Yam Island (Queensland)

Yam Island, called Yama or Iama in the Kulkalgau Ya language or Turtle-backed Island in English, is an island of the Bourke Isles group of the Torres Strait Islands, located in the Tancred Passage of the Torres Strait in Queensland, Australia. The island is situated approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Thursday Island and measures about 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi). The island is also the locality of Iama Island within the Torres Strait Island Region local government area.[2] In the 2016 census, Iama Island had a population of 319 people.[1]

| Native name: Yama; Iama Nickname: Turtle-backed Island | |

|---|---|

.png) Landsat image of Yam Island | |

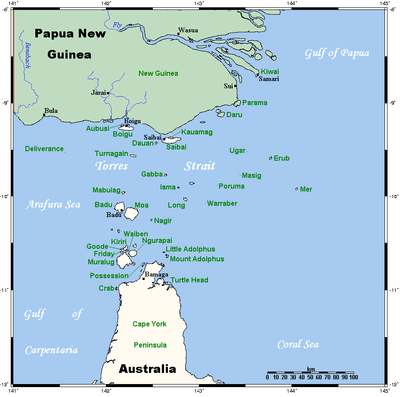

A map of the Torres Strait Islands showing Iama in the central waters of Torres Strait | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Tancred Passage, Northern Australia |

| Coordinates | 9°54′00″S 142°46′01″E |

| Archipelago | Bourke Isles group, Torres Strait Islands |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Torres Strait |

| Total islands | 1 |

| Area | 2 km2 (0.77 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

Australia | |

| State | Queensland |

| Local government area | Torres Strait Island Region |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 338 (2001 census) |

| Ethnic groups | Torres Strait Islanders |

| Iama Island Queensland | |

|---|---|

| Population | 319 (2016 census)[1] |

| • Density | 168/km2 (435/sq mi) |

| Area | 1.9 km2 (0.7 sq mi) |

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) |

| LGA(s) | Torres Strait Island Region |

| State electorate(s) | Cook |

| Federal Division(s) | Leichhardt |

Its indigenous language is Kulkalgau Ya, a dialect of the Western-Central Torres Strait language, Kalaw Lagaw Ya.

Prehistory

According to Mabuiag-Badu legend, Austronesian people from far-east Papua settled on Parema in the Fly Delta and married local trans-Fly women (of the group of peoples now called Gizra, Wipi, Bine, Meriam). Later they moved down to Torres Strait and settled on Yama, and then spread from there to different island groups. Westwards they went to Moa, Mabuiag, and there fought with local Aboriginal people and married some of the women, though apparently ‘purists’ who wanted to avoid further mixture moved north to Saibai, Boigu and Dauan. These initial settlements could have been anything up to around 2800 years ago. Eastwards they settled all the Central and Eastern Islands. They did not seem to have gone south to the Muralag group at this time. Much later, the Trans-Fly Meriam people of Papua moved to Mer, Erub and Ugar, taking most of the original inhabitants' land. These people, Western-Central Islanders, they called the Nog Le Common People, as opposed to the Meriam People, who are the noble people. Western-central Islanders in general are called the Gam Le Body People, as they are more thick-set on the whole than the slender Meriam.

This was the establishment of the Islanders as we know them today. Their languages are the mix of cultures mentioned above: the Western-Central language is an Australian (Paman) language with Austronesian and Papuan elements as cultural overlays, and the Eastern Language is dominantly Papuan, though with significant Australian and Austronesian elements.

