Baybayin

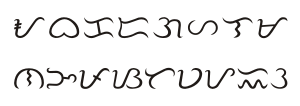

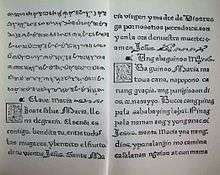

Baybayin (Tagalog pronunciation: [bai̯ˈba:jɪn]; pre-virama: , post-virama [krus-kudlit]: ; post-virama [pamudpod]: ), is a Brahmic script indigenous to the Philippines. Baybayin is an Umbrella term or hypernym of the scripts that has been widely used in traditional Tagalog domains and in other part of the Philippines.[4] There were many variants of Baybayin and the scripts continued to be used during the early part of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines until largely being supplanted by usage of the Latin alphabet. Baybayin is well known because it was carefully and extensively documented by scribes during the Spanish colonial era.[5]

| Baybayin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Old Tagalog, Sambali, Ilokano, Kapampangan, Bikolano, Pangasinense, Hanunuo, Buhid, Aborlan Tagbanwa, Palawano, Bisayan languages[1] |

Time period | c. 13th century (or older) –18th century[2][3] |

Parent systems | Proto-Sinaitic script

|

Child systems | In the Philippines: Tagalog script Sambal script Kur-itan script Kulitan script Basahan script Pangasinense script Hanunuo script Buhid script Tagbanwa script Ibalnan script Badlit script |

Sister systems | In other countries Balinese Batak Javanese (Hanacaraka) Lontara Sundanese Rencong Rejang |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Tglg, 370 |

Unicode alias | Tagalog |

Unicode range | U+1700–U+171F |

It is one of a number of individual writing systems used in Southeast Asia, nearly all of which are abugidas where any consonant is pronounced with the inherent vowel a following it—diacritics being used to express other vowels. Many of these writing systems descended from ancient writings used in India over 2000 years ago.

The Archives of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, one of the largest archives in the Philippines, currently possesses the world's biggest collection of ancient writings in Baybayin script.[4][6][7][8] The chambers which house the scripts are part of a tentative nomination to UNESCO World Heritage List that is still being deliberated on, along with the entire campus of the University of Santo Tomas.

Overview

Name

The term baybayín means "to write or to syllabize" in Tagalog.

On occasion, "baybayin" refers to other indigenous writing in the Philippines that are Abugida, including Buhid, Hanunó'o, Tagbanwa (Apurahuano), Kulitan, and others. Cultural organizations such as Sanghabi and the Heritage Conservation Society recommend that the collection of distinct scripts used by various indigenous groups in the Philippines, including baybayin, be called suyat, which a neutral term for any script.[9] While Jay Enage and other new advocates recommend that our writing system which is Abugida will be called "baybayin".

Some have incorrectly attributed the name Alibata to it,[10][11] but that term was coined by Paul Rodríguez Verzosa[12] after the arrangement of letters of the Arabic alphabet (alif, ba, ta (alibata), "f" having been eliminated for euphony's sake).[13] For the Visayans, it is called Kudlit-kabadlit.[14]

Origins

Evidence seems strong for Baybayin to be ultimately of Gujarati origin. [15] Its immediate ancestor was very likely a South Sulawesi script, probably Old Makassar or a close ancestor. This is because of the lack of coda consonant markers in Baybayin. Philippine and Gujarati languages have coda consonants, so it is unlikely that their indication would have been dropped had Baybayin been based directly on a Gujarati model. South Sulawesi languages, however, lack coda consonants and there is no way of representing them in the Bugis and Makassar scripts. The most likely explanation for the absence of coda consonant markers in Baybayin is therefore that its direct ancestor was a South Sulawesi script. Sulawesi lies directly to the south of the Philippines and these is evidence of trade routes between the two. Baybayin must therefore have been developed in the Philippines in the fifteenth century CE as the Bugis-Makassar script was developed in South Sulawesi no earlier than 1400 CE.[16] However, Geoff Wade has argued that the ancestor of the Baybayin script was a Cham script.

