Ideogram

An ideogram or ideograph (from Greek ἰδέα idéa "idea" and γράφω gráphō "to write") is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language, and specific words or phrases. Some ideograms are comprehensible only by familiarity with prior convention; others convey their meaning through pictorial resemblance to a physical object, and thus may also be referred to as pictograms.

| Writing systems |

|---|

|

|

| Types |

|

| Related topics |

Terminology

In proto-writing, used for inventories and the like, physical objects are represented by stylized or conventionalized pictures, or pictograms. For example, the pictorial Dongba symbols without Geba annotation cannot represent the Naxi language, but are used as a mnemonic for reciting oral literature.[1] Some systems also use ideograms, symbols denoting abstract concepts.

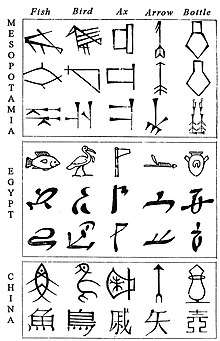

The term "ideogram" is often used to describe symbols of writing systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, Sumerian cuneiform and Chinese characters. However, these symbols represent elements of a particular language, mostly words or morphemes (so that they are logograms), rather than objects or concepts. In these writing systems, a variety of strategies were employed in the design of logographic symbols. Pictographic symbols depict the object referred to by the word, such as an icon of a bull denoting the Semitic word ʾālep "ox". Some words denoting abstract concepts may be represented iconically, but most other words are represented using the rebus principle, borrowing a symbol for a similarly-sounding word. Later systems used selected symbols to represent the sounds of the language, for example the adaptation of the logogram for ʾālep "ox" as the letter aleph representing the initial sound of the word, a glottal stop.

Many signs in hieroglyphic as well as in cuneiform writing could be used either logographically or phonetically. For example, the Akkadian sign DIĜIR (𒀭) could represent the god An, the word diĝir 'deity' or the word an 'sky'. The Akkadian counterpart ![]()

Although Chinese characters are logograms, two of the smaller classes in the traditional classification are ideographic in origin:

- Simple ideographs (指事字 zhǐshìzì) are abstract symbols such as 上 shàng "up" and 下 xià "down" or numerals such as 三 sān "three".

- Semantic compounds (会意字 huìyìzì) are semantic combinations of characters, such as 明 míng "bright", composed of 日 rì "sun" and 月 yuè "moon", or 休 xiū "rest", composed of 人 rén "person" and 木 mù "tree". In the light of the modern understanding of Old Chinese phonology, researchers now believe that most of the characters originally classified as semantic compounds have an at least partially phonetic nature.[2]

An example of ideograms is the collection of 50 signs developed in the 1970s by the American Institute of Graphic Arts at the request of the US Department of Transportation.[3] The system was initially used to mark airports and gradually became more widespread.

Mathematics

Mathematical symbols are a type of ideogram.[4]

Proposed universal languages

Inspired by inaccurate early descriptions of Chinese and Japanese characters as ideograms, many Western thinkers have sought to design universal written languages, in which symbols denote concepts rather than words. An early proposal was An Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language (1668) by John Wilkins. A recent example is the system of Blissymbols, which was proposed by Charles K. Bliss in 1949 and currently includes over 2,000 symbols.[5]

See also

- Emoji

- Heterogram (linguistics)

- Icon (computing)

- Lexigram

- List of symbols

- List of writing systems (including a sublist of ideographic systems)

- Logotype

- Therblig

- Traffic sign

References

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Boltz, William (1994). The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system. American Oriental Society. pp. 67–72, 149. ISBN 978-0-940490-78-9.

- Symbols and signs, AIGA.

- Rotman, Brian (2000). Mathematics as Sign: Writing, Imagining, Counting. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3684-8.

- Unger (2003), pp. 13–16.

- DeFrancis, John. 1990. The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1068-6

- Hannas, William. C. 1997. Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1892-X (paperback); ISBN 0-8248-1842-3 (hardcover)

- Unger, J. Marshall. 2003. Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning. ISBN 0-8248-2760-0 (trade paperback), ISBN 0-8248-2656-6 (hardcover)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ideograms. |

- The Ideographic Myth Extract from DeFrancis' book.

- American Heritage Dictionary definition

- Merriam-Webster OnLine definition