Albigensian Crusade

| Albigensian Crusade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||

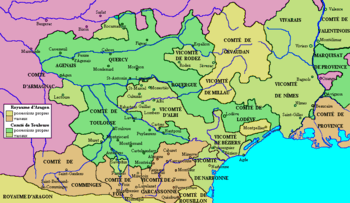

Map of Languedoc on the eve of the Albigensian Crusade | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Cathars | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Simon de Montfort † |

Raymond Roger Trencavel | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 200,000[1] to at most 1,000,000[2] Cathars killed | |||||||

| Considered by many historians to be an act of genocide against the Cathars, including the coiner of the word genocide himself Raphael Lemkin[3][4] | |||||||

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229; French: Croisade des albigeois, Occitan: Crosada dels albigeses) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, in southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crown and promptly took on a genocidal flavour, resulting in not only a significant reduction in the number of practising Cathars, but also a realignment of the County of Toulouse in Languedoc, bringing it into the sphere of the French crown and diminishing the distinct regional culture and high level of influence of the Counts of Barcelona.

The Cathars originated from an anti-materialist reform movement within the Bogomil churches of Dalmatia and Bulgaria calling for a return to the Christian message of perfection, poverty and preaching, combined with a rejection of the physical to the point of starvation. The reforms were a reaction against the often scandalous and dissolute lifestyles of the Catholic clergy in southern France. Their theology, neo-Gnostic in many ways, was basically dualist. Several of their practices, especially their belief in the inherent evil of the physical world, conflicted with the doctrines of the Incarnation of Christ and sacraments, initiated accusations of Gnosticism and brought them the ire of the Catholic establishment. They became known as the Albigensians, because there were many adherents in the city of Albi and the surrounding area in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Between 1022 and 1163, the Cathars were condemned by eight local church councils, the last of which, held at Tours, declared that all Albigenses should be put into prison and have their property confiscated. The Third Lateran Council of 1179 repeated the condemnation. Innocent III's diplomatic attempts to roll back Catharism were met with little success. After the murder of his legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in 1208, Innocent III declared a crusade against the Cathars. He offered the lands of the Cathar heretics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms.

From 1209 to 1215, the Crusaders experienced great success, capturing Cathar lands and perpetrating acts of extreme violence, often against civilians. From 1215 to 1225, a series of revolts caused many of the lands to be lost. A renewed crusade resulted in the recapturing of the territory and effectively drove Catharism underground by 1244. The Albigensian Crusade also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Dominican Order and the Medieval Inquisition. The Dominicans promulgated the message of the Church to combat alleged heresies by preaching the Church's teachings in towns and villages, while the Inquisition investigated heresies. Because of these efforts, by the middle of the 14th century, any discernible traces of the Cathar movement had been eradicated.

Cathar theology

Derived in part from earlier forms of Gnosticism, the theology of the Cathars was dualistic, a belief in two equal and comparable transcendental principles: God, the force of good, and the demiurge, the force of evil. They held that the physical world was evil and created by this demiurge, which they called Rex Mundi (Latin, "King of the World"). Rex Mundi encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful. The Cathar understanding of God was entirely disincarnate: they viewed God as a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the God of love, order, and peace. Jesus was an angel with only a phantom body, and the accounts of him in the New Testament were to be understood allegorically. As the physical world and the human body were the creation of the evil principle, sexual abstinence (even in marriage) was encouraged.[5][6][7] Civil authority had no claim on a Cathar, since this was the rule of the physical world. As such, the Cathars refused to take oaths of allegiance or volunteer for military service.[8] Cathars also refused to kill animals or consume meat.[9][10]

Cathars rejected the Catholic priesthood, labelling its members, including the pope, unworthy and corrupted.[11] Disagreeing on the Catholic concept of the unique role of the priesthood, they taught that anyone, not just the priest, could consecrate the Eucharistic host or hear a confession.[12] Cathars insisted on it being the responsibility of the individual to develop a relationship with God, independent of an established clergy. A particularly prominent 12th-century Cathar preacher was Henry the Petrobrusian, who, in addition to being strongly anti-clerical, adopted the Pelagian view that people were not tainted with original sin, but instead succumbed to sin through their own actions. He gained a large following.[13]

