Battle of Towton

The Battle of Towton was fought on 29 March 1461 during the English Wars of the Roses, near the village of Towton in Yorkshire. It was "probably the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil".[1] An estimated 50,000 soldiers fought for hours amidst a snowstorm on that day, which was Palm Sunday. It brought about a change of monarchs in England, with Edward IV displacing Henry VI, establishing the House of York on the English throne and driving the incumbent House of Lancaster and its key supporters out of the country.

| Battle of Towton | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Roses | |||||||

The battle as depicted by Richard Caton Woodville Jr., 1922 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Modern estimate: 50,000 men | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 800 - 8,000 killed | Around 9,000 - 20,000 killed | ||||||

The incumbent King of England, Henry VI, on the throne since 1422, was a weak, ineffectual, and mentally unsound ruler, which encouraged the nobles to scheme for control over him. The situation deteriorated in the 1450s into a civil war between the supporters of his queen, Margaret of Anjou, and those of his cousin Richard, Duke of York. In 1460, the English parliament passed an act to let York succeed Henry as king. The queen refused to accept the dispossession of her own son's right to the throne and succeeded in raising a large army of supporters, who then promptly defeated and killed York in battle. The late duke's supporters considered the Lancastrians to have reneged on the parliamentary act of succession – a legal agreement – and York's son and heir, Edward, found enough backing to denounce Henry and declare himself king. The Battle of Towton was to affirm the victor's right to rule over England through force of arms.

On reaching the battlefield, the Yorkists found themselves heavily outnumbered. Part of their force under the Duke of Norfolk had yet to arrive. The Yorkist leader Lord Fauconberg turned the tables by ordering his archers to take advantage of the strong wind to outrange their enemies. The one-sided missile exchange, with Lancastrian arrows falling short of the Yorkist ranks, provoked the Lancastrians into abandoning their defensive positions. The ensuing hand-to-hand combat lasted hours, exhausting the combatants. The arrival of Norfolk's men reinvigorated the Yorkists and, encouraged by Edward, they routed their foes. Many Lancastrians were killed while fleeing; some trampled each other and others drowned in the rivers, which are said to have run red with blood for several days. Several who were taken as prisoners were executed.

The power of the House of Lancaster was severely reduced after this battle. Henry fled the country, and many of his most powerful followers were dead or in exile after the engagement, leaving a new king, Edward IV, to rule England. Later generations remembered the battle as depicted in William Shakespeare's dramatic adaptation of Henry's life – Henry VI, Part 3, Act 2, Scene 5. In 1929, the Towton Cross was erected on the battlefield to commemorate the event. Various archaeological remains and mass graves related to the battle were found in the area centuries after the engagement.

Setting

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

In 1461, England was in the sixth year of the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster over the English throne. The Lancastrians backed the reigning King of England, Henry VI, an indecisive man who had bouts of madness.[2] The leader of the Yorkists was initially Richard, Duke of York, who resented the dominance of a small number of aristocrats favoured by the king, principally his close relatives, the Beaufort family. Fuelled by rivalries between influential supporters of both factions, York's attempts to displace Henry's favourites from power led to war.[2][3] After capturing Henry at the Battle of Northampton in 1460, the duke, who was of royal blood, issued his claim to the throne. Even York's closest supporters among the nobility were reluctant to usurp the dynasty; the nobles passed by a majority vote the Act of Accord, which ruled that the duke and his heirs would succeed the throne upon Henry's death.[4][5]

The Queen of England, Margaret of Anjou, refused to accept an arrangement that deprived her son—Edward of Westminster—of his birthright. She had fled to Scotland after the Yorkist victory at Northampton; there she began raising an army, promising her followers the freedom to plunder on the march south through England. Her Lancastrian supporters also mustered in the north of England, preparing for her arrival. York marched with his army to meet this threat but he was lured into a trap at the Battle of Wakefield and killed. The duke and his second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland were decapitated by the Lancastrians and their heads were impaled on spikes atop the Micklegate Bar, a gatehouse of the city of York.[6] The leadership of the House of York passed onto the duke's heir, Edward.[7]

