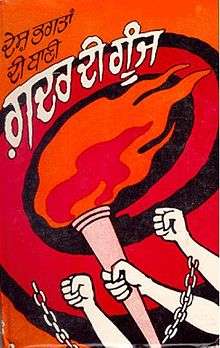

Franz von Papen

| Franz von Papen | |

|---|---|

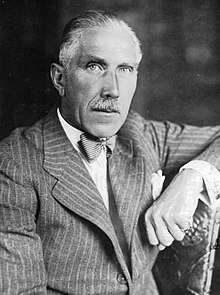

von Papen in 1936 | |

| Chancellor of Germany (Weimar Republic) | |

|

In office 1 June 1932 – 17 November 1932 | |

| President | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Preceded by | Heinrich Brüning |

| Succeeded by | Kurt von Schleicher |

| Vice-Chancellor of the German Reich | |

|

In office 30 January 1933 – 7 August 1934 | |

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Hermann Dietrich |

| Succeeded by | Hermann Göring (1941) |

| Minister President of Prussia | |

|

In office 30 January 1933 – 10 April 1933 | |

| Preceded by | Kurt von Schleicher |

| Succeeded by | Hermann Göring |

|

In office 20 July 1932 – 3 December 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Otto Braun |

| Succeeded by | Kurt von Schleicher |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk 29 October 1879 Werl, Province of Westphalia, German Empire |

| Died |

2 May 1969 (aged 89) Sasbach, Baden-Württemberg, West Germany |

| Resting place | Wallerfangen, Germany |

| Political party |

Zentrum (1918–1932) Independent (1932–1945) |

| Spouse(s) |

Martha von Boch-Galhau (m. 1905; d. 1961) |

| Children |

Friedrich Franz Antoinette Margaretha Isabella Stefanie |

| Alma mater | Prussian Military Academy |

| Profession | Diplomat, military officer |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Rank |

Major Military attaché |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (German: [fɔn ˈpaːpn̩] (![]()

Background

Born into a wealthy and noble Roman Catholic family[1] in Werl, Westphalia, the son of Friedrich von Papen-Köningen (1839–1906) and his wife Anna Laura von Steffens (1852–1939), Papen was trained as an army officer and as a Herrenreiter ("gentleman rider"), a sport Papen very much enjoyed.[2] Papen was proud of his family's having been granted hereditary rights since the 13th century to mine salt at Werl. Papen always believed in the superiority of the aristocracy over commoners.[3] An excellent horseman and a man of much charm, Papen cut a dashing figure and during this time, made the fateful friendship with Kurt von Schleicher.[4] He had married Martha von Boch-Galhau (1880–1961) on 3 May 1905. Papen's wife was the daughter of a wealthy Saarland industrialist whose dowry made him a very rich man.[4] Fluent in both French and English, Papen traveled widely all over Europe, the Middle East and North America.[4]

Papen served for a period as a military attendant in the Kaiser's Palace, before joining the German General Staff in March 1913. Papen was devoted to Wilhelm II, believing that the Kaiser was always right and just, which justified breaking international law, which Papen dismissed as insignificant compared to the greatness of the Kaiser.[5] The most important intellectual influence on the young Papen were the books of General Friedrich von Bernhardi, who wrote war is "not only an integral part of humanity, but the great civilizing influence of the world".[5] Throughout his life, recurring themes of Papen's philosophy were an intense militarism, a belief that Germany had to wage war on others to be great in the Social Darwinian competition of nations, and that "might is right".[5]

He entered the diplomatic service in December 1913 as a military attaché to the German ambassador in the United States. In early 1914 he travelled to Mexico (to which he was also accredited) and observed the Mexican Revolution, returning to Washington, DC in August of that year on the outbreak of the First World War.

In February 1913, General Victoriano Huerta came to power in Mexico by overthrowing President Francisco Madero, who was then "shot while trying to escape", which was the standard euphemism for extrajudicial executions in Mexico. As the United States had imposed an arms embargo on Mexico as Huerta had come to power via a coup, Huerta had to buy arms from Europe and Japan in order to fight the nationwide insurrection that had broken out against his rule in 1913 almost immediately after his coup d'état.[6] Papen supported the idea of selling German arms to Huerta, and was most anxious to go to Mexico City to win Huerta's friendship.[7] Ideas about white supremacy were widely accepted all over the Western world at the time, which led most Westerners to have a dismissive view of the Mexican people as most Mexicans were either Indians or mestizos (of mixed Spanish and Indian descent), and only a minority were Spanish immigrants or their criollo descendants. The Mexican Revolution was viewed at the time in the West in racist terms, as the sort of murderous anarchy that was alleged to result when Indians and mestizos had too much freedom.[8] As a result, all of the European governments backed General Huerta, who attempted to create an intensely militarist regime as the best man to impose the "iron hand" alleged to be needed to "pacify" Mexico.[9] Papen shared these views, reporting to Berlin that Huerta was "the only strong man" in Mexico, who could impose the "iron hand".[10]

During his time in Mexico, Papen differed with ambassador von Hintze about the long-term viability of Huerta's regime with Papen arguing Huerta would prevail provided that he received enough support.[11] At one time, when the anti-Huerta Zapatistas were advancing on Mexico City, Papen organized a group of European volunteers to fight for Huerta.[11] In the spring of 1914, as German military attaché to Mexico, Papen was deeply involved in selling arms to the government of General Huerta, believing he could place Mexico in the German sphere of influence, though the collapse of Huerta's regime in July 1914 ended that hope.[12] In April 1914, Papen personally observed the Battle of Veracruz when the US seized the city of Veracruz, despite orders from Berlin to stay in Mexico City.[13] During his time in Mexico, Papen acquired the love of international intrigue and adventure that was to characterize his later diplomatic postings in the United States, Austria and Turkey.[13]

World War I

On July 30, 1914, Papen arrived in Washington, DC from Mexico to take up his post as German military attaché to the United States.[14] Papen in a statement to the US press declared that Germany was right to invade Belgium despite its treaty commitments to uphold Belgian neutrality, declaring "necessity knows no law", as Papen maintained the invasion of Belgium was an act of "self-defense".[15] Papen tried to buy weapons in the United States for his country, but the British blockade made shipping arms to Germany almost impossible.[16] During the autumn of 1914, while attached to the German Embassy in Washington, DC, Papen's "natural proclivities for intrigue got him involved in espionage activities."[17] On 22 August 1914, Papen hired US private detective Paul Koeing, based in New York City, to conduct a sabotage and bombing campaign against businesses in New York owned by citizens from the Allied nations.[18] Papen knew that agents for the British, French and Russian governments were buying war supplies in the United States, which led Papen, who was given an unlimited fund of cash to draw on by Berlin, to attempt to block such efforts.[16] Papen set up a front company that tried to buy every hydraulic press in the US for the next two years to limit artillery shell production by US firms with contracts with the Allies.[16] To enable German citizens living in the Americas to go home to the Fatherland, Papen set up in New York an operation to forge US passports, with one agent of the Bureau of Investigation who infiltrated the passport mill reporting: "He [Papen] has a list of German reservists in this country, and is in touch with German consulates throughout the country, and in Peru, Chile, Mexico, etc. He communicates with them, and the consuls send the reservists on to New York".[18]

Starting in September 1914, Papen abused his diplomatic immunity (which he enjoyed as German military attaché) and US neutrality to start organising plans for an invasion of Canada, recruiting both German-Americans and Irish-Americans who were to wear a cowboy uniform of Papen's own design to seize Canada in order to force the UK to make peace with Germany on German terms.[19] Papen's inspiration for his plans to invade Canada were the Fenian raids.[20] The Canadian historian Bryon Elson called Papen's plans for invading Canada "farcical".[20] In a prelude to the invasion of Canada, Papen planned on sending men into Canada to sabotage the Welland Canal together with plans to blow up bridges and railroads all over Canada, thereby shutting down the Canadian economy and making it impossible for the Canadians to send troops to Europe.[21] In his reports to Berlin, Papen stated that he gave a US man, a Mr. Bridgeman-Taylor, some $500 to buy explosives to blow up the Welland Canal.[22]