On baptism, Cathars claimed that the sacrament should only be given to adults. Cathars regarded baptism not as a sign of God's grace, to be bestowed on anyone, but as necessitating the conscious decision of an adult.[13] Catharism developed its own unique form of "sacrament" known as the consolamentum, to replace the Catholic rite of baptism. Instead of receiving baptism through water, one received the consolamentum by the laying on of hands.[14][15] They regarded water as unclean because it had been corrupted by the earth, and therefore refused to use it in their ceremonies.[16] The act was typically received just before death, as Cathars believed that this increased one's chances for salvation by wiping away all previous sins.[17] After taking the sacrament, the recipient became known as perfectus.[18]

Despite Cathar anti-clericalism, there were men selected amongst the Cathars to serve as bishops and deacons. The bishops were selected from among the "perfect."[19]

Prelude

By the 12th century, organized groups of dissidents, such as the Waldensians and Cathars, were beginning to appear in the towns and cities of newly urbanized areas. In western Mediterranean France, one of the most urbanized areas of Europe at the time, the Cathars grew to represent a popular mass movement,[20][21] and the belief was spreading to other areas. One such area was Lombardy, which by the 1170s was sustaining a community of Cathars.[22] The Cathar movement was seen by some as a reaction against the corrupt and earthly lifestyles of the clergy. It has also been viewed as a manifestation of dissatisfaction with papal power.[23]

Cathar theology found its greatest success in the Languedoc. The Cathars were known as Albigensians because of their association with the city of Albi, and because the 1176 Church Council which declared the Cathar doctrine heretical was held near Albi.[24] The condemnation was repeated through the Third Lateran Council of 1179.[19] In Languedoc, political control and land ownership was divided among many local lords and heirs.[25][26] Before the crusade, there was little fighting in the area and it had a fairly sophisticated polity. Western Mediterranean France itself was at that time divided between the Crown of Aragon and the County of Toulouse.[27]

On becoming Pope in 1198, Innocent III resolved to deal with the Cathars and sent a delegation of friars to the province of Languedoc to assess the situation. The Cathars of Languedoc were seen as not showing proper respect for the authority of the French king or the local Catholic Church, and their leaders were being protected by powerful nobles,[28] who had clear interest in independence from the king.[29]

One of the most powerful, Count Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, openly supported the Cathars and their independence movement. He refused to assist the delegation. He was excommunicated in May 1207 and an interdict was placed on his lands.[19] Innocent tried to deal with the situation diplomatically by sending a number of preachers, many of them monks of the Cistercian order, to convert the Cathars. They were under the direction of the senior papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau. The preachers managed to bring some people back into the Catholic faith, but for the most part, were renounced.[30] On January 14, 1208, Pierre was killed by one of Raymond's knights. Innocent III claimed that Raymond ordered his execution;[31] William of Tudela blames the murder entirely on "an evil-hearted squire hoping to win the Count's approval".[32]

Pope Innocent declared Raymond anathematized and released all of his subjects from their oaths of obedience to him.[33] However, Raymond soon attempted to reconcile with the Church by sending legates to Rome. They exchanged gifts, reconciled,[34] and the excommunication was lifted. At the Council of Avignon (1209) Raymond was again excommunicated for not fulfilling the conditions of ecclesiastical reconciliation. After this, Innocent III called for a crusade against the Albigensians, with the view that ridding Europe of heresy could better defend its borders against invading Muslims. The time period of the Crusade coincided with the Fifth and Sixth Crusades in the Holy Land.[27]

Military campaigns

Initial success 1209 to 1215

By mid-1209, around 10,000 crusaders had gathered in Lyon before marching south.[35] Many Crusaders stayed on for no more than 40 days before being replaced. A large number came from Northern France,[36] while some had volunteered from England.[37] The crusaders turned towards Montpellier and the lands of Raymond Roger Trencavel, aiming for the Cathar communities around Albi and Carcassonne.[38] Raymond Roger, Raymond's nephew and Count of Foix, was a supporter of the Cathar movement.[39] He initially promised to defend the city of Béziers, but after hearing of the coming of the Crusader army abandoned that city and raced back to Carcassonne to prepare his defences.[38]