Influence of Greater India

Historically Southeast Asia was under the influence of Ancient India, where numerous Indianized principalities and empires flourished for several centuries in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Cambodia and Vietnam. The influence of Indian culture into these areas was given the term indianization.[17] French archaeologist, George Coedes, defined it as the expansion of an organized culture that was framed upon Indian originations of royalty, Hinduism and Buddhism and the Sanskrit dialect.[18] This can be seen in the Indianization of Southeast Asia, spread of Hinduism and Buddhism. Indian diaspora, both ancient (PIO) and current (NRI), played an ongoing key role as professionals, traders, priests and warriors.[19][20][21][21] Indian honorifics also influenced the Malay, Thai, Filipino and Indonesian honorifics.[22] Examples of these include Raja, Rani, Maharlika, Datu, etc. which were transmitted from Indian culture to Philippines via Malays and Srivijaya empire.

Kawi

The Kawi script originated in Java, and was used across much of Maritime Southeast Asia. It is a legal document with the inscribed date of Saka era 822, corresponding to April 21, 900 AD Laguna Copperplate Inscription. It was written in the Kawi script in a variety of Old Malay containing numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin is ambiguous between Old Javanese and Old Tagalog.

A second example of Kawi script can be seen on the Butuan Ivory Seal, though it has not been dated.

An earthenware burial jar, called the "Calatagan Pot," found in Batangas is inscribed with characters strikingly similar to Baybayin, and is claimed to have been inscribed ca. 1300 AD. However, its authenticity has not yet been proven.

One hypothesis therefore reasons that, since Kawi is the earliest attestation of writing on the Philippines, then Baybayin may have descended from Kawi or vice versa. It is the kawi inspired ancient alphabet of the people of Baybay in the Lakanate of Lawan used to write letters to relatives in far places where they migrate. Scott mentioned the Bingi of Lawan siday (local epic) originally written in Baybay, a place in ancient Lawan. It is believed that there were at least 16 different types of writing systems present around the Philippines prior to our colonization. Baybayin is just one of them, which was said to be of widespread use among coastal groups such as the Tagalog, Bisaya, Iloko, Pangasinan, Bikol, and Pampanga around the 16th century.

History

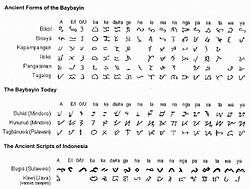

The best known evidence of where Baybayin came about is from the "abecedaries" evidence. It is an example of letters of the script arranged more or less in the order the Spaniards knew, reproduced by the Spanish and other observers in the different regions of Luzon and Visayas. Another source of evidence are the archival documents preserved and recovered. From these two sources, it is clear that the Baybayin scripts was used in Luzon, Palawan, Mindoro, as far as Pangasinan in the north, and in Ilocos, Panay, Leyte, and Iloilo, but there are no proof supporting that Baybayin reached Mindanao. From what is available, it seems clear that the Luzon and Palawan varieties have started to develop in different ways in the 1500s, way before the Spaniards conquered what we know today as the Philippines. This puts Luzon and Palawan as the oldest regions where Baybayin was and is used. It is also notable that the script used in Pampanga had already developed special shapes for four letters by the early 1600s, different from the ones used elsewhere. It is equally important to note that this ancient Kapampangan script is very different from the experiment called "modern Kulitan" which was taught in the late 1990s. So we can say that there were three somewhat distinct varieties of a single script in the late 1500s and 1600s, though they could not be described as three different scripts any more than the different styles of Latin script across medieval or modern Europe with their slightly different sets of letters and spelling systems.[4]

As mentioned earlier, the advent of the Baybayin in the Philippines was considered a fairly recent event in the 16th century and the Filipinos at that time believed that their Baybayin came from Borneo. This theory is supported by the fact that the Baybayin script could not show syllable final consonants, which are very common in most Philippine languages. (See Final Consonants) This indicates that the script was recently acquired and had not yet been modified to suit the needs of its new users. Also, this same shortcoming in the Baybayin was a normal trait of the script and language of the Bugis people of Sulawesi, which is directly south of the Philippines and directly east of Borneo. Thus most scholars believe that the Baybayin may have descended from the Buginese script or, more likely, a related lost script from the island of Sulawesi.

