W. Averell Harriman

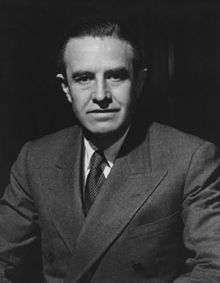

William Averell Harriman (November 15, 1891 – July 26, 1986), better known as Averell Harriman, was an American Democratic politician, businessman, and diplomat. The son of railroad baron E. H. Harriman, he served as Secretary of Commerce under President Harry S. Truman and later as the 48th Governor of New York. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952 and 1956, as well as a core member of the group of foreign policy elders known as "The Wise Men".

W. Averell Harriman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs | |

| In office April 4, 1963 – March 17, 1965 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | George C. McGhee |

| Succeeded by | Eugene V. Rostow |

| Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs | |

| In office December 4, 1961 – April 4, 1963 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Preceded by | Walter P. McConaughy |

| Succeeded by | Roger Hilsman |

| 48th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1955 – December 31, 1958 | |

| Lieutenant | George DeLuca |

| Preceded by | Thomas E. Dewey |

| Succeeded by | Nelson Rockefeller |

| Director of the Mutual Security Agency | |

| In office October 31, 1951 – January 20, 1953 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Harold Stassen |

| 11th United States Secretary of Commerce | |

| In office October 7, 1946 – April 22, 1948 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Henry A. Wallace |

| Succeeded by | Charles Sawyer |

| United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom | |

| In office April 30, 1946 – October 1, 1946 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | John Winant |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Douglas |

| United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union | |

| In office October 23, 1943 – January 24, 1946 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | William Standley |

| Succeeded by | Walter Bedell Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Averell Harriman November 15, 1891 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1986 (aged 94) Yorktown Heights, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (Before 1928) Democratic (1928–1986) |

| Spouse(s) | Kitty Lanier Lawrance (m. 1915; div. 1929) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents | E. H. Harriman (father) Mary Williamson Averell (mother) |

| Relatives | Mary Harriman Rumsey (sister) E. Roland Harriman (brother) |

| Education | Yale University (BA) |

| Signature | |

While attending Groton School and Yale University, he made contacts that led to creation of a banking firm that eventually merged into Brown Brothers Harriman & Co.. He owned parts of various other companies, including Union Pacific Railroad, Merchant Shipping Corporation, and Polaroid Corporation. During the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harriman served in the National Recovery Administration and on the Business Advisory Council before moving into foreign policy roles. After helping to coordinate the Lend-Lease program, Harriman served as the ambassador to the Soviet Union and attended the major World War II conferences. After the war, he became a prominent advocate of George F. Kennan's policy of containment. He also served as Secretary of Commerce, and coordinated the implementation of the Marshall Plan.

In 1954, Harriman defeated Republican Senator Irving Ives to become the Governor of New York. He served a single term before his defeat by Nelson Rockefeller in the 1958 election. Harriman unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination at the 1952 Democratic National Convention and the 1956 Democratic National Convention. Though Harriman had Truman's backing at the 1956 convention, the Democrats nominated Adlai Stevenson II in both elections.

After his gubernatorial defeat, Harriman became a widely respected foreign policy elder within the Democratic Party. He helped negotiate the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty during President John F. Kennedy's administration and was deeply involved in the Vietnam War during the Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson administrations. After Johnson left office in 1969, Harriman affiliated with various organizations, including the Club of Rome and the Council on Foreign Relations.

Early life and education

Better known as Averell Harriman, he was born in New York City, the son of railroad baron Edward Henry Harriman and Mary Williamson Averell. He was the brother of E. Roland Harriman and Mary Harriman Rumsey. Harriman was a close friend of Hall Roosevelt, the brother of Eleanor Roosevelt.

During the summer of 1899, Harriman's father organized the Harriman Alaska Expedition, a philanthropic-scientific survey of coastal Alaska and Russia that attracted 25 of the leading scientific, naturalist, and artist luminaries of the day, including John Muir, John Burroughs, George Bird Grinnell, C. Hart Merriam, Grove Karl Gilbert, and Edward Curtis, along with 100 family members and staff, aboard the steamship George Elder. Young Harriman would have his first introduction to Russia, a nation on which he would spend a significant amount of attention in his later life in public service.

