Massacre of Glencoe

| Massacre of Glencoe Mort Ghlinne Comhann (Scottish Gaelic) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1689 | |||||||

Glencoe | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Argyll's Regiment of Foot Hill's Regiment of Foot | MacDonald of Glencoe and associates | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Major Robert Duncanson Campbell of Glenlyon Lt-Colonel Hamilton | Alasdair MacIain | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 920 estimated | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | Estimated up to 38 dead, unknown number subsequently | ||||||

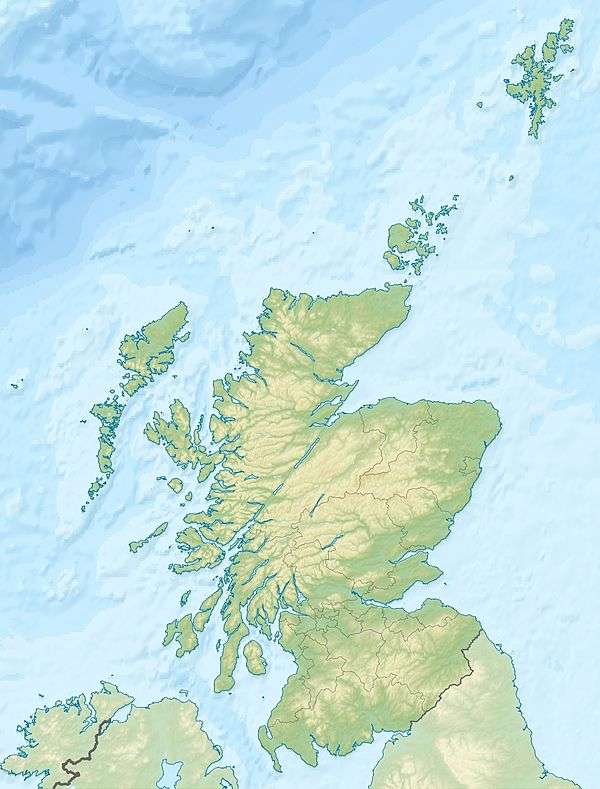

Location within Scotland | |||||||

The Massacre of Glencoe (Scottish Gaelic: Mort Ghlinne Comhann) took place in Glen Coe in the Highlands of Scotland on 13 February 1692, following the Jacobite uprising of 1689-92. An estimated thirty-eight [lower-alpha 1] members and associates of Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by government forces billeted with them, with others later alleged to have died of exposure, on the grounds they had not been prompt in pledging allegiance to the new monarchs, William III of England and II of Scotland and Mary II.[lower-alpha 2]

Background

In March 1689, James II of England and VII of Scotland[lower-alpha 3] landed in Ireland in an attempt to regain his throne and John Graham, Viscount Dundee recruited a small force of Highlanders for a similar campaign in Scotland. Despite victory at the Battle of Killiecrankie on 27 July, Dundee was killed and organised Jacobite military resistance ended with defeats at the Battle of Dunkeld in August 1689 and Cromdale in May 1690.

The continuing need to police the Highlands used resources William needed for the Nine Years' War. A peaceful Scotland was important since links between Irish and Scottish branches of the MacDonalds, as well as Scottish and Ulster Presbyterians, meant unrest in one country often spilled into the other.[3]

The Glencoe MacDonalds were one of three Lochaber clans with a reputation for lawlessness, the others being the MacGregors and the Keppoch MacDonalds. Levies from these clans served in the Independent Companies used to suppress the Conventicles in 1678–80, and took part in the devastating Atholl raid that followed Argyll's rising in 1685.[4] They also combined against their Maclean landlords in the August 1688 battle of Maol Ruadh, putting them in the unusual position of being considered outlaws by both the previous Jacobite administration and the new Williamite one.[5]

Oath of allegiance to William

After Killiecrankie, the Scottish government held a series of meetings with the Jacobite chiefs, offering terms that varied based on events in Ireland and Scotland. In March 1690, the Secretary of State, Lord Stair, offered a total of £12,000 for swearing allegiance to William. They agreed to do so in the June 1691 Declaration of Achallader, the Earl of Breadalbane signing for the government; in July, the Battle of Aughrim ended the War in Ireland and immediate prospects of a Restoration.

