Stromatolite

Stromatolites (/stroʊˈmætəlaɪts, strə-/[1][2]) or stromatoliths (from Greek στρῶμα strōma "layer, stratum" (GEN στρώματος strōmatos), and λίθος lithos "rock")[3] are layered mounds, columns, and sheet-like sedimentary rocks that were originally formed by the growth of layer upon layer of cyanobacteria, a single-celled photosynthesizing microbe.[4][5] Fossilized stromatolites provide records of ancient life on Earth. Lichen stromatolites are a proposed mechanism of formation of some kinds of layered rock structure that are formed above water, where rock meets air, by repeated colonization of the rock by endolithic lichens.[6][7]

Morphology

Stromatolites are layered bio-chemical accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms (microbial mats) of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria.[8] They exhibit a variety of forms and structures, or morphologies, including conical, stratiform, branching, domal,[9] and columnar types. Stromatolites occur widely in the fossil record of the Precambrian, but are rare today. Very few ancient stromatolites contain fossilized microbes. While features of some stromatolites are suggestive of biological activity, others possess features that are more consistent with abiotic (non-biological) precipitation.[10] Finding reliable ways to distinguish between biologically formed and abiotic stromatolites is an active area of research in geology.[11]

Formation

Time lapse photography of modern microbial mat formation in a laboratory setting gives some revealing clues to the behavior of cyanobacteria in stromatolites. Biddanda et al. (2015) found that cyanobacteria exposed to localized beams of light moved towards the light, or expressed phototaxis, and increased their photosynthetic yield, which is necessary for survival.[12] In a novel experiment, the scientists projected a school logo onto a petri dish containing the organisms, which accreted beneath the lighted region, forming the logo in bacteria.[12] The authors speculate that such motility allows the cyanobacteria to seek light sources to support the colony.[12] In both light and dark conditions, the cyanobacteria form clumps that then expand outwards, with individual members remaining connected to the colony via long tendrils. This may be a protective mechanism that affords evolutionary benefit to the colony in harsh environments where mechanical forces act to tear apart the microbial mats. Thus these sometimes elaborate structures, constructed by microscopic organisms working somewhat in unison, are a means of providing shelter and protection from a harsh environment.

Fossil record

Some Archean rock formations show macroscopic similarity to modern microbial structures, leading to the inference that these structures represent evidence of ancient life, namely stromatolites. However, others regard these patterns as being due to natural material deposition or some other abiogenic mechanism. Scientists have argued for a biological origin of stromatolites due to the presence of organic globule clusters within the thin layers of the stromatolites, of aragonite nanocrystals (both features of current stromatolites),[11] and because of the persistence of an inferred biological signal through changing environmental circumstances.[13][14]

Stromatolites are a major constituent of the fossil record of the first forms of life on earth.[15] They peaked about 1.25 billion years ago[13] and subsequently declined in abundance and diversity,[16] so that by the start of the Cambrian they had fallen to 20% of their peak. The most widely supported explanation is that stromatolite builders fell victim to grazing creatures (the Cambrian substrate revolution); this theory implies that sufficiently complex organisms were common over 1 billion years ago.[17][18][19] Another hypothesis is that protozoans like the foraminifera were responsible for the decline.[20]

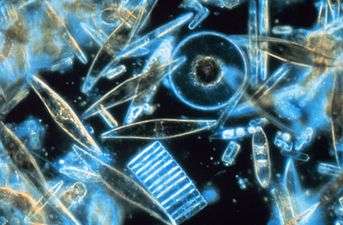

Proterozoic stromatolite microfossils (preserved by permineralization in silica) include cyanobacteria and possibly some forms of the eukaryote chlorophytes (that is, green algae). One genus of stromatolite very common in the geologic record is Collenia.

The connection between grazer and stromatolite abundance is well documented in the younger Ordovician evolutionary radiation; stromatolite abundance also increased after the end-Ordovician and end-Permian extinctions decimated marine animals, falling back to earlier levels as marine animals recovered.[21] Fluctuations in metazoan population and diversity may not have been the only factor in the reduction in stromatolite abundance. Factors such as the chemistry of the environment may have been responsible for changes.[22][23]

While prokaryotic cyanobacteria reproduce asexually through cell division, they were instrumental in priming the environment for the evolutionary development of more complex eukaryotic organisms.[15] Cyanobacteria (as well as extremophile Gammaproteobacteria) are thought to be largely responsible for increasing the amount of oxygen in the primeval earth's atmosphere through their continuing photosynthesis (see Great Oxygenation Event). Cyanobacteria use water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight to create their food. A layer of mucus often forms over mats of cyanobacterial cells. In modern microbial mats, debris from the surrounding habitat can become trapped within the mucus, which can be cemented together by the calcium carbonate to grow thin laminations of limestone. These laminations can accrete over time, resulting in the banded pattern common to stromatolites. The domal morphology of biological stromatolites is the result of the vertical growth necessary for the continued infiltration of sunlight to the organisms for photosynthesis. Layered spherical growth structures termed oncolites are similar to stromatolites and are also known from the fossil record. Thrombolites are poorly laminated or non-laminated clotted structures formed by cyanobacteria, common in the fossil record and in modern sediments.[11] There is evidence that thrombolites form in preference to stomatolites when foraminifera are part of the biological community.[24]