Massacre at Béziers

The Crusaders captured the small village of Servian and then headed for Béziers, arriving on July 21, 1209. Under the command of the papal legate, Arnaud Amalric,[40] they started to besiege the city, calling on the Catholics within to come out, and demanding that the Cathars surrender.[41] Neither group did as commanded. The city fell the following day when an abortive sortie was pursued back through the open gates.[42] The entire population was slaughtered and the city burned to the ground. It was reported that Amalric, when asked how to distinguish Cathars from Catholics, responded, "Kill them all! God will know his own." Whether this was actually said is sometimes considered doubtful, but, according to historian Joseph Strayer, it captures the "spirit" of the Crusaders, who killed nearly every man, woman, and child in the town.[43]

Amalric and Milo, a fellow legate, in a letter to the Pope, claimed that the Crusaders "put to the sword almost 20,000 people".[44] Strayer insists that this estimate is too high, but noted that in his letter "the legate expressed no regret about the massacre, not even a word of condolence for the clergy of the cathedral who were killed in front of their own altar".[45] News of the disaster quickly spread and afterwards many settlements surrendered without a fight.[44]

Fall of Carcassonne

After the Massacre at Béziers, the next major target was Carcassonne,[46] a city with many well known Cathars.[47] Carcassonne was well fortified but vulnerable, and overflowing with refugees.[46] The Crusaders traversed the 45 miles between Béziers and Carcassonne in six days,[48] arriving in the city on August 1, 1209. The siege did not last long.[49] By August 7 they had cut the city's water supply. Raymond Roger sought negotiations but was taken prisoner while under truce, and Carcassonne surrendered on August 15. The people were not killed but were forced to leave the town. They were naked according to Peter of Vaux-de-Cernay, a monk and eyewitness to many events of the crusade,[50] but "in their shifts and breeches", according to Guillaume de Puylaurens, a contemporary.[51]

Simon de Montfort, a prominent French nobleman, was then appointed leader of the Crusader army,[52] and was granted control of the area encompassing Carcassonne, Albi, and Béziers. After the fall of Carcassonne, other towns surrendered without a fight. Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Fanjeaux, Limoux, Lombers and Montréal all fell quickly during the autumn.[53]

Lastours and the castle of Cabaret

The next battle centred around Lastours and the adjacent castle of Cabaret. Attacked in December 1209, Pierre Roger de Cabaret repulsed the assault.[54] Fighting largely halted over the winter, but fresh Crusaders arrived.[55] In March 1210, Bram was captured after a short siege.[56] In June the well-fortified city of Minerve was besieged.[57] The city was not of major strategic importance. Simon's decision to attack it was probably influenced by the large number of perfects who had gathered there. Unable to take the town by storm because of the surrounding geography,[58] Simon launched a heavy bombardment against the town, and in late June the main well was destroyed and on July 22, the city, short on water, surrendered.[59] Simon wished to treat the occupants leniently, but was pressured by Arnaud Amalric to punish the Cathars. The Crusaders allowed the soldiers defending the town as well as the Catholics inside of it to go free, along with the non-perfect Cathars. The Cathar "perfects" were given the opportunity to return to Catholicism.[60] Simon and many of his soldiers made strong efforts to convert the Cathar perfects, but were highly unsuccessful.[61] Ultimately, only three women recanted.[60] The 140 who refused were burned at the stake. Some entered the flames voluntarily, not awaiting their executioners.[62]

In August, the Crusade proceeded to the stronghold of Termes.[63] Despite sallies from Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, the siege was solid.[64] The occupants of Termes suffered from a shortage of water, and Raymond agreed to a temporary truce. However, the Cathars were briefly relieved by an intense rainstorm, and so Raymond refused to surrender.[65] Ultimately, the defenders were not able to break the siege, and on November 22 the Cathars managed to abandon the city and escape.[64]