He attended Groton School in Massachusetts before going on to Yale where he joined the Skull and Bones society.[1]:127,150–1 He graduated in 1913. After graduating, he inherited one of the largest fortunes in America and became Yale's youngest Crew coach.

Career

Business affairs

Using money from his father he established W.A. Harriman & Co banking business in 1922. In 1927 his brother Roland joined the business and the name was changed to Harriman Brothers & Company. In 1931, it merged with Brown Bros. & Co. to create the highly successful Wall Street firm Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. Notable employees included George Herbert Walker and his son-in-law Prescott Bush.

Harriman's main properties included Brown Brothers & Harriman & Co, Union Pacific Railroad, Merchant Shipbuilding Corporation, and venture capital investments that included the Polaroid Corporation. Harriman's associated properties included the Southern Pacific Railroad (including the Central Pacific Railroad), Illinois Central Railroad, Wells Fargo & Co., the Pacific Mail Steamship Co., American Ship & Commerce, Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktiengesellschaft (HAPAG), the American Hawaiian Steamship Co., United American Lines, the Guaranty Trust Company, and the Union Banking Corporation.

He served as Chairman of The Business Council, then known as the Business Advisory Council for the United States Department of Commerce in 1937 and 1939.[2]

Politics

Harriman's older sister, Mary Rumsey, encouraged Averell to leave his finance job and work with her and their friends, the Roosevelts, to advance the goals of the New Deal. Averell joined the NRA National Recovery Administration, the first government consumer rights group, marking the beginning of his political career.

Thoroughbred racing

Following the death of August Belmont Jr., in 1924, Harriman, George Walker, and Joseph E. Widener purchased much of Belmont's thoroughbred breeding stock. Harriman raced under the nom de course of Arden Farm. Among his horses, Chance Play won the 1927 Jockey Club Gold Cup. He also raced in partnership with Walker under the name Log Cabin Stable before buying him out. U.S. Racing Hall of Fame inductee Louis Feustel, trainer of Man o' War, trained the Log Cabin horses until 1926.[3] Of the partnership's successful runners purchased from the August Belmont estate, Ladkin is best remembered for defeating the European star Epinard in the International Special.

War seizures controversy

Harriman's banking business was the main Wall Street connection for German companies and the varied U.S. financial interests of Fritz Thyssen; who was a financial backer of the Nazi party until 1938. The Trading With the Enemy Act (enacted on October 6, 1917)[4] classified any business transactions for profit with enemy nations as illegal, and any funds or assets involved were subject to seizure by the U.S. government. The declaration of war on the U.S. by Hitler led to the U.S. government order on October 20, 1942 to seize German interests in the U.S. which included Harriman's operations in New York City.

The Harriman business interests seized under the act in October and November 1942 included:

- Union Banking Corporation (UBC) (from Thyssen and Brown Brothers Harriman)

- Holland-American Trading Corporation (from Harriman)

- Seamless Steel Equipment Corporation (from Harriman)

- Silesian-American Corporation (this company was partially owned by a German entity; during the war the Germans tried to take full control of Silesian-American. In response to that, the American government seized German-owned minority shares in the company, leaving the U.S. partners to carry on the portion of the business in the United States.)

The assets were held by the government for the duration of the war, then returned afterward; UBC was dissolved in 1951.

Compensation for wartime losses in Poland were based on prewar assets. Harriman, who owned vast coal reserves in Poland, was handsomely compensated for them through an agreement between the American and Polish governments. Poles who had owned little but their homes received negligible sums.

World War II diplomacy

Beginning in the spring of 1941, Harriman served President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a special envoy to Europe and helped coordinate the Lend-Lease program. He was present at the meeting between FDR and Winston Churchill at Placentia Bay, in August 1941, which yielded the Atlantic Charter – that set out American and British goals for the period following the end of World War II, before the U.S. was even involved in that war, in the form of a common declaration of principles that was eventually endorsed by all of the Allies.[5] Harriman was subsequently dispatched to Moscow to negotiate the terms of the Lend-Lease agreement with the Soviet Union in September 1941 together with the Canadian publishing millionaire Lord Beaverbrook who represented Great Britain.[6] Harriman tended to follow Beaverbrook's argument that since Germany had committed 3 million men to the invasion of the Soviet Union and hence the Soviets were doing the bulk of the fighting against the Third Reich, it was in the best interests of the Western powers to do everything to assist the Soviet Union.[6] The decision to aid the Soviet Union was taken against the advice of the U.S. ambassador in Moscow, Laurence Steinhardt, who right from the moment that Operation Barbarossa started on 22 June 1941 had been sending cables predicating the Soviet Union would be rapidly defeated and that any American aid would thus be wasted.[7] Likewise, General George Marshall was advising President Roosevelt that it was inevitable that Germany would crush the Soviet Union and predicted that the Wehrmacht would reach Lake Baikal by the end of 1941.[8]

