Edward IV of England

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470,[1] and again from 11 April 1471 until his death.

| Edward IV | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of England (more...) | |

| 1st Reign | 4 March 1461 – 3 October 1470 |

| Coronation | 28 June 1461 |

| Predecessor | Henry VI |

| Successor | Henry VI |

| 2nd Reign | 11 April 1471 – 9 April 1483 |

| Predecessor | Henry VI |

| Successor | Edward V |

| Born | 28 April 1442 Rouen, Normandy, France |

| Died | 9 April 1483 (aged 40) Westminster, Middlesex, England |

| Burial | 18 April 1483 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others |

|

| House | York |

| Father | Richard, Duke of York |

| Mother | Cecily Neville |

| Signature |  |

| English Royalty |

| House of York |

|---|

His father, Richard of York, leader of the Yorkist faction, was a lineal descendant of Edward III and until 1453, heir presumptive to Henry VI, from the ruling Lancastrians. Less than a year old when he came to the throne in September 1422, Henry's minority was marked by political infighting within the Regency council. After 1437, he ruled in his own right but his weak and indecisive personality did little to mitigate factional conflict.

Shortly after the birth of his son Edward of Westminster in 1453, Henry suffered a complete mental breakdown and the government descended into chaos. Conflict between Yorkists and Lancastrians led to civil war in 1455. This continued intermittently until 1485 and is collectively known as The Wars of the Roses. After Richard was executed in December 1460, Edward became head of the family; with the support of the Earl of Warwick, or 'The Kingmaker', he deposed Henry and was crowned king in June 1461.

Divisions developed after Edward's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville in 1464; Warwick switched sides in 1470 and restored Henry to the throne. Edward fled to Flanders, but returned to England in March 1471, winning victories at Barnet in April and Tewkesbury in May. Warwick, Henry's heir Edward of Westminster and other senior Lancastrians were killed, while Henry died in the Tower of London a few days later.

England remained relatively peaceful until Edward's death in 1483. His two minor sons, Edward and Richard were subsequently declared illegitimate by his younger brother, the Duke of Gloucester, who became Richard III.

Early life

Edward, Earl of March, was born at Rouen in Normandy, eldest surviving son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, and Cecily Neville. His father, commonly referred to as 'York', was a lineal descendant of Edward III and heir to Henry VI, until the birth of Henry's son Edward of Westminster in 1453.[lower-alpha 1][2]

Less than a year old when he came to the throne in September 1422, Henry's reign was marked by periods of mental illness, economic decline and military defeat; by 1453, only Calais remained of the once extensive English possessions in France. This created a power vacuum, in which two major factions struggled for control; 'Yorkist', headed by York and his Neville allies, Salisbury and his son, Warwick. The other, or Lancastrian, was led by Henry's wife, Margaret of Anjou and the Beauforts, principally Edmund, Duke of Somerset, then his eldest son Henry after his death at St Albans in 1455.[3]

York was appointed Lord Protector and an uneasy peace continued until 1459, when Margaret felt strong enough to challenge him. He fled England with the Nevilles and his two eldest sons, Edward and Edmund; in July 1460, they returned and captured Henry at Northampton.[4] Many who had supported York's demand for changes in Henry's government, withdrew when he claimed the throne himself, leading to Lancastrian risings in Wales and Yorkshire. Warwick remained in London, while Edward went to Wales; the others marched north, and were defeated at Wakefield on 30 December. York and Edmund were killed in the pursuit, Salisbury executed the next day and their heads displayed on Micklegate Bar.[5]

Reign

Accession to the throne

His father's death made Edward leader of the Yorkist faction; at this stage of his career, contemporaries like Philippe de Commines described him as handsome and affable, as well as being full of energy.[6] His physique and height of approximately 6 feet 4 inches (193 centimeters) made him an impressive sight in armour, while he took care to wear splendid clothes. This was in contrast to his father, who was small and dark, or Henry, whose physical and mental frailties undermined his cause.[7]