In October 1914, Papen became involved in the Hindu–German Conspiracy, when he contacted anti-British Indian nationalists living in California, and arranged for weapons to be handed over to them.[23] In February 1915, Papen paid a German man Werner Horn $700 to blow up a bridge owned by the Canadian Pacific Railroad in Vanceboro, Maine.[24] Horn was arrested after blowing up the Vanceboro bridge, and the subsequent investigation pointed at Papen as the man responsible, though Papen's diplomatic immunity protected him from arrest.[24] At the same time, Papen was involved in plans to restore the former Mexican President General Victoriano Huerta to power, with Papen arranging for the financing of the planned invasion of Mexico and traveling along the US-Mexican border to find the best invasion routes.[25] After Huerta arrived in New York in May 1915, he met at various times with Papen, Karl Boy-Ed and Franz von Rintelen, each of whom insisted that he alone could speak for Germany.[26]

Papen was able to exclude Rintelen from talking to Huerta, but unknown to him, he was being monitored by the British, who hired a Czech electrician to hide a microphone in the hotel room that Huerta was staying at, allowing them to listen in to all their talks.[26] Papen bought 8,000 rounds of ammunition in St. Louis for the Huertista émigrés and had $800,000 deposited in the Deutsche Bank branch in Havana in an account that Papen had opened up in Huerta's name.[27] Additionally, Papen planned in February–March 1915 to send a New Orleans man named Petersdorf to blow up the oil fields in Tampico, Mexico owned by British oil companies, though the plan was vetoed by the German Navy, which had been able to buy Mexican oil via the Standard Oil company, and felt that a sabotage campaign against Mexican oil fields would strain relations with Mexico too much.[28]

The British historian Donald Cameron Watt wrote that Papen's general incompetence could be seen in that he "… was so careless of his secret documents as to betray to British intelligence most of the activities of the German sabotage ring organized by Captain von Rintelen".[29] One of the documents lost in the briefcase left on a New York tram was a letter that was leaked to the US press where Papen wrote to his wife: "How splendid are things on the Eastern Front. I always say to these idiotic Yankees that they should shut their mouths, or better still, express their admiration for all that heroism".[30] The US press hounded Papen on his "idiotic Yankees" remark, and during a visit to San Francisco, Papen told a journalist that he only meant certain New York newspapers were "idiotic", not the US people in general, claiming that the US media were out to defame him, a statement that only made matters worse for him as any reading of his letter clearly did not support that interpretation.[31] Unknown to Papen, the British had broken the German diplomatic codes, and in late 1915 presented the US government with intercepts of messages showing that Papen had been raising a "legion" for the invasion of Canada; was involved in acts of sabotage and plans for sabotage all over Canada, the United States and Mexico; and sundry other violations of US neutrality.[32]

As a result, some sixteen months into the European War he was expelled from the United States for complicity in the planning of acts of sabotage, such as the Vanceboro international bridge bombing to destroy US rail lines.[33] On 28 December 1915, he was declared persona non grata after his exposure and was recalled to Germany.[34] Setting out on the journey, his luggage was confiscated, and 126 cheque stubs were found showing payments to his agents. Papen went on to report on US attitudes, both to General Erich von Falkenhayn and to Wilhelm II, the German Emperor. Even after returning to Germany, Papen remained involved in plots in the Americas as he contacted in February 1916 the Mexican Colonel Gonzalo Enrile, living in Cuba, in an attempt to arrange German support for Félix Díaz, the would-be strongman of Mexico.[35] Papen arranged for Enrile to go to Berlin in April 1916 to pick up the money he said he needed to make Díaz president, though these plans were derailed when the Germans objected to Enrile's demand that he needed "only" a sum equal to $300 million US in 2016 values to overthrow President Venustiano Carranza.[35] Papen also served as an intermediary between the Irish Volunteers and the German government regarding the purchase and delivery of arms to be used against the British during the Easter Rising of 1916, as well as serving as an intermediary with the Indian nationalists in the Hindu-German Conspiracy. In April 1916, a United States federal grand jury issued an indictment against Papen for a plot to blow up Canada's Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario to Lake Erie, but Papen was by then safely home; he remained under indictment until he became Chancellor of Germany, at which time the charges were dropped.[34] As a Roman Catholic, Papen belonged to the Zentrum, the right of the center party that almost all German Catholics supported, but during the course of the war, the nationalist conservative Papen became estranged from his party.[36] Papen disapproved of Matthias Erzberger, whose efforts to pull the Zentrum to the left, he was opposed to and regarded the Reichstag Peace Resolution of 19 July 1917 as almost treason.[36]

Later in the World War, Papen returned to the army on active service, first on the Western Front. In 1916 Papen took command of the 2nd Reserve Battalion of the 93rd Regiment of the 4th Guards Infantry Division fighting in Flanders.[37] The Guards units of the Prussian Army had the responsibility of protecting Wilhelm II in peacetime, so a posting to a Guards unit was very prestigious. On 22 August 1916 Papen's battalion took heavy losses while successfully resisting a British attack on the river Somme that earned him praise for his courage under fire from his commanders.[38] Between November 1916–February 1917, Papen's battalion was engaged in almost continuous heavy fighting, where Papen displayed coolness under fire and a certain "reckless courage" as he seemed to have no fear of death, but other officers criticized him for his tendency to charge into things without thinking matters through.[39] On 11 April 1917, Papen fought at Vimy Ridge, where his battalion was defeated with heavy losses by the Canadian Corps.[40] The Germans had held Vimy Ridge against repeated French attacks in 1915 and British attacks in 1916, and the ridge become a symbol of German power, so its loss in only one day's fighting to the Canadian corps was considered humiliating. In a report after Vimy, Papen's commanding officers praised him for his courage and elan as he resisted the Canadian assault up the heights of Vimy, ordering counter-attack after counter-attack, but criticised him for poor planning and execution of his counterattacks.[39] Papen argued that the defeat was not so bad as the Canadian Corps were unsuccessful for the previous four weeks in attempting to take Vimy, so its loss in only one day was really not that bad.[39] After Vimy, Papen stated he was tired of commanding infantrymen in defensive battles on the Western Front, and asked for a transfer to the Middle East, where he could fight in offensive battles as a cavalryman, the style of war in which he had been trained, and which suited his personality better.[39] Significantly, Papen's commanding officers were not sorry to lose him, and approved his request to go to the Ottoman Empire.[39]

From June 1917 Papen served as an officer on the General Staff in the Middle East, and then as an officer attached to the Ottoman army in Palestine.[40] During his time in the Ottoman Empire, Papen was in "the know" about the Armenian genocide, which did not appear to have morally troubled him at all either at the time or later in his life.[41] During his time in Constantinople, Papen made another fateful friendship when he befriended Joachim von Ribbentrop. Between October–December 1917, Papen took part in the heavy fighting in Palestine between the German-Ottoman forces under Falkenhayn that were resisting the advance of General Allenby's British-Australian-Indian forces.[42] Papen committed everything he knew to a personal diary, which he kept on his person at all times; during a skirmish at night with British cavalry in Palestine, Papen dropped his diary as he fled, which was found by the British the next morning.[43] Promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, he returned to Germany and left the army soon after the armistice which halted the fighting in November 1918.

