Adullam

| Khirbat esh-Sheikh Madkur / ʿAīd el Mâ | |

Pine-covered hill of Adullam, seen from northwest | |

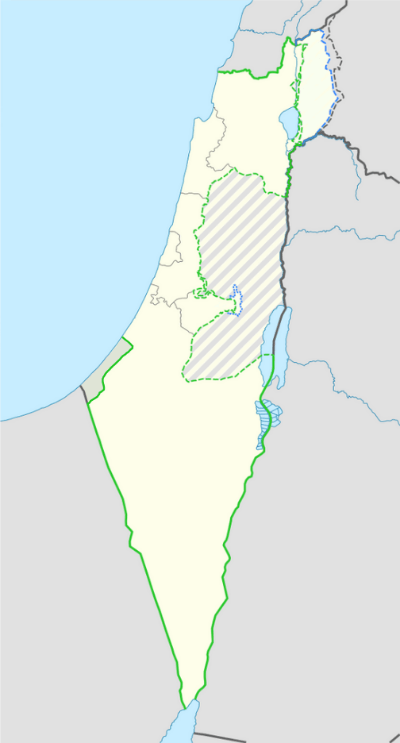

Shown within Israel | |

| Alternative name | 'Eîd el Mieh (Kh. ‘Id el-Minya) |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Region | Shefeleh |

| Coordinates | 31°39′40″N 34°58′40″E / 31.66111°N 34.97778°ECoordinates: 31°39′40″N 34°58′40″E / 31.66111°N 34.97778°E |

| History | |

| Founded | Canaanite period |

| Abandoned | unknown |

| Periods | Early Bronze, Chalcolithic period to the Ottoman period |

| Cultures | Canaanite, Jewish, Greco-Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic, Ottoman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1992, 1999, 2015 |

| Archaeologists | Y. Dagan, B. Zissu, I. Radashkovsky and E. Liraz |

| Condition | Ruin |

| Public access | yes |

Adullam (Hebrew: עֲדֻלָּם) is an ancient ruin, formerly known by the Arabic appellation ʿAīd el Mâ (or `Eîd el Mieh), built upon a hilltop overlooking the Elah Valley, south of Bet Shemesh in Israel. In the late 19th century, the town was still in ruins.[1] The hilltop ruin is also known by the name Khurbet esh-Sheikh Madkour, named after Madkour, one of the sons of the Sultan Beder, for whom is built a shrine (wely) and formerly called by its inhabitants Wely Madkour.[2] The hilltop is mostly flat, with cisterns carved into the rock. The remains of stone structures which once stood there can still be seen. Sedimentary layers of ruins from the old Canaanite and Israelite eras, mostly potsherds, are noticeable everywhere, although olive groves now grow atop of this hill, enclosed within stone hedges. The villages of Aderet, Neve Michael/Roglit, and Aviezer are located nearby. Access to the site may be obtained by passing through the cooperative small holders' agricultural villages (Moshavim) of Aderet or Neve Michael (known also as Roglit). The ruin lies about 3 kilometers south of Moshav Neve Michael.

History

Biblical era

The "Adullam" mentioned in the Hebrew Bible is usually thought to be identical with Tell Sheikh Madkhur, that is, the archaeological ruin referred to in this article as "Adullam."[3][4]

Adullam was one of the royal cities of the Canaanites[5] referred to in the Hebrew Bible. Although listed in Joshua as being a city in the plain, it is actually partly in the hill country, partly in the plain. It stood near the highway which later became the Roman road in the Valley of Elah, the scene of David's victory over Goliath.[6] It was here that Judah, the son of Jacob (Israel), came when he left his father and brothers in Migdal Eder, where he befriended a certain Hirah, an Adullamite,[7] and where he met his first wife (unnamed in Genesis), the daughter of Shua. It was one of the towns which Rehoboam fortified against Egypt.[8] Micah calls it "the glory of Israel."[9]

King David sought refuge in Adullam after being expelled from the city of Gath by King Achish. I Samuel refers to the Cave of Adullam where he found protection while living as a refugee from King Saul. It was there that "every one that was in distress gathered together, and every one that was in debt, and every one that was discontented."[10] Certain caves, grottos and sepulchres are still to be seen on the hilltop, as well as on its northern and eastern slopes.