Although one of Ferdinand Magellan's shipmates, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote that the people of the Visayas were not literate in 1521, the Baybayin had already arrived there by 1567 when Miguel López de Legazpi reported that, "They [the Visayans] have their letters and characters like those of the Malays, from whom they learned them." Then, a century later Francisco Alcina wrote about:

The characters of these natives, or, better said, those that have been in use for a few years in these parts, an art which was communicated to them from the Tagalogs, and the latter learned it from the Borneans who came from the great island of Borneo to Manila, with whom they have considerable traffic... From these Borneans the Tagalogs learned their characters, and from them the Visayans, so they call them Moro characters or letters because the Moros taught them... [the Visayans] learned [the Moros'] letters, which many use today, and the women much more than the men, which they write and read more readily than the latter.[12]

According to other sources, the Visayans derived their writing system from those of Toba, Borneo, Celebes, Ancient Java, and from the Edicts of the ancient Indian emperor Ashoka.[23]

Baybayin was noted by the Spanish priest Pedro Chirino in 1604 and Antonio de Morga in 1609 to be known by most Filipinos, and was generally used for personal writings, poetry, etc. However, according to William Henry Scott, there were some datus from the 1590s who could not sign affidavits or oaths, and witnesses who could not sign land deeds in the 1620s.[24][25]

The only modern scripts that descended directly from the original Baybayin script through natural development are the Palaw'an script inherited from the Tagbanwa in Palawan, the Buhid and Hanunóo scripts in Mindoro, the ancient Kapampangan script used in the 1600s but has been supplanted by a constructed script called "modern Kulitan", and of course the Tagalog script. There is no evidence for any other regional scripts; like the modern Kulitan experiment in Pampanga. Any other scripts are recent inventions based on one or another of the abecedaries from old Spanish descriptions.[4]

Characteristics

The writing system is an abugida system using consonant-vowel combinations. Each character, written in its basic form, is a consonant ending with the vowel "A". To produce consonants ending with the other vowel sounds, a mark is placed either above the consonant (to produce an "E" or "I" sound) or below the consonant (to produce an "O" or "U" sound). The mark is called a kudlit. The kudlit does not apply to stand-alone vowels. Vowels themselves have their own glyphs.

There is only one symbol or character for Da or Ra as they were allophones in many languages of the Philippines, where Ra occurred in intervocalic positions and Da occurred elsewhere. The grammatical rule has survived in modern Filipino, so that when a d is between two vowels, it becomes an r, as in the words dangál (honour) and marangál (honourable), or dunong (knowledge) and marunong (knowledgeable), and even raw for daw (he said, she said, they said, it was said, allegedly, reportedly, supposedly) and rin for din (also, too) after vowels.[12] This variant of the script is not used for Ilokano, Pangasinan, Bikolano, and other Philippine languages to name a few, as these languages have separate symbols for Da and Ra.

As well the same letter is used to represent the Pa and Fa (or Pha), Ba and Va, Sa and Za which were also allophonic.

Beside these phonetic considerations, the script is monocameral and does not use letter case for distinguishing proper names or initials of words starting sentences.

Writing materials

Traditionally, baybayin was written upon palm leaves with styli or upon bamboo with knives.[26] The curved shape of the letter forms of baybayin is a direct result of this heritage; straight lines would have torn the leaves.[27] During the era of Spanish colonization, most baybayin began being written with ink on paper, but in some parts of the country the traditional art form has been retained.[28]

Two styles of writing

Virama Kudlit "style"

The original writing method was particularly difficult for the Spanish priests who were translating books into the vernaculars. Because of this, Francisco López introduced his own kudlit in 1620, called a sabat or krus, that cancelled the implicit a vowel sound. The kudlit was in the form of a "+" sign,[29] in reference to Christianity. This cross-shaped kudlit functions exactly the same as the virama in the Devanagari script of India. In fact, Unicode calls this kudlit the Tagalog Sign Virama. See sample above in Characteristics Section.