After the Ottomans signed an armistice with the Allies on 30 October 1918, the German Asia Corps was ordered home, and Papen was in the mountains at Karapunar when he heard on 11 November 1918 that the war was over.[42] Papen was shocked to hear that his nation had been defeated and his revered monarchy had been toppled, writing "...it was the collapse of every value we had ever known, made even more painful by exile".[44] The new republic ordered soldier's councils to be organized in the German Army, including the Asian corps, which General Otto Liman von Saunders attempted to obey, and which Papen refused to obey.[45] Saunders ordered Papen arrested for his insubordination, which caused Papen to leave his post without permission as he fled to Germany in civilian clothing to personally meet Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, to ask for his help.[46] Hindenburg also disapproved of the soldier's councils, and the charges against Papen were dropped after the latter had explained his story to him.[47]

Inter-war years

The dilettante

After leaving the German Army, Papen purchased a country estate, the Haus Merfeld, living the life of a "gentleman farmer" in Dülmen.[48] In April 1920, during the Communist uprising in the Ruhr, Papen took command of a Freikorps unit to protect Roman Catholicism from the "Red marauders".[49] Impressed with his leadership of his Freikorps unit, the majority of whom were simple farmers, devout in their Catholicism, who instinctively looked to an aristocrat for leadership, Papen decided to pursue a career in politics.[50] In the fall of 1920, the president of the Westphalian Farmer's Association, Baron Engelbert von Kerkerinck zur Borg told Papen his association would campaign for him if he ran for the Prussian Landtag.[51]

Papen entered politics and joined the Centre Party, better known as the Zentrum, in which the monarchist Papen formed part of the conservative wing. Papen belonged to a wing of the Zentrum that was opposed to his party's role as part of the Weimar Coalition, making him very much an outsider in his party.[4] Papen's politics were much closer to the German National People's Party than to the Zentrum, and he seems to have belonged to the Zentrum only on the account of his Roman Catholicism.[4] The German historian Ulrike Ehret called Papen a "fellow traveler" with the Catholic Right, a group of ultra-conservative Catholic intellectuals who rejected democracy, excoriated the Zentrum for working with the SPD, and who were deeply anti-Semitic, but who also rejected the völkisch groups because of their anti-Christian and neo-pagan tendencies.[52] The appeal of the Catholic Right's ideology was especially strong among the Catholic nobility of Westphalia, the social group that Papen himself was a proud member of.[53] Völkisch is an untranslatable German word that literally means populist or folksy, but is perhaps best translated as racialist. While the Catholic Right rejected the völkisch ideology because of its anti-Christian slant, but at the same time saw the völkisch groups as allies in their struggle against the Weimar Republic.[54]

Papen stayed in the Zentrum mostly because he hoped to move his party towards the right, and he often advocated that the Zentrum leave the Weimar Coalition to join a coalition with the German National People's Party.[55] In the words of the British historian Sir John Wheeler-Bennett who lived in Berlin between 1927–34 and knew the "gentleman rider" well, Papen was a "fervent Catholic" who always carried his rosary with him, and was a man of "considerable wealth" as his father-in-law was the richest industrialist in the Saarland.[56] Papen exercised a certain degree of power in the Zentrum by the virtue of being the largest shareholder in the Catholic newspaper Germania, which was the most prestigious of the Catholic papers in Germany.[56] Papen's beliefs were based on a type of Catholic conservatism that believed that sovereignty rested only with God and those He had appointed as His earthly representatives such as the Catholic Church and the aristocracy, which led Papen to a complete rejection of democracy as he felt that sovereignty could not rest with the people.[57] Papen viewed the November Revolution of 1918 as a disaster that had brought "western subjectivism" to Germany, tearing apart the natural order of things and Germany could not recover from this disaster until the democratic system was destroyed.[57] Like many other German Catholic noblemen in the interwar period, Papen had a profound sense of victimization, seeing himself as the victim of a monumental conspiracy.[58] For Papen, European history from the time of the Enlightenment onward was a continuous tale of woe and decline as the "false doctrines" of rationalism, liberalism, republicanism, democracy and secularism had gained ascendancy at the expense of the "true" Catholic and aristocratic values.[58] For Papen, like many Catholic noblemen, the authors of these disastrous developments were the Freemasons and the Jews.[59] For Papen, the present was culmination of all he hated as he saw various developments like Marxism, women's rights, individualism, "economic egoism", democracy and the "de-Christianization" of German culture as part and parcel of the same conspiracy that had allegedly begun in 18th century France.[60]

Papen was a member of the Landtag of Prussia from 1921 to 1928 and from 1930 to 1932, representing a rural, Catholic constituency in Westphalia.[61] Papen rarely attended the sessions of the landtag and never spoke at the meetings during his time as a landtag deputy.[62] Papen tried to have his name entered into the Zentrum party list for the Reichstag elections of May 1924, but was blocked by the Zentrum's leadership who made it clear that they did not want him in the Reichstag, viewing him as a trouble-maker.[63] In February 1925, when Wilhelm Marx of the Zentrum tried to form a coalition government with the SPD in Prussia, Papen was one of the six Zentrum deputies in the landtag who voted with the German National People's Party and the German People's Party against the SPD-Zentrum government.[55] Papen was almost expelled from the Zentrum for breaking with party discipline in the landtag.[55] In the 1925 presidential elections, Papen surprised his party by supporting the right-wing candidate Paul von Hindenburg over Wilhelm Marx. In a 1925 essay, Papen explained his view of Germany:

"The retreat from the universal valid Christian state system since the height of the Middle Ages, the mooring of the present in the principles of a most corrosive subjectivism, the disrespect for divine authority, and the usurpation of the highest state power by the 'sovereign people'-that is the present situation, which one can hardly better describe in one word: parties!"[57]

In the 1925 election, Papen attacked Marx in a press statement as not a proper Catholic for his willingness to work with the Social Democrats.[64] Papen argued that no real Catholic would work with the SPD, whom Papen denounced as a den of "atheistic socialism" and "left-liberal rationalism".[65] In a 1927 article in a Catholic magazine, Papen denounced the Zentrum for accepting the Weimar Republic as he maintained that the constitution of 1919 was based on the "fallacy" that sovereignty rested with the people whereas Papen maintained sovereignty rested only with God and those whom God had entrusted with power.[66] In May 1927 in a speech before a group of Catholic noblemen in Silesia, Papen repeated his Catholic conservative critique of the Weimar Republic as a monstrosity based on the "error" of popular sovereignty and suggested that the remedy was a union of all the German right, saying that in this struggle conservative Catholics would have to work with conservative Protestants against their common "liberal-democratic" foes.[67] In July 1927, in another speech before Catholic aristocrats, this time in Saxony, Papen called for all conservative Catholics to take part in politics, saying that only "the greater participation of the conservatives in the construction of the state" would prevent the triumph of the "liberal-left forces", as he argued that only "the formulation and restoration of a truly conservative weltanschauung on the basis of the teaching of our Holy Church and its revelations in private as well as economic life" could save Germany from the Weimar Republic.[68]

Papen was a member of the exclusive Deutscher Herrenklub (German Gentlemen's Club) of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. Papen, a man largely unknown to the general public, was well known in elite circles in Berlin for his sense of style. This, together with his colorful and much embellished recounting of his adventures in Mexico, the United States, Canada, Flanders, France and the Ottoman Empire in the World War and his capacity to tell a seemingly endless number of jokes, combined to make a much sought after dinner guest among the elite.[69] Most people knew that the more fanciful exploits Papen described were exaggerations, if not fabrications, but Papen was such an entertaining raconteur that few cared. At the Deutscher Herrenklub, Papen would spend hours drinking and talking with his best friend General Kurt von Schleicher who enjoyed his company.[69] Schleicher and his friends liked to call Papen Fränzchen, a somewhat disparaging diminutive of his name Franz, but the French ambassador André François-Poncet who also a member of the Herrenklub noted:"Papen sometimes served as the butt of their jokes; they enjoyed making fun of and teasing him, without him taking the least offense".[69]

Around about 1926, Schleicher came up with the idea of "presidential government" to move Germany back towards a dictatorship by stages via the "25/48/53" formula. The "25/48/53 formula" referred to the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

- Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the Reichstag.[70]

- Article 48 allowed the president to sign emergency bills into law without the consent of the Reichstag. However, the Reichstag could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority vote within sixty days of its passage.[71]

- Article 53 allowed the president to appoint the chancellor.[72]

Schleicher's idea was to have Hindenburg appoint as chancellor a man of Schleicher's choosing, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48.[73] If the Reichstag should threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution.[70] In March 1930, Papen welcomed the coming of presidential government, saying this was the most hopeful sign as yet seen in politics.[74] However, as the presidential government of Heinrich Brüning depended upon the Social Democrats in the Reichstag to "tolerate" it by not voting to cancel laws passed under Article 48, Papen grew more critical.[75] In a speech before a group of farmers in October 1931, Papen called for Brüning to disallow the SPD and base his presidential government on "tolerance" from the NSDAP instead.[76] Papen demanded that Brüning transform the "concealed dictatorship" of a presidential government into a dictatorship that would unite all of the German right under its banner.[77] In the 1932 presidential elections, Papen voted for Hindenburg on the grounds he was the best man to unite the right while in the landtag Papen voted for the Nazi Hans Kerrl who was running to be the speaker of the landtag.[78] In a letter to the editor of the conservative journal Der Ring in April 1932, Papen once again repeated his favorite thesis that the Zentrum would best serve Germany by joining a "genuinely conservative state bloc" that he claimed was emerging in Germany.[79]