The Zebra River Canyon area of the Kubis platform in the deeply dissected Zaris Mountains of south western Namibia provides an extremely well exposed example of the thrombolite-stromatolite-metazoan reefs that developed during the Proterozoic period, the stromatolites here being better developed in updip locations under conditions of higher current velocities and greater sediment influx.[25]

Modern occurrence

Modern stromatolites are mostly found in hypersaline lakes and marine lagoons where extreme conditions due to high saline levels prevent animal grazing. One such location is Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve, Shark Bay in Western Australia where excellent specimens are observed today, Pampa del Tamarugal National Reserve in Chile and another is Lagoa Salgada ("Salty Lake"), in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, where modern stromatolites can be observed as bioherm (domal type) and beds. Inland stromatolites can also be found in saline waters in Cuatro Ciénegas, a unique ecosystem in the Mexican desert, and in Lake Alchichica, a maar lake in Mexico's Oriental Basin. The only open marine environment where modern stromatolites are known to prosper is the Exuma Cays in the Bahamas.[26][27]

In 2010, a fifth type of Chlorophyll, namely Chlorophyll f, was discovered by Dr. Min Chen from stromatolites in Shark Bay.[28]

Modern freshwater stromatolites

Laguna Bacalar in Mexico's southern Yucatán Peninsula in the state of Quintana Roo, has an extensive formation of living giant microbialites (that is, stromatolites or thrombolites). The microbialite bed is over 10 km (6.2 mi) long with a vertical rise of several meters in some areas. These may be the largest sized living freshwater microbialites, or any organism, on Earth.[29]

Crater Lake Alchichica in Puebla Mexico has two distinct morphologic generations of stromatolites: Columnar-dome like structures, rich in aragonite, forming near the shore line, dated back to 1100 ybp and Spongy-cauliflower like thrombolytic structures that dominate the lake from top to the bottom, mainly composed of Hydromagnesite, Huntite, Calcite and dated back to 2800 ybp.

A little farther to the south, a 1.5 km stretch of reef-forming stromatolites (primarily of the genus Scytonema) occurs in Chetumal Bay in Belize, just south of the mouth of the Rio Hondo and the Mexican border.[30]

Freshwater stromatolites are found in Lake Salda in southern Turkey. The waters are rich in magnesium and the stromatolite structures are made of hydromagnesite.[31]

Another pair of instances of freshwater stromatolites are at Pavilion and Kelly Lakes in British Columbia, Canada. Pavilion Lake has the largest known freshwater stromatolites and has been researched by NASA as part of xenobiology research.[32] NASA, the Canadian Space Agency and numerous universities from around the world are collaborating on a project centered on studying microbialite life in the lakes. Called the "Pavilion Lake Research Project" (PLRP) its aim is to study what conditions on the lakes' bottoms are most likely to harbor life and develop a better hypothesis on how environmental factors affect microbialite life. The end goal of the project is to better understand what conditions would be more likely to harbor life on other planets.[33] There is a citizen science project online called "MAPPER" where anyone can help sort through thousands of photos of the lake bottoms and tag microbialites, algae and other lake bed features.[34]

Microbialites have been discovered in an open pit pond at an abandoned asbestos mine near Clinton Creek, Yukon, Canada.[35] These microbialites are extremely young and presumably began forming soon after the mine closed in 1978. The combination of a low sedimentation rate, high calcification rate, and low microbial growth rate appears to result in the formation of these microbialites. Microbialites at an historic mine site demonstrates that an anthropogenically constructed environment can foster microbial carbonate formation. This has implications for creating artificial environments for building modern microbialites including stromatolites.

A very rare type of non-lake dwelling stromatolite lives in the Nettle Cave at Jenolan Caves, NSW, Australia.[36] The cyanobacteria live on the surface of the limestone, and are sustained by the calcium rich dripping water, which allows them to grow toward the two open ends of the cave which provide light.[37]

Stromatolites composed of calcite have been found in both the Blue Lake in the dormant volcano, Mount Gambier and at least eight cenote lakes including the Little Blue Lake in the Lower South-East of South Australia.[38]

See also

- Banded iron formation

- Cuatro Ciénegas

- Cyanobacteria

- Gunflint Range

- Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve

- Microbially induced sedimentary structure

- Microbial mat

- Ojos de Mar

- Oncolite

- Thrombolite

References

- "Stromatolite". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Stromatolite". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- στρῶμα, λίθος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Stromatolites Archived 19 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Riding, R. (2007). "The term stromatolite: towards an essential definition". Lethaia. 32 (4): 321–330. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00550.x. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015.

