Wars of the Roses

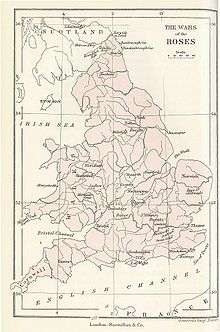

The Wars of the Roses were a series of English civil wars for control of the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival cadet branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the House of Lancaster, represented by a red rose, and the House of York, represented by a white rose. Eventually, the wars eliminated the male lines of both families. The conflict lasted through many sporadic episodes between 1455 and 1487, but there was related fighting before and after this period between the parties. The power struggle ignited around social and financial troubles following the Hundred Years' War, unfolding the structural problems of bastard feudalism, combined with the mental infirmity and weak rule of King Henry VI which revived interest in the House of York's claim to the throne by Richard of York. Historians disagree on which of these factors was the main reason for the wars.[5]

| Wars of the Roses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Framed print after 1908 painting by Henry Payne of the scene in the Temple Garden from Shakespeare's play Henry VI, Part 1, where supporters of the rival factions pick either red or white roses | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

With the Duke of York's death in 1460, the claim transferred to his heir, Edward. After a series of Yorkist victories from January–February 1461, Edward claimed the throne on 4 March 1461, and the last serious Lancastrian resistance ended at the decisive Battle of Towton. Edward was thus unopposed as the first Yorkist king of England, as Edward IV. Resistance smouldered in the North of England until 1464, but the early part of his reign remained relatively peaceful.

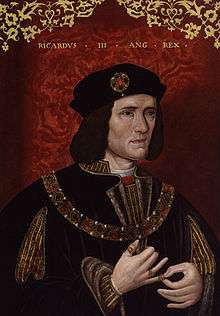

A new phase of the wars broke out in 1469 after the Earl of Warwick, the most powerful noble in the country, withdrew his support for Edward and threw it behind the Lancastrian cause. Fortunes changed many times as the Yorkist and Lancastrian forces exchanged victories throughout 1469–70 (and Edward was even captured for a time in 1469). When Edward fled to Flanders in 1470, Henry VI was re-installed as king on 3 October 1470, but his resumption of rule was short-lived, and he was deposed again following the defeat of his forces at the Battle of Tewkesbury, and on 21 May 1471, Edward entered London unopposed, resumed the throne, and probably had Henry killed that same day. With all significant Lancastrian leaders now banished or killed, Edward ruled unopposed until his sudden death in 1483. His 12-year-old son reigned for 78 days as Edward V. He was then deposed by his uncle, Edward IV's brother Richard, who became Richard III.

The accession of Richard III occurred under a cloud of controversy, and shortly after assuming the throne, the wars sparked anew with Buckingham's rebellion, as many die-hard Yorkists abandoned Richard to join Lancastrians. While the rebellions lacked much central coordination, in the chaos the exiled Henry Tudor, son of Henry VI's half-brother Edmund Earl of Richmond, and the leader of the Lancastrian cause returned to the country from exile in Brittany at the head of an army of combined Breton and English forces. Richard avoided direct conflict with Henry until the Battle of Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485. After Richard III was killed and his forces defeated at Bosworth Field, Henry assumed the throne as Henry VII and married Elizabeth of York, the eldest daughter and heir of Edward IV, thereby uniting the two claims. The House of Tudor ruled the Kingdom of England until 1603, with the death of Elizabeth I, granddaughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York.

Shortly after Henry took the throne, the Earl of Lincoln, a Yorkist sympathizer, put forward Lambert Simnel as an impostor Edward Plantagenet, a potential claimant to the throne. Lincoln's forces were defeated, and he was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field on 16 June 1487.

Name and symbols

The name "Wars of the Roses" refers to the heraldic badges associated with two rival branches of the same royal house, the White Rose of York and the Red Rose of Lancaster. Wars of the Roses came into common use in the 19th century after the publication in 1829 of Anne of Geierstein by Sir Walter Scott.[6][7] Scott based the name on a scene in William Shakespeare's play Henry VI, Part 1 (Act 2, Scene 4), set in the gardens of the Temple Church, where a number of noblemen and a lawyer pick red or white roses to show their loyalty to the Lancastrian or Yorkist faction respectively.

The Yorkist faction used the symbol of the white rose from early in the conflict, but the Lancastrian red rose was introduced only after the victory of Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, when it was combined with the Yorkist white rose to form the Tudor rose, which symbolised the union of the two houses;[8] the origins of the Rose as a cognizance itself stem from Edward I's use of "a golden rose stalked proper." [9] Often, owing to nobles holding multiple titles, more than one badge was used: Edward IV, for example, used both his sun in splendour as Earl of March, but also his father's falcon and fetterlock as Duke of York. Badges were not always distinct; at the Battle of Barnet, Edward's 'sun' was very similar to the Earl of Oxford's Vere star, which caused fateful confusion.[10]

Most, but not all, of the participants in the wars wore livery badges associated with their immediate lords or patrons under the prevailing system of bastard feudalism; the wearing of livery was by now confined to those in "continuous employ of a lord", thus excluding, for example, mercenaries.[11] Another example: Henry Tudor's forces at Bosworth fought under the banner of a red dragon[12] while the Yorkist army used Richard III's personal device of a white boar.[13]

Although the names of the rival houses derive from the cities of York and Lancaster, the corresponding duchy and dukedom had little to do with these cities. The lands and offices attached to the Duchy of Lancaster were mainly in Gloucestershire, North Wales, Cheshire, and (ironically) in Yorkshire, while the estates and castles of the Duke of York were spread throughout England and Wales, many in the Welsh Marches.[14]

Summary of events

Tensions within England during the 1450s centred on the mental state of Henry VI and on his inability to produce an heir with his wife, Margaret of Anjou. In the absence of a direct heir, there were two rival branches with claims to the throne should Henry die without issue, those being the Beaufort family, led by Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, and the House of York, headed by Richard of York. By 1453, issues had come to a head: though Margaret of Anjou was pregnant, Henry VI was descending into increasing mental instability, by August becoming completely non-responsive and unable to govern. A Great Council of nobles was called, and through shrewd political machinations, Richard had himself declared Lord Protector and chief regent during the mental incapacity of Henry. In the interlude, Margaret gave birth to a healthy son and heir, Edward of Westminster.

By 1455, Henry had regained his faculties, and open warfare came at the First Battle of St Albans. Several prominent Lancastrians died at the hands of the Yorkists. Henry was again imprisoned, and Richard of York resumed his role as Lord Protector. Although peace was temporarily restored, the Lancastrians were inspired by Margaret of Anjou to contest York's influence.

Fighting resumed more violently in 1459. York and his supporters were forced to flee the country, and Henry was once again restored to direct rule, but one of York's most prominent supporters, the Earl of Warwick, invaded England from Calais in October 1460 and captured Henry VI yet again at the Battle of Northampton. York returned to the country and for the third time became Protector of England, but was dissuaded from claiming the throne, though it was agreed that he would become heir to the throne (thus displacing Henry and Margaret's son, Edward of Westminster, from the line of succession). Margaret and the remaining Lancastrian nobles gathered their army in the north of England.

When York moved north to engage them, he and his second son Edmund were killed at the Battle of Wakefield in December 1460. The Lancastrian army advanced south and released Henry at the Second Battle of St Albans but failed to occupy London and subsequently retreated to the north. York's eldest son Edward, Earl of March, was proclaimed King Edward IV. He gathered the Yorkist armies and won a crushing victory at the Battle of Towton in March 1461.

After Lancastrian revolts in the north were suppressed in 1464, Henry was captured once again and placed in the Tower of London. Edward fell out with his chief supporter and adviser, the Earl of Warwick (known as the "Kingmaker"), after Edward's unpopular and secretly conducted marriage with the widow of a Lancastrian supporter, Elizabeth Woodville. Within a few years, it became clear that Edward was favouring his wife's family and alienating several friends closely aligned with Warwick as well.

Furious, Warwick tried first to supplant Edward with his younger brother George, Duke of Clarence, establishing the alliance by marriage to his daughter, Isabel Neville. When that plan failed, due to lack of support from Parliament, Warwick sailed to France with his family and allied with the former Lancastrian Queen, Margaret of Anjou, to restore Henry VI to the throne.