Chancellorship

On 28 April 1932, General Kurt von Schleicher met secretly with Adolf Hitler to tell him that the Reichswehr was opposed to the ban imposed on the SA and the SS by Chancellor Heinrich Brüning on 13 April 1932 and he would have it lifted as soon as possible.[80] On 7 May 1932, Schleicher at another secret meeting with Hitler told him that he was working to bring down Brüning and replace him with a new right-wing "presidential government", which Schleicher asked Hitler to support.[80] On 8 May 1932, Hitler and Schleicher reached a "gentleman's agreement" where Schleicher would bring down Brüning, install a new presidential government, lift the ban on the SA and the SS, and would dissolve the Reichstag for elections in the summer of 1932.[81] In exchange, after the elections, Hitler promised to support the new government, whose head Schleicher had not yet selected, and whose purpose Schleicher assured Hitler was the destruction of democracy.[81] After some searching, Schleicher decided his old friend Papen would be the chancellor in the new government he was creating.[82] Papen was not Schleicher's first choice, and it was only after Kuno von Westarp, Alfred Hugenberg, and Carl Friedrich Goerdeler all turned out to be unsuitable for various reasons that Schleicher chose Papen.[82] When a friend warned Schleicher that Papen was regarded as a man with not much of a head, Schleicher replied "He need not have [a head], but he'll make a fine hat!".[83]

On 1 June 1932 Papen moved from relative obscurity to supreme importance when president Paul von Hindenburg appointed him Chancellor, even though this meant replacing his own party's Heinrich Brüning. Papen owed his appointment to the Chancellorship to General Kurt von Schleicher, an old friend from the pre-war General Staff and influential advisor of President Hindenburg. It was Schleicher, not Papen, who selected the new cabinet, in which he also became Defence Minister.[84] The extent that Schleicher was responsible for the Papen government could be seen in that Schleicher had selected the entire cabinet himself before he even had approached Papen with the offer to be chancellor: after Papen had accepted the offer to serve as chancellor, Schleicher simply presented Papen with his list, and told him that this was to be his cabinet.[84] The day before, Papen had promised party chairman Ludwig Kaas he would not accept any appointment. After he broke his pledge, Kaas branded him the "Ephialtes of the Centre Party"; Papen forestalled being expelled from the party by leaving it on 3 June 1932.

The French ambassador in Berlin, André François-Poncet, wrote at the time that Papen's selection by Hindenburg as chancellor was "met with incredulity". "Papen," the ambassador continued, "enjoyed the peculiarity of being taken seriously by neither his friends nor his enemies. He was reputed to be superficial, blundering, untrue, ambitious, vain, crafty and an intriguer."[85] François-Poncet, who knew Papen well thanks to their shared membership in the prestigious Deutscher Herrenklub (German Gentleman's Club) of Berlin, noted that Papen's "face bears the mark of frivolity of which he has never been able to rid himself. As for the rest, he is not regarded as a personality of the first rank...One quality he clearly does possess: cheek, audacity, an amiable audacity of which he seems unaware. He is one of those persons who shouldn't be dared to undertake a dangerous enterprise because they accept all dares, take all bets. If he succeeds, he bursts with pleasure; if he fails, he exits with a pirouette".[61]

The cabinet which Papen formed was known as the "cabinet of barons" or as the "cabinet of monocles"[86] and was widely regarded with ridicule by Germans. Papen had virtually no support in the Reichstag; the only parties committed to supporting him was the far-right/national conservative German National People's Party (DNVP) and German People's Party. However, Papen became very close to Hindenburg. The French Ambassador André François-Poncet reported to his superiors in the Quai d'Orsay about Papen's influence on Hindenburg that "It's he [Papen] who is the preferred one, the favorite of the Marshal; he diverts the old man through his vivacity, his playfulness; he flatters him by showing him respect and devotion; he beguiles him with his daring; he is in [Hindenburg's] eyes the perfect gentleman."[69] Papen first met Hitler in June 1932, and found him a ridiculous figure. Papen always spoke his German with an aristocratic, Westphalian accent and found Hitler with his lower-class Austrian accent of German to be an absurd man, deserving only of contempt.[87] Papen wrote about his meeting with Hitler:

"I found him curiously unimpressive. I could detect no inner quality which might explain his extraordinary hold on the masses. He was wearing a dark blue suit and seemed the complete petit-bourgeois. He had an unhealthy complexion, and with his little moustache and curious hair style had an indefinable bohemian quality. His demeanor was modest and polite, and although I had heard much about the magnetic quality of his eyes, I do not remember being impressed by them...As he talked about his party's aims I was struck by the fanatical insistence with which he presented his arguments. I realized that the fate of my Government would depend to a large extent on the willingness of this man and his followers to back me up, and that this would be the most difficult problem with which I should have to deal. He made it clear that he would not be content with a subordinate role and intended in due course to demand plenary powers for himself. 'I regard your Cabinet only as a temporary solution, and will continue my efforts to make my party the strongest in the country. The Chancellorship will then devolve on me', he said".[88]

The first act of the Papen government was to dissolve the Reichstag in accordance with the "gentlemen's agreement" Schleicher had reached with Hitler on 4 June 1932. As the Nazis had done very well in Länder elections that spring in Oldenburg and Mecklenburg-Schwerin, winning nearly 50% of the vote in both elections, it was reasonably expected by all concerned that the dissolution of the Reichstag only two years into its four-year term would only benefit the National Socialists.[89] As a presidential government, Papen ruled by Article 48, having his emergency decrees signed into law by President Hindenburg and did not seek to govern via the Reichstag.[62] However, the Reichstag could by majority vote cancel any law passed by Article 48 within sixty days of it being signed into law and could pass a vote of no-confidence in the government, which meant that Papen like Brüning before him needed a friendly majority in the Reichstag.[62] As Papen made no secret of his rabid hostility to the Social Democrats and the Zentrum hated him for his role in bringing down Brüning, it was unlikely that the Reichstag elected in 1930 would "tolerate" his government the same way it had the Brüning government.[62] Papen called a national election for July 1932, in the hope that the Nazis would win the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, which would allow him the majority he needed to create a dictatorship.[62] On 15 June 1932, the new government lifted the ban on the SA and the SS, who were secretly encouraged to indulge in as much violence as possible as Schleicher wanted mayhem on the streets to justify the new authoritarian regime he was creating.[90]

On June–July 1932 Papen represented Germany at the Lausanne conference where on 9 July 1932 reparations were cancelled, which Papen followed up by "repudiating" Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles (President Hindenburg had repudiated Article 231 in 1927, a speech that Papen appeared not to be aware of).[91] Speaking at the Lausanne Conference, Papen blamed all of Germany's economic problems on the Treaty of Versailles, saying: "The external debt of Germany, with its very heavy interest charges, is, for the most, attributable to the transfers of capital, and the withdrawals of credits which have been the consequence of the execution of the Treaty of Versailles and of the reparations agreements."[92] During the conference, Papen become famous for his unorthodox style of diplomacy, as he took to speaking frankly to the press about what was going during the conference, which greatly annoyed the other delegates who did not appreciate Papen leaking everything to the media.[93] Papen's intention in leaking so much was to appeal to public opinion in France and the UK by portraying Germany as economically victimized by the Treaty of Versailles as a way of forcing concessions.[93] Papen's tactics failed as he came across as believing that Germany was the only nation in the world suffering from the Great Depression, which did not appeal much to the British and French people who were also suffering. Papen expressed the viewpoint both at the conference table and to the media that Germany was a wronged nation and it was up to France and the UK to make all the concessions, and he should not have to make any compromises.[93]