On 26 August, a Royal Proclamation offered a pardon to anyone taking the Oath prior to 1 January 1692, with severe reprisals for those who did not.[6] Two days later, secret articles appeared, supposedly added to the Declaration and signed by all the attendees, including Breadalbane, which cancelled it in the event of a Jacobite invasion.[7] Breadalbane claimed these were manufactured by Glengarry, the MacDonald chief; but Stair's letters reflect his belief that forged or not, none of the signatories intended to keep their word.[8] Enforcement became a key concern.

In early October, the chiefs asked James for permission to take the Oath unless he could mount an invasion before the deadline, a condition they knew to be impossible.[9] His approval was sent on 12 December and was received by Glengarry on the 23rd, but was not shared until the 28th. One suggestion is these delays were caused by intrigue between Glengarry's faction of Catholic Non-Compounders, who opposed James making any concessions to regain his throne, and Protestant Compounders, for whom concessions were essential; until 1692, Non-Compounders dominated the Jacobite agenda.[10]

As a result, MacIain of Glencoe only left for Fort William on 30 December to take the Oath from the governor, Lieutenant Colonel John Hill. Since he was not authorised to accept it, Hill sent MacIain to Inverary with a letter for the local magistrate, Sir Colin Campbell confirming his arrival before the deadline. Sir Colin administered the Oath on 6 January, after which MacIain returned home.[11] Glengarry did not swear until 4 February, with others doing so by proxy, but only MacIain was excluded from the indemnity issued by the Scottish Privy Council.[12]

Stair's letter of 2 December to Breadalbane shows the intention of making an example was taken well before the deadline for the Oath but as a much bigger operation; ...the clan Donell must be rooted out and Lochiel. Leave the McLeans to Argyll...[13] In January, he wrote three letters in quick succession to Sir Thomas Livingstone, military commander in Scotland; on 7th, the intention was to ....destroy entirely the country of Lochaber, Locheal's lands, Kippochs, Glengarrie and Glenco...; on 9th ...their chieftains all being papists, it is well the vengeance falls there; for my part, I regret the MacDonalds had not divided and...Kippoch and Glenco are safe.[14] The last on 11 January states; ...my lord Argile tells me Glenco hath not taken the oaths at which I rejoice....[15]

Parliament passed a Decree of Forfeiture in 1690, depriving Glengarry of his lands, but he continued to hold Invergarry Castle, whose garrison included the senior Jacobite officers Alexander Cannon and Thomas Buchan.[16] MacIain's son John MacDonald told the 1695 Commission the soldiers came to Glencoe from the north '...Glengarry's house being reduced.'[17] This suggests the Episcopalian Glencoe MacDonalds only replaced the Catholic Glengarry as the target on 11 January, and explains the large number of troops (over 900) available for a minor operation.

Motives varied. After two years of negotiations, Stair was under pressure to ensure the deal stuck, while Argyll was competing for political influence with his kinsman Breadalbane, who also found it expedient to concur with the plan.[18] One possible motive was a quarrel with MacIain over compensation for damage to his property of Achallader; on 15 February, his steward offered to help MacIain's sons in return for swearing he was not involved.[19] Glengarry was pardoned and his lands returned, while maintaining his reputation at the Jacobite court by being the last to swear and ensuring Cannon and Buchan received safe conduct to France in March 1692.[20] In summary, the Glencoe MacDonalds were a small clan with few friends and powerful enemies.

Massacre

In late January 1692, two companies or approximately 120 men from the Earl of Argyll's Regiment of Foot arrived in Glencoe from Invergarry. Their commander was Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, a local landowner whose niece was married to one of MacIain's sons;[lower-alpha 4] he carried orders for 'free quarter', an established alternative to paying taxes in what was a largely non-cash society.[21] The Glencoe MacDonalds themselves were similarly billeted on the Campbells when serving with the Highland levies used to police Argyll in 1678.[22]

Highland regiments were formed by first appointing Captains, each responsible for recruiting sixty men from his own estates. Muster rolls for the regiment from October 1691 show the vast majority came from Argyll, including Cowal and Kintyre, areas settled by Lowlander migrants and badly hit by the Atholl raids of 1685 and 1686.[23] There is no evidence the Massacre was related to a clan feud, but the men involved were not outsiders.[lower-alpha 5]