By the time operations resumed in 1211, the actions of Arnaud-Amaury and Simon de Montfort had alienated several important lords, including Raymond de Toulouse,[66] who had been excommunicated again. The Crusaders returned in force to Lastours in March and Pierre-Roger de Cabaret soon agreed to surrender. In May the castle of Aimery de Montréal was retaken; he and his senior knights were hanged, and several hundred Cathars were burned.[67] Cassès fell easily in early June.[68] Afterwards, Simon marched towards Montferrand, where Raymond had placed his brother, Baldwin, in command. After a short siege, Baldwin signed an agreement to abandon the fort in return for swearing an oath to go free and to not fight again against the Crusaders. Baldwin briefly returned to Raymond, but afterward defected to the Crusaders and remained loyal to them thereafter.[69] After taking Montferrand, the Crusaders headed for Toulouse.[70] The town was besieged, but for once the attackers were short of supplies and men, and Simon de Montfort withdrew before the end of the month.[71] Emboldened, Raymond de Toulouse led a force to attack Montfort at Castelnaudary in September.[72] Montfort broke free from the siege[73] but Castelnaudary fell that December to Raymond's troops[74] and Raymond's forces went on to liberate over thirty towns[75] before the counter-attack ground to a halt at Lastours in the autumn.[76]

Toulouse

The Cathars now faced a difficult situation. To repel the Crusaders, they turned to Peter II of Aragon for assistance. A favourite of the Catholic Church, Peter II had been crowned king by Innocent III in 1204. He fought the Moors in Spain, and served in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa.[77] However, his sister, Eleanor, had married Raymond VI, securing an alliance.[78] His victories in the south against the Spanish, along with the persuasion of a delegation sent to Rome, had led Innocent III to order a halt to the crusade. On January 15, 1213, he wrote the legate Arnaud Amaury and to Simon, ordering Simon to restore the lands that he had taken.[79] Concerned also that Simon had grown too powerful,[80] Peter decided to come to the aid of Toulouse.[81] The Crown of Aragon, under Peter II, allied with the County of Toulouse and various other entities.[82] These actions alarmed Innocent, who after hearing from Simon's delegation denounced Peter and ordered a renewal of the crusade.[83] On May 21, he sent Peter a letter severely castigating him for allegedly providing false information, and warning him not to oppose the Crusaders.[84] Peter's coalition force engaged Simon's troops on September 12 in the Battle of Muret. The Crusaders were heavily outnumbered. Peter and Simon both organized their troops into three lines. The first of the Crusader lines was beaten back, but Simon managed to outflank the coalition cavalry. Peter II was struck down and killed. The coalition forces, hearing of his death, retreated in confusion.[82][85] This allowed Simon's troops to occupy the northern part of Toulouse.[86]

It was a serious blow to the resistance, and in 1214 the situation became worse. As the Crusaders continued their advance, Raymond and his son were forced to flee to England,[87] and his lands were given by the Pope to the victorious Philip II, a stratagem which finally succeeded in interesting the king in the conflict. In November, Simon de Montfort entered Périgord[88] and easily captured the castles of Domme[89] and Montfort;[90] he also occupied Castlenaud and destroyed the fortifications of Beynac.[91] In 1215, Castelnaud was recaptured by Montfort,[92] and the Crusaders entered Toulouse.[93] The town paid an indemnity of 30,000 marks.[94] Toulouse was gifted to Montfort.[93] The Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215 solidified Crusader control over the area by officially proclaiming Simon the Count of Toulouse.[95]

Revolts and reverses 1216 to 1225

Raymond VI, together with his son Raymond VII, returned to the region in April 1216 and soon raised a substantial force from disaffected towns. Beaucaire was besieged in May. After three months, the occupants were running low on supplies, and reached an agreement with Raymond to surrender the castle in exchange for being allowed to leave with their arms.[96] The efforts of Montfort to relieve the town were repulsed.[97] Innocent III died suddenly in July 1216[98] and the crusade was left in temporary disarray. The command passed to the more cautious Philip II of France, who was reluctant to vigorously prosecute the crusade.[99] At the time, he was busy fighting a war against King John of England.[100]

