally release prisoners if the Union would send ships to retrieve them (Andersonville is inland, with access possible only via rail and road). In the autumn of 1864, after the capture of Atlanta, all the prisoners who were well enough to be moved were sent to Millen, Georgia, and Florence, South Carolina. At Millen, better arrangements prevailed. After General William Tecumseh Sherman began his march to the sea, the prisoners were returned to Andersonville.

During the war, 45,000 prisoners were received at Andersonville prison; of these nearly 13,000 died.[16] The nature and causes of the deaths are a continuing source of controversy among historians. Some contend that the deaths resulted from deliberate Confederate war crimes against Union prisoners, while others state that they resulted from disease promoted by severe overcrowding; the food shortage in the Confederate States; the prison officials' incompetence; and the breakdown of the prisoner exchange system, caused by the Confederacy's refusal to include blacks in the exchanges, thus overfilling the stockade.[17] During the war, disease was the primary cause of death in both armies, suggesting that infectious disease was a chronic problem, due to poor sanitation in regular as well as prison camps.

Prisoner population

| Date | Population |

|---|---|

| April 1, 1864 | 7,160[18] |

| May 5, 1864 | 12,000[19] |

| June 13, 1864 | 20,652[20] |

| June 19, 1864 | 23,942[20] |

| July 18, 1864 | 29,076[21] |

| July 31, 1864 | 31,678[22] |

| August 31, 1864 | 31,693[23] |

Dorence Atwater

A young Union prisoner, Dorence Atwater, was chosen to record the names and numbers of the dead at Andersonville, for the use by the Confederacy and the federal government after the war ended. He believed, correctly, the federal government would never see the list. Therefore, he sat next to Henry Wirz, who was in charge of the prison pen, and secretly kept his own list among other papers. When Atwater was released, he put the list in his bag and took it through the lines without being caught. It was published by the New York Tribune when Horace Greeley, the paper's owner, learned the federal government had refused the list and given Atwater much grief. It was Atwater's opinion that Andersonville's commanding officer was trying to ensure that Union prisoners would be rendered unfit to fight if they survived.[24]

Newell Burch

P.O.W. Newell Burch also recorded Andersonville's decrepit conditions (in his diary). A member of the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry, Burch was captured on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg; he was first imprisoned at Belle Isle in Richmond, Virginia, and then Andersonville. He is credited with being the longest-held Union prisoner of war during the Civil War, surviving a total of 661 days in Confederate hands.[25] His original diary is in the collection of the Dunn County Historical Society in Menomonie, Wisconsin; a mimeographed copy is held by the Wisconsin Historical Society.[26]

Escapes

Planning an escape from this camp was routine among the thousands of prisoners. Most men formed units to burrow out of the camp using tunnels. The locations of the tunnels would aim towards nearby forests fifty feet from the wall. Once out – escape was near impossible due to the poor health of prisoners. Prisoners caught trying to escape were denied rations, chain ganged, or killed. More creative methods were tried including playing dead. The death rate of the camp being around a hundred per day made disposing of bodies a relaxed procedure by the guards. Prisoners would pretend to be dead and carried out to the row of dead bodies outside of the walls. As soon as night fell the men would get up and run. Once Wirz learned of this practice he ordered an examination by surgeons on all bodies taken out of the camp.[27]

Confederate records show that 351 prisoners (about 0.7% of all inmates) escaped, though many were recaptured.[28] The US Army lists 32 as returning to Union lines; of the rest, some likely simply returned to civilian life without notifying the military, while others probably died.[28]

Liberation

Andersonville Prison was liberated in May 1865.[29]

Trial

After the war, Henry Wirz, commandant of the inner stockade at Camp Sumter, was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman.

A number of former prisoners testified about conditions at Andersonville, many accusing Wirz of specific acts of cruelty, for some of which Wirz was not even present in the camp. The court also considered official correspondence from captured Confederate records. Perhaps the most damaging was a letter to the Confederate surgeon general by Dr. James Jones, who in 1864 was sent by Richmond to investigate conditions at Camp Sumter.[30] Jones had been appalled by what he found, and reported he vomited twice and contracted influenza from the single hour he'd toured the camp. His graphically detailed report to his superiors all but closed the case for the prosecution.

Wirz presented evidence that he had pleaded to Confederate authorities to try to get more food and that he had tried to improve the conditions for the prisoners inside.[31][32] However, he was found guilty and was sentenced to death, and on November 10, 1865, he was hanged. Wirz was the only Confederate official to be tried and convicted of war crimes resulting from the Civil War (but see reference to Champ Ferguson). The revelation of the prisoners' sufferings was one of the factors that shaped public opinion in the North regarding the South after the close of the Civil War.