The most important result of the Beaverbrook-Harriman mission to Moscow was their conclusion which was accepted by both Churchill and Roosevelt that the Soviet Union would not collapse by the end of 1941, and that if even the Soviet Union was defeated in 1942, keeping Soviet Russia fighting would impose major losses on the Wehrmacht which would only benefit the United States and Great Britain.[9] Harriman has been subsequently criticized for not imposing preconditions on American aid to the Soviet Union, but the American historian Gerhard Weinberg has defended him on this point, arguing that in 1941 it was Germany, not the Soviet Union, which represented the main danger to the United States.[6] Furthermore, Joseph Stalin told Harriman that he would refuse American aid if preconditions were attached, leaving Harriman with no alternatives on the issue.[6] Harriman believed if Germany defeated the Soviet Union, then all of the vast natural resources of the Soviet Union would be at the disposal of the Reich, making Germany far more powerful than what it already was, and it was in the best interests of the United States to deny those resources to the Reich.[6] In addition, he pointed out the defeat of the Soviet Union would free up 3 million men of the Wehrmacht for operations elsewhere while allowing Hitler to shift money and resources from his army to his navy, which could potentially threaten the United States.[9] Harriman told Roosevelt that if Operation Barbarossa was successful in 1941, then Hitler would almost certainly defeat Britain in 1942.[9] His promise of $1 billion in aid technically exceeded his brief. Determined to win over the doubtful American public, he used his own funds to purchase time on CBS radio to explain the program in terms of enlightened self-interest. Nonetheless, this skepticism persisted, and only lifted with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[10]

In a speech in 1972, Harriman stated: "Today people tend to forget that, in 1941, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill had one prime objective: to destroy Hitler's forces and win the war in a way that would be least costly in terms of human lives. For over a year, the British alone had borne the brunt of Nazi attacks; for their own self-preservation they wanted to keep Russia as a fighting ally. Roosevelt had yet another consideration in mind. In those early days of the war, he was fearful that we would eventually be drawn into the conflict, yet he still hoped that our participation could be limited to air and naval forces with a minimum of ground troops. We are all, to a considerable extent, the product of our experience: Roosevelt had a particular horror of the trench warfare of World War I and he wanted above all to prevent that fate from again befalling American fighting men. He hoped that, with our support, the Red Army would be able to keep the Axis forces engaged. The strength of the British divisions coupled with our own air and sea power might then make it unnecessary for the United States to commit major ground forces on the European continent".[11] The Beaverbrook-Harriman mission promised that the United States and Great Britain would supply the Soviet Union every month with 500 tanks and 400 air planes, plus tin, copper, and zinc.[12] However, the promised supplies had to arrive via the perilous "Murmansk run" through the Arctic Ocean, and only a tiny fraction was promised had in fact arrived by December 1941.[12]

On November 25, 1941 (twelve days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor), he noted that "The United States Navy is shooting the Germans—German submarines and aircraft at sea".[13] In 1941, a team of officers led by General Albert Wedemeyer on behalf of General Marshal drew up the Victory Program, whose premise was that the Soviet Union would be defeated that year, and that to defeat Germany would require the United States to raise by the summer of 1943 a force of 215 divisions comprising 8.7 million men.[14] The Harriman-Beaverbrook mission, whose more optimistic appraisal of Soviet fighting power ran contrary to the more pessimistic assessment, challenged one of the basic assumptions of the Victory Program. The Victory Program with its call for a 215-division army plus men for the Army Air Corps, the Navy and the Marines which would require massive amounts of equipment, leading to what was known as the Feasibility Dispute within different departments of the government.[15] To build the necessary weapons for such a massive force would require the government to essentially end all civilian production within the U.S, which was estimated would cause a 60% reduction in living standards.[15] Many in the government felt would impose a level of sacrifice that the American people would be unwilling to accept.[15] The Feasibility Dispute ended in 1942 with the "civilian" fraction triumphing over the military as Roosevelt decided upon what was known as the "90 division gamble".[15] Roosevelt decided that all of the evidence he received since the Harriman-Beaverbrook mission indicated that the Soviet Union would not be defeated as the Victory Program had assumed, and as such the 215 division force envisioned was not necessary and instead he would "gamble" with a 90 division force.[16]