In his letters of 30 January to Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton and Colonel Hill, Stair expresses concern the MacDonalds would escape if warned, and emphasises the need for secrecy. This correlates with evidence from James Campbell, one of Glenlyon's company, stating they had no knowledge of the plan until the morning of 13 February.[24] On 12 February, Hill issued orders instructing Hamilton to take 400 men and block the northern exits from Glencoe at Kinlochleven. Another 400 men from Argyll's Regiment under Major Duncanson would join Glenlyon's detachment in the south and sweep northwards up the glen, killing anyone they found, removing property and burning houses.[25]

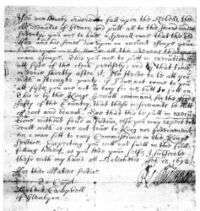

On the evening of 12 February, Glenlyon received written orders from Duncanson carried by another Argyll officer, Captan Thomas Drummond; their tone shows doubts as to his ability or willingness to carry them out. See that this be putt in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be dealt with as one not true to King nor Government, nor a man fitt to carry Commissione in the Kings service. As Captain of the Argylls' Grenadier company, Drummond was senior to Glenlyon; his presence appears to have been to ensure the orders were enforced, since witnesses gave evidence he shot two people who asked Glenlyon for mercy.[26]

The first to die was Duncan Rankin, shot down as he tried to escape by crossing the River Coe near the chief's house.[27] MacIain was killed, while nine others were shot after first being tied up but the 1695 Commission heard different figures for the total killed. The MacDonalds claimed 'the number they knew to be slaine were about 25,' but there were no witnesses from Glenlyon's company, the figure of 38 being based on hearsay evidence from Hamilton's men.[28] Another 40-100 are alleged to have died of exposure but the origin of these is unclear; recent estimates put total deaths resulting from the Massacre as 'around 30.'[29]

Casualties would have been higher, but, whether by accident or design, Hamilton and Duncanson arrived after the killings had finished. Duncanson was two hours late, only joining Glenlyon at the southern end at 7:00 am, after which they advanced up the glen burning houses and removing livestock. Hamilton was not in position at Kinlochleven until 11:00; his detachment included two lieutenants, Francis Farquhar and Gilbert Kennedy who often appear in anecdotes claiming they 'broke their swords rather than carry out their orders.' This differs from their testimony to the Commission and is unlikely, since they arrived hours after the killings, which were carried out at the opposite end of the glen.[30]

In May 1692, fears of a French invasion resulted in the Argylls being first posted first to Brentford in England, then to Flanders, where they remained until the Nine Years' War ended in 1697 and the regiment was disbanded. No further action was taken against the officers involved; Glenlyon died in Bruges in August 1696; Duncanson became a Colonel and was killed in May 1705 in Spain; while Drummond would feature in another famous Scottish disaster, the Darien Scheme.

Inquiry

The killings first came to public attention when a copy of Glenlyon's orders allegedly 'left' in an Edinburgh coffee house was smuggled to France and published in the Paris Gazette of 12 April 1692.[31] While it led to criticism of the Scottish government, there was little sympathy for the MacDonalds.[32] In a letter to Lord Hamilton, Sir Thomas Livingstone, later Viscount Teviot commented; 'it's not that anyone thinks the thieving tribe did not deserve to be destroyed but that it should have been done by those quartered amongst them makes a great noise.'[33] The primary driver was political; Stair had been a senior member of James VII's administration, and was unpopular with Jacobite loyalists and supporters of the Williamite regime.[34]

A number of observers argued events at Glencoe and elsewhere showed the Highlands could not be controlled purely by force; this included Colonel Hill, who despite his role in the Massacre was generally sympathetic towards Highlanders, arguing they were strongly inclined to live peaceably.[lower-alpha 7] He viewed the posturing of clan leaders like Glengarry as the problem, while ‘the midle sort of Gentrey and Commons....never got anything but hurt’ from it. The 1693 Highland Judicial Commission created four divisions within the Highlands, each with its own court, making it easier to use the law to resolve issues like cattle-theft. Unfortunately, this was significantly undermined by the clan chiefs themselves, since it diminished their control over their tenants and clansmen.[35]

In 1695, the massacre was referenced in a pamphlet written by Charles Leslie, a nonjuring Church of Ireland Episcopalian priest who moved to London in 1690 and produced pro-Jacobite articles until his death in 1721.[36] The focus of this tract was William's alleged complicity in the 1672 death of Dutch Republican leader Johan de Witt, but it included Glencoe and a number of other crimes.[37]