- Lichen Stromatolites: Criterion for Subaerial Exposure and a Mechanism for the Formation of Laminar Calcretes (Caliche), Colin F. Klappa, Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, Vol. 49 (1979) No. 2. (June), Pages 387-400, Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Paleobotany: The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants, Edith L. Taylor, Thomas N. Taylor, Michael Krings, page Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Riding, R. (2007). "The term stromatolite: towards an essential definition". Lethaia. 32 (4): 321–330. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00550.x. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015.

- "Two-ton, 500 Million-year-old Fossil Of Stromatolite Discovered In Virginia, U.S." Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Grotzinger, John P.; Rothman, Daniel H. (3 October 1996). "An abiotic model for stromatolite morphogenesis". Nature. 383 (6599): 423–425. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..423G. doi:10.1038/383423a0.

- Lepot, Kevin; Karim Benzerara; Gordon E. Brown; Pascal Philippot (2008). "Microbially influenced formation of 2.7 billion-year-old stromatolites". Nature Geoscience. 1 (2): 118–21. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..118L. doi:10.1038/ngeo107.

- Biddanda, Bopaiah A.; McMillan, Adam C.; Long, Stephen A.; Snider, Michael J.; Weinke, Anthony D. (1 January 2015). "Seeking sunlight: rapid phototactic motility of filamentous mat-forming cyanobacteria optimize photosynthesis and enhance carbon burial in Lake Huron's submerged sinkholes". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 930. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00930. PMC 4561352. PMID 26441867.

- Allwood, Abigail; Grotzinger; Knoll; Burch; Anderson; Coleman; Kanik (2009). "Controls on development and diversity of Early Archean stromatolites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9548–9555. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9548A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903323106. PMC 2700989. PMID 19515817.

- Cradle of life: the discovery of earth's earliest fossils. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. 1999. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-691-08864-8.

- Garwood, Russell J. (2012). "Patterns In Palaeontology: The first 3 billion years of evolution". Palaeontology Online. 2 (11): 1–14. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- McMenamin, M. A. S. (1982). "Precambrian conical stromatolites from California and Sonora". Bulletin of the Southern California Paleontological Society. 14 (9&10): 103–105.

- McNamara, K.J. (20 December 1996). "Dating the Origin of Animals". Science. 274 (5295): 1993–1997. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1993M. doi:10.1126/science.274.5295.1993f. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Awramik, S.M. (19 November 1971). "Precambrian columnar stromatolite diversity: Reflection of metazoan appearance". Science. 174 (4011): 825–827. Bibcode:1971Sci...174..825A. doi:10.1126/science.174.4011.825. PMID 17759393.

- Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation" (PDF). In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P.H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers. 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Bernhard, J. M.; Edgcomb, V. P.; Visscher, P. T.; McIntyre-Wressnig, A.; Summons, R. E.; Bouxsein, M. L.; Louis, L.; Jeglinski, M. (28 May 2013). "Insights into foraminiferal influences on microfabrics of microbialites at Highborne Cay, Bahamas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (24): 9830–9834. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.9830B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221721110. PMC 3683713. PMID 23716649.

- Sheehan, P.M.; Harris, M.T. (2004). "Microbialite resurgence after the Late Ordovician extinction". Nature. 430 (6995): 75–78. Bibcode:2004Natur.430...75S. doi:10.1038/nature02654. PMID 15229600.

- Riding, R. (March 2006). "Microbial carbonate abundance compared with fluctuations in metazoan diversity over geological time" (PDF). Sedimentary Geology. 185 (3–4): 229–38. Bibcode:2006SedG..185..229R. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.12.015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Peters, Shanan E.; Husson, Jon M.; Wilcots, Julia (June 2017). "The rise and fall of stromatolites in shallow marine environments" (PDF). Geology. 45 (6): 487–490. doi:10.1130/G38931.1. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Nuwer, Rachel (30 May 2013). "What Happened to the Stromatolites, the Most Ancient Visible Lifeforms on Earth?". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Adams, E. W.; Grotzinger, J. P.; Watters, W. A.; Schröder, S.; McCormick, D. S.; Al-Siyabi, H. A. (2005). "Digital characterization of thrombolite-stromatolite reef distribution in a carbonate ramp system (terminal Proterozoic, Nama Group, Namibia)" (PDF). AAPG Bulletin. 89 (10): 1293–1318. doi:10.1306/06160505005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "217-Stromatolites-Lee-Stocking-Exumas-Bahamas Bahamas". Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Feldmann M, McKenzie JA (April 1998). "Stromatolite-thrombolite associations in a modern environment, Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas". PALAIOS. 13 (2): 201–212. Bibcode:1998Palai..13..201F. doi:10.2307/3515490. JSTOR 3515490.