In August of 1942, Harriman accompanied Churchill to the Moscow Conference to explain to Stalin why the western allies were carrying out operations in North Africa instead of opening the promised second front in France. The meeting was a difficult one with Stalin openly accusing Churchill to his face of lying to him and suggested that the British would not open a second front in Europe because of cowardice, sarcastically saying that the recent defeats suffered by the British 8th Army in North Africa showed how brave the British were against the Wehrmacht.[17] Harriman had spent much time after the meeting at the Kremlin reminding Churchill that the Allies needed the Soviet Union and to try not to take Stalin's remarks too personally, saying the fate of the world was hanging in balance.[17] On 24 June 1943, Harriman met with Churchill to tell him that Roosevelt did not want him to attend the up-coming summit meeting with Stalin, saying that it was important to allow Roosevelt who had never met Stalin to establish an "intimate understanding", which would be "impossible" if Churchill was there.[18] Churchill rejected this suggestion, sending a telegram to Roosevelt full of hurt feelings saying: "I do not underrate the use that enemy propaganda would make of a meeting between the heads of Soviet Russia and the United States at this juncture with the British Commonwealth and Empire excluded. It would be serious and vexatious, and many would be bewildered and alarmed thereby".[18] Roosevelt in his replys lied by saying that this just a "misunderstanding" and he would never wanted to exclude Churchill from the summit with Stalin.[19]

Harriman was appointed as United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union in October 1943.[10] In his 1975 memoir Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin, 1941-1946, Harriman wrote that Stalin was "the most inscrutable and contradictory character I have ever known", a mysterious man of "high intelligence and fantastic grasp of detail" who possessed much "shrewdness" and "surprising human sensitivity".[20] Harriman concluded that Stalin was "better informed than Roosevelt, more realistic than Churchill, in some ways the most effective of the war leaders. At the same time he was, of course, a murderous tyrant".[20] Harriman, who thoroughly enjoyed living in London, did not want to be U.S ambassador in Moscow and only reluctantly accepted the assignment in October 1943 after Roosevelt told him that he was the only man he wanted in Moscow.[21] Harriman was also reluctant to part with his mistress, Pamela Churchill, the wife of Randolph Churchill.[22] Through Harriman was one of the richest men in the United States, running a vast business empire comprising investments in railroads, aviation, banks, utilities, shipbuilding, oil production, steel manufacturing, and resorts, this in fact endeared him to the Soviets whom accurately recognized he represented American capitalist ruling class.[22] Nikita Khrushchev later told Harriman: "We like to do business with you, for you are the master and not the lackey".[22] Stalin viewed the United States through a Marxist prism, which shrewdly saw American Big Business as the puppeteers and American politicians as the puppets.[22]

At a three power conference in Moscow that took place between 19–30 October 1943, Harriman played a major role in representing United States as part of the American delegation headed by Secretary of State Cordell Hull while the Soviet delegation was headed by the Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov and the British delegation headed by the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden.[23] The main American demands at the Moscow Conference was to have a new international organization replace the League of Nations to be called the United Nations; to have Soviet Union to agree to adhere to the "unconditional surrender" formula adopted at the Casablanca conference (a major point given that the Soviets sometimes hinted that they were willing to sign a separate peace with Germany); and for the "Big Three" powers whom it was assumed would dominate the post-war world to be a "Big Four" as the Americans wanted China to stand alongside the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain as one of the world's dominant powers.[23] The demand for a "Big Four" instead of a "Big Three" turned out to the main difficulty at the Moscow conference as the British and Soviets did not consider China a major power in any sense.[23] As long as the Soviet Union was engaged in the war against Germany, they not did wish to antagonize Japan with whom they had signed a neutrality agreement with in 1941, and the Soviets objected that having Foo Ping Shen, the Chinese ambassador to Moscow, sign the proposed Four Power Declaration would cause tensions with Tokyo.[23] Eventually, after much patient diplomacy, Harriman won out, and a Four Power declaration was signed on 30 October 1943 by Hull, Eden, Molotov and Foo stating that the four permanent members of the United Nations Security Council would be the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and China.[23]