The confusion over the use of marks may have contributed to the demise of Baybayin over time. The desire of Francisco Lopez (1620) for Baybayin to conform to the Spanish alfabetos paved the way for the invention of a cross sign. Such introduction was uniquely a standalone event that was blindly copied by succeeding writers up to the present. Sevilla and Alvero (1939) said, "The marks required in the formation of syllables are: the tuldok or point (.) and the bawas or minus sign (-)." The bawas or minus sign (-) that is placed before the script to remove the paired vowel appears more logical than the cross or plus sign (+) of Lopez.[25]

"Nga" character

A single character represented "nga". The current version of the Filipino alphabet still retains "ng" as a digraph.

Punctuation

Words written in baybayin were written in a continuous flow, and the only form of punctuation was a single vertical or slanted line (), or more often, a pair of vertical or slanted lines (). These lines (similar to danda signs in other Indic abugidas) fulfill the function of a comma, period, or unpredictably separate sets of words.[12]

Usage

Pre-colonial and colonial usage

Baybayin historically was used in Tagalog and to a lesser extent Kapampangan speaking areas. Its use spread to Ilokanos when the Spanish promoted its use with the printing of Bibles. Among the earliest literature on the orthography of Visayan languages were those of Jesuit priest Ezguerra with his Arte de la lengua bisaya in 1747[30] and of Mentrida with his Arte de la lengua bisaya: Iliguaina de la isla de Panay in 1818 which primarily discussed grammatical structure.[31] Based on the differing sources spanning centuries, the documented syllabaries also differed in form.

The Ticao stone inscription, also known as the Monreal stone or Rizal stone, is a limestone tablet that contains Baybayin characters. Found by pupils of Rizal Elementary School on Ticao Island in Monreal town, Masbate, which had scraped the mud off their shoes and slippers on two irregular shaped limestone tablets before entering their classroom, they are now housed at a section of the National Museum of the Philippines, which weighs 30 kilos, is 11 centimeters thick, 54 cm long and 44 cm wide while the other is 6 cm thick, 20 cm long and 18 cm wide.[32][33]

Usage in Traditional Seals

Like Japan and Korea, the Philippines also had a sealing culture prior to Spanish colonization. However, when the Spaniards succeeded in colonizing the islands, they abolished the practice and burned all documents they captured from the natives while forcefully establishing a Roman Catholic-based rule. Records on Philippine seals were forgotten until in the 1970s when actual ancient seals made of ivory were found in an archaeological site in Butuan. The seal, now known as the Butuan Ivory Seal, has been declared as a National Cultural Treasure. The seal is inscribed with the word "Butwan" through a native baybayin script. The discovery of the seal proved the theory that pre-colonial Filipinos, or at least in coastal areas, used seals on paper. Before the discovery of the seal, it was only thought that ancient Filipinos used bamboo, metal, bark, and leaves for writing. The presence of paper documents in the classical era of the Philippines is also backed by a research of Otley Beyer stating that Spanish friars 'boasted' about burning ancient Philippine documents with baybayin inscriptions, one of the reasons why ancient documents from the Philippines are almost non-existent in present time. The ivory seal is now housed at the National Museum of the Philippines. Nowadays, younger generations are trying to revive the usage of seals, notably in signing pieces of art such as drawings, paintings, and literary works.[34]

Modern Usage

_Baybayin.jpg)

A number of legislative bills have been proposed periodically aiming to promote the writing system, among them is the "National Writing System Act" (House Bill 1022[35]/Senate Bill 433[36]). In 2018 the House of Representatives approved Baybayin as the national writing system. [37] It is used in the most current New Generation Currency series of the Philippine peso issued in the last quarter of 2010. The word used on the bills was "Pilipino" ().