This resulted in two years of rapid changes of fortune before Edward IV once again won complete victories at Barnet (14 April 1471), where Warwick was killed, and Tewkesbury (4 May 1471), where the Lancastrian heir, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales was killed or perhaps executed after the battle. Queen Margaret was escorted to London as a prisoner, and Henry was murdered in the Tower of London several days later, ending the direct Lancastrian line of succession.

A period of comparative peace followed, ending with the unexpected death of King Edward in 1483. His surviving brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, first moved to prevent the unpopular Woodville family of Edward's widow from participating in the government during the minority of Edward's son, Edward V, and then seized the throne for himself, using the suspect legitimacy of Edward IV's marriage as pretext.

Henry Tudor, a distant relative of the Lancastrian kings who had inherited their claim, defeated Richard III at Bosworth in 1485. He was crowned Henry VII and married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV, to unite and reconcile the two houses. Yorkist revolts, directed by John de la Pole, 1st Earl of Lincoln and others, flared up in 1487 under the banner of the pretender Lambert Simnel—who claimed he was Edward, Earl of Warwick (son of George of Clarence), resulting in the last pitched battles.

Though most surviving descendants of Richard of York were imprisoned, sporadic rebellions continued until 1497, when Perkin Warbeck, who claimed he was the younger brother of Edward V, one of the two disappeared Princes in the Tower, was imprisoned and later executed.

Origins of the conflict

Disputed succession

In the early Middle Ages, the succession to the crown was open to any member (Ætheling) of the royal family. From the 9th century, the term was used in a much narrower context and came to refer exclusively to members of the house of Cerdic of Wessex, the ruling dynasty of Wessex, most particularly the sons or brothers of the reigning king. According to historian Richard Abels "King Alfred transformed the very principle of royal succession. Before Alfred, any nobleman who could claim royal descent, no matter how distant, could strive for the throne. After him, throne-worthiness would be limited to the sons and brothers of the reigning king."[15] Alfred himself succeeded to the throne in preference to the sons of his brother the previous king, who were underage at the time. In the reign of Edward the Confessor, Edgar the Ætheling received the appellation as the grandson of Edmund Ironside, but that was at a time when for the first time in 250 years there was no living ætheling according to the strict definition.

William the Conqueror's son King Henry I of England died in 1135 after William Adelin (William Ætheling), his only male heir, was killed aboard the White Ship. Following the White Ship disaster, England entered a period of prolonged instability known as The Anarchy. However, following the ascension of Henry of Anjou to the throne in 1154 as Henry II, the crown passed from father to son or brother to brother with little difficulty until 1399.[16]

The question of succession after Edward III's death in 1377 is said to be the cause of the Wars of Roses.[17] He had five surviving legitimate sons: Edward, the Black Prince (1330–1376); Lionel, Duke of Clarence (called 'Lionel of Antwerp' 1338–1368); John, Duke of Lancaster (called 'John of Gaunt'; 1340–1399); Edmund, Duke of York (called 'Edmund of Langley' 1341–1402); and Thomas, Duke of Gloucester (1355–1397). Although Edward III's succession seemed secure, there was a "sudden narrowing in the direct line of descent" near the end of his reign.[18] His eldest son Edward, the Black Prince, had died the year before. Edward III was succeeded on the throne by the Black Prince's only surviving son Richard II, who was only 10 years old.[19] Richard's claim to the throne was based on the principle that the son of an elder brother had priority in the succession over his uncles. Since Richard was a minor, had no siblings, and had three living uncles at the time of Edward III's death, there was considerable uncertainty about who was next in line for the succession after Richard.[20]

If Richard II died without legitimate offspring, his successors by primogeniture would be the descendants of Lionel of Antwerp, Edward III's second son. Clarence's only daughter, Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster, married into the Mortimer family and had a son, Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March (1374–1398), who technically had the best claim to succeed. However, a legal decree issued by Edward III in 1376 introduced some complexity into the question of who would ultimately take the throne. The letters patent he issued limited the right of succession to male heirs, which placed his third son, John of Gaunt, ahead of Clarence's descendants because the Mortimer line of descent passed through a daughter.[18]

Richard II's reign was marked by increasing dissension between the King and several of the most powerful nobles.[21] Richard's government had become highly unpopular beyond his strongholds in Cheshire and Wales. Throughout his reign, Richard had repeatedly switched his choice of the heir to keep his political enemies at bay[22] and perhaps to reduce the chances of deposition. Nevertheless, when Henry Bolingbroke (son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster) returned from exile in 1399, initially to reclaim his rights as Duke of Lancaster, he took advantage of the support of most of the nobles to depose Richard and was crowned King Henry IV, establishing the House of Lancaster on the throne.

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster descended from John of Gaunt, the third surviving son of Edward III of England. Their name derives from John of Gaunt's primary title of Duke of Lancaster, which he held by right of his spouse, Blanche of Lancaster. They had received explicit preference from Edward III in the line of succession because they formed the most senior unbroken male line of descent from him.

Henry IV's claim to the throne was through his father, John of Gaunt. At the onset of Richard II's reign, Gaunt was the official heir presumptive, but due to the intrigues of his turbulent rule, the succession was unclear by the time of his deposition. Therefore, an argument could be made that the legitimate king of England was not Henry IV, but instead was Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, the son of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March. However, there was little support at the time for his counter-claim. Certainly, many people believed it to be the case. As Henry's initial popularity waned, the Mortimer family's claim to the throne was a pretext for the major rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in Wales, and other, less successful, revolts in Cheshire and Northumberland. There were uprisings in support of the Mortimers' claim throughout Henry IV's reign, which lasted until 1413.

A peculiarity of Henry IV's seizure of the throne is demonstrated in the way he announced his claim. He was vague, and he resigned himself to mentioning that he was the rightful heir of Henry III, who had died more than a century before, perhaps subtly implying that all English kings ever since (Edward I, Edward II, Edward III and Richard II) had not been rightful monarchs. Henry IV seems to have been exploiting a legend that Henry III's second son Edmund "Crouchback", 1st Earl of Lancaster, was his eldest son but had been removed from the succession because he had a physical deformity, which gave origin to his nickname. Since Henry IV was Edmund's descendant and heir through his mother Blanche of Lancaster, he was the rightful king. There is no evidence for this legend, and Edmund's nickname did not stem from a deformity.

An important branch of the House of Lancaster was the House of Beaufort, whose members were descended from Gaunt by his mistress, Katherine Swynford. Originally illegitimate, they were made legitimate by an Act of Parliament when Gaunt and Katherine later married. However, Henry IV excluded them from the line of succession to the throne.[23]

Henry IV's son and successor, Henry V, inherited a temporarily pacified nation, and his military success against France in the Hundred Years' War bolstered his popularity, enabling him to strengthen the Lancastrian hold on the throne. Nevertheless, one notable conspiracy against Henry, the Southampton Plot, took place during his nine-year reign. This was led by Richard, Earl of Cambridge, who attempted to place Edmund Mortimer, his brother-in-law, in the throne. Cambridge was executed for treason in 1415, at the start of the campaign that led to the Battle of Agincourt.

House of York

The founder of the House of York was Edmund of Langley, the fourth son of Edward III and the younger brother of John of Gaunt. Their family name comes from Edmund's title Duke of York, which he acquired in 1385. However, the superiority of their claim is not based on the male line, but on the female line, as descendants of Edward III's second son Lionel of Antwerp. Edmund's second son, Richard, Earl of Cambridge, who was executed by Henry V, had married Anne de Mortimer, daughter of Roger Mortimer and sister of Edmund Mortimer. Anne's grandmother, Philippa of Clarence, was the daughter of Lionel of Antwerp. The Mortimers were the most powerful marcher family of the fourteenth century.[24] G.M. Trevelyan has written that "the Wars of the Roses were to a large extent a quarrel between Welsh Marcher Lords, who were also great English nobles, closely related to the English throne."[25]

Anne de Mortimer had died in 1411. When her brother Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, who had loyally supported Henry, died childless in 1425, the title and extensive estates of the Earldom of March and the Mortimer claim to the throne thus passed to Anne's descendants.