The victors of Wakefield were joined by Margaret's army and they marched south, plundering settlements in their wake. They liberated Henry after defeating the Yorkist army of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, in the Second Battle of St Albans and continued pillaging on their way to London. The city of London refused to open its gates to Henry and Margaret for fear of being looted. The Lancastrian army was short of supplies and had no adequate means to replenish them. When Margaret learned that Richard of York's eldest son Edward, Earl of March and his army had won the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in Herefordshire and were marching towards London, she withdrew the Lancastrians to York.[8][9] Warwick and the remnants of his army marched from St Albans to join Edward's men and the Yorkists were welcomed into London. Having lost custody of Henry, the Yorkists needed a justification to continue the rebellion against the king and his Lancastrian followers. On 4 March, Warwick proclaimed the young Yorkist leader as King Edward IV. The proclamation gained greater acceptance than Richard of York's earlier claim, as several nobles opposed to letting Edward's father ascend the throne viewed the Lancastrian actions as a betrayal of the legally established Accord.[10][11]

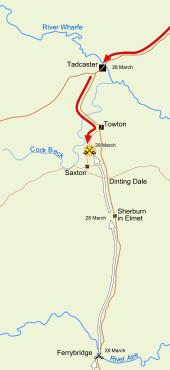

The country now had two kings—a situation that could not be allowed to persist, especially if Edward were to be formally crowned.[11] Edward offered amnesty to any Lancastrian supporter who renounced Henry. The move was intended to win over the commoners; his offer did not extend to wealthy Lancastrians (mostly the nobles).[12] The young king summoned and ordered his followers to march towards York to take back his family's city and to formally depose Henry through force of arms.[13] The Yorkist army moved along three routes. Warwick's uncle, Lord Fauconberg, led a group to clear the way to York for the main body, which was led by Edward. The Duke of Norfolk was sent east to raise forces and rejoin Edward before the battle. Warwick's group moved to the west of the main body, through the Midlands, gathering men as they went. On 28 March, the leading elements of the Yorkist army came upon the remains of the crossing in Ferrybridge that spanned the River Aire. They were rebuilding the bridge when they were attacked and routed by a band of about 500 Lancastrians, led by Lord Clifford.[14]

Learning of the encounter, Edward led the main Yorkist army to the bridge and was forced into a gruelling battle; although the Yorkists were superior in numbers, the narrow bridge was a bottleneck, forcing them to confront Clifford's men on equal terms. Edward sent Fauconberg and his horsemen to ford the river at Castleford, which should have been guarded by Henry Earl of Northumberland but he arrived late, by which time the Yorkists had crossed the ford and were heading to attack the Lancastrians at Ferrybridge from the flank. The Lancastrians retreated but were chased to Dinting Dale where they were all killed; Clifford was slain by an arrow to his throat. Having cleared the vicinity of enemy forces, the Yorkists repaired the bridge and pressed onwards to camp overnight at Sherburn-in-Elmet. The Lancastrian army marched to Tadcaster, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Towton and made camp.[15] As dawn broke, the two rival armies struck camp under dark skies and strong winds.[16][17] Although it was Palm Sunday, a day of holy significance to Christians, the forces prepared for battle and a few documents named the engagement the Battle of Palme Sonday Felde but the name did not gain wide acceptance.[18] Popular opinion favoured naming the battle after the village of Towton because of its proximity and it being the most prominent in the area.[19]

Force compositions

Contemporary sources like William Gregory's Chronicle of London claim the two armies were huge, with estimates ranging up to 200,000.[20] Historians believe a combined figure of around 50,000 is likely, approximately one to two percent of the English population at the time.[21][22] An analysis of 50 skeletons found in mass graves between 1996 and 2003 showed most were 24 to 30 years old, and many were veterans of previous engagements.[23]

Henry's physical and mental frailty was a major weakness for the Lancastrian cause, and he remained in York with Margaret.[22] In contrast, the 18-year-old Edward was a tall and imposing sight in armour, who led from the front; his preference for bold offensive tactics determined the Yorkist plan of action for this engagement. His presence and example was crucial to ensuring the Yorkists held together through the long and exhausting struggle.[16]

Approximately three-quarters of English peers fought in the battle;[22] eight were with the Yorkist army, whereas the Lancastrians had at least nineteen.[24] Historian Nigel H. Jones argues the disparity demonstrates the semi-religious power of an anointed medieval king, however incapable, to command the unquestioning fidelity of his subjects".[25]