According to Papuan legend [get reference : Lawrence 1998], a developing mud island near the mouth of a river to the south of the Fly Delta was first settled by people from Yama [in Kulkalgau Ya/Kalaw Lagaw Ya the name of the island is Dhaaru (Daru)], before the time that the Kiwai conquered the coastal parts of the South-West Fly Delta (perhaps at most around 700 years ago). The Yama had long-established trading and family contacts with the Trans-Fly Papuans, starting from the original Papuo-Austronesian settlements. When the Kiwai people started raiding and taking over territory, some of the Yama escaped to the Trans-Fly Papuans on the mainland, and others went across to Saibai, Boigu and Dauan to join their fellow Islanders there. However, the majority wanted to keep their tribal identity, and so decided to get as far away from the Kiwai as possible, and headed to the far south of Torres Strait, and settled on Moa, Muri and the Muralag group. A small core of Yama people stayed on Daru, and became virtually absorbed by the Daru Kiwai. The Kiwai call these people the Hiàmo (also Hiàma, Hiàmu - a Kiwai 'mispronunciation' of Yama, while the Yama people that moved to the Muralag group called themselves the Kauralaigalai, alt. Kauraraigalai (Kaurareg), in their modern dialect Kaiwaligal ‘Islanders’, in contrast to the Dhaudhalgal ‘Mainlanders of Papua’ and the Kawaigal or Ageyal ‘Aborigines of Australia’ (who are also Dhaudhalgal ‘Mainlanders’).

The Kaiwaligal (Kaurareg) and the Kulkalgal (Central Islanders) still have a close relationship, and traditionally considered themselves as closely related, much more than either is to the Mabuiag-Badu people or the Saibai-Dauan-Boigu people. The Kulkagal (Yama and others) have also kept their traditional ties with the Trans-Fly people, and also now with the Kiwai, who after their beginning as conquerors, have now become a part of the traditional trade network.

History

Before colonisation the inhabitants traded and fought widely in their sailing canoes. First recorded sighting by Europeans of Yam Island was by the Spanish expedition of Luís Vaez de Torres on 7 September 1606.[3] It was charted as Isla de Caribes (Island of Caribs) because of the tall warriors that were found there.[4] In 1792, they came aboard William Bligh's two ships seeking iron. Bligh named Tudu 'Warrior Island' after an attack they later made. The London Missionary Society established a station at Yam's western end making it possible for a permanent village with people settling around the mission. Many of the men took jobs on pearling luggers and a pearling station operated on Tudu during the 1870s with another at Nagi (Mount Ernest Island, southwest of Yam). Pacific Islanders working at Nagi station later settled on Yam. During the World War II, many Yam men enlisted in the army, forming C Company of the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion.

Despite their seafaring background, Yam people were fairly isolated from the outside world until well after the War. An airstrip was constructed in 1974 and the island's connection to the Torres Strait telephone exchange occurred in 1980. Yam has provided the Torres Strait with important political leaders including Getano Lui Senior (grandson of the first LMS teacher, Lui Getano Lifu) and Getano Lui Junior, former chairman of the Island Coordinating Council.

Yam Island State School was opened on 29 January 1985.[5] On 1 January 2007 it became the Yam Island Campus of the Tagai State College, which operates at 17 campuses throughout the Torres Strait.[5]

Education

Yam Island Campus is a primary (Early Childhood-6) campus of Tagai State College (9.8995°S 142.7696°E).[6][7]

Amenities

Torres Strait Island Regional Council operates the Dawita Cultural Centre on Church Road, and a library collection can be found here.[8]

Notable people

Notable people who are from or who have lived on Yam Island include:

- Ethel May Eliza Zahel (1877–1951), teacher and public servant.[9]

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Iama Island (SSC)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Iama Island - locality in Torres Strait Island Region (entry 46708)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Hilder, Brett The voyage of Torres, Brisbane, 1980, pp.75-77,80

- Don Diego Prado y Tovar, in his chronicles of the expedition, referred to the island as "isla de caribes muy grandes de a 12 palmos y medio" (island of very tall caribs of 12.5 spans) In the matter of the length of a span, palmo, there were different values in use in 1600; according to the sixteenth-century geographer and mathematician Petrus Apianus, a palmo was the stretch of four fingers, not including the thumb, or about 15cm. This would give the natives of this island a height of up to 190cm

- "Opening and closing dates of Queensland Schools". Queensland Government. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "State and non-state school details". Queensland Government. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Tagai State College - Yam Island Campus". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Iama (Dawita Cultural Centre)". Public Libraries Connect. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Lawrie, Margaret (1990). "Zahel, Ethel May Eliza (1877–1951)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

External links

Significant case law

- Yam Island Ergon Energy Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) (24 May 2005)

- David on behalf of the Iama People and Tudulaig v State of Queensland [2004] FCA 1576 (13 December 2004), Federal Court

- Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23, (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992), High Court.