On 2–3 February 1461, Edward won a hard-fought victory at Mortimer's Cross, a battle preceded by a meteorological phenomenon known as parhelion, or three suns, which he took as his emblem, the "Sun in splendour.[8] However, on 17 February Warwick was defeated at the Second Battle of St Albans, allowing the Lancastrians to regain custody of Henry VI. The two men met in London, where Edward was hastily crowned king, before leading his army north. The Battle of Towton took place on 29 March; reputedly the bloodiest battle ever on English soil, it ended in a decisive Yorkist victory. Estimates of the dead range from 9,000 to 20,000; in 1996, a mass grave containing 46 skeletons was uncovered and an analysis of their injuries shows the brutality of the contest.[9]

Margaret fled abroad with her son and other leading Lancastrians, while Edward returned to London for a formal coronation.[10] A series of Lancastrian risings ended with John Neville's victory in the 1464 Battle of Hexham.[11] Henry VI escaped into the Pennines; [12] after a year spent in hiding, he was finally caught and imprisoned in the Tower of London. There was little point in killing him while his son remained alive, since this would merely have transferred the Lancastrian claim from a captive king to one who was at liberty.[13]

1461 to 1470

Since most of the nobility either remained loyal to Henry VI or stayed neutral, the new regime relied heavily on the Nevilles, whose support was crucial in putting Edward on the throne. However, divisions soon developed, largely due to the perception Edward was controlled by Warwick, who did little to deny it. The need to establish order and put down Lancastrian conspiracies initially concealed their growing estrangement but it burst into the open in 1464.[14]

Although Edward preferred Burgundy as an ally, he allowed Warwick to negotiate a treaty with Louis XI of France; it included a suggested marriage between Edward, and Louis's daughter Anne, or sister-in-law Bona of Savoy.[15] In October 1464, Warwick was enraged to discover that on 1 May, Edward had secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, a widow with two sons, whose Lancastrian husband, John Grey of Groby, died at Towton.[16] If nothing else, it was a clear demonstration he was not in control of Edward, despite suggestions to the contrary.[17]

Edward's motives have been widely discussed by contemporaries and historians alike. Elizabeth's mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, came from the upper nobility, but her father, Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers, was a middle ranking provincial knight. His Privy Council told Edward with unusual frankness, "she was no wife for a prince such as himself, for she was not the daughter of a duke or earl."[18] The marriage was both unwise and unusual, although not unknown; Henry VI's mother, Catherine of Valois, married her chamberlain, Owen Tudor, while Edward's direct descendant, Henry VIII, created a new church to marry Anne Boleyn. By all accounts, Elizabeth possessed considerable charm of person and intellect, while Edward was used to getting what he wanted.[19]

Historians generally accept it was an impulsive decision, but differ on whether it was also a "calculated political move". One view is the low status of the Woodvilles was part of the attraction, since unlike the Nevilles, they were reliant on Edward and thus more likely to remain loyal.[20] Others argue if this was his purpose, there were far better options available; all agree it had significant political implications, that impacted the rest of Edward's reign.[21]

Unusually for the period, 12 of the Earl's 14 children survived into adulthood, creating a large pool of competitors for offices and estates, as well as in the matrimony market. Elizabeth's sisters made a series of advantageous unions, including that of Catherine Woodville to Henry Stafford, later Duke of Buckingham, Anne Woodville to William, heir to the Earl of Essex, and Eleanor Woodville with Anthony Grey, heir to the Earl of Kent.[22]

In 1467, Edward dismissed his Lord Chancellor, Warwick's brother George Neville, Archbishop of York. Warwick responded by building an alliance with Edward's disaffected younger brother and current heir, George, Duke of Clarence, who held estates adjacent to the Neville heartland in the north. Concerned by this, Edward blocked a proposed marriage between Clarence and Warwick's eldest daughter Isabel.[23]

In early July, Clarence traveled to Calais, where he married Isabel in a ceremony conducted by George Neville and overseen by Warwick. The three men issued a 'remonstrance', listing alleged abuses by the Woodvilles and other advisors close to Edward. They returned to London, where they assembled an army to remove these 'evil councillors' and establish good government.[24]

With Edward still in the north, the Royal Army was defeated by a Neville force at Edgecote Moor on 26 July 1469. After the battle, Edward was held in Middleham Castle; on 12 August, Earl Rivers and his younger son John Woodville were executed at Kenilworth. However, it soon became clear there was little support for Warwick or Clarence; Edward was released in September and resumed the throne.[25]