Of the other Yorkist leaders, Warwick was absent from the battle, having suffered a leg wound at Ferrybridge.[26] Norfolk was too old to participate and his contingent was commanded by Walter Blount and Robert Horne; this may have been an advantage, since he was regarded as an unpredictable ally.[27] Edward relied heavily on Warwick's uncle, Lord Fauconberg, a veteran of the Anglo-French wars, highly regarded by contemporaries for his military skills.[28] He demonstrated this in a wide range of roles, having captained the Calais garrison,[28] led naval piracy expeditions in the Channel,[29] and commanded the Yorkist vanguard at Northampton.[30]

The senior Lancastrian general was Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, an experienced leader credited with victories at Wakefield and St Albans, although others suggest they were due to Sir Andrew Trollope. [31] Trollope was an extremely experienced and astute commander, who served under Warwick in Calais, before defecting to the Lancastrians at Ludford Bridge in 1459.[32] Other notable Lancastrian leaders included Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter,[33] and northern magnates the Earl of Northumberland,[34] Lord de Ros and Ralph Dacre. Another leading Lancastrian, Lord Clifford, was killed by an arrow in the throat at Ferrybridge.[35]

Deployment

Very few historical sources give detailed accounts of the battle and they do not describe the exact deployments of the armies. The paucity of such primary sources led early historians to adopt Hall's chronicle as their main resource for the engagement, despite its authorship 70 years after the event and questions over the origin of his information. The Burgundian chronicler Jean de Waurin (c. 1398 – c. 1474) was a more contemporary source, but his chronicle was made available to the public only from 1891, and several mistakes in it discouraged historians at that time from using it. Later reconstructions of the battle were based on Hall's version, supplemented by minor details from other sources.[36][37]

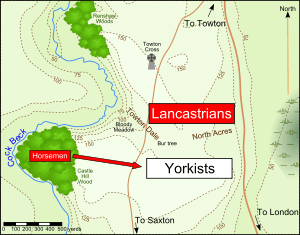

The battle took place on a plateau between the villages of Saxton (to the south) and Towton (to the north). The region was agricultural land, with plenty of wide open areas and small roads on which to manoeuvre the armies.[38] Two roads ran through the area: the Old London Road, which connected Towton to the English capital, and a direct road between Saxton and Towton. The steeply banked Cock Beck flowed in an S-shaped course around the plateau from the north to west. The plateau was bisected by the Towton Dale, which ran from the west and extended into the North Acres in the east. Woodlands were scattered along the beck; Renshaw Woods lined the river on the north-western side of the plateau, and south of Towton Dale, Castle Hill Wood grew on the west side of the plateau at a bend in the beck. The area to the north-east of this forest would be known as Bloody Meadow after the battle.[39]

According to Gravett and fellow military enthusiast Trevor James Halsall, Somerset's decision to engage the Yorkist army on this plateau was sound. Defending the ground just before Towton would block any enemy advance towards the city of York, whether they moved along the London–Towton road or an old Roman road to the west. The Lancastrians deployed on the north side of the dale, using the valley as a "protective ditch";[40][41] the disadvantage of this position was that they could not see beyond the southern ridge of the dale.[42] The Lancastrian flanks were protected by marshes; their right was further secured by the steep banks of the Cock Beck. The width of their deployment area did not allow for a longer front line, depriving the Lancastrians of the opportunity to use their numerical superiority.[40] Waurin's account gave rise to the suggestion that Somerset ordered a force of mounted spearmen to conceal itself in Castle Hill Wood, ready to charge into the Yorkist left flank at an opportune time in battle.[43]

The Yorkists appeared as the Lancastrians finished deployment. Line after line of soldiers crested the southern ridge of the dale and formed up in ranks opposite their enemies as snow began to fall. Edward's army was outnumbered and Norfolk's troops had yet to arrive to join them.

The Lancastrian army was organised in three divisions. The Duke of Somerset, as the overall commander of the whole force, headed the main division in the center alongside the Duke of Exeter. The right-wing was commanded by the Earl of Northumberland, whereas the left division was led by the Earl of Devon and Lord Dacre.[25]

Fighting

As Somerset was content to stand and let his foes come to him, the opening move of the battle was made by the Yorkists.[44] Noticing the direction and strength of the wind, Fauconberg ordered all Yorkist archers to step forward and unleash a volley of their arrows from what would be the standard maximum range of their longbows. With the wind behind them, the Yorkist missiles travelled farther than usual, plunging deep into the masses of soldiers on the hill slope.