Richard of York, the son of Cambridge and Anne Mortimer, was four years old at the time of his father's execution. Although Cambridge was attainted, Henry V later allowed Richard to inherit the title and lands of Cambridge's elder brother Edward, Duke of York, who had died fighting alongside Henry at Agincourt and had no issue. Henry, who had three younger brothers and was himself in his prime and recently married to the French princess, Catherine of Valois,[24] did not doubt that the Lancastrian right to the crown was secure.

Henry's premature death in 1422, at the age of 36, led to his only son Henry VI coming to the throne as an infant and the country being ruled by a divided council of regency. Henry V's younger brothers produced no surviving legitimate issue, leaving only distant cousins (the Beauforts) as alternative Lancaster heirs. As Richard of York grew into maturity and questions were raised over Henry VI's fitness to rule, Richard's claim to the throne thus became more significant. The revenue from the York and March estates also made him the wealthiest magnate in the land.[14]

Henry VI

From early childhood, Henry VI was surrounded by quarrelsome councillors and advisors. His younger surviving paternal uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, sought to be named Lord Protector and deliberately courted the popularity of the common people for his own ends[26] but was opposed by his half-uncle Cardinal Henry Beaufort. On several occasions, Beaufort called on John, Duke of Bedford, Humphrey's older brother, to return from his post as Henry VI's regent in France, either to mediate or to defend him against Humphrey's accusations of treason.[27] Henry VI's coming of age in 1437 brought no end to the noblemen's scheming, as his weak personality made him prone to being swayed and influenced by select courtiers, especially those whom he deemed his favourites. Sometime after, Cardinal Beaufort withdrew from public affairs, partly due to old age and partly because William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, rose to become the dominant personality at court.[28] Suffolk and the Beauforts were widely held to be enriching themselves through their influence on Henry and were blamed for mismanaging the government and poorly executing the continuing Hundred Years' War with France. Under Henry VI, all the land in France won by Henry V and even the provinces of Guienne and Gascony, which had been held since the reign of Henry II three centuries previously, were lost.

Opposition to Suffolk and Beaufort was led by Humphrey of Gloucester, and Richard of York. Humphrey felt that the lifetime efforts of his brothers, of himself, and many Englishmen in the war against France were being wasted as the French territories slipped from English hands, especially since Suffolk and his supporters were trying to make large diplomatic and territorial concessions to the French in a desperate attempt for peace. In this, Gloucester enjoyed little influence, as Henry VI tended to favour Suffolk and Beaufort's faction at court due to its less hawkish and more conciliatory inclinations. The Duke of York, Bedford's successor in France, and at times also described as a skeptic of the peace policy, became entangled in this dispute as Suffolk and the Beauforts were frequently granted large money and land grants from the king, as well as important government and military positions, redirecting much needed resources away from York's campaigns in France.

Suffolk eventually succeeded in having Humphrey of Gloucester arrested for treason. Humphrey died while awaiting trial in prison at Bury St Edmunds in 1447. Some authorities date the start of the War of the Roses from the death of Humphrey. At the same time, Richard of York was stripped of the prestigious military command in France and sent to govern the relatively distant Ireland, whereby he could not interfere in the proceedings of the court. However, with severe reverses in France, Suffolk was stripped of office and was murdered on his way to exile. Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset (Cardinal Beaufort's nephew), succeeded him as leader of the party seeking peace with France. The Duke of York meanwhile represented those who wished to prosecute the war more vigorously, and criticised the court, and Somerset in particular, for starving him of funds and men during his campaigns in France.

In all these quarrels, Henry VI had taken little part. He was seen as a weak, ineffectual king. Also, he displayed several symptoms of mental illness[29] that he may have inherited from his maternal grandfather, Charles VI of France. By 1450 many considered Henry incapable of carrying out the duties and responsibilities of a king.

In 1450, there was a violent popular revolt in Kent, Jack Cade's Rebellion, which is often seen as the prelude to the Wars of the Roses.[30] The rebel manifesto, The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent written under Cade's leadership, accused the crown of extortion, perversion of justice, and election fraud. The rebels occupied parts of London, and executed James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele, the unpopular Lord High Treasurer, after a hasty trial. After some of them fell to looting, they were driven out of London by the citizens. They dispersed after they were supposedly pardoned but several, including Cade, were later executed.[31] After the rebellion, the rebels' grievances formed the basis of Richard of York's opposition to a royal government from which he felt excluded.[30]

Two years later, in 1452, Richard of York returned to England from his new post as Lieutenant of Ireland and marched on London, demanding Somerset's removal and reform of the government. At this stage, few of the nobles supported such drastic action, and York was forced to submit to superior force at Blackheath. He was imprisoned for much of 1452 and 1453[32] but was released after swearing not to take arms against the court.

The increasing discord at court was mirrored in the country as a whole, where noble families engaged in private feuds and showed increasing disrespect for the royal authority and the courts of law. In many cases, feuds were fought between old-established families, and formerly minor nobility raised in power and influence by Henry IV in the aftermath of the rebellions against him. The quarrel between the Percys—long the Earls of Northumberland—and the comparatively upstart Nevilles was the best-known of these private wars and followed this pattern, as did the Bonville–Courtenay feud in Cornwall and Devon.[33] A factor in these feuds was the presence of large numbers of soldiers discharged from the English armies that had been defeated in France. Nobles engaged many of these to mount raids, or to pack courts of justice with their supporters, intimidating suitors, witnesses, and judges.

This growing civil discontent, the abundance of feuding nobles with private armies, and corruption in Henry VI's court formed a political climate ripe for civil war. With the king so easily manipulated, power rested with those closest to him at court, in other words, Somerset and the Lancastrian faction. Richard and the Yorkist faction, who tended to be physically placed further away from the seat of power, found their power slowly being stripped away. Royal power and finances also started to slip, as Henry was persuaded to grant many royal lands and estates to the Lancastrians, thereby losing their revenue.

In 1453, Henry suffered the first of several bouts of complete mental collapse, during which he failed even to recognise his new-born son, Edward of Westminster. On 22 March 1454, Cardinal John Kemp, the Chancellor, died. Henry was incapable of nominating a successor.[34] To ensure that the country could be governed, a Council of Regency was set up, headed by the Duke of York, who remained popular with the people, as Lord Protector. York soon asserted his power with ever-greater boldness (although there is no proof that he had aspirations to the throne at this early stage). He imprisoned Somerset and backed his Neville allies (his brother-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury, and Salisbury's son, the Earl of Warwick), in their continuing feud with the Earl of Northumberland, a powerful supporter of Henry.

Henry recovered in 1455 and once again fell under the influence of those closest to him at court. Directed by Henry's queen, the powerful and aggressive Margaret of Anjou, who emerged as the de facto leader of the Lancastrians, Richard was forced out of court. Margaret built up an alliance against Richard and conspired with other nobles to reduce his influence. An increasingly thwarted Richard (who feared arrest for treason) finally resorted to armed hostilities in 1455.

Early stages

Start of the war

Richard, Duke of York, led a small force toward London and was met by Henry's forces at St Albans, north of London, on 22 May 1455. The relatively small First Battle of St Albans was the first open conflict of the civil war. Richard's aim was ostensibly to remove "poor advisors" from King Henry's side. The result was a Lancastrian defeat. Several prominent Lancastrian leaders, including Somerset and Northumberland, were killed. After the battle, the Yorkists found Henry hiding in a local tanner's shop, abandoned by his advisers and servants, apparently having suffered another bout of mental illness. (He had also been slightly wounded in the neck by an arrow.)[35] York and his allies regained their position of influence. With the king indisposed, York was again appointed Protector, and Margaret was shunted aside, charged with the king's care.

For a while, both sides seemed shocked that an actual battle had been fought and did their best to reconcile their differences, but the problems that caused conflict soon re-emerged, particularly the issue of whether the Duke of York or Henry and Margaret's infant son, Edward, would succeed to the throne. Margaret refused to accept any solution that would disinherit her son, and it became clear that she would only tolerate the situation for as long as the Duke of York and his allies retained the military ascendancy.