Outwardly, the situation remained unchanged but tensions persisted and Edward did nothing to reduce the Nevilles' sense of vulnerability. The Percys, traditional rivals of the Neville family in the North, fought for Lancaster at Towton; their titles and estates were confiscated and given to Warwick's brother John Neville. In early 1470, Edward reinstated Henry Percy as Earl of Northumberland; John was compensated with the title Marquess of Montagu, but this was a significant demotion for a key supporter.[26]

In March 1470, Warwick and Clarence exploited a private feud to initiate a full-scale revolt; when it was defeated, the two fled to France in May 1470.[27] Seeing an opportunity, Louis persuaded Warwick to negotiate with his long-time enemy, Margaret of Anjou; she eventually agreed, first making him kneel before her in silence for fifteen minutes.[28] With French support, Warwick landed in England on 9 September 1470 and announced his intention to restore Henry.[29] By now, the Yorkist regime was deeply unpopular and the Lancastrians rapidly assembled an army of over 30,000; when John Neville switched sides, Edward was forced into exile.[30]

Restoration

Edward took refuge in Flanders, part of the Duchy of Burgundy, accompanied by a few hundred men, including his younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Anthony Woodville and William Hastings.[31] The Duchy was ruled by Charles the Bold, husband of his sister Margaret; he provided minimal help, something Edward never forgot.[32]

The restored Lancastrian regime faced the same issue that dominated Henry's previous reign. Mental and physical frailties made him incapable of ruling and resulted in an internal struggle for control, made worse because the coalition that put him back on the throne consisted of bitter enemies. Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, held Warwick responsible for his fathers death in 1455, while he had executed his elder brother in 1464; Warwick and Clarence quickly found themselves isolated by the new regime.[33]

Backed by wealthy Flemish merchants, in March 1471 Edward landed near Hull, close to his estates in Yorkshire. Supporters were initially reluctant to commit; the key northern city of York opened its gates only when he claimed to be seeking the return of his dukedom, like Henry IV seventy years earlier. The first significant contingent to join was a group of 600 men under William Parr and Sir James Harrington.[34] Parr fought against the Yorkists at Edgecote in 1469 and his defection confirmed Clarence's decision to switch sides; as they marched south, more recruits came in, including 3,000 at Leicester.[35]

Edward entered London unopposed and took Henry prisoner; Warwick was defeated and killed at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April, while a second Lancastrian army was destroyed at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May. 16 year old Edward of Westminster died on the battlefield, with surviving leaders like Somerset executed shortly afterwards. This was followed by Henry's death a few days later; a contemporary chronicle claimed this was due to "melancholy," but it is generally assumed he was killed on Edward's orders.[36]

Although the Lancastrian cause seemed at an end, the regime was destabilised by an ongoing quarrel between Clarence and his brother Gloucester. The two were married to Isabel Neville and Anne Neville respectively, Warwick's daughters by Anne Beauchamp and heirs to their mother's considerable inheritance.[37] Many of the estates held by the brothers had been granted by Edward, who could also remove them, making them dependent on his favour. This was not the case with property acquired through marriage and explains the importance of this dispute.[38]

Later reign and death

The last significant rebellion ended in March 1474 with the surrender of the Earl of Oxford, who survived to command the Lancastrian army at Bosworth in 1485. Clarence was widely suspected of involvement, one of the factors that eventually led to his imprisonment and private execution in the Tower of London on 18 February 1478. Tradition claims he "drowned in a butt of Malmsey wine", which appears to have been a joke by Edward, referring to Clarence's favourite drink.[39]

In 1475, Edward allied with Burgundy, and declared war on France. However, with Duke Charles focused on besieging Neuss, Louis opened negotiations and soon after Edward landed at Calais, the two signed the Treaty of Picquigny.[40] Edward received an immediate payment of 75,000 crowns, plus a yearly pension of 50,000 crowns, thus allowing him to "recoup his finances."[41]