A Parliamentary Commission was set up to determine whether there was a case to answer under the charge of 'Slaughter under trust.' This 1587 law was intended to reduce endemic feuding by requiring opponents to use the Crown to settle disputes and applied to murder committed in 'cold-blood', i.e., once articles of surrender had been agreed or hospitality accepted.[38] It was subject to interpretation; in 1597, James MacDonald was charged under the law for assembling 200 men outside his parents' house, locking them inside and setting fire to it but this was later judged 'hot-blooded' and excluded.[39]

As both a capital offence and treason, it was an awkward weapon with which to attack Stair, as William himself signed the orders and the intent was widely known in government circles. The Commission therefore focused on whether participants exceeded their orders, not their legality; it concluded Stair and Hamilton had a case to answer but left the decision to William.[lower-alpha 8][40] While Stair was dismissed as Secretary of State, he remained an influential politician; he returned to government in 1700, and was made an earl by William III's successor, Anne.[41] An application by the surviving Glencoe MacDonalds for compensation was ignored; they rebuilt their houses and participated in both the 1715 and 1745 Jacobite risings.[42]

Aftermath

Despite what is often suggested, Glencoe was a savage crime but not particularly unusual; other examples involving MacDonalds include the 1578 Battle of the Spoiling Dyke and the 1647 Dunaverty Massacre. Breach of hospitality was less common, but the existence of the charge 'Slaughter under trust' shows not unknown. It was first used in 1588 to prosecute Lachlan Maclean, whose objections to his new stepfather, John MacDonald, resulted in the murder of 18 members of the MacDonald wedding party.[43] The Dunaverty killings would also have been in this category, for they allegedly took place after the garrison of 200 surrendered on terms.

The Jacobites used the Massacre as a symbol of post-1688 oppression; in 1745, Charles Stuart ordered Leslie's pamphlet and the 1695 Parliamentary minutes to be reprinted in the Edinburgh Caledonian Mercury.[44] The Massacre faded from public view until 1859, when it re-appeared in Macaulay's History; Macaulay exonerated William of every charge made by Leslie, including the Massacre and is the origin of the claim it was part of a Campbell-MacDonald feud.[45] The timing was important; Queen Victoria's liking for Balmoral popularised Scottish traditions, while Victorian Scotland developed values that were pro-Union and pro-Empire but uniquely Scottish.[46]

Historical divisions within Scottish society meant this was largely expressed through a shared cultural identity, while the study of Scottish history itself virtually disappeared from universities.[47] Glencoe became part of a focus on the emotional trappings of the Scottish past...bonnie Scotland of the bens and glens and misty shieling, the Jacobites, Mary, Queen of Scots, tartan mania and the raising of historical statuary.[48] The change can be seen by comparing Horatio McCulloch's 1864 work, where Glencoe is a wild landscape, empty of people or buildings, with Peter Graham's 1889 After the Massacre that focuses on the survivors.

When the study of Scottish history re-emerged in the 1950s, Leslie's perspectives continued to shape views of William's reign as particularly disastrous for Scotland, with Glencoe part of a series of incidents like the Darien scheme, the famine of the late 1690s, and ultimately Union in 1707.[49] Advances in modern Scottish historiography means this is less true, but the Scottish Republican Socialist Movement still holds an annual event portraying Glencoe as a colonialist action of the London government. The SRSM is a tiny group, but sectarian divides within modern Scottish politics mean that view is not uncommon.[lower-alpha 9]

The Massacre is the centre of an annual ceremony initiated in 1930 by Mary Rankin from Taigh a’ phuirt, Glencoe, and continued by her family.[50] On 13 February each year the Clan Donald Society holds a wreath-laying ceremony attended by members from around the world at the Upper Carnoch memorial; this is a tapering Celtic cross designed in 1883 by MacDonald of Aberdeen and located at the eastern end of Glencoe village, formerly known as Carnoch.[51]

In 1998, the so-called Henderson Stone was set up at Glencoe; this purports to mark the location used by associates of the MacDonalds to warn of impending raids.[52] These were allegedly members of Clan Henderson, who acted as pipers for the MacIain.[53]

In popular culture

Glencoe was a popular topic with 19th century poets, the best-known work being Sir Walter Scott's "Massacre of Glencoe".[54] It was used as a subject by Thomas Campbell and George Gilfillan, whose main claim to modern literary fame is his sponsorship of William McGonagall, allegedly the worst poet in British history. Other poetic references include Letitia Elizabeth Landon's "Glencoe" (1823), T. S. Eliot's "Rannoch, by Glencoe" and "Two Poems from Glencoe" by Douglas Stewart.[55]

Examples of its appearance in literature include "The Masks of Purpose" by Eric Linklater, and the novels Fire Bringer by David Clement-Davies, Corrag by Susan Fletcher and Lady of the Glen by Jennifer Roberson. William Croft Dickinson references Glencoe in his 1963 short story "The Return of the Native".