Henry recovered and in February 1456 he relieved York of his office of Protector.[36] In the autumn of that year, Henry went on royal progress in the Midlands, where the king and queen were popular. Margaret did not allow him to return to London where the merchants were angry at the decline in trade and the widespread disorder. The king's court was set up at Coventry. By then, the new Duke of Somerset was emerging as a favourite of the royal court. Margaret persuaded Henry to revoke the appointments York had made as Protector, while York was made to return to his post as a lieutenant in Ireland.

Disorder in the capital and the north of England (where fighting between the Nevilles and Percys had resumed [37]) and piracy by French fleets on the south coast was growing, but the king and queen remained intent on protecting their positions, with the queen introducing conscription for the first time in England. Meanwhile, York's ally, Warwick (later dubbed "The Kingmaker"), was growing in popularity in London as the champion of the merchants; as Captain of Calais he had fought piracy in the Channel.[38]

In the spring of 1458, Thomas Bourchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury, attempted to arrange a reconciliation. The lords had gathered in London for a Grand Council and the city was full of armed retainers. The Archbishop negotiated complex settlements to resolve the blood-feuds that had persisted since the Battle of St. Albans. Then, on Lady Day (25 March), the King led a "love day" procession to St. Paul's Cathedral, with Lancastrian and Yorkist nobles following him, hand in hand.[37] No sooner had the procession and the Council dispersed than plotting resumed.

Act of Accord

The next outbreak of fighting was prompted by Warwick's high-handed actions as Captain of Calais. He led his ships in attacks on neutral Hanseatic League and Spanish ships in the Channel on flimsy grounds of sovereignty. He was summoned to London to face inquiries, but he claimed that attempts had been made on his life, and returned to Calais. York, Salisbury, and Warwick were summoned to a royal council at Coventry, but they refused, fearing arrest when they were isolated from their supporters.[39][40]

York summoned the Nevilles to join him at his stronghold at Ludlow Castle in the Welsh Marches. On 23 September 1459, at the Battle of Blore Heath in Staffordshire, a Lancastrian army failed to prevent Salisbury from marching from Middleham Castle in Yorkshire to Ludlow. Shortly afterward the combined Yorkist armies confronted the much larger Lancastrian force at the Battle of Ludford Bridge. Warwick's contingent from the garrison of Calais under Andrew Trollope defected to the Lancastrians, and the Yorkist leaders fled. York returned to Ireland, and his eldest son, Edward, Earl of March, Salisbury and Warwick fled to Calais.

The Lancastrians were back in total control. York and his supporters were attainted at the Parliament of Devils as traitors. Somerset was appointed Governor of Calais and was dispatched to take over the vital fortress on the French coast, but his attempts to evict Warwick were easily repulsed. Warwick and his supporters even began to launch raids on the English coast from Calais, adding to the sense of chaos and disorder. Being attainted, only by a successful invasion could the Yorkists recover their lands and titles. Warwick travelled to Ireland under the protection of Gaillard IV de Durfort, Lord of Duras,[41] to concert plans with York, evading the royal ships commanded by the Duke of Exeter.[42] In late June 1460, Warwick, Salisbury, and Edward of March crossed the Channel and rapidly established themselves in Kent and London, where they enjoyed wide support. Backed by a papal emissary who had taken their side, they marched north. King Henry led an army south to meet them while Margaret remained in the north with Prince Edward. At the Battle of Northampton on 10 July, the Yorkist army under Warwick defeated the Lancastrians, aided by treachery in the king's ranks. For the second time in the war, King Henry was found by the Yorkists in a tent, abandoned by his retinue, having suffered another breakdown. With the king in their possession, the Yorkists returned to London.

In the light of this military success, Richard of York moved to press his claim to the throne based on the illegitimacy of the Lancastrian line. Landing in the north Wales, he and his wife Cecily entered London with all the ceremony usually reserved for a monarch. Parliament was assembled, and when York entered he made straight for the throne, which he may have been expecting the Lords to encourage him to take for himself as they had acclaimed Henry IV in 1399. Instead, there was stunned silence. York announced his claim to the throne, but the Lords, even Warwick, and Salisbury, were shocked by his presumption; they had no desire at this stage to overthrow King Henry. Their ambition was still limited to the removal of his councillors.

The next day, York produced detailed genealogies to support his claim based on his descent from Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence. York's claim was through the daughter of a second son, Henry's through the son of a third son. The judges felt that Common law principles could not determine who had priority in the royal succession, and declared the matter "above the law and passed their learning."[43] Parliament agreed to consider the matter and accepted that York's claim was better, but by a majority of five, they voted that Henry VI should remain as king. A compromise was struck in October 1460 with the Act of Accord, which recognised York as Henry's successor, disinheriting Henry's six-year-old son, Edward. York accepted this compromise as the best offer. It gave him much of what he wanted, particularly since he was also made Protector of the Realm and was able to govern in Henry's name.

Death of Richard, Duke of York

Queen Margaret and her son had fled to the north of Wales, parts of which were still in Lancastrian hands. They later travelled by sea to Scotland to negotiate for Scottish assistance. Mary of Gueldres, Queen Consort to James II of Scotland, agreed to give Margaret an army on condition that she cede the town of Berwick to Scotland and Mary's daughter be betrothed to Prince Edward. Margaret agreed, although she had no funds to pay her army and could only promise booty from the riches of southern England, as long as no looting took place north of the River Trent.

The Duke of York left London later that year with the Earl of Salisbury to consolidate his position in the north against the Lancastrians who were reported to be massing near the city of York. He took up a defensive position at Sandal Castle near Wakefield over Christmas 1460. Then on 30 December, his forces left the castle and attacked the Lancastrians in the open, although outnumbered. The ensuing Battle of Wakefield was a complete Lancastrian victory. Richard of York was slain in the battle, and both Salisbury and York's 17-year-old second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, were captured and executed. Margaret ordered the heads of all three placed on the gates of York.

Middle stages

Edward's claim to the throne

The Act of Accord and the events of Wakefield left the 18-year-old Edward, Earl of March, York's eldest son, as Duke of York and heir to his claim to the throne. With an army from the pro-Yorkist Marches (the border area between England and Wales), he met Jasper Tudor's Lancastrian army arriving from Wales, and he defeated them soundly at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in Herefordshire. He inspired his men with a "vision" of three suns at dawn (a phenomenon known as "parhelion"), telling them that it was a portent of victory and represented the three surviving York sons; himself, George and Richard. This led to Edward's later adoption of the sign of the sunne in splendour as his personal device.

Margaret's army was moving south, supporting itself by looting as it passed through the prosperous south of England. In London, Warwick used this as propaganda to reinforce Yorkist support throughout the south – the town of Coventry switched allegiance to the Yorkists. Warwick's army established fortified positions north of the town of St Albans to block the main road from the north but was outmanoeuvred by Margaret's army, which swerved to the west and then attacked Warwick's positions from behind. At the Second Battle of St Albans, the Lancastrians won another big victory. As the Yorkist forces fled they left behind King Henry, who was found unharmed, sitting quietly beneath a tree.

Henry knighted thirty Lancastrian soldiers immediately after the battle. In an illustration of the increasing bitterness of the war, Queen Margaret instructed her seven-year-old son Edward of Westminster to determine the manner of execution of the Yorkist knights who had been charged with keeping Henry safe and had stayed at his side throughout the battle.

As the Lancastrian army advanced southwards, a wave of dread swept London, where rumours were rife about savage northerners intent on plundering the city. The people of London shut the city gates and refused to supply food to the queen's army, which was looting the surrounding counties of Hertfordshire and Middlesex.

Yorkist triumph

Edward of March, having joined with Warwick's surviving forces, advanced towards London from the west at the same time that the queen retreated northwards to Dunstable; as a result, Edward and Warwick were able to enter London with their army. They found considerable support there, as the city was largely Yorkist-supporting. It was clear that Edward was no longer simply trying to free the king from bad councillors, but that his goal was to take the crown. Thomas Kempe, the Bishop of London, asked the people of London their opinion and they replied with shouts of "King Edward". The request was quickly approved by Parliament, and Edward was unofficially appointed king in an impromptu ceremony at Westminster Abbey; Edward vowed that he would not have a formal coronation until Henry VI and his wife were removed from the scene. Edward claimed Henry had forfeited his right to the crown by allowing his queen to take up arms against his rightful heirs under the Act of Accord. Parliament had already accepted that Edward's victory was simply a restoration of the rightful heir to the throne.