It is also used in Philippine passports, specifically the latest e-passport edition issued 11 August 2009 onwards. The odd pages of pages 3–43 have "" ("Ang katuwiran ay nagpapadakila sa isang bayan"/"Righteousness exalts a nation") in reference to Proverbs 14:34.

The lyrics of Lupang Hinirang in Baybayin rendering.

The lyrics of Lupang Hinirang in Baybayin rendering. Flag of Katipunan in Magdiwang faction, with the Baybayin ka letter.

Flag of Katipunan in Magdiwang faction, with the Baybayin ka letter..svg.png) Seal of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, with the two Baybayin ka and pa letters in the center.

Seal of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, with the two Baybayin ka and pa letters in the center. Emblem of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, with a Baybayin ka in the center.

Emblem of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, with a Baybayin ka in the center..svg.png) Logo of the National Library of the Philippines. The Baybayin text reads as karunungan (ka r(a)u n(a)u nga n(a), wisdom).

Logo of the National Library of the Philippines. The Baybayin text reads as karunungan (ka r(a)u n(a)u nga n(a), wisdom). Logo of the National Museum of the Philippines, with a Baybayin pa letter in the center, in a traditional rounded style.

Logo of the National Museum of the Philippines, with a Baybayin pa letter in the center, in a traditional rounded style. Logo of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, with three rotated occurrences of the Baybayin ka letter.

Logo of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, with three rotated occurrences of the Baybayin ka letter. The insignia of the Order of Lakandula contains an inscription with Baybayin characters represents the name Lakandula, read counterclockwise from the top.

The insignia of the Order of Lakandula contains an inscription with Baybayin characters represents the name Lakandula, read counterclockwise from the top.

Characters

| Independent vowels | Base consonants (with implicit vowel a) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a |

i/e |

u/o |

ka |

ga |

nga |

ta |

da/ra |

na |

pa/fa |

ba/va |

ma |

ya |

la |

wa |

sa/za |

ha | |||

vowels

|

k

|

g

|

ng

|

t

|

d/r

|

n

|

p/f

|

b/v

|

m

|

y

|

l

|

w

|

s/z

|

h

|

Note that the first row of clusters (with virama) "+" were a late addition to the original script introduced by Spaniards. And the other one " ᜴" was introduced by Antoon Postma.

Punctuation and spelling

Baybayin writing makes use of only two punctuation marks (originally only one), the Philippine single () (acting today as a comma, or verse splitter in poetry) and double punctuation () (main punctuation, acting today as a period or end of paragraph), which are similar to single and double danda signs in other Brahmic scripts. These signs (which may be presented vertically like Indic dandas, or slanted like forward slashes) are unified across Philippines scripts and were encoded by Unicode in the Hanunóo script block.[38] Space separation of words was historically not used on traditional supports, but is common today.

Example sentences

-

- Yamang ‘di nagkakaunawaan, ay mag-pakahinahon.

- Remain calm in disagreements.

-

- Magtanim ay 'di birò.

- Planting is not a joke.

- ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜃᜊᜆᜀᜈ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜉᜄ᜔ᜀᜐ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜊᜌᜈ᜔

Ang kabataan ang pag-asa ng bayan

The youth is the hope of the country

-

- Mámahalin kitá hanggáng sa pumutí ang buhók ko.

- I will love you until my hair turns white.

Collation

- In the Doctrina Christiana, the letters of Baybayin were collated (without any connection with other similar script, except sorting vowels before consonants) as:

- A, U/O, I/E; Ha, Pa, Ka, Sa, La, Ta, Na, Ba, Ma, Ga, Da/Ra, Ya, NGa, Wa.[39]

- In Unicode the letters are collated in coherence with other Indic scripts, by phonetic proximity for consonnants:

- A, I/E, U/O; Ka, Ga, Nga; Ta, Da/Ra, Na; Pa, Ba, Ma; Ya, La, Wa, Sa, Ha.[40]

Examples

The Lord's Prayer (Ama Namin)

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English (1928 BCP)[41] (current Filipino Catholic version[42]) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Ama namin, sumasalangit ka, |

Our Father who art in heaven, |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English translation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Ang lahat ng tao'y isinilang na malaya Sila'y pinagkalooban ng katuwiran at budhi |

All human beings are born free They are endowed with reason and conscience |

Motto of the Philippines

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa. |

For God, For People, For Nature, and For Country. | |

| Isang Bansa, Isang Diwa |

One Country, One Spirit. |

Unicode

Baybayin was added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2002 with the release of version 3.2.