The response from the Lancastrian archers was ineffective as the heavy wind blew snow in their faces. They found it difficult to judge the range and pick out their targets and their arrows fell short of the Yorkist ranks; Fauconberg had ordered his men to retreat after loosing one volley, thus avoiding any casualties. Unable to observe their results, the Lancastrians loosed their arrows until most had been used, leaving a thick, prickly carpet in the ground in front of the Yorkists.[16][45]

After the Lancastrians had ceased loosing their arrows, Fauconberg ordered his archers to step forward again to shoot. When they had exhausted their ammunition, the Yorkists plucked arrows off the ground in front of them—arrows loosed by their foes—and continued loosing. Coming under attack without any effective response of its own, the Lancastrian army moved from its position to engage the Yorkists in close combat. Seeing the advancing mass of men, the Yorkist archers shot a few more volleys before retreating behind their ranks of men-at-arms, leaving thousands of arrows in the ground to hinder the Lancastrian attack.[16][46]

As the Yorkists reformed their ranks to receive the Lancastrian charge, their left flank came under attack by the horsemen from Castle Hill Wood mentioned by Waurin. The Yorkist left wing fell into disarray and several men started to flee. Edward had to take command of the left wing to save the situation. By engaging in the fight and encouraging his followers, his example inspired many to stand their ground. The armies clashed and archers shot into the mass of men at short range. The Lancastrians continuously threw fresher men into the fray and gradually the numerically inferior Yorkist army was forced to give ground and retreat up the southern ridge. Gravett thought that the Lancastrian left had less momentum than the rest of its formation, skewing the line of battle such that its western end tilted towards Saxton.[47][48]

The fighting continued for three hours, according to research by English Heritage, a government body in charge of conservation of historic sites.[16][48] It was indecisive until the arrival of Norfolk's men. Marching up the Old London Road, Norfolk's contingent was hidden from view until they crested the ridge and attacked the Lancastrian left flank.[48][49] The Lancastrians continued to give fight but the advantage had shifted to the Yorkists. By the end of the day, the Lancastrian line had broken up, as small groups of men began fleeing for their lives.[16] Polydore Vergil, chronicler for Henry VII of England, claimed that combat lasted for a total of 10 hours.[50]

Rout

The tired Lancastrians flung off their helmets and armour to run faster. Without such protection, they were much more vulnerable to the attacks of the Yorkists. Norfolk's troops were much fresher and faster. Fleeing across what would later become known as Bloody Meadow, many Lancastrians were cut down from behind or were slain after they had surrendered. Before the battle, both sides had issued the order to give no quarter and the Yorkists were in no mood to spare anyone after the long, gruelling fight.[51] A number of Lancastrians, such as Trollope, also had substantial bounties on their heads.[12] Gregory's chronicle stated 42 knights were killed after they were taken prisoner.[16]

Archaeological findings in the late 20th century shed light on the final moments of the battle. In 1996 workmen at a construction site in the town of Towton uncovered a mass grave, which archaeologists believed to contain the remains of men who were slain during or after the battle in 1461. The bodies showed severe injuries to their upper torsos; arms and skulls were cracked or shattered.[52] One exhumed specimen, known as Towton 25, had the front of his skull bisected: a weapon had slashed across his face, cutting a deep wound that split the bone. The skull was also pierced by another deep wound, a horizontal cut from a blade across the back.[53]

The Lancastrians lost more troops in their rout than from the battlefield. Men struggling across the river were dragged down by currents and drowned. Those floundering were stepped on and pushed under water by their comrades behind them as they rushed to get away from the Yorkists. As the Lancastrians struggled across the river, Yorkist archers rode to high vantage points and shot arrows at them. The dead began to pile up and the chronicles state that the Lancastrians eventually fled across these "bridges" of bodies.[16][54] The chase continued northwards across the River Wharfe, which was larger than Cock Beck. A bridge over the river collapsed under the flood of men and many drowned trying to cross. Those who hid in Tadcaster and York were hunted down and killed.[55]