Aftermath

In 1890, the Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Georgia, bought the site of Andersonville Prison through membership and subscriptions.[33] In 1910, the site was donated to the federal government by the Woman's Relief Corps[34] (auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic).[35]

National Prisoner of War Museum

The National Prisoner of War Museum opened in 1998 as a memorial to all American prisoners of war. Exhibits use art, photographs, displays, and video presentations to depict the capture, living conditions, hardships, and experiences of American prisoners of war in all periods. The museum also serves as the park's visitor center.[36]

Andersonville National Cemetery

The cemetery is the final resting place for the Union prisoners who died while being held at Camp Sumter/Andersonville as POWs. The prisoners' burial ground at Camp Sumter has been made a national cemetery. It contains 13,714 graves, of which 921 are marked "unknown".[37]

As a National Cemetery, it is also used as a burial place for more recent veterans and their dependents.[38]

Visitors can walk the 26.5-acre (10.7 ha) site of Camp Sumter, which has been outlined with double rows of white posts. Two sections of the stockade wall have been reconstructed: the north gate and the northeast corner.

Notable monuments and burials

- Medal of Honor recipients:

- Luther H. Story (1931–1950), from nearby Buena Vista, for action in the Korean War, September 1, 1950 (cenotaph)[39]

Depictions in popular culture

- Andersonville (1955) is a novel by MacKinlay Kantor concerning the Andersonville prison. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1956.

- The Andersonville Trial (1970), a PBS television adaptation of a 1959 Broadway play. It depicts the 1865 trial of Andersonville commandant Henry Wirz.

- Andersonville (2015) is a horror/alternate history novel by Edward M. Erdelac, set in the prison.

- The TV movie Andersonville (1996), directed by John Frankenheimer, tells the story of the notorious Confederate prison camp.[40]

- Gene Hackman; Daniel Lenihan (2008). Escape from Andersonville: A Novel of the Civil War. Macmillan. p. 352. ISBN 0-312-36373-7. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- Max R. Terman's Hiram's Honor: Reliving Private Terman's Civil War (2009, Hillsboro, KS: TESA Books, ISBN 0-615-27812-4), is an historical novel.[41]

- In the TV series Hell on Wheels, the villainous character Thor Gundersen is a survivor of Andersonville; his experiences there have left deep mental scars and fuel his hatred of the protagonist, Confederate veteran Cullen Bohannon, the railway foreman. In the depths of his madness, Gundersen begins calling himself "Mr. Anderson".

- This camp is briefly mentioned in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, as Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef) uses it as an excuse to rule his camp with an iron fist. This is one of the most visible historical errors (anachronisms) in the film, since it is set during the New Mexico Campaign, two years before the opening of the prison.

- The novel Inferno, by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, contains a brief reference to the camp; in the novel, set in Hell, Billy the Kid remarks that "the guy who ran the Andersonville prison camp" is being eternally tortured on an island in Phlegethon, the river of boiling blood.

- A novel written in 2014 by Tracy Groot entitled "The Sentinels of Andersonville" depicts some of the Historical players such as Capt. Henry Wirz and General John Winder and fictional prisoners in Andersonville Prison as rebel neighbors, attempting to help the prisoners, were vilified by the town of Americus, GA.

- Stephen Vincent Benet's epic John Brown's Body (poem) refers to Andersonville and Wirz's trial as one of two incidents emblematic of the Civil War POW camps.

- In the seventh episode of Ken Burns's 1990 PBS TV miniseries The Civil War, "1864, Most Hallowed Ground", a segment entitled "Can Those Be Men?" is devoted to Andersonville; its title derives from a quote by Walt Whitman (voiced in the film by Garrison Keillor) which runs in part: "Can those be men? Are they not really corpses?...The dead there are not to be pitied as much as some of the living that come from there - if they can be called living."

Gallery

Some of the monuments at Andersonville

Some of the monuments at Andersonville Bird's eye view

Bird's eye view Memorial Wall

Memorial Wall.jpg) Statue

Statue.jpg) Providence Spring

Providence Spring Providence Spring

Providence Spring star fort

star fort panoramic view of site

panoramic view of site

Andersonville National Cemetery

detail of graves

detail of graves Memorial

Memorial Rostrum

Rostrum Rostrum Interior

Rostrum Interior

See also

- Camp Douglas

- Dix–Hill Cartel, the agreement reached in July 1862 to regulate prisoner of war exchanges

- Elmira Prison

- Florence Stockade

- Immortal Six Hundred

- Libby Prison

- Magnolia Springs State Park (Camp Lawton)

- Salisbury Prison

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Horrors of Andersonvile James K. Polk

- ↑ "Andersonville Civil War Prison Historical Background". 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Pamphlet Andersonville, National Park Service

- ↑ Kellogg, Robert H. Life and Death in Rebel Prisons. Hartford, CT: L. Stebbins, 1865.

- ↑ "Ransom Chadwick: An Inventory of His Andersonville Prison Diary at the Minnesota Historical Society". Mnhs.org. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ↑ https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=wH_hAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg=GBS.PA3

- ↑ Andersonville, Giving Up the Ghost, A Collection of Prisoners' Diaries, Letters and Memoirs by William Stryple

- ↑ The Civil War: A Visual History- Rare Images and Tales of War Between the States. Parragon. 2011. p. 180.