At a meeting with the French Premier Édouard Herriot on 24 June 1932 during the Lausanne conference, Papen offered him a military alliance, an "economic union" between their nations and a "consultative pact" where both France and Germany would not take action in foreign policy without consulting each other first; in return Papen wanted an end to reparations, the right to "revise" the border with Poland, an Anschluss with Austria, and the end of the military restrictions imposed by Versailles.[94] Herriot was cool to this offer, not the least of which was because Papen took an ultra-nationalist line when addressing German audiences, which led him to doubt Papen's sincerity.[95] Papen leaked his offer to Herriot to a French journalist, which was followed by him saying: "France need have no fear about Germany's good faith because unlike Brüning, I represent all of the national [i.e. conservative] forces of Germany".[96] A number of German conservative newspapers in editorials vigorously denied that Papen spoke for them in making an offer of alliance with France.[96]

Germany had ceased paying reparations in June 1931 under the Hoover moratorium, and most of the groundwork for the Lausanne conference had been done by Brüning, but Papen took all the credit for the Lausanne conference, announcing in a speech that it was his "statesmanship" that had freed Germany from paying reparations to France and repudiated the "war guilt lie" of Article 231.[91] In exchange for cancelling reparations, Germany was supposed to make a one-time payment of 3 million Reichmarks to France, a commitment that Papen repudiated immediately upon his return to Berlin.[91][97] The British historian Anthony Nicolls noted Papen's diplomatic successes did not make Papen popular with the German people at all, which disproves the thesis that it was inflexibility on the part of the Allies in revising the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in Germany's favor that caused the rise of the Nazis.[98]

Papen was authoritarian by inclination. Richard J. Evans described his philosophy as "utopian conservatism" due to his long-term goal of restoring a modern version of the Ancien Régime. He imposed increasingly stringent censorship on the press and repealed his predecessor's ban on the Sturmabteilung (SA) as a way to appease the Nazis, whom he hoped to lure into supporting his government.[99] Papen's economic policies, which were all passed by Article 48, were to sharply cut the payments offered by the unemployment insurance fund, subject all jobless Germans seeking unemployment insurance to a very strict means test, had wages drastically lowered (including those reached by collective bargaining) while bringing in very generous tax cuts to corporations and the rich.[100] Papen argued that lowering taxes on the well off and corporations would encourage them to spend and create jobs; that lowering wages would encourage businesses to hire and reducing unemployment insurance would force the jobless (whom Papen often implied were just lazy people who didn't want to work) to find work; and thus alleviate the effects of the Great Depression.[101] As 1932 was the worst year of the Great Depression with joblessness at an all-time high, Papen's economic policies of favoring the rich while punishing the poor enraged ordinary Germans, making him into Germany's most hated man.[101] Papen reveled in his unpopularity and took a great deal of pleasure in taunting and baiting his critics as he enjoyed provoking people.[102] Papen's thesis that lowering wages would make employers more likely to hire and less likely to fire employees was not a popular one as he was widely viewed as engaging in "one-sided catering" to big business.[103]

The street violence in Germany had largely ceased in the period 13 April-15 June 1932 when the SA and SS had been banned, and it was only after Papen lifted the ban that street violence returned with a vengeance.[104] Riots resulted on the streets of Berlin, as a total of 461 battles between Communists and the SA took place, leading to 82 deaths on both sides. Papen took no responsibility for lifting the ban and blamed the Social Democratic Prussian minister-president Otto Braun for the violence, claiming with no real proof that Braun had ordered the Prussian police to support the Communists against the Nazis.[104] Papen had been looking for a reason to take over Prussia right from the beginning of his Chancellorship, and only held back because he lacked a convincing excuse.[105] On 11 July 1932, with the exception of the Labour Minister Schäffer, the entire cabinet voted to depose the Braun government provided that Papen could find a believable excuse, and on the next day, the Interior Minister Baron Wilhlem von Gayl found that excuse, reporting he heard a rumor that the Social Democrats and Communists were planning a merger.[106] The fact that Social Democrats and Communists were engaging in street battles, which might suggest that this rumor was just that, was disregarded and Papen promptly visited Hindenburg at his estate at Neudeck to ask for and receive a decree allowing the Reich government to take over the Prussian government.[107] In this meeting with Hindenburg, Papen did not talk much about the alleged plans for a SPD-KPD merger, instead saying that the decree was necessary because the Reich and Prussian governments should be headed by the same man as was the case in Imperial Germany.[108] On 20 July 1932, Papen launched a coup against the centre-left coalition government of Prussia, which was dominated by the Social Democrats (the so-called Preußenschlag). The use of the police apparatus in the Prussian "coup" on 20 July 1932 is described by historians Carsten Dams and Michael Stolle as "the decisive breach on the path towards the Third Reich."[109] Berlin was put on military shutdown and Papen sent men to arrest the Prussian authorities, whom he accused with no evidence of being in league with the Communists. Hereafter, Papen declared himself commissioner of Prussia by way of an emergency decree which he elicited from Hindenburg, further weakening the democracy of the Weimar Republic.[110] It was after the Preußenschlag that those Germans who believed in democracy who had been in high spirits in the spring of 1932 began to display a passive, demoralized attitude after Papen's coup as the sense grew that they were playing in a game that was rigged against them.[111]

In Germany, the Reich government made laws, but the Länder governments were responsible for enforcing them as the Reich government had no police force of its own. When Prussia was ruled by Social Democrats, Paragraph 175, which made homosexuality illegal was not enforced as the SPD had long argued for the legalization of homosexuality. With the Preußenschlag, and with Papen serving as the Commissioner for Prussia, this changed as Papen ordered the Prussian police to start enforcing Paragraph 175 and to crack down on "sexual immorality" by banning nude bathing, pornography, and nude dancing together with a law ordering women not to wear "suggestive" clothing in public, though Papen did not ban soliciting by prostitutes as he had promised to.[112] Despite his very acrimonious split with the Zentrum, Papen still had hopes of having the Zentrum support his government, and cracking down on "sexual immorality" in Prussia offered a possible way of winning support from the Catholic church, which supported the Zentrum.[112] But the same time, Papen wished to trade a full scale crackdown in exchange for the Zentrum supporting his government, which explained why Papen's crackdown was not as harsh as many Catholic conservatives would have liked.[113] Papen had hopes in the summer of 1932 of attracting support in the Reichstag of a "black-brown" coalition of the Zentrum and the NSDAP.[114]

In foreign affairs, Papen's principal interest was achieving Gleichberechtigung ("equality of status") as doing away with the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles was known at the World Disarmament Conference, demanding that either Germany be allowed to rearm or the other powers disarm down to the same levels as the Treaty of Versailles had imposed on the Reich (the latter was not a serious demand).[91] On 23 July 1932, Papen had Germany walk out of the World Disarmament Conference following objections from the French delegation that allowing Germany Gleichberechtigung would cause another world war, and Papen announced that the Reich would not return to the conference until the other powers agreed to consider his demand for Gleichberechtigung.[91]

In the Reichstag election of 31 July 1932, the Nazis gained 123 seats, becoming the largest party. Papen expected the Nazis to honor the "gentleman's agreement" by supporting his government and offered Hitler the position of Vice-Chancellor.[115] Hitler however reneged on the "gentleman's agreement" he reached with Schleicher by demanding the Chancellorship for himself.[115] The historian Mary Fulbrook writes that by gaining the largest number of seats in the Reichstag in the elections of 31 July 1932 the Nazis formed "an anti-parliamentary majority not prepared to tolerate the government of von Papen."[116] On 8 August 1932 Papen, who liked to take a tough law-and-order stance, brought in via Article 48 a new law which drastically streamlined the judicial process in death penalty cases while limiting the right of appeal so that the courts could hand down as many death sentences as possible and as many as could be executed as possible.[117] At the time, Papen announced that he expected his new law to be used against "Marxist terrorists"- in the Weimar Republic, the phrase Marxism described both the SPD and the KPD.[118] In an editorial written by Alfred Rosenberg in the Völkischer Beobachter praised Papen for his new law, which Rosenberg called the "beginning towards the annihilation of the red murder banditry".[119] A few hours later in the town of Potempa, five SA men broke into the house of a Communist laborer Konrad Pietrzuch and proceeded to torture, castrate and murder Pietrzuch in front of his mother, launching the cause célèbre of the Potempa Murder of 1932.[117] Pietrzuch was shot twice, stabbed 29 times, and his body had been severely beaten; despite his wounds, Pietrzuch had died as a result of drowning in his blood with the coroner estimating that it took him about half an hour to die.[120] Potempa was a small, ethically mixed village in Silesia located 3 miles from the border with Poland, located in the middle of a vast forest, that was dominated by a feud by a mostly German middle-class who tended to vote Nazi and mostly Polish lower-class who tended to vote Communist, which injected additional venom into Nazi-Communist fighting in the village.[121]