In 1482, he backed an attempt to usurp the Scottish throne by Alexander Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany, brother of James III of Scotland. Gloucester invaded Scotland and took the town of Edinburgh, but not the far more formidable castle, where James was being held by his own nobles. Albany switched sides and without siege equipment, the English army was forced to withdraw, with little to show for an expensive campaign, apart from the capture of Berwick Castle.[42]

Edward's health began to fail, and he became subject to an increasing number of ailments; his physicians attributed this in part to a habitual use of emetics, which allowed him to gorge himself at meals, then return after vomiting to start again.[43] He fell fatally ill at Easter 1483, but survived long enough to add some codicils to his will, the most important naming his brother as Protector after his death. He died on 9 April 1483 and was buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. His twelve-year-old son, Edward V of England, was never crowned, Gloucester becoming Richard III in July.[44]

The cause of Edward's death is uncertain; allegations of poison were common in an era when lack of medical knowledge meant death often had no obvious explanation. Other suggestions include pneumonia or malaria, although both were well-known and easy to describe. One contemporary attributed it to apoplexy brought on by excess, which fits with our knowledge of his physical habits.[45]

Overview

While the War of the Roses has been documented by numerous historians, Edward himself is less well known; 19th century historians like William Stubbs generally dismissed him as a bloodthirsty nonentity. The most comprehensive modern biography was written by Charles Ross in 1974, who concluded despite Edward's abilities, his reign was ultimately a failure. Ross states Edward ’remains the only king in English history since 1066 in active possession of his throne who failed to secure the safe succession of his son. His lack of political foresight is largely to blame for the unhappy aftermath of his early death.’[46]

Economic & Military

In his youth, Edward was a capable and charismatic military commander, who led from the front but as he grew older, the energy noted by contemporaries dissipated.[47] He showed little desire to campaign on his own behalf; in 1475, 1477 and 1482, Parliament was asked to approve taxes for wars which he failed to prosecute. Commentators observe a marked difference between his first period as king, and the second; his attempts to reconcile former enemies like Somerset and Clarence failed, and after 1471, Edward became noticeably more ruthless.[48]

Although the economy recovered from the depression of 1450 to 1470, Edward's spending habitually exceeded the income from taxes; on his death in 1483, the Crown had less than £1,200 in cash. His close relationship with the London branch of the Medici Bank ended in its bankruptcy; in 1517, the Medicis were still seeking repayment of Edward's debts.[49] He invested heavily in joint ventures within the City of London, which he also used as a source of funding.[50]

Under his rule, ownership of the Duchy of Lancaster was transferred to the Crown, where it remains today. In 1478, his staff prepared the Black Book, a comprehensive review of finances still in use a century later. Documents of the Exchequer show him sending letters threatening officials if they did not pay money. His properties earned large amounts of money for the crown.

Cultural

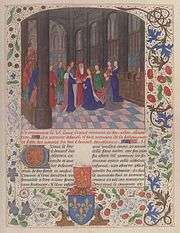

.jpg)

Edward's court was described by a visitor from Europe as "the most splendid ... in all Christendom".[51] He spent large amounts on expensive status symbols to show off his power and wealth as king of England, while his collecting habits show an eye for style and an interest in scholarship, particularly history. He acquired fine clothes, jewels, and furnishings, as well as a collection of beautifully illuminated historical and literary manuscripts, many made specially for him by craftsmen in Bruges.[52] [53]

These included books for both entertainment and instruction, whose contents reveal his interests. They focus on the lives of great rulers, including Julius Caesar,[54] historical chronicles,[55] and instructional and religious works.[56] In 1476, William Caxton established the first English printing press in the outbuildings of Westminster Abbey; on 18 November 1477, he produced Sayengis of the Philosophres, translated into English for Edward by Anthony Woodville.[57]

It is not known where or how Edward's library was stored, but it is recorded that he transferred volumes from the Great Wardrobe to Eltham Palace and that he had a yeoman "to kepe the king's bookes".[58] [59] More than forty of his books survive intact from the 15th century, which suggests they were carefully stored together.[60] Today they form the foundation of the Royal Collection of manuscripts at the British Library.

Edward spent large sums on Eltham Palace, including the still-extant Great Hall, site of a feast for 2,000 people in December 1482, shortly before his death in April.[61] He also began a major upgrade of St George's Chapel, Windsor, where he was buried in 1483.