Montfort then had to put down an uprising in Toulouse before heading west to capture Bigorre, but he was repulsed at Lourdes in December 1216. On September 12, 1217, Raymond retook Toulouse without a fight while Montfort was occupied in the Foix region. Montfort hurried back, but his forces were insufficient to retake the town before campaigning halted.[97] Responding to a call from Pope Honorius III to renew the crusade,[101] Montfort resumed the siege in the spring of 1218. On June 25[97] or 29,[101] while attempting to fend off a sally by the defenders, Montfort was struck and killed by a stone hurled from defensive siege equipment. Toulouse was held, and the Crusaders driven back. Popular accounts state that the city's artillery was operated by the women and girls of Toulouse.[97]

The Crusade continued with renewed vigour. Philip refused to command in person, but agreed to appoint his son,[102] the also reluctant[103] Prince Louis, to lead an expedition.[102] His army marched south beginning in May, passing through Poitou. In June, an army under Amaury de Montfort,[103] son of the late Simon,[104] joined by Louis, besieged Marmande. The town fell[103] in June 1219. Its occupants, excluding only the commander and his knights, were massacred.[105] After capturing Marmande, Louis attempted to retake Toulouse. Following a siege of six weeks, the army abandoned the mission and went home. Honorius III called the endeavour a "miserable setback". Without Louis's troops, Amaury was unable to hold on to the lands that he had taken, and the Cathars were able to retake much of their land.[106] Castelnaudary was retaken by troops under Raymond VII. Amaury again besieged the town from July 1220 to March 1221, but it withstood an eight-month assault. In 1221, the success of Raymond and his son continued: Montréal and Fanjeaux were retaken and many Catholics were forced to flee. By 1222, Raymond VII had reclaimed all the lands that had been lost. That same year, Raymond VI died and was succeeded by Raymond VII.[107] On July 14, 1223, Philip II died.[108] In 1224, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carcassonne. Raymond VII returned from exile to reclaim the area.[109] That same year, Amaury ceded his remaining lands to Louis VIII.[95]

French royal intervention

In November 1225, the Council of Bourges convened in order to deal with the alleged Cathar heresy. At the council, Raymond VII, like his father, was excommunicated. The council gathered a thousand churchmen to authorize a tax on their annual incomes, the "Albigensian tenth", to support the crusade, though permanent reforms intended to fund the papacy in perpetuity foundered.[110]

Louis VIII headed the new crusade. His army assembled at Bourges in May 1226. While the exact number of troops present is unknown, it was certainly the largest force ever sent against the Cathars.[111] It set out in June 1226.[112] The crusaders captured once more the towns of Béziers, Carcassonne, Beaucaire, and Marseilles, this time with no resistance.[111] However, Avignon, nominally under the rule of the German emperor, did resist, refusing to open its gates to the French troops.[113] Not wanting to storm the well-fortified walls of the town, Louis settled in for a siege. A frontal assault that August was fiercely beaten back. Finally, in early September, the town surrendered, agreeing to pay 6,000 marks and destroy its walls. The town was occupied on September 9. No killing or looting took place.[94] Louis VIII died in November and was succeeded by the child king Louis IX. But Queen-regent Blanche of Castile allowed the crusade to continue under Humbert V de Beaujeu. Labécède fell in 1227 and Vareilles in 1228. At that time, the Crusaders once again besieged Toulouse. While doing so, they systematically laid waste to the surrounding landscape: uprooting vineyards, burning fields and farms, and slaughtering livestock. Eventually, the city was retaken. Raymond did not have the manpower to intervene.[112]

Eventually, Queen Blanche offered Raymond VII a treaty recognizing him as ruler of Toulouse in exchange for his fighting the Cathars, returning all church property, turning over his castles and destroying the defences of Toulouse. Moreover, Raymond had to marry his daughter Joan to Louis' brother Alphonse, with the couple and their heirs obtaining Toulouse after Raymond's death, and the inheritance reverting to the king. Raymond agreed and signed the Treaty of Paris at Meaux on April 12, 1229.[95][114]

Historian Daniel Power notes that the fact that Peter of Vaux-de-Cernay's Historia Albigensis, which many historians of the crusade rely heavily upon, was published only in 1218 leaves a shortage of primary source material for events after that year. As such, there is more difficulty in discerning the nature of various events during the subsequent time period.[37]