It was in Adullam that Judas Maccabaeus retired with his fighting men, after returning from war against the Idumaeans.[11] As late as the early 4th century CE, Adullam was described by Eusebius as being "a very large village about ten [Roman] miles east of Eleutheropolis."[12]

Ottoman era

Adullam was an inhabited village in the late 16th-century. An Ottoman tax ledger of 1596 lists `Ayn al-Mayyā (Arabic: عين الميا) in the nahiya Ḫalīl (Hebron subdistrict), and where it is noted that it had in 1596 thirty-six Muslim heads of households.[13] The copyist of the same tax ledger had erroneously mistaken the Arabic dal in the document for a nun, and which name has since been corrected by historical geographers Yoel Elitzur and Toledano to read A'ïd el-Miah (Arabic: عيد الميا), based on the entry's number of fiscal unit in the daftar and its corresponding place on Hütteroth's map.[14][15] The Arabic name, being a corruption of Adullam, is a product of popular etymology.

In the late 19th century, the hilltop ruin and its adjacent ruins were explored by French explorer, Victor Guérin, who wrote:

[Upon leaving the hilltop ruin, Khirbet el-Sheikh Madkour], at 11:20 [AM], we descend to the east in the valley. At 11:25 [AM], I examine other ruins, called Khirbet A'id el-Miah. Sixty toppled houses in the wadi formed a village that still existed in the Muslim period, as [proven by] the remains of a mosque there observed. In antiquity, the ruins that cover the plateau of the hill of Sheikh Madkour and which extend in the valley were probably one and the same city, divided into two parts, the upper part and the lower part.[16]

According to Conder, an ancient road, leading from Beit Sur to Ashdod, once passed through ʿAīd el Mâ (Adullam).[17]

French orientalist and archaeologist, Charles Clermont-Ganneau, visited the site in 1874 and wrote: "The place is absolutely uninhabited, except during the rainy season, when the herdsmen take shelter there for the night."[18]

Previous attempts of identification

Early drawings depicting the so-called "Adullam cave" have tentatively been identified with the cavern of Umm el Tuweimin, and the cave at Khureitun (named after Chariton the ascetic),[19] because of their immense size. Modern-day archaeologists have rejected these early hypotheses.[20]

Nature reserve and park

The Adullam Grove Nature Reserve is a nature reserve managed by the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority. It was established in 1994.[21]

The Adullam Caves park is a JNF park of 50,000 dunams (12,355 acres (50.00 km2)) of mostly pine forests, which were planted by Jewish immigrants who settled in the Lachish region in the early years of the state. The park was prepared for public use by the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Jewish National Fund.[22]

Today the park sits in an area that is threatened by shale oil extraction through the CCR ground-heating process, with the Green Zionist Alliance and the grassroots group Save Adullam, among others, working to stop shale oil extraction in the region.[23][24][25]

Landmarks

- Archaeological sites;

- Hurvat Adullam - thought to be the site of biblical Adullam, with nearby caves.

- Hurvat Itri - remains of a Jewish village from the 1st-2nd centuries CE, containing Mikvehs, a synagogue, a columbarium, and burial caves.

- Hurvat Borgyn - remains of a 2nd-century CE settlement, including fortifications, wells, burial caves, a wine press, and other agriculture oriented finds.

- Tel Sokho

- Two marked trails for bicycle riders:

- "Sokho" track – a 13 km track heading towards Tel Sokho and then heads back.

- Track "Borgyn" – a 22 km track which passes through the ancient ruins of Itri and Borgyn, and then heads back.