The Mad Men episode "Time & Life" references the massacre when headmaster Bruce MacDonald in the year 1970 still holds a grudge against Pete Campbell.[56]

The Glencoe massacre and murder of the Douglasses at the Black Dinner of 1440 allegedly inspired the event known as 'The Red Wedding' in George R. R. Martin's novel A Storm of Swords and the HBO series Game of Thrones.[57]

Archaeology

In 2018, a team of archeologists organised by the National Trust for Scotland began surveying several areas related to the massacre, with plans to produce detailed studies of their findings.[58][59]

See also

- List of massacres in the United Kingdom

- Betrayal of Clannabuidhe, a similar incident in Ireland

- Achallader Castle, where the chiefs gathered together to meet John Campbell

Notes

- ↑ This is the generally accepted figure but the actual number remains unclear; the MacDonalds told the 1695 Commission 'the number...slaine were about 25.' Derek Alexander, Head of Archaeology at the National Trust of Scotland, gives '30 confirmed dead, unknown number subsequently.'[2]

- ↑ Since England and Scotland were then separate kingdoms, William was technically William III of England and William II of Scotland; to simplify, he is referred to as William.

- ↑ As above, referred to as James.

- ↑ As per John Prebble's account 'Glencoe; the Story of the Massacre,' this was John MacDonald, who served in the Jacobite force under Thomas Buchan scattered at Cromdale in May 1690.

- ↑ Clan Campbell includes those named Campbell but also a large number of so-called 'septs, a complete list of which can be found on the Clan Campbell website. This means the number of individuals called 'Campbell' on the Argyll muster rolls is not an accurate reflection of clan affiliation.

- ↑ You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebells, the McDonalds of Glenco, and put all to the sword under seventy. you are to have a speciall care that the old Fox and his sones doe upon no account escape your hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man escape. This you are to putt in execution att fyve of the clock precisely; and by that time, or very shortly after it, I’ll strive to be att you with a stronger party: if I doe not come to you att fyve, you are not to tarry for me, but to fall on. This is by the Kings speciall command, for the good & safety of the Country, that these miscreants be cutt off root and branch. See that this be putt in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be dealt with as one not true to King nor Government, nor a man fitt to carry Commissione in the Kings service. Expecting you will not faill in the full-filling hereof, as you love your selfe, I subscribe these with my hand att Balicholis Feb: 12, 1692.

- ↑ In September 1693, he claimed even the MacDonald septs in Lochaber were fully law-abiding and that ‘a single person may travell safley where he will witout harme.’

- ↑ The Commission was not a legal court and did not determine guilt or innocence but only whether charges might be brought.

- ↑ 'The Massacre, carried out by one group of Scottish Highlanders on another upon orders drafted by a Scottish Secretary and counter-signed by a Dutch king is something for which naturally no true Scot will ever forgive the English.' Paul Hopkins, from Glencoe and the End of the Highland War.

References

- ↑ "Site Record for Glencoe, National Trust For Scotland Glencoe Visitor Centre". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. . Location of NTS visitor centre.

- ↑ Campsie, Alison (12 February 2018). "The Scotsman". Archaeologists trace lost settlements of Glencoe destroyed after 1692 massacre. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ The History of Scotland Volume 3 Andrew Lang P284-286

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 128. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 137. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Papers Illustrative of the Political Condition of the Highlands of Scotland, 1689–1706; John Gordon 2016

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 139. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Correspondence of Lord Stair; Papers Illustrative of the Political Condition of the Highlands of Scotland, 1689–1706; John Gordon 2016

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Buchan, John (1991). Massacre of Glencoe (First Published 1933 ed.). Lang Syne Publishers Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 1852171642.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 140. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Goring, Rosemary (2014). Scotland: The Autobiography: 2,000 Years of Scottish History by Those Who Saw it Happen. Penguin. pp. 94–100. ISBN 0241969166.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 538. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Goring, Rosemary (2014). Scotland: The Autobiography: 2,000 Years of Scottish History by Those Who Saw it Happen. Penguin. pp. 94–100. ISBN 0241969166.