On 11 August 1932, the public holiday of Constitution Day in Germany to celebrate the adoption of the Weimar Constitution in 1919, Papen together with his Interior Minister Baron Wilhelm von Gayl called a press conference, apparently with no sense of the irony involved, to announce their plans for a new constitution which would turn Germany into a dictatorship.[122] On 13 August 1932, Hitler met with Hindenburg to ask be named Chancellor and was refused. Hindenburg told Hitler as recorded by his Chief of Staff Otto Meissner:

"The Reich President in reply said firmly that he must answer this demand with a clear, unyielding "No". He could not justify before God, before his conscience, or before the Fatherland the transfer of the whole authority of government to a single party, especially to a party that was biased against people who had different views from their own. There were a number of other reasons against it, upon which he did not wish to enlarge in detail, such as fear of increased unrest, the effect on foreign countries, etc".[123]

On 22 August 1932 Papen's new law of 8 August (which proscribed the death penalty in all cases of politically motivated murder) was put to the test with "Potempa five" were promptly convicted and sentenced to death, becoming in the process Nazi heroes as Hitler sent them a telegram praising them as great German heroes.[124] Alfred Rosenberg in an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter declared that killing an ethnic Pole like Pietrzuch was no crime as National Socialists like himself rejected the principle that the life of a Pole was equal to the life of a German as National Socialism was based on the belief in the inequality of humanity.[124] The Potempa case generated enormous media attention, and Hitler made it clear that he would not support Papen's government if the "Potempa five" were executed. In an article in the Völkischer Beobachter, Hitler wrote about the Potempa case: "Herr von Papen, I now know your bloody objectivity well...We will liberate the concept of 'national-mindedness' from the clutches of an 'objectivity' whose inner essence sets the judgement of Beuthen against nationalist Germany. Herr von Papen has thereby engraved his name with the blood of national warriors on German history".[125] Ever the Herrenreiter (gentleman rider) confident that he would surmount any obstacle, Papen was not perturbed by this barely veiled threat of violence against himself if the "Potempa five" were executed.[125] On 2 September 1932, Papen in his capacity as Reich Commissioner for Prussia reduced the sentences of the five SA men down to life imprisonment, supposedly because the "Potempa five" were not aware of his law at the time they castrated and murdered Pietrzuch, but in reality because he was hoping for Nazi support of his government.[124] The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw noted that the way in which the National Socialists from Hitler on down praised the "Potempa five" as heroes for torturing, castrating and murdering a man, all because he was a Communist and an ethnic Pole and demanded freedom for the "Potempa five" under the grounds that no German should be punished for killing an ethnic Polish Communist should have been fair warning to Papen and his fellow conservatives about what to expect if Hitler ever became Chancellor.[124]

When the new Reichstag first assembled, Papen hoped to use the opportunity to drop all pretense of democracy. He obtained in advance from Hindenburg a decree to dissolve it, then secured another decree to suspend elections for the time being.[126] When the Reichstag met on 12 September 1932, it managed to elect Hermann Göring as its speaker, which was followed by a Communist motion of no confidence in the Papen government.[127] Papen had anticipated this gambit, however. He knew that the Communist no-confidence motion would only be entertained if the other parties all agreed to a last-minute change in the Reichstag's agenda. Alfred Hugenberg had promised Papen that the DNVP would object to the Communist motion.[127] Hearing reports that the NSDAP and the Zentrum were in talks about forming a new government, Hugenberg ordered the DNVP not to object to the change in agenda without telling Papen as part of an effort to save his government as he believed the Nazis would have to vote against the Communist no-confidence motion to avoid a new election.[128] However, when no one objected, Papen ordered one of his messengers to fetch the dissolution decree. Göring phoned Hitler in Munich, asking him whether the Nazis should vote for the Communist no-confidence motion, and was ordered to vote ja (yes).[129] Papen demanded the floor in order to read the dissolution decree, but Göring pretended not to see him.[130] The motion carried by 512 votes to 42[126]-a result that German historian Eberhard Kolb described as a defeat "such as had never been known in German parliamentary history."[131] Angry and red-faced as Göring ignored him, Papen threw the decree dissolving the Reichstag at him and stormed out.[128] Realizing that he did not have nearly enough support to go through with his plan to subvert the republic from within, Papen decided to call another election to punish the Reichstag for voting against his government.[126] Papen had planned not to call another election after dissolving the Reichstag, but he changed his mind after the NSDAP and the Zentrum threatened to use Article 59 of the constitution, which allowed for impeachment of the president if he violated the constitution, and after Hindenburg's lawyers informed him that dissolving the Reichstag without scheduling new elections was an impeachable offense.[131]

On 1 October 1932, Papen delivered a speech on German radio outlining what his government was attempting to achieve. Papen stated the "enemy of the people" was "cultural bolshevism" which was working to "subvert the spiritual foundation of our existence, loyalty to our people, as well as faith in the eternal truths of Christianity".[132] Papen called for a "conservative policy of renewal" of raising the "supremacy of state power" as the "fundamental error of the enyclopaedists and the liberal era was the proclamation of unlimited freedom of thought, that freedom which destroys before it has constructed anything, that freedom which in molding public opinion reproduces itself daily by the thousands, yet conveys to the people nothing, but the corrosive poison of negative criticism and spiritual abnegation".[133] To which end, Papen called for the creation of the volksgemeinschaft (the "people's community" or "national community") that would unite the German people as one.[134] Papen ended his speech with the call for Christian renewal, saying "The doctrines of Christianity, which have already trained and watched over the European peoples for over a thousand years, and to which the spiritual life of the German people in particular is inextricably bound, are more vital to us today than ever."[135]

Though Schleicher approved of Papen's politics, a certain tension had emerged partly because Papen had proved himself far more aggressive and assertive than Schleicher had expected as the goofy Fränzchen had become a man who saw himself as one of history's Great Men and partly because Schleicher disapproved of Papen's style of provoking ordinary people with the general telling the chancellor that insulting people was not the best way to make them like you.[102] Schleicher wanted the "New State" to enjoy popular legitimacy, and was increasing convinced that Papen's massive unpopularity would denude the "New State" of any legitimacy.[136] On 27 October 1932, the Supreme Court of Germany in a convoluted ruling declared that Papen's coup deposing the Prussian government was illegal as Papen's lawyers had failed to prove his claim that the coup was necessary because the Social Democrats and Communists were allegedly about to merger, but also allowed for Papen to retain his control of Prussia, giving no means for Braun to resume office as the court ruled that the Reich government could depose a Land government if law and order were threatened.[137] In November 1932, Papen showed his contempt for the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by passing an umbau (rebuilding) programme for the German Navy of one aircraft carrier, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, sixteen U-boats and six battleships, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.[138] Versailles had forbidden Germany to have battleships, aircraft carriers and submarines.