Block

The Unicode blocks for Baybayin covers Baybayin-Buhid, Baybayin-Hanunoó, Baybayin-Tagbanwa, and Baybayin-Tagalog.

Baybayin-Buhid Unicode range: U+1740–U+175F

| Buhid[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+174x | ᝀ | ᝁ | ᝂ | ᝃ | ᝄ | ᝅ | ᝆ | ᝇ | ᝈ | ᝉ | ᝊ | ᝋ | ᝌ | ᝍ | ᝎ | ᝏ |

| U+175x | ᝐ | ᝑ | ᝒ | ᝓ | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Baybayin-Hanunoó Unicode range: U+1720–U+173F

| Hanunoo[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+172x | ᜠ | ᜡ | ᜢ | ᜣ | ᜤ | ᜥ | ᜦ | ᜧ | ᜨ | ᜩ | ᜪ | ᜫ | ᜬ | ᜭ | ᜮ | ᜯ |

| U+173x | ᜰ | ᜱ | ᜲ | ᜳ | ᜴ | ᜵ | ᜶ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Baybayin-Tagbanwa Unicode range: U+1760–U+177F

| Tagbanwa[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+176x | ᝠ | ᝡ | ᝢ | ᝣ | ᝤ | ᝥ | ᝦ | ᝧ | ᝨ | ᝩ | ᝪ | ᝫ | ᝬ | ᝮ | ᝯ | |

| U+177x | ᝰ | ᝲ | ᝳ | |||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Baybayin-Tagalog Unicode range: U+1700–U+171F

| Tagalog[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+170x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+171x | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Keyboard

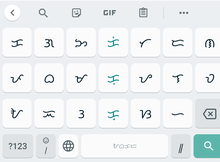

Gboard

The virtual keyboard app Gboard developed by Google for Android and iOS devices was updated on August 1, 2019[43] its list of supported languages. This includes all Unicode Baybayin blocks namely: Baybayin-Buhid as "Buhid", Baybayin-Hanunoó as "Hanunuo", Baybayin-Tagalog as "Filipino (Baybayin), and Baybayin-Tagbanwa as "Aborlan".[44] The Baybayin-Tagalog ("Filipino (Baybayin)") keyboard layout was intuitively designed when pressing the character, vowel markers for e/i and o/u, as well as the virama (vowel sound cancellation) are shown in the middle of the keyboard layout.

Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout with Baybayin

It is possible to type Baybayin directly from the keyboard without the need to use online typepads. The Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout[45] includes different sets of Baybayin layout for different keyboard users: QWERTY, Capewell-Dvorak, Capewell-QWERF 2006, Colemak, and Dvorak, all available in Microsoft Windows and GNU/Linux 32-bit and 64-bit installations.

The keyboard layout with Baybayin can be downloaded at this page.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baybayin. |

- Ancient Philippine scripts

- Buhid script

- Filipino orthography

- History of Indian influence on Southeast Asia

- Hanunuo script

- Kawi script

- Kulitan alphabet

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription

- Old Tagalog

- Suyat

- Tagbanwa script

References

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources". Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Tagalog (Baybayin)". SIL International. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Tagalog". Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "

- Scott 1984, pp. 57–58.

- Archives, University of Santo Tomas, archived from the original on May 24, 2013, retrieved June 17, 2012.

- "UST collection of ancient scripts in 'baybayin' syllabary shown to public", Inquirer, retrieved June 17, 2012.

- UST Baybayin collection shown to public, Baybayin, retrieved June 18, 2012.