- ↑ Love, Dane (2007). Jacobite Stories. End of Chapter 3: Neil Wilson Publishing. ISBN 1903238862. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Cobbett, William (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors (2011 ed.). Nabu Press. p. 904. ISBN 1175882445.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 141. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Cobbett, William (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors (2011 ed.). Nabu Press. p. 904. ISBN 1175882445.

- ↑ MacConechy, James (1843). Papers Illustrative of the Political Condition of the Highlands of Scotland (2012 ed.). Nabu Press. p. 77. ISBN 1145174388. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ Kennedy, Allan (2014). Governing Gaeldom: The Scottish Highlands and the Restoration State 1660–1688. Brill. p. 141. ISBN 9004248374.

- ↑ Lenman Bruce, Mackie JL (1991). A History of Scotland. Penguin. pp. 238–239. ISBN 0140136495.

- ↑ Argyll Transcripts, ICA (1891). "An Account of the depredations committed on the Clan Campbell and their followers during the years 1685 and 1686". Historical Manuscripts Commission. 11: 12–24.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 537. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 538. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 536. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ John Prebble, Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre, Secker & Warburg, Ltd, 1966; Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-002897-8, 1972.

- ↑ Cobbett William, Howell Thomas (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors (2011 ed.). Nabu Press. pp. 902–903. ISBN 1175882445. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ Campsie, Alison (12 February 2018). "The Scotsman". Archaeologists trace lost settlements of Glencoe destroyed after 1692 massacre. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Howell, Thomas Bayly (2017). A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 903. ISBN 1333019327. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 143. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Prebble, John (1973). Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre. Penguin. p. 197. ISBN 0140028978.

- ↑ Prebble, John (1973). Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre. Penguin. p. 198. ISBN 0140028978.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 141. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Kennedy, Allan (April 2017). "Managing the Early Modern Periphery: Highland Policy and the Highland Judicial Commission, c. 1692–c. 1705". The Scottish Historical Review. 96 (1): 32–60. doi:10.3366/shr.2017.0313.

- ↑ Charles Leslie & Theological Politics in Post Revolutionary England; William Frank, B.A., Thesis for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University February 1983

- ↑ Gallienus Redivivus, or Murther will out, &c. Being a true Account of the De Witting of Glencoe, Gaffney,’ Edinburgh, 1695

- ↑ Harris, Tim (2015). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567–1642. OUP Oxford. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0198743114.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 128. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Scott Walter, Somers John (2014). A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III. Nabu Press. p. 545. ISBN 1293842222.

- ↑ Hopkins, Paul (1998). Glencoe and the end of the Highland Wars. John Donald Publishers Ltd. pp. 395–436. ISBN 0859764907.

- ↑ Prebble, John (1973). Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre. Penguin. p. 214. ISBN 0140028978.

- ↑ Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Berghahn Books. p. 129. ISBN 1571819355.

- ↑ Hopkins, Paul (1998). Glencoe and the end of the Highland Wars. John Donald Publishers Ltd. p. 1. ISBN 0859764907.

- ↑ Macaulay, History of England, iv. 213 n., 8 Volume

- ↑ Victorian Values in Scotland and England; RJ Morris, Proceedings of the British Academy 78 1992 P37-39

- ↑ Kidd, Colin (April 1997). "The Strange Death of Scottish History Revisited; Constructions of the Past in Scotland c1790-1914". Scottish Historical Review. lxxvi (100).

- ↑ Ash, Marinell (1980). The Strange Death of Scottish History. Ramsay Head Press. p. 10. ISBN 0902859579.

- ↑ Kennedy, Allan (April 2017). "Managing the Early-Modern Periphery: Highland Policy and the Highland Judicial Commission, c. 1692–c. 1705". Scottish Historical Review. XCVI, 1 (242): 32–33. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ The Oban Times, 22 February 1958.

- ↑ "Site Record for Glencoe, Massacre Of Glencoe Memorial; Macdonald's Monument; Glencoe Massacre". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 4 November 2013. . Memorial is at grid reference NN1050958793.