In the November 1932 election the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to get a Reichstag that would not pass a vote of no-confidence like the one that brought down his first government.[139] Papen then decided to try to negotiate with Hitler, but Hitler's reply contained so many conditions that Papen gave up all hope of reaching agreement. Hitler wanted a presidential government, but Hindenburg stated that he would allow Hitler a parliamentary government.[139] On 24 November 1932, during the course of another Hitler–Hindenburg meeting, Hindenburg stated his fears that "a presidential cabinet led by Hitler would necessarily develop into a party dictatorship with all its consequences for an extreme aggravation of the conflicts within the German people".[140]Soon afterward, under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on 17 November, and formed a caretaker government. In November 1932, Paul Dinichert, the Swiss ambassador to Germany reported: "I left Herr von Papen with the impression of having spoken with a really glib man who cannot be blamed if one gets bored in his presence. Whether this should be the principal trait of the man who today governs Germany is, to be sure, another question."[61] Konrad Adenauer who knew Papen well often said: "I always gave him the benefit of mitigating circumstances given his enormous limitations."[61]

Papen hoped to be reappointed by Hindenburg, fully expecting that the aging president would find Hitler's demands unacceptable. Indeed, when Schleicher suggested on 1 December that he might be able to get support from the Nazis, Hindenburg blanched and told Papen to try to form another government. Papen told his cabinet that he planned to pursue his "fighting programme" for constitutional and economic reforms even at the risk of civil war, and to circumvent the problem of a hostile Reichstag, which could pass a motion of no-confidence in his government or cancel his laws issued under Article 48, by having martial law declared, which would allow him to rule as a dictator.[139] However, at a cabinet meeting the next day, Papen was informed that there was no way to maintain order against the Nazis and Communists as Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott presented the results of a war games study to the cabinet showing the Reichswehr could not handle the various paramilitary groups if martial law were declared.[136] As Ott was one of Schleicher's closest associates, Papen suspected the war games study had been rigged to suggest that martial law was not an option, an impression reinforced to historians by the fact that a month later in January 1933, Schleicher was to tell Hindenburg that the Reichswehr could easily defeat all of the paramilitary groups if martial law were declared.[141] Realizing that Schleicher was deliberately trying to undercut him, Papen asked Hindenburg to fire Schleicher as defence minister.

Instead, Hindenburg told Papen that he was appointing Schleicher as chancellor. Hindenburg took the loss of Papen very badly, and gave him a present of a picture of himself on which he had written some lines from a song that began with the line "Once I had a comrade".[142] This was unusual as Hindenburg had never given any of the men who served as Chancellor before any sort of gift when they left office.[142] Schleicher hoped to win the support of the Nazis by threatening to create a schism in the Nazi movement that would force Hitler to support him.[143]

Bringing Hitler to power

Papen moved out of the Chancellery, at the request of Hindenburg, into an apartment in the Interior Ministry, which was only divided by the Auswärtige Amt on the Wilhelmstrasse between it and the Chancellery.[144] In the spring of 1932, Hindenburg had moved out of the Presidential Palace, which was in need of repair, and into a wing of the Chancellery.[144] By leaving through the backdoor of the Interior Ministry, Papen could enter the gardens of the Chancellery without being noticed, and took advantage of this to regularly visit Hindenburg, where he attacked Schleicher at every chance.[145] Schleicher had promised Hindenburg that he would never attack Papen in public when he became Chancellor, but in a bid to distance himself from the very unpopular Papen, Schleicher in a series of speeches in December 1932-January 1933 did just that.[144] In Hindenburg's mind, Schleicher—by breaking his word—had not behaved as an officer and a gentleman, which made him miss his favorite Chancellor even more.

Papen was deeply embittered by the way his former best friend, Schleicher, had brought him down, and having acquired a taste for power, Papen was determined to be Chancellor again.[69] On 16 December 1932, Papen delivered a speech before the Herrenklub attacking Schleicher and demanding that the NSDAP be included in the government.[146] Schleicher did not see Papen as a threat at all the Chancellor's Chief of Staff Erwin Planck told a group of journalists: "Let him [Papen] talk, he's completely insignificant. No one takes him seriously. Herr von Papen is a pompous ass. This speech is the swan song of a bad loser".[147] It was Papen who initialed contacts with Hitler as he was consumed, in the words of Kolb, with "wounded ambition and a desire for revenge", becoming full of an obsessive hatred for his former best friend Schleicher.[148] Papen contacted a friend, the Cologne banker Baron Kurt von Schröder who also happened to be a NSDAP member, in late December 1932 to ask him to pass on a message to Hitler saying that Hindenburg's previously warm relations with Schleicher were cooling and that he wanted to meet Hitler to discuss a common strategy against Schleicher.[149] On 4 January 1933, Hitler and Papen met at what was supposed to be a secret meeting at Schröder's house in Cologne.[150] Hitler spent much of the meeting ranting about how he should have been named Chancellor in August 1932 after his party won the largest number of seats in the Reichstag with Papen telling the lie that he had tried to persuade Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor that August, but had been blocked by Schleicher (the opposite was the case).[150] For his part, Papen revealed a marked degree of hatred for Schleicher, with Goebbels writing in his diary afterwards: "He [Papen] wants to bring about his [Schleicher's] fall and get rid of him completely".[150] The principal problem that emerged at the Cologne meeting was the question of who was to be Chancellor, as Papen insisted on having that office for himself whereas Hitler insisted equally vehemently on his "all or nothing" strategy of opposing every government not headed by himself, but the two agreed to keep talking.[151] Papen had strengthened Hitler's hand by revealing to him that Hindenburg had not given Schleicher a decree dissolving the Reichstag nor was likely to do so, which meant when the Reichstag met after its Christmas break on 31 January 1933, it would be possible to bring a vote of no confidence against Schleicher without worrying about new elections.[152]

Before the meeting in Cologne, Papen and Hitler had been photographed going into Schröder's house and the next day 5 January 1933 the news of the Hitler-Papen summit was front-page news all over Germany.[153] Schleicher did not regard the Papen-Hitler talks as a threat, regarding Papen as a silly and foolish man unable to accomplish anything.[154] On 9 January 1933, Papen met with Hindenburg to tell him that he believed that Hitler was now willing to support a presidential government headed by himself.[155] That same day, Papen met with Schleicher to tell him that he had only been seeking to have Hitler support his government at the Cologne meeting, and furthermore he had was not angry about being ousted by him or Schleicher's attacks on him in public.[156] Based on what Papen had told him, Schleicher now believed Hitler was now only seeking to be the defense or interior minister in his government.[157] To continue the talks which started in Cologne, it was decided that henceforth that Papen and Hitler would meet at the house of Joachim von Ribbentrop in Berlin as Ribbentrop was a Nazi who was also an old friend of Papen's going back to their service together in the Ottoman Empire in 1917-18.[158]

The British ambassador Sir Horace Rumbold who met Papen in early January 1933 expressed "the wonder of an observer that the destinies of this great country should have been, even for a short time, in the hands of such a lightweight", commenting that everything Papen had to say was superficial in the extreme and that Papen seemed incapable of critical thinking.[61] Hindenburg told Papen "personally and in strict confidence" that he had his support in attempting to form a new government that would bring in Hitler.[159] As it became increasingly obvious that Schleicher would be unsuccessful in his maneuvering to maintain his chancellorship that would not be defeated by a vote of no-confidence, Papen worked to undermine Schleicher. On 18 January, Papen had lunch at Ribbentrop's house with Hitler, Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Röhm where Hitler argued that because the Nazis had done well in a Lander election in Lippe on 15 January that it would be impossible for him to serve as Vice-Chancellor in another government headed by Papen.[160] When Papen replied that he did not have enough influence with Hindenburg to have Hitler appointed as Chancellor, and he would have to settle for being Vice-Chancellor, Hitler stated that he would stick to his "all or nothing" strategy even if it meant the ruin of the Nazi Party.[161]

On 20 January 1933, Papen met with Otto Meissner, Hindenburg's chief of staff, and Major Oskar von Hindenburg, Hindenburg's son who enjoyed much power by controlling access to his father, to tell them he was considering abandoning his claim for the Chancellorship, and instead was considering the idea of a Hitler chancellorship with himself dominating the government.[162] Papen wanted to know if Meissner and the younger Hindenburg would support such an arrangement and if could they persuade the president to accept Hitler as Chancellor and Papen as Vice-Chancellor.[162] On the evening of 22 January 1933, during a meeting at Ribbentrop's house, Papen seeing that Hitler would not budge from his "all or nothing" stance, made the concession of abandoning his claim to the Chancellorship and promised to support Hitler as Chancellor in the proposed "Government of National Concentration".[162] Along with DNVP leader Alfred Hugenberg, Papen formed an agreement with Hitler under which the Nazi leader would become Chancellor of a coalition government with the Nationalists, with Papen serving as Vice-Chancellor and Minister President of Prussia. On 23 January 1933, Papen first told Hindenburg of his plans to have Hitler as Chancellor while "boxing" him in, which the president objected to.[163] Papen's major problem turned out to be that Hindenburg wanted him to be Chancellor again, and it required much of Papen's powers of persuasion to convince the president that Hitler should be Chancellor instead of himself.[164][165] Adenauer noted about Papen that "matters of principle never interested him" while the scholar Moritz Bonn who knew Papen called him "probably one of the most consummate liars who ever lived".[166]

On 23 January 1933 Schleicher admitted to Hindenburg that he had been unable to prevent a vote of no-confidence from the Reichstag when it was due to convene on 31 January, and asked the president to declare a state of emergency. By this time, the Junker Hindenburg had become irritated by the Schleicher cabinet's policies affecting the Junkers, being enraged that Schleicher had dithered on the question of raising tariffs instead of raising tariffs as he wanted.[167] The Junkers favored a policy of protectionism to keep their estates in business, and Schleicher had been unable to make up his mind if he wanted a policy of free trade that would have pleased industrialists who wanted access to foreign markets or a policy of protectionism which would have pleased the Junkers.[168] Simultaneously, Papen had been working behind the scenes and used his personal friendship with Hindenburg to assure the president that he, Papen, could control Hitler and could thus finally form a government that would not be defeated on a vote of no confidence from the Reichstag, as his government had suffered in September 1932.

