1872 Lone Pine earthquake

Lone Pine fault scarp | |

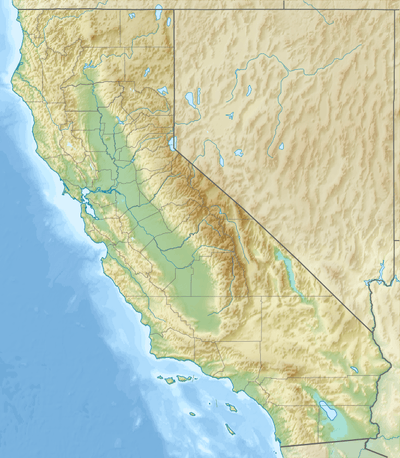

San Diego Sacramento Lone Pine | |

| Local date | March 26, 1872 |

|---|---|

| Local time | 02:30 [1] |

| Magnitude | 7.4–7.9 Mw [2] |

| Epicenter | 36°42′N 118°06′W / 36.7°N 118.1°WCoordinates: 36°42′N 118°06′W / 36.7°N 118.1°W [1] |

| Type | Oblique-slip [2] |

| Areas affected |

Eastern California United States |

| Total damage | $250,000 / limited [3] |

| Max. intensity | X (Extreme) [1] |

| Casualties | |

| Official name | Grave of 1872 Earthquake Victims[5] |

| Reference no. | 507 |

The 1872 Lone Pine earthquake struck on March 26 at 02:30 local time with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.4 to 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli Intensity of X (Extreme). Its epicenter was near Lone Pine, California, in Owens Valley. It was one of the largest earthquakes to hit California in recorded history and was similar in size to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Twenty-seven people were killed and fifty-six were injured.

Tectonic setting

The earthquake resulted from sudden vertical movement of 15–20 feet (4.5–6m) and right-lateral movement of 35–40 feet (10.6–12m) on the Lone Pine Fault and part of the Owens Valley Fault. These faults are part of a twin system of normal faults that run along the base of two parallel mountain ranges; the Sierra Nevada on the west and Inyo Mountains on the east of the Owens Valley. It created fault scarps from north of Big Pine, 55 mi (89 km) north of Lone Pine, to Haiwee Reservoir (30 mi (48 km)) south of Lone Pine.

Earthquake

The earthquake occurred on a Tuesday morning and leveled almost all the buildings in Lone Pine and nearby settlements.[4] Of the estimated 250–300 inhabitants of Lone Pine, 27 are known to have perished and 52 of the 59 houses were destroyed. One report states that the main buildings were thrown down in almost every town in Inyo County. About 130 kilometers (81 mi) south of Lone Pine, at Indian Wells, Kern County, California, adobe houses sustained cracks. Property loss has been estimated at $250,000 (1872 dollars). As in many earthquakes, adobe, stone and masonry structures fared worse than wooden ones which prompted the closing of nearby Camp Independence which was an adobe structure destroyed in the quake.

The quake was felt strongly as far away as Sacramento, where citizens were startled out of bed and into the streets. Giant rockslides in what is now Yosemite National Park woke naturalist John Muir, then living in Yosemite Valley, who reportedly ran out of his cabin shouting, "A noble earthquake!" and promptly made a moonlit survey of the fresh talus piles. This earthquake stopped clocks and awakened people in San Diego, California, to the south, Red Bluff, California, to the north, and Elko, Nevada, to the east. The shock was felt over most of California and much of Nevada. Thousands of aftershocks occurred, some severe.

Aftermath

Researchers later estimated that similar earthquakes occur on the Lone Pine fault every 3,000–4,000 years. However, the Lone Pine fault is only one of many faults on two parallel systems.

This earthquake also formed a small graben that later was filled by water, creating 86-acre (350,000 m2) Diaz Lake.[6]

The common grave of the earthquake's victims is now registered as California Historical Landmark #507.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Stover, C. W.; Coffman, J. L. (1993), Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (Revised), U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1527, United States Government Printing Office, pp. 73, 105

- 1 2 Hough, S. E.; Hutton, K. (2008), "Revisiting the 1872 Owens Valley, California, Earthquake", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 98 (2): 931, 932, Bibcode:2008BuSSA..98..931H, doi:10.1785/0120070186

- 1 2 National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS), Significant Earthquake Database, National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K

- 1 2 "State's Biggest Quake Struck 100 Years Ago". Los Angeles Times. Mar 26, 1972.

- 1 2 "Grave of 1872 Earthquake Victims". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ Hall, Jr., C. A. (2007). Introduction to the geology of southern California and its native plants. University of California Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-520-24932-5.

- Bibliography

- Amos, C. B.; Lutz, A. T.; Jayko, A. S.; Mahan, S. A.; Fisher, G. Burch; Unruh, J. R. (2013), "Refining the Southern Extent of the 1872 Owens Valley Earthquake Rupture through Paleoseismic Investigations in the Haiwee Area, Southeastern California", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 103 (2A): 1022–1037, Bibcode:2013BuSSA.103.1022A, doi:10.1785/0120120024

- Sharp, R. P.; Glazner, A. F. (1997). Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley (First ed.). Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-362-0.