- ↑ Drisdelle R. Parasites. Tales of Humanity's Most Unwelcome Guests. Univ. of California Publishers, 2010. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-520-25938-6.

- ↑ Costa, D.L. (2007). "Surviving andersonville: The benefits of social networks in POW camps". The American Economic Review. 4 (97): 1467–1487. doi:10.1257/aer.97.4.1467.

- ↑ "Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp-Reading 2". Cr.nps.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ↑ Prof. Linder. "Scopes Trial Home Page – UMKC School of Law". Law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ↑ "Camp Sumter / Andersonville Prison". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ↑ Marvel, William, Andersonville: The Last Depot, University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

- ↑ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 169

- ↑ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 119

- 1 2 Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 381

- ↑ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 493

- ↑ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 517

- ↑ Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Volume VII, 1899 p. 708

- ↑ Safranski, Debby Burnett, Angel of Andersonville, Prince of Tahiti: The Extraordinary Life of Dorence Atwater, Alling-Porterfield Publishing House, 2008.

- ↑ Andreas, A.T. (1881). History of Northern Wisconsin, An Account of Its Settlement, Growth, Development and Resources; an Extensive Sketch of its Counties, Cities, Towns and Villages. Chicago: The Western Historical Company via USGenWeb. p. 283.

- ↑ "Plate: front view: Object Description". Wisconsin Decorative Arts Database, Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Andersonville Diary". Brigham Young University .

- 1 2 "Successful Escapes From Andersonville". National Park Service.

- ↑ "Andersonville: Earlier War Crimes "Abuse" Trial | Strike-The-Root: A Journal of Liberty". Strike-The-Root. 2004-05-11. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ↑ A Perfect Picture of Hell: Eyewitness Accounts by Civil War Prisoners from the 12th Iowa, copyright 2001, University of Iowa Press

- ↑ Wirz and Andersonville

- ↑ [Smithsonian]

- ↑ Roster and History of the Department of Georgia (States of Georgia and South Carolina) Grand Army of the Republic, Atlanta, Georgia: Syl. Lester & Co. Printers, 1894, 5.

- ↑ "Andersonville National Historic Site - Park Statistics (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ "WRC National Woman's Relief Corps, Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic, Inc". suvcw.org. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Andersonville National Historic Site – National Prisoner of War Museum (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ Wood, Amy Louise (2011-11-14). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 19: Violence. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807869284.

- ↑ Andersonville National Historic Site. Burial Guidelines and Qualifications. Accessed July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Luther H. Story at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Andersonville (TV 1996) – IMDb". imdb.com. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Andersonville's Whirlpool of Death". Clevelandcivilwarroundtable.com. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

Further reading

Scholarly studies

- Cloyd, Benjamin G. Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory. (Louisiana State University Press, 2010)

- Costa, Dora L; Kahn, Matthew E. "Surviving Andersonville: The Benefits of Social Networks in POW Camps," American Economic Review (2007) 97#4 pp. 1467–1487. econometrics

- Domby, Adam H. "Captives of Memory: The Contested Legacy of Race at Andersonville National Historic Site" Civil War History (2017) 63#3 pp. 253-294 online

- Futch, Ovid. "Prison Life at Andersonville," Civil War History (1962) 8#2 pp. 121–35 in Project MUSE

- Futch, Ovid. History of Andersonville Prison (1968)

- Marvel, William. Andersonville: The Last Depot (University of North Carolina Press, 1994) excerpt and text search

- Pickenpaugh, Roger. Captives in Blue: The Civil War Prisons of the Confederacy (2013) pp. 119–66

- Rhodes, James, History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, vol. V. New York: Macmillan, 1904.

Primary and other sources

- Chipman, Norton P. The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison. San Francisco: Bancroft, 1891.

- Genoways, Ted & Hugh H. Genoways (eds.). A Perfect Picture of Hell: Eyewitness Accounts by Civil War Prisoners from the 12th Iowa. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001.

- McElroy, John. Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons Toledo: D.R. Locke, 1879.

- Ransom, John. Andersonville Diary. Auburn, NY: Author, 1881.

- Ranzan, David, ed. Surviving Andersonville: One Prisoner’s Recollections of the Civil War’s Most Notorious Camp. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2013.

- Spencer, Ambrose. A Narrative of Andersonville. New York: Harper, 1866.

- Stevenson, R. Randolph. The Southern Side, or Andersonville Prison. Baltimore: Turnbull, 1876.

- Voorhees, Alfred H. The Andersonville Prison Diary of Alfred H. Voorhees. 1864.

External links

- Andersonville National Historic Site at NPS.gov – official site

- Andersonville Civil War Prison Historical Background

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Andersonville National Historic Site

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Andersonville National Cemetery

- "WWW Guide to Civil War Prisons" (2004)

- "The Rebel Prison Pen at Andersonville, Georgia" – transcript of an 1874 newspaper article by a former prison guard

- Andersonville National Cemetery at Find a Gravewallace

- Newspaper articles and clippings about the Andersonville Prison at Newspapers.com