Inquisition

The Inquisition was established under Pope Gregory IX in 1234 to uproot heretical movements, including the remaining Cathars. Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it succeeded in crushing Catharism as a popular movement and driving its remaining adherents underground.[115] Punishments for Cathars varied greatly. Most frequently, they were made to wear yellow crosses atop their garments as a sign of outward penance. Others made obligatory pilgrimages, which often included fighting against Muslims. Visiting a local church naked once each month to be scourged was also a common punishment, including for returned pilgrims. Cathars who were slow to repent suffered imprisonment and, often, the loss of property. Others who altogether refused to repent were burned.[116]

The Catholic Church found another useful tool for combating heresy in the establishment of the Order of Preachers, whose members were called "Dominicans", after their founder, Saint Dominic. The Dominicans would travel to towns and villages preaching in favor of the teachings of the Church and against heresy. In some cases, they took part in prosecuting Cathars.[117]

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged by the troops of the seneschal of Carcassonne and Pierre Amiel, the Archbishop of Narbonne.[118] On March 16, 1244, a large massacre took place, in which over 200 Cathar perfects were burnt in an enormous pyre at the prat dels cremats ("field of the burned") near the foot of the castle.[118] After this, Catharism did not completely vanish initially, but was practiced by its remaining adherents in secret.[95]

The Inquisition continued to search for and attempt to prosecute Cathars. While few prominent men joined the Cathars, a small group of ordinary followers remained and were generally successful at concealing themselves. The Inquisitors sometimes used torture as a method to find Cathars,[119] but still were able to catch only a relatively small number.[120] The Inquisitors received funding from the French monarchy up until the 1290s,[119] when King Philip IV, who was in conflict with Pope Boniface VIII, severely restricted it. However, after visiting southern France in 1303, he became alarmed by the anti-monarchical sentiments of the people in the region, especially in Carcassonne, and decided to remove the restrictions placed on the Inquisition.[121]

Pope Clement V introduced new rules designed to protect the rights of the accused.[122] The Dominican Bernard Gui,[123] Inquisitor of Toulouse from 1308 to 1323,[122] wrote a manual discussing the customs of non-Catholic sects and the methods to be employed by the Inquisitors in combating heresy. A large portion of the manual describes the reputed customs of the Cathars, while contrasting them with those of Catholics.[124] Gui also describes methods to be used for interrogating accused Cathars.[125] He ruled that any person found to have died without confessing his known heresy would have his remains exhumed and burned, while any person known to have been a heretic but not known whether to have confessed or not would have his body unearthed but not burned.[126] Under Gui, a final push against Catharism began. By 1350, all known remnants of the movement had been extinguished.[122]

Legacy

Influence

Strayer argues that the Albigensian Crusade increased the power of the French monarchy and made the papacy more dependent on it. This would eventually lead to the Avignon Papacy.[127]

Genocide

Raphael Lemkin, who in the 20th century coined the word "genocide",[128] referred to the Albigensian Crusade as "one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[3] Mark Gregory Pegg writes that "The Albigensian Crusade ushered genocide into the West by linking divine salvation to mass murder, by making slaughter as loving an act as His sacrifice on the cross."[129] Robert E. Lerner argues that Pegg's classification of the Albigensian Crusade as a genocide is inappropriate, on the grounds that it "was proclaimed against unbelievers ... not against a 'genus' or people; those who joined the crusade had no intention of annihilating the population of southern France ... If Pegg wishes to connect the Albigensian Crusade to modern ethnic slaughter, well—words fail me (as they do him)."[130] Laurence Marvin is not as dismissive as Lerner regarding Pegg's contention that the Albigensian Crusade was a genocide; he does, however, take issue with Pegg's argument that the Albigensian Crusade formed an important historical precedent for later genocides including the Holocaust.[131]

Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Solveig Björnson describe the Albigensian Crusade as "the first ideological genocide".[132] Kurt Jonassohn and Frank Chalk (who together founded the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies) include a detailed case study of the Albigensian Crusade in their genocide studies textbook The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies, authored by Strayer and Malise Ruthven.[133]

References

- ↑ Tatz & Higgins 2016, p. 214.

- ↑ Robertson 1902, p. 254.

- 1 2 Lemkin 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Pegg 2008, p. 195.

- ↑ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 303.

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 162–164.

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, pp. 164–166.