A newsletter dated 4 April 1461 reported a widely circulated figure of 28,000 casualties in the battle, which Charles Ross and other historians believe was exaggerated. The number was taken from the heralds' estimate of the dead and appeared in letters from Edward and the Bishop of Salisbury, Richard Beauchamp.[16][56] Letters from an ambassador and a merchant from the duchy of Milan broke this number down into 8,000 dead for the Yorkists and 20,000 for the Lancastrians;[57] on the other hand, bishops Nicholas O'Flanagan (Elphin) and Francesco Coppini reported only 800 dead Yorkists.[58] Other contemporary sources gave higher numbers, ranging from 30,000 to 38,000; Hall quoted an exact figure of 36,776.[16][56] An exception was the Annales rerum anglicarum, which stated the Lancastrians had 9,000 casualties, an estimate Ross and Wolffe found to be more believable.[16][59] The Lancastrian nobility had heavy losses. The Earl of Northumberland, lords Welles, Mauley, and Dacre, and Sir Andrew Trollope fell in battle, while the earls of Devon and Wiltshire were afterwards taken and executed.[59] Lord Dacre was said to have been killed by an archer who was perched in a "bur tree" (a local term for an elder).[60] Conversely, the Yorkists lost only one notable member of the gentry—Horne—at Towton.[35]

Aftermath

On receiving news of their army's defeat, Henry fled into exile in Scotland with his wife and son. They were later joined by Somerset, Roos, Exeter, and the few Lancastrian nobles who escaped from the battlefield. The Battle of Towton severely reduced the power of the House of Lancaster in England; the linchpins of their power at court (Northumberland, Clifford, Roos, and Dacre) had either died or fled the country, ending the house's domination over the north of England.[61] Edward further exploited the situation, naming 14 Lancastrian peers as traitors.[62] Approximately 96 Lancastrians of the rank of knight and below were also attainted—24 of them members of parliament.[63]

The new king preferred winning over his enemies to his cause; the nobles he attainted either died in the battle or had refused to submit to him. The estates of a few of these nobles were confiscated by the crown but the rest were untouched, remaining in the care of their families.[62] Edward also pardoned many of those he attainted after they submitted to his rule.[64]

Although Henry was at large in Scotland with his son, the battle put an end (for the time being) to disputes over the country's state of leadership since the Act of Accord. The English people were assured that there was now one true king—Edward.[61][65] He turned his attention to consolidating his rule over the country, winning over the people and putting down the rebellions raised by the few remaining Lancastrian diehards.[66] He knighted several of his supporters and elevated several of his gentry supporters to the peerage; Fauconberg was made the Earl of Kent.[67] Warwick benefited from Edward's rule after the battle.[68] He received parts of Northumberland's and Clifford's holdings,[69] and was made "the king's lieutenant in the North and admiral of England."[70] Edward bestowed on him many offices of power and wealth, further enhancing the earl's considerable influence and riches.[71]

By 1464, the Yorkists had "wiped out all effective Lancastrian resistance in the north of England."[72] Edward's reign was not interrupted until 1470;[49] by then, his relationship with Warwick had deteriorated to such an extent that the earl defected to the Lancastrians and forced Edward to flee England, restoring Henry to the throne.[73] The interruption of Yorkist rule was brief, as Edward regained his throne after defeating Warwick and his Lancastrian cohorts at the Battle of Barnet in 1471.[74]

Literature

.jpg)

In the sixteenth century William Shakespeare wrote a number of dramatisations of historic figures. The use of history as a backdrop, against which the familiar characters act out Shakespeare's drama, lends a sense of realism to his plays.[75] Shakespeare wrote a three-part play about Henry VI, relying heavily on Hall's chronicle as a source.[76] His vision of the Battle of Towton (Henry VI, Part 3, Act 2, Scene 5), touted as the "bloodiest" engagement in the Wars of the Roses,[65][77] became a set piece about the "terror of civil war, a national terror that is essentially familial".[75] Historian Bertram Wolffe said it was thanks to Shakespeare's dramatisation of the battle that the weak and ineffectual Henry was at least remembered by English society, albeit for his pining to have been born a shepherd rather than a king.[78]

Shakespeare's version of the battle presents a notable scene that comes immediately after Henry's soliloquy. Henry witnesses the laments of two soldiers in the battle. One slays his opponent in hope of plunder, only to find the victim is his son; the other kills his enemy, who turns out to be his father. Both killers have acted out of greed and fell into a state of deep grieving after discovering their misdeeds.[79] Shakespearian scholar Arthur Percival Rossiter names the scene as the most notable of the playwright's written "rituals". The delivery of the event follows the pattern of an opera: after a long speech, the actors alternate among one another to deliver single-line asides to the audience.[80] In this scene of grief – in a reversal of the approach adopted in his later historical plays – Shakespeare uses anonymous fictional characters to illustrate the ills of civil war while a historical king reflects on their fates.[75] Michael Hattaway, Emeritus Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield, comments that Shakespeare intended to show Henry's sadness over the war, to elicit the same emotion among the audience and to expose Henry's ineptness as king.[81]