Edward and Warwick marched north, gathering a large army as they went, and met an equally impressive Lancastrian army at Towton. The Battle of Towton, near York, was the biggest battle of the Wars of the Roses. Both sides agreed beforehand that the issue would be settled that day, with no quarter asked or given. An estimated 40,000–80,000 men took part, with over 20,000 men being killed during (and after) the battle, an enormous number for the time and the greatest recorded single day's loss of life on English soil. Edward and his army won a decisive victory, and the Lancastrians were routed, with most of their leaders slain. Henry and Margaret, who were waiting in York with their son Edward, fled north when they heard the outcome. Many of the surviving Lancastrian nobles switched allegiance to King Edward, and those who did not were driven back to the northern border areas and a few castles in Wales. Edward advanced to take York, where he replaced the rotting heads of his father, his brother, and Salisbury with those of defeated Lancastrian lords such as the notorious John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford of Skipton-Craven, who was blamed for the execution of Edward's brother Edmund, Earl of Rutland, after the Battle of Wakefield.

Edward IV

The official coronation of Edward IV took place on June 1461 in London, where he received a rapturous welcome from his supporters.

After the Battle of Towton, Henry VI and Margaret had fled to Scotland, where they stayed with the court of James III and followed through on their promise to cede Berwick to Scotland. Later in the year, they mounted an attack on Carlisle, but, lacking money, they were easily repulsed by Edward's men, who were rooting out the remaining Lancastrian forces in the northern counties. Several castles under Lancastrian commanders held out for years: Dunstanburgh, Alnwick (the Percy family seat), and Bamburgh were some of the last to fall.

There was also some fighting in Ireland. At the Battle of Piltown in 1462, the Yorkish supporter Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Desmond, defeated the Lancastrian Butlers of Kilkenny. The Butlers suffered more than 400 casualties. Local folklore claims that the battle was so violent that the local river ran red with blood, hence the names Pill River and Piltown (Baile an Phuill, meaning "Town of the blood").

There were Lancastrian revolts in the north of England in 1464. Several Lancastrian nobles, including the third Duke of Somerset, who had been reconciled to Edward, readily led the rebellion. The revolt was put down by Warwick's brother, John Neville. A small Lancastrian army was destroyed at the Battle of Hedgeley Moor on 25 April, but because Neville was escorting Scottish commissioners for a treaty to York, he could not immediately follow up this victory. Then on 15 May, he routed Somerset's army at the Battle of Hexham. Somerset was captured and executed.

The deposed King Henry was later captured for the third time at Clitheroe in Lancashire in 1465. He was taken to London and held prisoner at the Tower of London, where, for the time being, he was reasonably well treated. About the same time, once England under Edward IV and Scotland had come to terms, Margaret and her son were forced to leave Scotland and sail to France, where they maintained an impoverished court in exile for several years.[44] The last remaining Lancastrian stronghold was Harlech Castle in Wales, which surrendered in 1468 after a seven-year-long siege.

Warwick's rebellion and the death of Henry VI

The powerful Earl of Warwick ("the Kingmaker") had meanwhile become the greatest landowner in England. Already a great magnate through his wife's property, he had also inherited his father's estates and had been granted much forfeited Lancastrian property. He also held many of the offices of state. He was convinced of the need for an alliance with France and had been negotiating a match between Edward and a French bride. However, Edward had married Elizabeth Woodville, the widow of a Lancastrian knight, in secret in 1464. He later announced the news of his marriage as fait accompli, to Warwick's considerable embarrassment.

This embarrassment turned to bitterness when the Woodvilles came to be favoured over the Nevilles at court. Many of Queen Elizabeth's relatives were married into noble families and others were granted peerages or royal offices. Other factors compounded Warwick's disillusionment: Edward's preference for an alliance with Burgundy rather than France and reluctance to allow his brothers George, Duke of Clarence and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, to marry Warwick's daughters Isabel and Anne. Furthermore, Edward's general popularity was on the wane in this period with higher taxes and persistent disruptions of law and order.

By 1469, Warwick had allied with Edward's jealous and treacherous brother George, who married Isabel Neville in defiance of Edward's wishes in Calais. They raised an army that defeated the king's forces at the Battle of Edgecote Moor. Edward was captured at Olney, Buckinghamshire, and imprisoned at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire. (Warwick briefly had two Kings of England in his custody.) Warwick had the queen's father, Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers, and her brother John executed. However, he made no immediate move to have Edward declared illegitimate and place George on the throne.[45] The country was in turmoil, with nobles once again settling scores with private armies (in episodes such as the Battle of Nibley Green), and Lancastrians being encouraged to rebel.[46] Few of the nobles were prepared to support Warwick's seizure of power. Edward was escorted to London by Warwick's brother George Neville, the Archbishop of York, where he and Warwick were reconciled, to outward appearances.

When further rebellions broke out in Lincolnshire, Edward easily suppressed them at the Battle of Losecoat Field. From the testimony of the captured leaders, he declared that Warwick and George, Duke of Clarence, had instigated them. They were declared traitors and forced to flee to France, where Margaret of Anjou was already in exile. Louis XI of France, who wished to forestall a hostile alliance between Edward and Edward's brother-in-law Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, suggested the idea of an alliance between Warwick and Margaret. Neither of those two formerly mortal enemies entertained the notion at first, but eventually, they were brought round to realise the potential benefits. However, both were undoubtedly hoping for different outcomes: Warwick for a puppet king in the form of Henry VI or his young son; Margaret to be able to reclaim her family's realm. In any case, a marriage was arranged between Warwick's daughter Anne and Margaret's son Edward of Westminster, and Warwick invaded England in the autumn of 1470.

Edward IV had already marched north to suppress another uprising in Yorkshire. Warwick, with help from a fleet under his nephew, the Bastard of Fauconberg, landed at Dartmouth and rapidly secured support from the southern counties and ports. He occupied London in October and paraded Henry VI through the streets as the restored king. Warwick's brother John Neville, who had recently received the empty title Marquess of Montagu and who led large armies in the Scottish marches, suddenly defected to Warwick. Edward was unprepared for this event and had to order his army to scatter. He and Richard, Duke of Gloucester, fled from Doncaster to the coast and thence to Holland and exile in Burgundy. They were proclaimed traitors, and many exiled Lancastrians returned to reclaim their estates.

.jpg)

Warwick's success was short-lived, however. He over-reached himself with his plan to invade Burgundy in alliance with the King of France, tempted by King Louis' promise of territory in the Netherlands as a reward. This led Edward's brother-in-law, Charles of Burgundy, to provide funds and troops to Edward to enable him to launch an invasion of England in 1471. Edward landed with a small force at Ravenspur on the Yorkshire coast. Initially claiming to support Henry and to be seeking only to have his title of Duke of York restored, he soon gained the city of York and rallied several supporters. His brother George turned traitor again, abandoning Warwick. Having outmaneuvered Warwick and Montagu, Edward captured London. His army then met Warwick's at the Battle of Barnet. The battle was fought in thick fog, and some of Warwick's men attacked each other by mistake. It was believed by all that they had been betrayed, and Warwick's army fled. Warwick was cut down trying to reach his horse. Montagu was also killed in the battle.

Margaret and her son Edward had landed in the West Country only a few days before the Battle of Barnet. Rather than return to France, Margaret sought to join the Lancastrian supporters in Wales and marched to cross the Severn but was thwarted when the city of Gloucester refused her passage across the river. Her army, commanded by the fourth successive Duke of Somerset, was brought to battle and destroyed at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Her son Prince Edward, the Lancastrian heir to the throne, was killed. With no heirs to succeed him, Henry VI was murdered shortly afterward, on 21 May 1471, to strengthen the Yorkist hold on the throne.