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Gui 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Le Roy Ladurie 1978, p. xi.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 59.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 60.

- 1 2 Costen 1997, p. 54.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 67.

- ↑ Gui 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Gui 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ Barber 2014, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 "Catholic Encyclopedia: Albigenses". New Advent. 1910. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ Martin-Chabot 1931–1961 p. 2

- ↑ Costen 1997, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 214.

- ↑ Mosheim 1867, p. 385.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 26.

- ↑ Graham-Leigh 2005, p. 42.

- 1 2 Falk 2010, p. 169.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Graham-Leigh 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ William of Tudela & Anonymous 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 36.

- ↑ William of Tudela & Anonymous 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 84.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 164.

- 1 2 Power 2009, pp. 1047–1085.

- 1 2 Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 88.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 66.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 121.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 89.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 62.

- 1 2 Milo & Arnaud Amalric 2003, p. 128.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 62–63.

- 1 2 Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 65.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 64.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 98.

- ↑ Guillaume de Puylaurens 2003, p. 34.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 101.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 108–113.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 115–140.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 142.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 151.

- ↑ Marvin 2009a, p. 77.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 154.

- 1 2 Strayer 1971, p. 71.

- ↑ J.C.L. Simonde de Sismondi 1973, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 156.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 168.

- 1 2 Costen 1997, p. 132.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 182–185.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 194.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 215.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 233.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 239.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 243.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 253–265.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 273–276, 279.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 83.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 266, 278.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 286–366.

- ↑ Barber 2014, p. 63.

- ↑ Barber 2014, p. 54.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 367–466.

- 1 2 Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 463.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 92.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 401–411.

- ↑ Wolff & Hazard 1969, p. 302.

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 102.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 528–534.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 529.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 530.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 533–534.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 569.

- 1 2 Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, pp. 554–559, 573.

- 1 2 Strayer 1971, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 Lock 2006, p. 165.

- ↑ Peter of les Vaux de Cernay 1998, p. 584.

- 1 2 3 4 Meyer 1879, p. 419.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Pope Innocent III". New Advent. 1910. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 52.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 98.

- 1 2 Nicholson 2004, p. 63.

- 1 2 Costen 1997, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 3 Strayer 1971, p. 117.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 175.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 118.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 119.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 120.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 151.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 122.

- ↑ Kay 2002.

- 1 2 Strayer 1971, p. 130.

- 1 2 Oldenbourg 1961, p. 215.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 136.

- ↑ Sumption 1978, pp. 230–232.

- ↑ Costen 1997, p. 173.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 Sumption 1978, pp. 238–40.

- 1 2 Strayer 1971, p. 159.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 160.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, pp. 162–163.

- 1 2 3 Strayer 1971, p. 162.

- ↑ Murphy, Cullen (2012). "Torturer's Apprentice". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Gui 2006, pp. 35–43.

- ↑ Gui 2006, pp. 43–46.

- ↑ Gui 2006, p. 179.

- ↑ Strayer 1971, p. 174.

- ↑ "Lemkin, Raphael". UN Refugee Agency. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ Pegg 2008, p. 188.

- ↑ Lerner 2010, p. 92.

- ↑ Marvin 2009b, pp. 801–802.

- ↑ Jonassohn & Björnson 1998, p. 50.

- ↑ Chalk & Jonassohn 1990, pp. 114–138.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Barber, Malcolm (2014) [2000]. The Cathars: Christian Dualists in the Middle Ages. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-256613.

- Chalk, Frank Robert; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- Costen, Michael D. (1997). The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4331-X.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Catholic Church. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Falk, Avner (2010). Franks and Saracens: Reality and Fantasy in the Crusades. London, UK: Karnac Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85575-733-2.

- Graham-Leigh, Elaine (2005). The Southern French Nobility and the Albigensian Crusade. Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-84383-129-5.

- Kay, Richard (2002). The Council of Bourges, 1225: A Documentary History. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company.

- Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1978) [1975]. Bray, Barbara, ed. Montaillou: Cathars and Catholics in a French village: 1294–1324. London, UK: Scolar Press. ISBN 0859674037.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2012). Jacobs, Steven Leonard, ed. Lemkin on Genocide. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-4526-5.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24732-2.