The Battle of Towton was re-examined by Geoffrey Hill in his poem "Funeral Music" (1968). Hill presents the historical event through the voices of its combatants, looking at the turmoil of the era through their eyes.[82][83] The common soldiers grouse about their physical discomforts and the sacrifices that they had made for the ideas glorified by their leaders.[84] They share their superiors' determination to seek the destruction of their opponents, even at the cost of their lives.[85] Hill depicts the participants' belief that the event was pre-destined and of utmost importance as a farce; the world went about its business regardless of the Battle of Towton.[86]

Legacy

In 1483 Richard III, younger brother of Edward IV, started to build a chapel to commemorate the battle.[87] Richard died at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 and the building was never completed. It eventually fell into disrepair and collapsed.[88] The ruins of the structure were evident five centuries later.[89] In 1929, a stone cross supposedly from the chapel was used to create the Towton Cross (also known as Lord Dacre's Cross) to commemorate those who died in the battle.[90] Several mounds on the battlefield were thought to contain casualties of the battle, although historians believe these to be tumuli of much earlier origin.[91][92] More burial sites related to the battle are found on Chapel Hill and around Saxton.[89] Lord Dacre was buried at the Church of All Saints in Saxton and his tomb was reported in the late 19th century to be well maintained, although several of its panels had been weathered away.[93] The bur tree from which Dacre's killer shot his arrow was cut down by the late 19th century,[94] leaving its stump on the battlefield. Centuries after the battle, relics that have been found in the area include rings, arrowheads and coins.[89]

The people of Elizabethan-era England remembered the battle as dramatised by Shakespeare,[95] and the image of the engagement as the charnel house where many sons of England were cut down endured for centuries.[77] However, at the start of the 21st century, the "largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil"[1] was no longer prominent in the public consciousness. British journalists lamented that people were ignorant of the Battle of Towton and of its significance.[96] According to English Heritage, the battle was of the "greatest importance"; it was one of the largest, if not the largest, fought in England and it resulted in the replacement of one royal dynasty by another.[48] Hill expressed a different opinion. Although impressed with the casualty figures touted by the chroniclers, he believed the battle brought no monumental changes to the lives of the English people.[97]

The Battle of Towton was associated with a tradition previously upheld in the village of Tysoe, Warwickshire. For several centuries a local farmer had scoured a hill figure, the Red Horse of Tysoe, each year, as part of the terms of his land tenancy. While the origins of the tradition have never been conclusively identified, it was locally claimed this was done to commemorate the Earl of Warwick's inspirational deed of slaying his horse to show his resolve to stand and fight with the common soldiers. The tradition died in 1798 when the Inclosure Acts implemented by the English government redesignated the common land, on which the equine figure was located, as private property.[98][99] The scouring was revived during the early 20th century but has since stopped.[100][101]

References

- Gravett 2003, p. 7.

- Wolffe 2001, p. 289.

- Ross 1997, pp. 11–18.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 147.

- Hicks 2002, p. 211.

- Wolffe 2001, pp. 324–327.

- Ross 1997, pp. 7, 33.

- Harriss 2005, p. 538.

- Ross 1997, pp. 29–32.

- Hicks 2002, pp. 216–217.

- Wolffe 2001, pp. 330–331.

- Ross 1997, p. 35.

- Wolffe 2001, pp. 332–333.

- Hicks 2002, pp. 218–219.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 32–39.

- Ross 1997, p. 37.

- Gravett 2003, p. 47.

- Morgan 2000, pp. 38, 40.

- Gravett 2003, p. 44.

- Gravett 2003, p. 25.

- Ross 1997, p. 36.

- Wolffe 2001, p. 331.

- Scott 2010, p. 24.

- Goodman 1990, p. 51.

- Jones 2012.

- Penn 2019, p. 46.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 126,156.

- Goodman 1990, p. 165.

- Hicks 2002, pp. 147, 240.

- Hicks 2002, p. 179.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 20–21.

- Goodman 1990, p. 166.

- Ross 1997, p. 17.

- Gravett 2003, p. 20.

- Ross 1997, p. 38.