Later stages

Richard III

The restoration of Edward IV in 1471 is sometimes seen as marking the end of the Wars of the Roses proper. Peace was restored for the remainder of Edward's reign. His youngest brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and Edward's lifelong companion and supporter, William Hastings, were generously rewarded for their loyalty, becoming effectively governors of the north and midlands respectively.[47] George of Clarence became increasingly estranged from Edward and was executed in 1478 for association with convicted traitors.

When Edward died suddenly in 1483, political and dynastic turmoil erupted again. Many of the nobles still resented the influence of the queen's Woodville relatives (her brother, Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers and her son by her first marriage, Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset), and regarded them as power-hungry upstarts ('parvenus'). At the time of Edward's premature death, his heir, Edward V, was only 12 years old and had been brought up under the stewardship of Earl Rivers at Ludlow Castle.

On his deathbed, Edward had named his surviving brother Richard of Gloucester as Protector of England. Richard had been in the north when Edward died. Hastings, who also held the office of Lord Chamberlain, sent word to him to bring a strong force to London to counter any force the Woodvilles might muster.[48] The Duke of Buckingham also declared his support for Richard.

Richard and Buckingham overtook Earl Rivers, who was escorting the young Edward V to London, at Stony Stratford in Buckinghamshire on 29 April. Although they dined with Rivers amicably, they took him prisoner the next day and declared to Edward that they had done so to forestall a conspiracy by the Woodvilles against his life. Rivers and his nephew Richard Grey were sent to Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire and executed there at the end of June.

Edward entered London in the custody of Richard on 4 May and was lodged in the Tower of London. Elizabeth Woodville had already gone hastily into the sanctuary at Westminster with her remaining children, although preparations were being made for Edward V to be crowned on 22 June, at which point Richard's authority as Protector would end. On 13 June, Richard held a full meeting of the Council, at which he accused Hastings and others of conspiracy against him. Hastings was executed without trial later in the day.

Thomas Bourchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury, then persuaded Elizabeth Woodville to allow her younger son, the 9-year-old Richard, Duke of York, to join Edward in the Tower. Having secured the boys, Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells then alleged that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville had been illegal and that the two boys were therefore illegitimate. Richard then claimed the crown as King Richard III. The two imprisoned boys, known as the "Princes in the Tower", disappeared and are assumed to have been murdered. There was never a trial or judicial inquest on the matter. Perkin Warbeck claimed he was the younger of the Princes from 1490 and was recognised as such by Richard's sister, the Duchess of Burgundy.

Having been crowned in a lavish ceremony on 6 July, Richard then proceeded on a tour of the Midlands and the north of England, dispensing generous bounties and charters and naming his son as the Prince of Wales.

Buckingham's revolt

Opposition to Richard's rule had already begun in the south when, on 18 October, the Duke of Buckingham (who had been instrumental in placing Richard on the throne and who himself had a distant claim to the crown) led a revolt aimed at installing the Lancastrian Henry Tudor. It has been argued that his supporting Tudor rather than either Edward V or his younger brother, showed Buckingham was aware that both were already dead.[49]

The Lancastrian claim to the throne had descended to Henry Tudor on the death of Henry VI and his son in 1471. Henry's father, Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, had been a half-brother of Henry VI, but Henry's claim to royalty was through his mother, Margaret Beaufort. She was descended from John Beaufort, who was a son of John of Gaunt and thus a grandson of Edward III. John Beaufort had been illegitimate at birth, though later legitimised by the marriage of his parents. It had supposedly been a condition of the legitimation that the Beaufort descendants forfeited their rights to the crown. Henry had spent much of his childhood under siege in Harlech Castle or exile in Brittany. After 1471, Edward IV had preferred to belittle Henry's pretensions to the crown and made only sporadic attempts to secure him. However, his mother, Margaret Beaufort, had been twice remarried, first to Buckingham's uncle, and then to Thomas, Lord Stanley, one of Edward's principal officers, and continually promoted her son's rights.

Buckingham's rebellion failed. Some of his supporters in the south rose up prematurely, thus allowing Richard's Lieutenant in the South, the Duke of Norfolk, to prevent many rebels from joining forces. Buckingham himself raised a force at Brecon in mid-Wales. He was prevented from crossing the River Severn to join other rebels in the south of England by storms and floods, which also prevented Henry Tudor landing in the West Country. Buckingham's starving forces deserted and he was betrayed and executed.

The failure of Buckingham's revolt was clearly not the end of the plots against Richard, who could never again feel secure, and who also suffered the loss of his wife and eleven-year-old son, putting the future of the Yorkist dynasty in doubt.

Henry VII

Many of Buckingham's defeated supporters and other disaffected nobles fled to join Henry Tudor in exile. Richard made an attempt to bribe the Duke of Brittany's chief Minister Pierre Landais to betray Henry, but Henry was warned and escaped to France, where he was again given sanctuary and aid.[50]

Confident that many magnates and even many of Richard's officers would join him, Henry set sail from Harfleur on 1 August 1485, with a force of exiles and French mercenaries. With fair winds, he landed in Pembrokeshire six days later and the officers Richard had appointed in Wales either joined Henry or stood aside. Henry gathered supporters on his march through Wales and the Welsh Marches and defeated Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Richard was slain during the battle, supposedly by the major Welsh landowner Rhys ap Thomas with a blow to the head from his poleaxe. Rhys was knighted three days later by Henry VII.

Henry, having been acclaimed King Henry VII, strengthened his position by marrying Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV and the second best surviving Yorkist claimant after George of Clarence's son the new duke of Warwick, reuniting the two royal houses. Henry merged the rival symbols of the red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of York into the new emblem of the red and white Tudor Rose. Henry later shored up his position by executing several other claimants, a policy his son Henry VIII continued.

Many historians consider the accession of Henry VII to mark the end of the Wars of the Roses. Others argue that they continued to the end of the fifteenth century, as there were several plots to overthrow Henry and restore Yorkist claimants. Only two years after the Battle of Bosworth, Yorkists rebelled, led by John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, who had been named by Richard III as his heir but had been reconciled with Henry after Bosworth. The conspirators produced a pretender, a boy named Lambert Simnel, who resembled the young Edward, Earl of Warwick (son of George of Clarence), the best surviving male claimant of the House of York. The imposture was shaky because the young earl was still alive and in King Henry's custody and was paraded through London to expose the impersonation. At the Battle of Stoke Field, Henry defeated Lincoln's army. Lincoln died in the battle. Simnel was pardoned for his part in the rebellion and was sent to work in the royal kitchens.

Henry's throne was challenged again in 1491, with the appearance of the pretender Perkin Warbeck, who claimed he was Richard, Duke of York (the younger of the two Princes in the Tower). Warbeck made several attempts to incite revolts, with support at various times from the court of Burgundy and James IV of Scotland. He was captured after the failed Second Cornish uprising of 1497 and killed in 1499, after attempting to escape from prison. Warwick was also executed, rendering the male-line of the House of York (and by extension the whole Plantagenet dynasty excluding the legitimized Beauforts who were later renamed to the House of Somerset) extinct.

During the reign of Henry VII's son Henry VIII, the possibility of a Yorkist challenge to the throne remained until as late as 1525, in the persons of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk and his brother Richard de la Pole, all of whom had blood ties to the Yorkist dynasty but were excluded by the pro-Woodville Tudor settlement. To an extent, England's break with Rome was prompted by Henry's fears of a disputed succession, should he leave only a female heir to the throne or an infant who would be as vulnerable as Henry VI had been to antagonistic or rapacious regents.

Aftermath

Historians debate the extent of impact the wars had on medieval English life. The classical view is that the many casualties among the nobility continued the changes in feudal English society caused by the effects of the Black Death. These included a weakening of the feudal power of the nobles and an increase in the power of the merchant classes and the growth of a centralised monarchy under the Tudors. The wars heralded the end of the medieval period in England and the movement towards the Renaissance. After the wars, the large standing baronial armies that had helped fuel the conflict were suppressed. Henry VII, wary of any further fighting, kept the barons on a very tight leash, removing their right to raise, arm and supply armies of retainers so that they could not make war on each other or the king. The military power of individual barons declined, and the Tudor court became a place where baronial squabbles were decided with the influence of the monarch.