- Lerner, Robert E. (2010). "A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom (review)". Common Knowledge. 16 (2).

- Martin-Chabot, Eugène, editor and translator (1931–1961). "La Chanson de la Croisade Albigeoise éditée et traduite". Paris: Les Belles Lettres. His occitan text is in the Livre de Poche (Lettres Gothiques) edition, which uses the Gougaud 1984 translation for its better poetic style.

- Marvin, Laurence W. (2009a). The Occitan War: A Military and Political History of the Albigensian Crusade, 1209–1218. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521123655.

- Marvin, Laurence W. (2009b). "A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom (review)". The Catholic Historical Review. 95 (4). doi:10.1353/cat.0.0546. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- Meyer, Paul (1879). La Chanson de la Croisade Contre les Albigeois Commencée par Guillaume de Tudèle et Continuée par un Poète Anonyme Éditée et Traduite Pour la Societe de L'Histoire de France. Tome Second.

- Mosheim, Johann Lorenz (1867). Murdock, James, ed. Mosheim's Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern. London, UK: William Tegg.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2004). The Crusades. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 087220619X.

- Pegg, Mark Gregory (2008). A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019988371-4.

- Power, Daniel (October 1, 2009). "Who Went on the Albigensian Crusade?". The English Historical Review. 128 (534). doi:10.1093/ehr/cet252. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Jonassohn, Kurt; Björnson, Karin Solveig (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Piscataway, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-2445-3.

- Oldenbourg, Zoe (1961). Massacre at Montsegur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. ISBN 1-84212-428-5.

- Robertson, John M. (1902). A Short History of Christianity. London, UK: Watts & Co.

- J.C.L. Simonde de Sismondi (1973) [1826]. History of the Crusades Against the Albigenses in the Thirteenth Century. New York, NY: AMS Press.

- Strayer, Joseph R. (1971). The Albigensian Crusades. New York, NY: The Dial Press. ISBN 0-472-09476-9.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1978). The Albigensian Crusade. London, England: Faber. ISBN 0-571-11064-9.

- Tatz, Colin Martin; Higgins, Winton (2016). The Magnitude of Genocide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3161-4.

- Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W., eds. (1969). "Chap. VIII: The Albigensian Crusade". The Later Crusades, 1189–1311. II (Second ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-04844-0.

Primary sources

- Peter of les Vaux de Cernay (1998) [1212–1218]. Sibly, W.A.; Sibly, M.D., eds. The History of the Albigensian Crusade: Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay's Historia Albigensis. Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-807-2.

- Gui, Bernard (2006). Shirley, Janet, ed. The Inquisitor's Guide: A Medieval Manual on Heretics. Welwyn Garden City, UK.: Raventhall Books. ISBN 1905043090.

- Guillaume de Puylaurens (2003). Sibly, W.A.; Sibly, M.D., eds. The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath. Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-925-7.

- Milo; Arnaud Amalric (2003). Sibly, W.A.; Sibly, M.D., eds. Report of the legates Milo and Arnaud Amalric to Pope Innocent III on the first few weeks of the Crusade. Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-925-7.

- William of Tudela; Anonymous (2004) [1213]. The Song of the Cathar Wars: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. Translated by Shirley, Janet. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Further reading

- Lippiatt, G.E.M. (2017). Simon V of Montfort and Baronial Government, 1195–1218. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880513-7.

- Mann, Judith (2002). The Trail of Gnosis: A Lucid Exploration of Gnostic Traditions. Gnosis Traditions Press. ISBN 1-4348-1432-7.

- Weis, René (2001). The Story of the Last Cathars' Rebellion Against the Inquisition, 1290–1329. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-027669-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albigensian Crusade. |

- Albigensian Crusade

- The paths of Cathars by the philosopher Yves Maris.

- The English website of the castle of Termes, besieged in 1210

- The Forgotten Kingdom – The Albigensian Crusade – La Capella Reial – Hespèrion XXI, dir. Jordi Savall

- "Traces of the Bogomil Movement in English", Georgi Vassilev. ACADEMIE BULGARE DES SCIENCES. Institut d'etudes balkaniques. Etudes balkaniques, 1994, No 3