- English Heritage 1995, pp. 2–5.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 50–51.

- English Heritage 1995, p. 2.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 44–46.

- Halsall 2000, p. 41.

- Gravett 2003, p. 46.

- Halsall 2000, p. 42.

- Gravett 2003, p. 59.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 52–53.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 53–56.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 56–57.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 60–61, 65.

- English Heritage 1995, p. 6.

- Harriss 2005, p. 644.

- Gravett 2003, p. 68.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 50, 69–73.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 85–89.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 37, 88.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 72–73.

- Gravett 2003, p. 73.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 79–80.

- Hinds 1912, pp. 68, 73.

- Hinds 1912, pp. 65, 81.

- Wolffe 2001, p. 332.

- Gravett 2003, p. 77.

- Ross 1997, pp. 37–38.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 159.

- Ross 1997, p. 67.

- Ross 1997, pp. 67–68.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 149.

- Ross 1997, pp. 41–63.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 148.

- Ross 1997, p. 70.

- Carpenter 2002, p. 158.

- Hicks 2002, p. 221.

- Ross 1997, pp. 70–71.

- Wolffe 2001, pp. 335–337.

- Hicks 2002, pp. 281, 292, 296.

- Ross 1997, p. 171.

- Berlin 2000, p. 139.

- Edelman 1992, p. 39.

- Saccio 2000, p. 141.

- Wolffe 2001, p. 3.

- Warren 2003, p. 236.

- Hattaway & Shakespeare 1993, pp. 32–34.

- Hattaway & Shakespeare 1993, p. 34.

- Sherry 1987, pp. 86–87.

- Wainwright 2005, p. 7.

- Sherry 1987, pp. 88.

- Wainwright 2005, p. 18.

- Wainwright 2005, pp. 19, 37.

- Markham 1906, p. 37.

- Brooke 1857, p. 100.

- English Heritage 1995, p. 1.

- Gravett 2003, p. 51.

- Gravett 2003, p. 86.

- Fiorato 2007, p. 5.

- Fallow 1889, pp. 303–305.

- Ransome 1889, p. 463.

- Styles 2002, p. 107.

- Gill 2008; Hardman 2009; Kettle 2007

- Wainwright 2005, p. 83.

- Harris 1935.

- Salzman 1949, p. 175.

- Askew 1935.

- Gibson 1936, p. 180.

Bibliography

Books

- Berlin, Normand (2000) [1993]. O'Neill's Shakespeare. Michigan, United States: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.14276. ISBN 978-0-472-10469-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brooke, Richard (1857). "The Field of the Battle of Towton". Visits to Fields of Battle in England. London, United Kingdom: John Russell Smith. pp. 81–129.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carpenter, Christine (2002) [1997]. The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the constitution in England, c. 1437–1509. New York, United States: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31874-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edelman, Charles (1992). "The Wars of the Roses: 2 and 3 Henry VI, Richard III". Brawl Ridiculous: Swordfighting in Shakespeare's Plays. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. pp. 69–89. ISBN 978-0-7190-3507-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodman, Anthony (19 July 1990) [1981]. "Local Revolts and Nobles' Struggles, 1469–71". The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–97. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 66–85. ISBN 978-0-415-05264-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gravett, Christopher (2003). Towton 1461: England's Bloodiest Battle (PDF). Campaign. 120. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing (published 20 April 2003). ISBN 978-1-84176-513-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harriss, G.L. (2005). Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461. New Oxford History of England. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press (published 27 January 2005). ISBN 978-0-19-822816-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hattaway, Michael & Shakespeare, William (1993). "The Play: 'What Should be the Meaning of All Those Foughten Fields?'". The Third Part of King Henry VI. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–35. ISBN 0-521-37705-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hicks, Michael (2002) [1998]. Warwick the Kingmaker. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23593-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markham, Clements (1906). "The Crowning Victory of Towton". Richard III: His Life and Character. London, United Kingdom: Smith, Elder & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Penn, Thomas (2019). The Brothers York. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1846146909.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Charles (1997) [1974]. Edward IV. English Monarchs series (revised ed.). Connecticut, United States: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07372-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saccio, Peter (2000) [1977]. Shakespeare's English Kings: History, Chronicle, and Drama. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512319-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salzman, Louis Francis, ed. (1949). "Parishes—Tysoe". A History of the County of Warwick. 5. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–182.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherry, Vincent B. (1987). "King Log: Thorny Craft". The Uncommon Tongue: The Poetry and Criticism of Geoffrey Hill. Michigan, United States: University of Michigan Press. pp. 81–125. ISBN 0-472-10084-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wainwright, Jeffrey (2005). Acceptable Words: Essays on the Poetry of Geoffrey Hill. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6754-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolffe, Bertram (2001) [1981]. Henry VI. English Monarchs series (Yale ed.). New Haven, CT, US: Yale University Press (published 10 June 2001). ISBN 978-0-300-08926-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Essays and journals