Successors

His eldest son Edward was dubbed Prince of Wales when he was seven months old and at the age of three, given his own household. He was based in Ludlow Castle, as nominal head of the Council of Wales and the Marches; his uncle, Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, supervised his upbringing and carried out the duties associated with Presidency of the Council.[62]

Prior to his succession, Richard III declared Edward and Richard illegitimate, on the grounds his brother's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid.[63] The Titulus Regius argued Edward had agreed to marry Lady Eleanor Talbot, rendering his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville void. Both parties were dead, but a clergyman, named as Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, claimed to have carried out the ceremony. This was later reversed by Henry VII; Stillington died in prison in 1491.[64]

The historical consensus is Edward and Richard were killed at some point, probably between July to September 1483; debate on who gave the orders, and why, continues.[65] By mid-August, Elizabeth Woodville was certain of their death; after her initial grief turned to fury, she opened secret talks with Margaret Beaufort. She promised her support, in return for Henry's agreement to marry her eldest daughter Elizabeth of York.[63] In December 1483, Henry swore an oath to do so, which he carried out after his coronation in October 1485.[66]

Edward's Legitimacy

Both Warwick and Clarence made accusations about Edward's paternity to further their own political aims. Dominic Mancini reported Cecily Neville threatened to declare her son a bastard when she discovered his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. However, this claim was not repeated by any other contemporaries.[67]

Historians generally view this as propaganda designed to discredit Edward and his heirs; he, Clarence and their sister Margaret were physically very similar, all three being tall and blonde, while their father was short and dark.[68] When Richard declared his nephew Edward V illegitimate, he did so on the grounds his brother's marriage was invalid.[63]

In 2004, a television documentary suggested Edward may not have been the son of Richard of York, a claim based on circumstantial evidence that has since been challenged.[69]

Marriage and children

.svg.png)

Edward had ten children by Elizabeth Woodville, seven of whom survived him; they were declared illegitimate under the 1483 Titulus Regius, an act repealed by Henry VII, who married his eldest daughter, Elizabeth.[70]

- Elizabeth of York, queen consort of Henry VII, (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503).

- Mary of York (11 August 1467 – 23 May 1482).

- Cecily of York (20 March 1469 – 24 August 1507); married John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles, then Thomas Kyme or Keme;

- Edward V, (4 November 1470 – c. 1483); disappeared, assumed murdered prior to his coronation, ca 1483;

- Margaret of York (10 April 1472 – 11 December 1472).

- Richard, Duke of York, (17 August 1473 – c. 1483); disappeared, assumed murdered ca 1483;

- Anne of York (2 November 1475 – 23 November 1511); married Thomas Howard (later 3rd Duke of Norfolk).

- George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Bedford (March 1477 – March 1479).

- Catherine of York (14 August 1479 – 15 November 1527); married William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon.

- Bridget of York (10 November 1480 – 1517); became a nun.

Edward had numerous mistresses, including Lady Eleanor Talbot and Elizabeth Lucy, possibly daughter of Thomas Waite (or Wayte), of Southampton. The most famous was Jane Shore, later compelled by Richard to perform public penance at Paul's Cross; Sir Thomas More claimed this backfired, since albeit she were out of al array save her kyrtle only: yet went she so fair & lovely … that her great shame wan her much praise.[71]

He had several acknowledged illegitimate children;

- Elizabeth Plantagenet (born circa 1464), possibly daughter of Elizabeth Lucy, who married Thomas, son of George Lumley, Baron Lumley[72][73] [74]

- Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (1460s/1470s – 3 March 1542), author of the Lisle Papers, an important historical source for the Tudor period. From his first marriage to Elizabeth Grey, he had three daughters, Frances, Elizabeth and Bridget Plantagenet.

- Grace Plantagenet, recorded as attending the funeral of Elizabeth Woodville in 1492;[75]

There are claims for many others, including Mary, second wife of Henry Harman of Ellam, and Isabel Mylbery (born circa 1470), who married John Tuchet, son of John Tuchet, 6th Baron Audley. However, the evidence for these is circumstantial.[76]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Edward IV of England[77] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- "Edward IV". Archontology.org. 14 March 2010.