Hindenburg refused to grant Schleicher the emergency powers he sought, and Schleicher resigned on 28 January. On the evening of 28 January, Papen met with Hindenburg to tell him that Hitler was moderating his demands, and that most of the men who served in the Schleicher cabinet were willing to serve in a Hitler cabinet.[169] Papen stated he would serve as Vice-Chancellor and Hindenburg told him that he wanted Baron Konstantin von Neurath to remain as Foreign Minister and General Werner von Blomberg to be appointed as Defense Minister as his conditions for a Hitler government.[169] Though Hindenburg did not give his explicit approval to Papen about having Hitler as Chancellor, Papen noted that Hindenburg's demands that Neurath and Blomberg serve in a Hitler cabinet was an important sign that Hindenburg was coming around to accepting Hitler as Chancellor.[169]

In the morning of 29 January, Papen met with Hitler and Hermann Göring at his apartment, where it was agreed that Wilhelm Frick would become Reich Interior Minister and Göring Prussian Interior Minister; in exchange Papen was to serve as Vice-Chancellor and Commissioner for Prussia.[170] It was during the same meeting that Papen first learned that Hitler wanted to dissolve the current Reichstag when he became Chancellor and once the Nazis won a majority of the seats in the ensuing elections to activate the Enabling Act.[171] In the afternoon of that day, Papen had Alfred Hugenberg, Franz Seldte and Theodor Duesterberg over to his apartment to ask for their support.[172] Papen told Hugenberg that he was to be given both the economics and agriculture ministries in the Reich and Prussian governments, fulfilling Hugenberg's long-standing wish to be "economic dictator".[172] Having the DNVP participate in the Hitler government both assuaged Hindenburg's fears about what Hitler might do and increased the number of votes in the Reichstag for the Enabling Act, though Papen did not tell Hugenberg about Hitler's plans for an early election or to pass the Enabling Act as he knew Hugenberg would object.[172] Seldte was won over by a promise that he would serve as labor minister, but Düsterberg objected to Hitler as Chancellor.[172] However, Düsterberg was opposed to democracy, and wanted another presidential government headed by Papen, a course that Papen now rejected, and so Seldte and Hugenberg pressured Düsterberg into going along with a Hitler cabinet after all.[173]

On the evening of 29 January 1933, when the conservative Junker Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin told Papen that his plan to have Hitler as Chancellor while retaining power for himself was an absurd scheme that could only end very badly for everybody, Papen replied: "What do you want? I have the confidence of Hindenburg. In two months we'll have pushed Hitler so far into the corner that he'll squeal."[174] In the end, the President, who had previously vowed never to allow Hitler (whom he derisively referred to as a 'Bohemian corporal'), to become Chancellor, appointed Hitler to the post on 30 January 1933, with Papen as Vice-Chancellor.[175] The British historian Edgar Feuchtwanger wrote that Schleicher's rapid rise and fall from power was due to the system of presidential government he had created in 1930, as the system of presidential government reduced almost everything down to the whims of President Hindenburg, and gave enormous power to those like Papen who happened to enjoy Hindenburg's trust and favor.[176] The system of presidential government created very personalized politics where those who had the approval of Hindenburg and his Kamarilla enjoyed power and those who did not were excluded from power, regardless of what the voters felt.[177] On institutional grounds, Papen should have been in a weak position as he was a very unpopular former Chancellor without a seat in the Reichstag or even a political party, whose influence was based entirely on his friendship with Hindenburg. Feuchwanger wrote that Papen was a vain, irresponsible intriguer who was only powerful in January 1933 because he was Hindenburg's favorite politician and the president wanted his favorite back into office again.[178]

At the formation of Hitler's cabinet on 30 January, only three Nazis had cabinet posts: Hitler, Göring, and Wilhelm Frick. The only Nazi besides Hitler to have an actual portfolio was Frick, who held the then-powerless interior ministry. The other eight posts were held by conservatives close to Papen. Additionally, as part of the deal that allowed Hitler to become Chancellor, Papen was granted the right to attend every meeting between Hitler and Hindenburg. Under the Weimar Constitution, the Chancellor was a fairly weak figure, serving as little more than a chairman. Moreover, Cabinet decisions were made by majority vote. Papen believed that his conservative friends' majority in the Cabinet and his closeness to Hindenburg would keep Hitler in check. To the warning that he was placing himself in Hitler's hands, Papen replied, "You are mistaken. We've hired him."[179] On the morning of 30 January 1933, when Hitler was due to be sworn in as Chancellor by Hindenburg, the "Government of National Concentration" almost collapsed before it began when Hugenberg learned that Hitler planned on dissolving the Reichstag to allow him to get the two-third majority so he could pass the Enabling Act, whereas Hugenberg had been given to believe that the "Government of National Concentration" would rule with the Reichstag elected in November 1932.[180] Passing the Enabling Act would allow Hitler to rule via decree, which would mean that Hitler would not need the support of the DNVP in the Reichstag anymore. Hugenberg knew Hitler well enough to understand what Hitler ruling with the Enabling Act would mean for the DNVP. The discovery that Hitler planned on dissolving the Reichstag caused a lengthy shouting march between Hitler and Hugenberg that delayed the swearing of the Hitler government and was ended when Papen told Hugenberg not to doubt the word of a fellow German and Meissner came out to say Hindenburg was tiring of waiting to swear in the new government.[181] In his 1996 book Hitler's Thirty Days to Power, the US historian Henry Ashby Turner wrote that Papen was "the key figure in steering the course of events toward the disastrous outcome, the person who more than anyone else caused what happened. None of what occurred in January 1933 would have been possible in the absence of his quest for revenge against Schleicher and his hunger for a return to power".[182]

Vice-Chancellor

Hitler and his allies instead quickly marginalized Papen and the rest of the cabinet. For example, as part of the deal between Hitler and Papen, Göring had been appointed interior minister of Prussia, thus putting the largest police force in Germany under Nazi control. He frequently acted without consulting his nominal superior, Papen. The US historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote about the conservative majority of the first Hitler cabinet in 1933 "...that the incredibly low intellectual and political level of most of those who thought they might restrain Hitler by serving in the same cabinet with him rarely put Hitler's abilities to any severe test".[183]

On 1 February 1933, Hitler presented to the cabinet an Article 48 decree law that had been drafted by Papen in November 1932 allowing the police to take people into "protective custody" without charges. It was signed into law by Hindenburg on 4 February as the "Decree for the Protection of the German People".[184] Hitler's first speech on the radio, delivered on 7:00 pm on 1 February 1933 entitled "The appeal of the Reich Government to the German People" was partly written by Papen as the speech praised the need to protect the family and Christianity from "Marxism".[185] However, Papen disapproved of the parts of the speech that called for "two big four-year plans" to end the Great Depression as it "smacked of Soviet methods" to him.[185] On the evening of 27 February 1933, Papen joined Hitler, Göring and Goebbels at the burning Reichstag and told him that he shared their belief that this was the signal for Communist revolution.[186] On 18 March 1933, in his capacity as Reich Commissioner for Prussia, Papen freed the "Potempa Five" whose death sentences he had commuted to life imprisonment in September 1932, under the grounds the murder of Konrad Pietzuch was an act of self-defense, making the five SA "innocent victims" of a miscarriage of justice.[187]