- Askew, H. (1 June 1935). "The Tysoe Red Horse" (PDF, subscription required). Notes and Queries. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 168: 394. doi:10.1093/nq/CLXVIII.jun01.394e. ISSN 1471-6941. Retrieved 15 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fallow, Thomas McCall (January 1889). "The Dacre Tomb in Saxton Churchyard". The Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Journal. London, United Kingdom: Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association. 10: 303–308. Retrieved 14 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiorato, Veronica (2007). "The Context of the Discovery". Blood Red Roses: The Archaeology of a Mass Grave from the Battle of Towton AD 1461 (Second revised ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxbow. ISBN 1-84217-289-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibson, Strickland (1936). "Francis Wise, B. D" (PDF). Notes and Queries. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. 1: 173–195. ISSN 0308-5562. Retrieved 17 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halsall, Trevor James (2000). "Geological Constraints on Battlefield Tactics: Examples in Britain from the Middle Ages to the Civil Wars". In Rose, Edward P. F.; Nathanail, C. Paul (eds.). Geology and Warfare: Examples of the Influence of Terrain and Geologists on Military Operations. Bath, United Kingdom: Geological Society of London. pp. 32–59. ISBN 1-86239-065-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Mary Dormer (18 May 1935). "The Tysoe Red Horse" (PDF). Notes and Queries. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 168: 349. doi:10.1093/nq/CLXVIII.may18.349a. ISSN 1471-6941. Retrieved 15 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hinds, Allen B., ed. (1912). Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts in the Archives and Collections of Milan 1385–1618. London: Stationery Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Philip (2000). "The Naming of Battlefields in the Middle Ages". In Dunn, Diana (ed.). War and Society in Medieval and Early Modern. Liverpool, United Kingdom: Liverpool University Press. pp. 34–52. ISBN 0-85323-885-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ransome, Cyril (July 1889). "The Battle of Towton". The English Historical Review. 4: 460–466. doi:10.1093/ehr/IV.XV.460. Retrieved 11 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, Douglas Dowell (2010). "Military Medicine in the Pre-Modern Era: Using Forensic Techniques in the Archaeological Investigation of Military Remains". The Historical Archaeology of Military Sites: Method and Topic. Texas, United States: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 21–29. ISBN 978-1-60344-207-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Styles, Philip (2002) [1964]. "The Commonwealth". In Nicoll, John Ramsay Allardyce (ed.). Shakespeare Survey. Shakespeare Criticism. 17. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–119. ISBN 0-521-52353-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutherland, Tim (2009). "Killing Time: Challenging the Common Perceptions of Three Medieval Conflicts—Ferrybridge, Dintingdale and Towton—'The Largest Battle on British Soil'" (PDF). Journal of Conflict Archaeology. 5 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1163/157407709x12634580640173. ISSN 1574-0773. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warren, Roger (2003) [1984]. "An Aspect of Dramatic Technique in Henry VI". In Alexander, Catherine M. S. (ed.). Shakespeare Criticism. The Cambridge Shakespeare Library. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82433-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Newspaper articles

- Gill, A.A. (24 August 2008). "Towton, the Bloodbath that Changed the Course of Our History". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hardman, Robert (10 April 2009). "Battles of Britain: They are the Sites of Bloody Clashes that Shaped This Nation, Now You can Fight to Save Them". Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Nigel (29 March 2012). "Towton was our worst ever battle, so why have we forgotten this bloodbath in the snow?". Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kettle, Martin (25 August 2007). "Our Most Brutal Battle has been Erased from Memory". The Guardian. p. 33. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online sources

- "English Heritage Battlefield Report: Towton 1461" (PDF). English Heritage. 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

Further reading

- Goodwin, George (2011). "The Battle of Towton". History Today. Vol. 61 no. 5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadler, John (2011). Towton: The Battle of Palm Sunday Field 1461. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-965-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)