Revisionists, such as the Oxford historian K. B. McFarlane, suggest that the effects of the conflicts have been greatly exaggerated and that there were no wars of the roses.[51] Many places were unaffected by the wars, particularly in the eastern part of England, such as East Anglia.[52] It has also been suggested that the traumatic impact of the wars was exaggerated by Henry VII, to magnify his achievement in quelling them and bringing peace. The effect of the wars on the merchant and labouring classes was far less than in the long-drawn-out wars of siege and pillage in Europe, which were carried out by mercenaries who profited from long wars. Although there were some lengthy sieges, such as those of Harlech Castle and Bamburgh Castle, these were in comparatively remote and less populous regions. In the populated areas, both factions had much to lose by the ruin of the country and sought a quick resolution of the conflict by pitched battle.[53] Philippe de Commines observed in 1470:

The realm of England enjoys one favour above all other realms, that neither the countryside nor the people are destroyed, nor are buildings burnt or demolished. Misfortune falls on soldiers and nobles in particular...[54]

Exceptions to this claimed general rule were the Lancastrian looting of Ludlow after the largely bloodless Yorkist defeat at Ludford Bridge in 1459, and the widespread pillaging carried out by Queen Margaret's unpaid army as it advanced south in early 1461. Both events inspired widespread opposition to the Queen, and support for the Yorkists.

Many areas did little or nothing to change their city defences, perhaps an indication that they were left untouched by the wars. City walls were either left in their ruinous state or only partially rebuilt. In the case of London, the city was able to avoid being devastated by convincing the York and Lancaster armies to stay out after the inability to recreate the defensive city walls.[55]

Few noble houses were extinguished during the wars; in the period from 1425 to 1449, before the outbreak of the wars, there were as many extinctions of noble lines from natural causes (25) as occurred during the fighting (24) from 1450 to 1474.[56] The most ambitious nobles died and by the later period of the wars, fewer nobles were prepared to risk their lives and titles in an uncertain struggle.

The kings of France and Scotland and the dukes of Burgundy played the two factions off against each other, pledging military and financial aid and offering asylum to defeated nobles and pretenders, to prevent a strong and unified England from making war on them.

In literature

Chronicles written during the Wars of the Roses include:

- Benet's Chronicle

- Gregory's Chronicle (1189–1469)

- Short English Chronicle (before 1465)

- Hardyng's Chronicle: first version for Henry VI (1457)

- Hardyng's Chronicle: second version for Richard, duke of York and Edward IV (1460 and c. 1464)

- Hardyng's Chronicle: second "Yorkist" version revised for Lancastrians during Henry VI's Readeption (see Peverley's article).

- Capgrave (1464)

- Commynes (1464–98)

- Chronicle of the Lincolnshire Rebellion (1470)

- Historie of the arrival of Edward IV in England (1471)

- Waurin (before 1471)

- An English Chronicle: AKA Davies' Chronicle (1461)

- Brief Latin Chronicle (1422–71)

- Fabyan (before 1485)

- Rous (1480/86)

- Croyland Chronicle (1449–1486)

- Warkworth's Chronicle (1500?)

Key figures

_(14762567804).jpg)

- Kings of England

- Henry VI (Lancastrian)

- Edward IV (Yorkist)

- Edward V (Yorkist)

- Richard III (Yorkist)

- Henry VII (Tudor of Lancastrian ancestry, married the Yorkist heiress)

- Prominent antagonists 1455–87

- Yorkist

- Elizabeth Woodville Queen consort of Edward IV

- Anne Neville, Queen consort of Richard III

- Jacquetta Woodville, Lady Rivers, Mother of Elizabeth Woodville and mother-in-law of Edward IV

- George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV and Richard III

- Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

- Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick ('The Kingmaker')

- Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury

- John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu

- William Neville, 1st Earl of Kent

- Bastard of Fauconberg

- William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke

- William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings

- John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk

- Lancastrian

- Margaret of Anjou Queen consort of Henry VI

- Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, mother of Henry VII

- Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter

- Sir Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland

- Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland

- Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick ('The Kingmaker'), formerly a Yorkist and father of Queen Anne

- Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset

- Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset

- Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset

- John Clifford, 9th Baron de Clifford

- Jasper Tudor, 1st Duke of Bedford, half-brother of Henry VI

- John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

- Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham

- Yorkist

Family tree

The above-listed individuals with well-defined sides are coloured with red borders for Lancastrians and blue for Yorkists (The Kingmaker, his relatives and George Plantagenet changed sides, so they are represented with a purple border)

| Edward III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edmund of Langley [note 1] | Edward the Black Prince [note 2] | Lionel of Antwerp [note 3] | John of Gaunt [note 4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard II | Philippa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Roger Mortimer | Elizabeth Mortimer | Joan Beaufort | Henry IV Bolingbroke | John Beaufort | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard of Conisburgh | Anne Mortimer | Henry Percy | Eleanor Neville | Richard Neville | William Neville | Henry V | Catherine of Valois | Owen Tudor | John Beaufort | Edmund Beaufort | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard Plantagenet | Cecily Neville | Henry Percy | Richard Neville | John Neville | Thomas Neville | Margaret of Anjou | Henry VI | Edmund Tudor | Margaret Beaufort | Henry Beaufort | Edmund Beaufort | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edward IV | George Plantagenet | Isabel Neville | Richard III | Anne Neville | Edward of Westminster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edward V | Elizabeth of York | Henry VII Tudor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tudor dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Fourth son. Thomas of Woodstock being the youngest

- Firstborn son

- Second son

- Third son

The hinge point in the succession dispute is the forced abdication of Richard II and whether it was lawful or not. Following that event, Richard's legitimate successor would be Henry Bolingbroke if strict Salic inheritance were adhered to, or Anne Mortimer if male-preference primogeniture, which eventually became the standard form of succession (until the Succession to the Crown Act 2013), were adhered to.

Armies and warfare

Following defeat in the Hundred Years' War, English landowners complained vociferously about the financial losses resulting from the loss of their continental holdings; this is often considered a contributory cause of the Wars of the Roses.[60] The wars were fought largely by the landed aristocracy and armies of feudal retainers, with some mercenaries.

At the end of the Hundred Years' War, large numbers of unemployed soldiery returned to England seeking employment in the growing armies of the local nobility. England drifted toward misrule and violence under the weak governance as local noble families like the Nevilles and Percies increasingly relied on their feudal retainers to settle disputes. It became common practice for landowners to bind their mesnie knights to their service with annual payments.[61]

Edward III had developed the contract system where the monarch entered into formal written contracts called indenture with experienced captains who were contractually obliged to provide an agreed-upon number of men, at established rates for a given period. Frequently the landed nobility acted the principal or main contractor. Knights, men at arms and archers were often sub-contracted.[61] A lord could find men amongst his tenantry who included landless men and others who would crave the security of maintenance and livery. Skilled archers could command as high a wage as knights.[62] As baronial armies grew in size, the rule of law was weakened.

Support for each house largely depended upon dynastic factors, such as blood relationships, marriages within the nobility and the grants or confiscations of feudal titles and lands. Given the conflicting loyalties of blood, marriage, and ambition, it was not uncommon for nobles to switch sides; several battles (such as Northampton and Bosworth) were decided by treachery.. The armies consisted of nobles' contingents of men-at-arms, with companies of archers and foot-soldiers (such as billmen). There were sometimes contingents of foreign mercenaries, armed with cannon or handguns. The horsemen were generally restricted to "prickers" and "scourers"; i.e. scouting and foraging parties.

Much like their campaigns in France, it was customary for the English gentry to fight entirely on foot.[63] In several cases, noblemen dismounted and fought amongst the common foot-soldiers to both inspire them and due to the fact that, as proven by the experiences of battles on the continent, heavy cavalry is of limited tactical value when both sides possess large numbers of skilled Longbowmen.