- ↑ Pagan, Sue (17 September 1998). "Henderson Stone dedicated at Glencoe". The Oban Times. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "Clan Henderson Society". Clan Henderson.org. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Sir Walter Scott. "On the Massacre of Glencoe". Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Stewart Douglas. Two Poems from Glencoe Archived 15 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine., at Australian Poetry Library. Accessed 5 October 2015

- ↑ Thomas, Leah. "Is Pete Campbell's Ancient Feud Real On 'Mad Men'? The Show Took An Interesting Historical Turn". Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "'Game Of Thrones' Red Wedding Based On Real Historical Events: The Black Dinner And Glencoe Massacre". Huffington Post. 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ Treviño, Julissa (26 March 2018). "Archaeologists Trace 'Lost Settlements' of 1692 Glencoe Massacre". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Metcalfe, Tom (19 March 2018). "17th-Century Houseguests Slaughtered Hosts, and Archaeologists Are Investigating". livescience.com. Purch. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

Sources

- Argyll Transcripts; An Account of the depredations committed on the Clan Campbell and their followers during the years 1685 and 1686; (Historical Manuscripts Commission, 1981);

- Ash, Marinell; The Strange Death of Scottish History; (Ramsay Head Press, 1980);

- Buchan, John; Massacre of Glencoe; (Lang Syne Publishers Ltd, 1933 (ed));

- Browne, James; The history of Scotland, its Highlands, regiments and clans; (Amazon Kindle, first published 1838);

- Cobbett, William; Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors, 1814; (Nabu Press, 2011);

- Frank, William; Charles Leslie & Theological Politics in Post Revolutionary England;(PHD Thesis McMaster University, 1983);

- Goring, Rosemary; Scotland, the Autobiography – 2,000 Years of Scottish History by Those Who Saw it Happen, 2014;

- Harris, Tim; Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567–1642;, (OUP, 2015);

- Hopkins, Paul; Glencoe and the end of the Highland Wars; (John Donald Publishing, 1998);

- Howell, Thomas Bayly; A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason, 2017 ed;

- Hunter, James; Glencoe and the Indians; 2011;

- Kennedy, Allan; Governing Gaeldom: The Scottish Highlands and the Restoration State, 1660–1688 (2014;

- Kidd, Colin; The Strange Death of Scottish History Revisited; Constructions of the Past in Scotland c1790-1914; (Scottish Historical Review, 1997);

- Love, Dane; Jacobite Stories; (Neil Wilson Publishing, 2007);

- Lenman, Bruce; The Jacobite Risings in Britain 1689–1746; (1980;

- Lenman, Bruce & Mackie JL; A History of Scotland; 1991;

- Leslie, Charles; Gallienus Redivivus, or Murther will out, &c. Being a true Account of the De Witting of Glencoe, (Gaffney, 1695);

- Levine, Mark (editor); The Massacre in History (War and Genocide); (Berghahn Books, 1990);

- MacConechy, James; Correspondence of Lord Stair; Papers Illustrative of the Political Condition of the Highlands of Scotland, 1689–1706; (John Gordon, 2016 ed);

- Morris, RJ; Victorian Values in Scotland and England; (Proceedings of the British Academy, 1992;)

- Prebble, John; Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre, (Penguin, 1973 ed);

- Scott Walter, Somers John; A Collection Of Scarce And Valuable Tracts, On The Most Interesting And Entertaining Subjects: Reign Of King James II. Reign Of King William III; (Nabu Press, 2014);

- Szechi, Daniel; The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788; (Manchester University Press, 1994);

External links

- Glencoe Massacre on In Our Time at the BBC

- Parliamentary Register, with full details of the Commission of Inquiry's Address to William III, 10 July 1695;

- History – Massacre of Glencoe 1692—BBC: brief account of the massacre

- Macaulay's History of England, chapter XVIII Includes a well written and moderately detailed account of the massacre in its political context, with footnotes to original source documents. However, it should be read with caution as Macaulay had a very specific perspective.

- Glen Coe Massacre Detailed account of the events leading up to the massacre and the massacre itself.

- Glencoe Very detailed and balanced account of the plot and massacre.

- Medieval Scottish Calendar and Holidays Discussion of the need for care in discussing historical dates as they apply in Scotland, due to change of New Year in 1600 and general adoption of Gregorian Calendar.

- The Vale of Glencoe Radio episode from the series Quiet, Please. Poor sound quality, but the radio script may be found below.

- The Vale of Glencoe Radio Script OTR Plot Spot—plot summaries, scripts and reviews of Old Time Radio shows, including "The Vale of Glencoe", above.

.svg.png)