- Protect all PH writing systems, heritage advocates urge Congress

- Halili, Mc (2004). Philippine history. Rex. p. 47. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- Duka, C (2008). Struggle for Freedom' 2008 Ed. Rex. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin, the Ancient Philippine script". MTS. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2008..

- Baybayin History, Baybayin, archived from the original on June 11, 2010, retrieved May 23, 2010.

- Eleanor, Maria (16 July 2011). "Finding the "Aginid"". philstar.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Miller, Christopher 2016. A Gujarati origin for scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines. Proceedings of Berkeley Linguistics Society 36:376-91

- Caldwell, Ian. 1988. Ten Bugis Texts; South Sulawesi 1300-1600. PhD thesis, Australian National University, p.17

- Acharya, Amitav. "The "Indianization of Southeast Asia" Revisited: Initiative, Adaptation and Transformation in Classical Civilizations" (PDF). amitavacharya.com.

- Coedes, George (1967). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Australian National University Press.

- Lukas, Helmut (May 21–23, 2001). "1 THEORIES OF INDIANIZATIONExemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia)". International SanskritConference.

- Krom, N.J. (1927). Barabudur, Archeological Description. The Hague.

- Smith, Monica L. (1999). ""INDIANIZATION" FROM THE INDIAN POINT OF VIEW: TRADE AND CULTURAL CONTACTS WITH SOUTHEAST ASIA IN THE EARLY FIRST MILLENNIUM C.E.". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 42. (11–17). JSTOR 3632296.

- Krishna Chandra Sagar, 2002, An Era of Peace, Page 52.

- Isabelo de los Reyes y Florentino, Las Islas Visayas en la Época de la Conquista (Segunda edición), Manila: 1889, Tipo-Litografía de Chofké y C.a, p. 82.

- Scott 1984, p. 210

- The Life, Death, and Resurgence of Baybayin

- Filipinas. Filipinas Pub. 1995-01-01. p. 60.

- "Cochin Palm Leaf Fiscals". Princely States Report > Archived Features. 2001-04-01. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- Lazaro, David (2009-10-23). "The Fundamentals of Baybayin". BakitWhy. Retrieved 2017-01-25 – via The Bathala Project.

- Tagalog script Archived August 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 2, 2008.

- P. Domingo Ezguerra (1601–1670) (1747) [c. 1663]. Arte de la lengua bisaya de la provincia de Leyte. apendice por el P. Constantino Bayle. Imp. de la Compañía de Jesús.

- Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera (1884). Contribución para el estudio de los antiguos alfabetos filipinos. Losana.

- Muddied stones reveal ancient scripts

- Romancing the Ticao Stones: Preliminary Transcription, Decipherment, Translation, and Some Notes

- Nation Museum Collections Seals

- "House Bill 1022" (PDF). 17th Philippine House of Representatives. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Senate Bill 433". 17th Philippine Senate. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "House approves Baybayin as national writing system". Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Chapter 17: Indonesia and Oceania, Philippine Scripts" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. March 2020.

- "Doctrina Cristiana". Project Gutenberg.

- Unicode Baybayin Tagalog variant

- "The 1928 Book of Common Prayer: Family Prayer". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church

- techmagus. "Baybayin in Gboard App Now Available". Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- techmagus. "Activate and Use Baybayin in Gboard". Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- "Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout". techmagus™.

External links

- House Bill 160, aka National Script Act of 2011

- Ang Baybayin by Paul Morrow

- Unicode Tagalog Range 1700-171F (in PDF)

- Yet another Baybayin chart

- Baybayin online translator

- Baybayin video tutorial

- Baybayin Unicode Keyboard Layout for Mac OSX

- Snoworld™'s Baybayin Unicode Typepad

- Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout with Baybayin, for Microsoft Windows and GNU/Linux both 32-bit and 64-bit

- Baybayin Keyboard extension for ChromeOS (Chromebooks)

- Online Baybayin Library

- Baybayin mobile translator application

- Nordenx's Baybayin Unicode Typepad

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History. New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0226-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)