Gallery

Old stone structure (Wely) at Adullam

Old stone structure (Wely) at Adullam- Photo of underground cavern and cistern at ancient ruin, Sheikh Madhkour

- Cave entrance in Adullam

Heap of boulders at lower site, ʻEid el-Mieh

Heap of boulders at lower site, ʻEid el-Mieh

See also

References

- ↑ Conder & Kitchener, The Survey of Western Palestine, vol. III, London 1883, p. 311; On Palestine Exploration Fund Map: Hebron (Sheet XXI), the ruin of Khurbet 'Aid el Ma (sic) appears directly to the north of Khurbet esh-Sheikh Madhkur, in the valley below. The ancient ruin is distinguished by its many razed structures lying in a field the size of a football field, interspersed with terebinths, directly alongside a small paved road that runs parallel to the main Roglit - Aderet road: see Survey of Western Palestine, 1878 Map, Map 21: IAA, Wikimedia commons, as surveyed and drawn under the direction of Lieut. C.R. Conder and H.H. Kitchener, May 1878. Victor Guerin believed that there was once an Upper Adullam and a Lower Adullam.

- ↑ Conder & Kitchener, Survey of Western Palestine, vol. III (Judæa), London 1883, pp. 361–367.

- ↑ Charles S. Shaw (1 November 1993). The Speeches of Micah: A Rhetorical-Historical Analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-567-21443-0.

- ↑ Claude R. Conder, in Tent Work in Palestine (pub. Richard Bentley and Son: London 1878, p. 276), wrote: "The term Shephelah is used in the Talmud to mean the low hills of soft limestone, which, as already explained, form a distinct district between the plain and the watershed mountains. The name Sifla, or Shephelah, still exists in four or five places within the region round Beit Jibrîn, and we can therefore have no doubt as to the position of that district, in which Adullam is to be sought. M. Clermont Ganneau was the fortunate explorer who first recovered the name, and I was delighted to find that Corporal Brophy had also collected it from half a dozen different people, without knowing that there was any special importance attaching to it. The title being thus recovered, without any leading question having been asked, I set out to examine the site, the position of which agrees almost exactly with the distance given by Jerome, between Eleutheropolis and Adullam—ten Roman miles."

- ↑ Joshua 12:15 and Joshua 15:35

- ↑ 1 Samuel 17:2

- ↑ Genesis 38:1

- ↑ 2 Chronicles 11:7

- ↑ Micah 1:15

- ↑ 1 Samuel 22:2

- ↑ 2 Maccabees, chapter 12

- ↑ Eusebius, Onomasticon - The Place Names of Divine Scripture, (ed.) R. Steven Notley & Ze'ev Safrai, Brill: Leiden 2005, pp. 27 (§77), 82 (§414) ISBN 0-391-04217-3. As for the word "east," this is not to be understood directly east in relation to Beit Gubrin (Eleutheropolis), as proven by other descriptions of biblical place names in Eusebius' writings, but can also mean "northeast", as in this case, or "southeast".

- ↑ Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth & Kamal Abdulfattah, Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century, Erlangen 1977, p. 122 ISBN 3-920405-41-2

- ↑ Yoel Elitzur, Ancient Place Names in the Holy Land - Preservation and History, Jerusalem / Winona Lake, Indiana 2004, p. 137 ISBN 1-57506-071-X; (The number of fiscal unit in the daftar, corresponding to the map, is "P-17").

- ↑ Toledano, Ehud (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 75.

- ↑ Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. pp. 338–339.

- ↑ Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. , p. 318.

- ↑ Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873–1874 (vol. 2), London 1896, p. 459

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement of 1875, p. 173.

- ↑ C.R. Conder, Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement of 1875, p. 145.

- ↑ "List of National Parks and Nature Reserves" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-07. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ פארק עדולם [Adullam Park] (in Hebrew). JNF website. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Krantz, David (1 May 2011). "Israel: The New Saudi Arabia?". Jewcology.

- ↑ Cheslow, Daniella (18 Dec 2011). "Shale oil project raises hackles in Israel". AFP.

- ↑ Laylin, Tafline (5 March 2013). "Saudi Turns to Solar, Israel Stuck on Shale". Green Prophet.

External links

- C. Clermont-Ganneau, The Site of the City of Adullam, Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 7.3 (July 1875), pp. 168–177

- Khirbat esh-Sheikh Madkur (west) - Israel Antiquities Authority

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adullam. |