Procaine

Procaine is a local anesthetic drug of the amino ester group. It is used primarily to reduce the pain of intramuscular injection of penicillin, and it is also used in dentistry. Owing to the ubiquity of the trade name Novocain, in some regions, procaine is referred to generically as novocaine. It acts mainly as a sodium channel blocker.[1] Today it is used therapeutically in some countries due to its sympatholytic, anti-inflammatory, perfusion-enhancing, and mood-enhancing effects.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Parenteral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | N/A |

| Metabolism | Hydrolysis by plasma esterases |

| Elimination half-life | 40–84 seconds |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.388 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

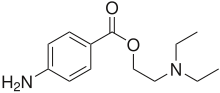

| Formula | C13H20N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 236.31 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Procaine was first synthesized in 1905,[3] shortly after amylocaine.[4] It was created by the chemist Alfred Einhorn who gave the chemical the trade name Novocaine, from the Latin nov- (meaning "new") and -caine, a common ending for alkaloids used as anesthetics. It was introduced into medical use by surgeon Heinrich Braun. Prior to the discovery of amylocaine and procaine, cocaine was a commonly used local anesthetic.[5] Einhorn wished his new discovery to be used for amputations, but for this surgeons preferred general anesthesia. Dentists, however, found it very useful.[6]

Pharmacology

.jpg)

The primary use for procaine is as an anaesthetic.

Procaine is used less frequently today, since more effective (and hypoallergenic) alternatives such as lidocaine (Xylocaine) exist. Like other local anesthetics (such as mepivacaine, and prilocaine), procaine is a vasodilator, thus is often coadministered with epinephrine for the purpose of vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction helps to reduce bleeding, increases the duration and quality of anesthesia, prevents the drug from reaching systemic circulation in large amounts, and overall reduces the amount of anesthetic required.[7] Unlike cocaine, a vasoconstrictor, procaine does not have the euphoric and addictive qualities that put it at risk for abuse.

Procaine, an ester anesthetic, is metabolized in the plasma by the enzyme pseudocholinesterase through hydrolysis into para-amino benzoic acid (PABA), which is then excreted by the kidneys into the urine.

A 1% procaine injection has been recommended for the treatment of extravasation complications associated with venipuncture, steroids, and antibiotics. It has likewise been recommended for treatment of inadvertent intra-arterial injections (10 ml of 1% procaine), as it helps relieve pain and vascular spasm.

Procaine is an occasional additive in illicit street drugs, such as cocaine. MDMA manufacturers also use procaine as an additive at ratios ranging from 1:1 up to 10% MDMA with 90% procaine, which can be life-threatening.[8]

Adverse effects

Application of procaine leads to the depression of neuronal activity. The depression causes the nervous system to become hypersensitive, producing restlessness and shaking, leading to minor to severe convulsions. Studies on animals have shown the use of procaine led to the increase of dopamine and serotonin levels in the brain.[9] Other issues may occur because of varying individual tolerance to procaine dosage. Nervousness and dizziness can arise from the excitation of the central nervous system, which may lead to respiratory failure if overdosed. Procaine may also induce weakening of the myocardium leading to cardiac arrest.[10]

Procaine can also cause allergic reactions causing individuals to have problems with breathing, rashes, and swelling. Allergic reactions to procaine are usually not in response to procaine itself, but to its metabolite PABA. Allergic reactions are in fact quite rare, estimated to have an incidence of 1 per 500,000 injections. About one in 3000 white North Americans is homozygous (i.e. has two copies of the abnormal gene) for the most common atypical form of the enzyme pseudocholinesterase,[11][12] and do not hydrolyze ester anesthetics such as procaine. This results in a prolonged period of high levels of the anesthetic in the blood and increased toxicity. However, certain populations in the world such as the Vysya community in India commonly have a deficiency of this enzyme.[12]

Synthesis

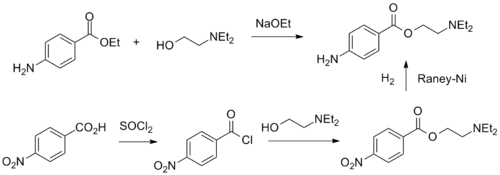

Procaine can be synthesized in two ways.

- The first consists of the direct reaction of the 4-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester with 2-diethylaminoethanol in the presence of sodium ethoxide.

- The second is by oxidizing 4-nitrotoluene to 4-nitrobenzoic acid, which is further reacted with thionyl chloride, the resulting acid chloride is then esterified with 2-diethylaminoethanol to give Nitrocaine. Finally, the nitro group is reduced by hydrogenation over Raney nickel catalyst.

See also

- Chloroprocaine

- Peter DeMarco

- Procaine blockade

References

- "Procaine (DB00721)". DrugBank. 2009-06-23.

- Hahn-Godeffroy JD (2011). "Procain-Reset: Ein Therapiekonzept zur Behandlung chronischer Erkrankungen" [Procaine reset: A therapy concept for the treatment of chronic diseases.]. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin [Swiss Journal of Integrative Medicine] (in German). 23 (5): 291–6. doi:10.1159/000332021.

- Ritchie JM, Greene NM (1990). "Local Anesthetics". In Gilman AG, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P (eds.). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (8th ed.). New York: Pergamon Press. p. 311. ISBN 0-08-040296-8.

- Minard R (18 October 2006). "The Preparation of the Local Anesthetic, Benzocaine, by an Esterification Reaction" (PDF).

Adapted from Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques: A Microscale Approach, Pavia, Lampman, Kriz & Engel, 1989.

- Ruetsch YA, Böni T, Borgeat A (August 2001). "From cocaine to ropivacaine: the history of local anesthetic drugs". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 1 (3): 175–82. doi:10.2174/1568026013395335. PMID 11895133.

- Drucker P (May 1985). "The discipline of innovation". Harvard Business Review. 3: 68.

- Sisk AL (1992). "Vasoconstrictors in local anesthesia for dentistry". Anesthesia Progress. 39 (6): 187–93. PMC 2148619. PMID 8250339.

- "Procaine". ecstasydata.org.

- Sawaki K, Kawaguchi M (November 1989). "Some correlations between procaine-induced convulsions and monoamines in the spinal cord of rats". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 51 (3): 369–76. doi:10.1254/jjp.51.369. PMID 2622091.

- "Novocain Official FDA information". drugs.com. August 2007.

- Ombregt L (2013). "Procaine: Principles of Treatment". A System of Orthopaedic Medicine (3rd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 83–115. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-3145-8.00005-3. ISBN 978-0-7020-3145-8.

- "Butyrylcholinesterase". OMIM. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Einhorn A, Fiedler K, Ladisch C, Uhlfelder E (1909). "Ueber p-Aminobenzoësäurealkaminester". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. 371 (2): 142–161. doi:10.1002/jlac.19093710204.

- Einhorn A, Höchst Ag U.S. Patent 812,554 DE 179627 DE 194748

Further reading

- Hahn-Godeffroy JD (2007). "Wirkungen und Nebenwirkungen von Procain: Was ist gesichert?". Komplement Integr. Med. 2: 32–4.