Set sail on 2 October 1470 from England and took refuge in Burgundy; deposed as King of England on 3 October 1470

- Ross 1974, pp. 3–7.

- Penn 2019, p. 5.

- Ross 1974, p. 32.

- Ross 1974, p. 30.

- Kleiman 2013, p. 83.

- Seward 1997, p. 97.

- Penn 2019, p. 4.

- Gravett 2003, pp. 85-89.

- Penn 2019, pp. 54-55.

- Ross 1974, p. 61.

- "Muncaster – Monument to Henry VI". Visit Cumbria. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Ross 1974, p. 62.

- Penn 2019, p. 60.

- Ross 1974, p. 91.

- Ross 1974, pp. 85–86.

- Penn 2019, p. 114.

- Ross 1974, p. 85.

- Penn 2019, pp. 112-113.

- Wilkinson 1964, p. 146.

- Carpenter 1997, p. 170.

- Ross 1974, p. 93.

- Penn 2019, pp. 203-205.

- Penn 2019, pp. 210-211.

- Gillingham 1982, p. 160.

- Ross 1974, pp. 135–136.

- Kendall 1970, p. 228.

- Ashley 1961, p. 170.

- Kendall 1970, p. 236.

- Ross 1974, pp. 152–153.

- Penn 2019, p. 243.

- Penn 2019, pp. 256-258.

- Penn 2019, pp. 260-261.

- Horrox 1989, p. 41.

- Penn 2019, p. 263.

- Wolfe 1981, p. 347.

- Ross 1981, pp. 26-27.

- Penn 2019, pp. 306-307.

- Penn 2019, p. 406.

- Penn 2019, pp. 364-365.

- Hicks 2011, p. 18.

- Penn 2019, pp. 434-435.

- Penn 2019, p. 431.

- Penn 2019, p. 494.

- Ross 1992, pp. 414-415.

- Ross 1974, p. 451.

- Penn 2019, p. 370.

- Whittle 2017, pp. 22-24.

- Rorke 2006, p. 270.

- Ross 1974, p. 351.

- Ross (1974), pp. 270–277.

- Backhouse 1987, pp. 26, 28, 39.

- McKendrick 2011, pp. 42–65.

- "La Grande histoire César". Digitised Manuscripts. British Library. 1479.

- "Jean de Wavrin, Recueil des croniques d'Engleterre, vol. 1". Digitised Manuscripts. British Library. 1471.

- "Guyart des Moulins, La Bible historiale". Digitised Manuscripts. British Library. 1470.

- Timbs 1855, p. 4.

- Thurley 1993, p. 141.

- Harris 1830, p. 125.

- Doyle 2011, p. 69.

- "Eltham Palace and Gardens". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Parry 1851, p. 11.

- Penn 2019, pp. 504-505.

- Crawford 2008, p. 130.

- Penn 2019, p. 497.

- Williams 1973, p. 25.

- Crawford 2008, p. 64.

- Crawford 2008, pp. 173–178.

- Wilson, Trish. "Was Edward IV Illegitimate?: The case for the defence". History Files. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Carson 2009.

- Horrox, 2004 & Oxford DNB Online.

- Corbet 2015, p. 316.

- Burke 1836, p. 290.

- Mackenzie 1825, p. 136.

- Given-Wilson 1984, pp. 158, 161–174.

- Ashdown-Hill, 2016 & Chapter 28.

- Watson 1896, p. 181.

Notes

- Henry was a descendant of John of Gaunt, Edward III's third surviving son; his grandfather, Henry of Lancaster, displaced Richard II, from the senior line. York's claim derived from the fourth son, Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, but his mother Anne de Mortimer, was the senior descendant of his second son, Lionel of Antwerp. By modern standards, this made York superior; although this was less clear at the time, Richard, and later Edward, had a legitimate claim to the throne.