It was often claimed that the nobles faced greater risks than the ordinary soldiers as there was little incentive for anyone to take prisoner any high-ranking noble during or immediately after a battle. During the Hundred Years' War against France, a captured noble would be able to ransom himself for a large sum but in the Wars of the Roses, a captured noble who belonged to a defeated faction had a high chance of being executed as a traitor. Forty-two captured knights were executed after the Battle of Towton.[64] The Burgundian observer Philippe de Commines, who met Edward IV in 1470, reported,

King Edward told me in all the battles which he had won, as soon as he had gained a victory, he mounted his horse and shouted to his men that they must spare the common soldiers and kill the lords, of whom none or few escaped.[54]

Even those who escaped execution might be declared attainted therefore possess no property and be of no value to a captor.[65]

Chronological list of battles

- First Battle of St Albans (22 May 1455)

- Battle of Blore Heath (23 September 1459)

- Battle of Ludford Bridge (12 October 1459)

- Battle of Sandwich (15 January 1460)

- Battle of Northampton (10 July 1460)

- Battle of Worksop (16 December 1460)

- Battle of Wakefield (30 December 1460)

- Battle of Mortimer's Cross (2 February 1461)

- Second Battle of St Albans (17 February 1461)

- Battle of Ferrybridge (28 March 1461)

- Battle of Towton (29 March 1461)

- Battle of Piltown (early 1462)

- Battle of Hedgeley Moor (25 April 1464)

- Battle of Hexham (15 May 1464)

- Battle of Edgecote Moor (26 July 1469)

- Battle of Losecoat Field (12 March 1470)

- Battle of Barnet (14 April 1471)

- Battle of Tewkesbury (4 May 1471)

- Battle of Bosworth Field (22 August 1485)

- Battle of Stoke Field (16 June 1487)

See also

References

- Wagner & Schmid 2011.

- Guy 1990, a leading comprehensive survey

- McCaffrey 1984.

- Later defected to the Lancastrians.

- Grummitt 2012, pp. xviii–xxi.

- Goodwin 2012, p. xix.

- During Shakespeare's time people used the term Civil Wars: cf. e.g., the title of Samuel Daniel's work, the First Four Books of the Civil Wars

- Goodwin 2012, p. xxi.

- Boutell 1914, p. 228.

- Cokayne 1910, pp. 240–241.

- Bellamy 1989, p. 19.

- Boutell 1914, p. 229.

- Boutell 1914, p. 26.

- Rowse 1966, p. 109.

- Abels, Richard (2002). "Royal Succession and the Growth of Political Stability in Ninth-Century Wessex". The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. 12: 92. ISBN 1 84383 008 6.

- Wagner 2001, p. 206.

- Mortimer 2006, p. 320.

- Saul 2005, pp. 153–154.

- Bennett 1998, p. 584.

- Bennett 1998, pp. 584–585.

- Rowse 1966, pp. 14–24.

- Mortimer 2007, appendix 2.

- Seward 1995, p. 39.

- Wagner 2001, p. 141.

- Griffiths 1968, p. 589.

- Royle 2009, pp. 160–161.

- Goodwin 2012, p. 20.

- Goodwin 2012, p. 34.

- Goodwin 2012, pp. 60–70.

- Wagner 2001, p. 133.

- Rowse 1966, pp. 123–124.

- Rowse 1966, p. 125.

- Royle 2009, pp. 207–208.

- Goodwin 2012, pp. 63–64.

- Farquhar 2001, p. 131.

- Rowse 1966, p. 136.

- Rowse 1966, p. 138.

- Pollard, A.J. (2007). Warwick the Kingmaker, London, pp. 177–178

- Rowse 1966, p. 139.

- Royle 2009, pp. 239–240.

- Guilhamon, Henri (1976). La Maison de Durfort au Moyen Age. p. 285.

- Rowse 1966, p. 140.

- Bennett 1998, pp. 580.

- Rowse 1966, pp. 155–156.

- Rowse 1966, p. 162.

- Baldwin 2002, p. 43.

- Baldwin 2002, p. 56.

- Rowse 1966, p. 186.

- Rowse 1966, p. 199.

- Rowse 1966, p. 212.

- "BBC War of the Roses discussion". In our Time Radio 4. 18 May 2000. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Redstone, Vincent B. (1902). "Social Conditions of England during the Wars of the Roses" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. New Series. 16 (1): 159–200. doi:10.2307/3678121.

- Sadler 2011, p. 14.

- Wise & Embleton, p.4

- Lander 1980, pp. 363–365.

- Terence Wise and G.A. Embleton, The Wars of the Roses, Osprey Men-at-Arms series, p. 4, from K.B. MacFarlane, The Nobility of Later Medieval England, Oxford University Press

- Alchin, Linda. "Lords and Ladies". King Henry II. Lords and Ladies, n.d. Web. 6 February 2014. http://www.lordsandladies.org/king-henry-ii.htm.

- Barrow, Mandy. "Timeline of the Kings and Queens of England: The Plantagenets". Project Britain: British Life and Culture. Mandy Barrow, n.d. Web. 6 February 2014. http://projectbritain.com/monarchy/angevins.html.

- Needham, Mark. "Family tree of Henry (II, King of England 1154–1189)". TimeRef.com. TimeRef.com, n.d. Web. 6 February 2014. http://www.timeref.com/tree68.htm.

- Webster, Bruce. Wars of the Roses. p. 40. Luminarium: Encyclopedia Project: "Every version of the complaints put forward by the rebels in 1450 harps on the losses in France."

- Sadler 2000, p. 3.

- Sadler 2000, p. 4.

- Ingram, Mike (2012). Bosworth 1485: Battle Story. The History Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7524-6988-1.

- Sadler 2011, p. 124.

- Sadler 2011, pp. 9, 14–15.

Bibliography

- Baldwin, D. (2002). Elizabeth Woodville. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2774-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bellamy, John G. (1989). Bastard Feudalism and the Law. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-71290-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bennett, Michael (1 June 1998). "Edward III's Entail and the Succession to the Crown, 1376–1471". The English Historical Review. 113 (452): 580–609.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boutell, C. (1914). A.C. Fox-Davies (ed.). The Handbook to English Heraldry (11th ed.). London: Reeves & Turner. OCLC 2034334.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cokayne, G. (1910). V. Gibbs (ed.). The Complete Peerage. 1. London: St. Catherine Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasury of Royal Scandals. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-7394-2025-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, George (16 February 2012). Fatal Colours. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2817-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, R.A. (1968). "Local Rivalries and National Politics: The Percies, the Nevilles, and the Duke of Exeter, 1452–55". Speculum. 43 (4): 589–632.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grummitt, David (30 October 2012). A Short History of the Wars of the Roses. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-875-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guy, J. (1990). Tudor England (paperback ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285213-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haigh, P. (1995). The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses. ISBN 0-7509-0904-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hicks, M. (20 April 2003). The Wars of the Roses 1455–1485 (PDF). Essential Histories. 54. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-491-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lander, J.R. (1980). Government and Community: England, 1450–1509. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-35794-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCaffrey, W. (1984). "Recent Writings on Tutor History". In Richard Schlatter (ed.). Recent Views on British History. Rutgers University Press. pp. 1–34. ISBN 978-0-8135-0959-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mortimer, I. (20 June 2006). "Richard II and the Succession to the Crown". History. 91 (3, 303): 320–336. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2006.00368.x. JSTOR 24427962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mortimer, Ian (2007). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-07300-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peverley, Sarah L. (2004). "66:1". Adapting to Readeption in 1470–1471: The Scribe as Editor in a Unique Copy of John Hardyng's Chronicle of England (Garrett MS. 142). The Princeton University Library Chronicle. pp. 140–172.

- Pollard, A.J. (1988). The Wars of the Roses. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-333-40603-6.

- Redstone, Vincent B. (1902). "Social Conditions of England during the Wars of the Roses" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. New Series. 16 (1): 159–200. doi:10.2307/3678121.

- Rowse, A.L. (1966). Bosworth Field & the Wars of the Roses. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-85326-691-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royle, Trevor (2009). The Road to Bosworth Field. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-72767-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadler, John (2011). Towton: The Battle of Palm Sunday Field 1461. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-965-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadler, John (2000). Armies and Warfare During the Wars of the Roses. Bristol: Stuart Press. ISBN 978-1-85804-183-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saul, Nigel (2005). The Three Richards: Richard I, Richard II and Richard III. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1852855215.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)