- Chen, M. .; Schliep, M. .; Willows, R. D.; Cai, Z. -L.; Neilan, B. A.; Scheer, H. . (2010). "A Red-Shifted Chlorophyll". Science. 329 (5997): 1318–1319. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1318C. doi:10.1126/science.1191127. PMID 20724585.

- Gischler, E.; Gibson, M. & Oschmann, W. (2008). "Giant Holocene Freshwater Microbialites, Laguna Bacalar, Quintana Roo, Mexico". Sedimentology. 55 (5): 1293–1309. Bibcode:2008Sedim..55.1293G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2007.00946.x.

- Rasmussen, K.A.; Macintyre, I.G. & Prufert, L (March 1993). "Modern stromatolite reefs fringing a brackish coastline, Chetumal Bay, Belize". Geology. 21 (3): 199–202. Bibcode:1993Geo....21..199R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0199:MSRFAB>2.3.CO;2.

- Braithwaite, C. & Zedef V (November 1996). "Living hydromagnesite stromatolites from Turkey". Sedimentary Geology. 106 (3–4): 309. Bibcode:1996SedG..106..309B. doi:10.1016/S0037-0738(96)00073-5.

- Ferris FG, Thompson JB, Beveridge TJ (June 1997). "Modern Freshwater Microbialites from Kelly Lake, British Columbia, Canada". PALAIOS. 12 (3): 213–219. Bibcode:1997Palai..12..213F. doi:10.2307/3515423. JSTOR 3515423.

- Brady, A.; Slater, G.F.; Omelon, C.R.; Southam, G.; Druschel, G.; Andersen, A.; Hawes, I.; Laval, B.; Lim, D.S.S. (2010). "Photosynthetic isotope biosignatures in laminated micro-stromatolitic and non-laminated nodules associated with modern, freshwater microbialites in Pavilion Lake, B.C". Chemical Geology. 274 (1–2): 56–67. Bibcode:2010ChGeo.274...56B. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.03.016.

- "NASA - Help NASA Find Life On Mars With MAPPER". NASA. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Power, I.M., Wilson, S.A., Dipple, G.M., and Southam, G. (2011) Modern carbonate microbialites from an asbestos open pit pond, Yukon, Canada, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gbi.2011.9.issue-2/issuetoc Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Geobiology. 9: 180-195.

- Jenolan Caves Reserve Trust. "Nettle Cave Self-guided tour". Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Cox G, James JM, Leggett KEA, Osborne RAL (1989). "Cyanobacterially deposited speleothems: Subaerial stromatolites". Geomicrobiology Journal. 7 (4): 245–252. doi:10.1080/01490458909377870.

- Thurgate, Mia E. (1996). "The Stromatolites of the Cenote Lakes of the Lower South East of South Australia" (PDF). HELICTITE, Journal of Australasian Cave Research. 34 (1): 17. ISSN 0017-9973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

Further reading

- Grotzinger, John P.; Andrew H. Knoll (1999). "Stromatolites in Precambrian Carbonates: Evolutionary Mileposts or Environmental Dipsticks?". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 27: 313–58. Bibcode:1999AREPS..27..313G. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.313. PMID 11543060.

- Allwood, Abigail C.; Malcolm R. Walter; Balz S. Kamber; Craig P. Marshall; Ian W. Burch (2006). "Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia". Nature. 441 (7094): 714–8. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..714A. doi:10.1038/nature04764. PMID 16760969.

- Awramik, S.; Sprinkle, J. (1999). "Proterozoic stromatolites: the first marine evolutionary biota". Historical Biology. 13 (4): 241–253. doi:10.1080/08912969909386584.

- Farías, María E.; Rascovan, Nicolás; Toneatti, Diego M.; Albarracín, Virginia H.; Flores, María R.; Poiré, Daniel Gustavo; Collavino, Mónica Mariana; Aguilar, O. Mario; Vázquez, Martín; Polerecky, Lubos (2013). "The discovery of Stromatolites developing at 3570 m above sea level in a high-altitude volcanic lake Socompa, Argentinean Andes". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): 15. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853497F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053497. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3538587. PMID 23308236. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stromatolites. |

- "Stromatolites - Pilbara". Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Research Initiatives in Bahamian Stromatolites". Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Laguna Bacalar Institute". Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Stromatolite photo gallery, a teaching set from Ohio State University

- Another nice stromatolite gallery