Sources

- Ashdown-Hill, John (2016). The Private Life of Edward IV. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445652450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ashley, Mike (2002). British Kings & Queens. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1104-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Backhouse, Janet (1987). "Founders of the Royal Library: Edward IV and Henry VII as Collectors of Illuminated Manuscripts". In Williams, David (ed.). England in the Fifteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1986 Harlaxton Symposium. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-475-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burke, John (1836). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland Enjoying Territorial Possessions Or High Official Rank: But Uninvested with Heritable Honours, Volume II. Henry Colburn.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carpenter, Christine (1997). The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, C.1437–1509. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31874-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carson, Annette (2009). Richard III: The Maligned King. History Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7524-5208-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cokayne, G.E. (2000). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. Alan Sutton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Corbet, Anthony, Dr (2015). Edward IV, England's Forgotten Warrior King: His Life, His People, and His Legacy. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4917-4635-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crawford, Anne (2008). The Yorkists: The History of a Dynasty. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84725-197-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doyle, Kathleen (2011). McKendrick, Scot; Lowden, John; Doyle, Kathleen (eds.). The Old Royal Library. Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination. British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-5816-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillingham, John (1982). The Wars of the Roses (1990 ed.). Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297820161.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Given-Wilson, Chris; Curteis, Alice (1984). The Royal Bastards of Medieval England. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7102-0025-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gravett, Christopher (2003). Towton 1461: England's Bloodiest Battle. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-513-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hankinson (ed), C.F.J. (1949). DeBretts Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, 147th year. London: Odhams Press.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Nicholas (1830). Privy Purse expenses of Elizabeth of York: Wardrobe Accounts of Edward IV. London: William Pickering.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hicks, Michael (2011). Richard III. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7326-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horrox, Rosemary (1989). Richard III: A Study of Service. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40726-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horrox, Rosemary (2004). Shore [née Lambert], Elizabeth [Jane] (Online ed.). Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25451.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleiman, Irit Ruth (2013). Philippe de Commynes: Memory, Betrayal, Text. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-6324-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1970). Louis XI, the Universal Spider. W. W. Norton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackenzie, Eneas (1825). An Historical, Topographical, and Descriptive View of the County of Northumberland... Mackenzie and Dent.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKendrick, Scot (2011). McKendrick, Scot; Lowden, John; Doyle, Kathleen (eds.). A European Heritage, Books of Continental Origin. Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination. British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-5816-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mount, Toni (2014). Everyday Life in Medieval London: From the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-1564-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, Volume III (107th ed.). Burke's Peerage.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parry, Edward (1851). Royal visits and progresses to Wales, and the border counties.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Penn, Thomas (2019). The Brothers York. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1846146909.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rorke, Martin (2006). "English and Scottish Overseas Trade, 1300-1600". The Economic History Review. 59 (2): 265–288. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2006.00346.x. JSTOR 3805936.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Charles (1974). Edward IV. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520027817.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Charles (1981). Richard III. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 978-0413295309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seward, Desmond (1997). Wars of the Roses. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-477300-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seward, Desmond (2014). Richard III: England's Black Legend. Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-60598-603-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thurley, Simon (1993). The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: A Social and Architectural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3000-5420-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weir, Alison (1999). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. London: The Bodley Head.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whittle, Andrew (2017). The Historical Reputation of Edward IV 1461-1725 (PDF). University of East Anglia, School of History PHD.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Bertie (1964). Constitutional History of England in the Fifteenth Century (1399–1485): With Illustrative Documents. Longmans.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Neville (1973). The Life and Times of Henry VII. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-76517-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolfe, Bertram (1981). Henry VI (The English Monarchs Series). Methuen Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0413320803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Wilson, Trish. "Was Edward IV Illegitimate?: The case for the defence". History Files. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Eltham Palace and Gardens". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Edward IV at BBC History

- Portraits of King Edward IV at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts (SEARCH: Keyword Edward IV, Start year 1470, End year 1480 for details and images of Edward IV's manuscripts).

Edward IV of England House of York Cadet branch of the House of Plantagenet Born: 28 April 1442 Died: 9 April 1483 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry VI |

King of England Lord of Ireland 1461–1470 |

Succeeded by Henry VI |

| King of England Lord of Ireland 1471–1483 |

Succeeded by Edward V | |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by Richard Plantagenet |

Duke of York Earl of Cambridge Earl of March 1460–1461 |

Merged in Crown |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by Richard Plantagenet |

Earl of Ulster 1460–1461 |

Merged in Crown |