Besides for the Four Power declaration, the other issues at the Moscow conference were whether the United States would recognize the French National Committee of Liberation headed by General Charles de Gaulle as the French government-in-exile.[23] Roosevelt had a strong personal aversion to de Gaulle, and throughout the war, the Americans had an "anybody but de Gaulle" attitude. At Moscow, the Americans very reluctantly agreed to Eden's insistence that they extend some recognition to de Gaulle, through the Americans still refused to grant him full recognition, a matter which contributed much to de Gaulle's subsequent anti-Americanism.[23] The question of who the legitimate government of France was posed a major potential problem since the next year Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, was scheduled to take place. Presuming Overlord was successful, the question would arise over whom the Anglo-Americans would turn France over to. Nothing infuriated de Gaulle more than the implication that the Americans would not hand over France to his National Committee after the liberation. Tensions between Great Britain and the Soviet Union over the Arctic supply convoys were eased while the difficulties over supplies coming over Iran were left unresolved despite Harriman's best efforts at playing mediator.[23] On the matter of Germany, the Soviet Union agreed to the "unconditional surrender" formula while it agreed that after the war, Germany was to be disarmed and denazified.[23]

All of the delegations at the Moscow conference agreed that Germany was to be permanently disarmed after the war, which led to the question of whatever Germany should be also deindustrialized as well in order to ensure that Germany would never be able to build military weapons again; no consensus was reached over this issue.[24] The question of what Germany's borders were to be after the war was left unresolved, through everybody at the conference agreed that Germany was going to lose territory with the only question being just how much.[24] One matter where agreement was reached was with Austria as it was announced at the Moscow conference that the Anschluss of 1938 was to be undone and Austria would have its independence restored after the war.[25] Finally, in regards to the Reich, it was agreed that war crimes trials were to take place after the war with lesser war criminals to be tried in the nations where they had committed their crimes while the leaders of Germany were to be tried by a special court consisting of judges from the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union.[25] The communique in Moscow which announced that war crimes trials were going to be held after the war was intended primarily as a deterrent to those German officials presently engaged in war crimes as it was hoped that the prospect of facing a hangman's noose after the war might change their behavior.[25] As for Italy, it was agreed that the Soviet Union was to send a representative to the Allied Control Commission which governed the liberated parts of Italy and Italy was to pay reparations to the Soviet Union in the form of ships as much of the Italian merchant marine was to be handed over to the Soviet Union.[25] No agreement was reached over the question of the Soviet Union's borders after the war with the Soviets insisting that their post-war borders should be exactly where they were on 21 June 1941, a point that the American delegation and to a lesser extent British delegation resisted.[26]

At the Tehran Conference in late 1943 Harriman was tasked with placating a suspicious Churchill while Roosevelt attempted to gain the confidence of Stalin. The conference highlighted the divisions between the United States and Britain about the postwar world. Churchill was intent on maintaining Britain's empire and carving the postwar world into spheres of influence while the United States upheld the principles of self-determination as laid out in the Atlantic Charter. Harriman mistrusted the Soviet leader's motives and intentions and opposed the spheres approach as it would give Stalin a free hand in eastern Europe.[10] At the Tehran conference, Molotov finally promised Harriman what he long sought, namely that after Germany was defeated, the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan.[27] At Tehran, Roosevelt told Stalin that as a "practical man" who was planning to run for a fourth term in 1944 that he to think of Polish-American voters, but that he agreed that the Soviets could keep the part of Poland they had annexed in 1939, provided that this was kept a secret until the 1944 election.[28] Harriman felt that this was a mistake, as he regarded Roosevelt's statement that of course the Polish government have to accept the loss of this territory as being virtually agreeing to allow the Soviets to impose any government they wanted on Poland as it was unlikely that the Polish government-in-exile would agree.[28] At the same time, Harriman was jolted when Molotov admitted to him that there had been attempts at arranging a separate German-Soviet peace which would leave the Western Allies to face the full force of the Wehrmacht earlier in 1943, but that the Soviets had rejected the peace overtures.[29] The way in which Molotov phrased his account implied to Harriman that in the future the Soviets might be more receptive to such peace offers, which Harriman regarded as an attempt at blackmail.[29] On 22 January 1944, Harriman's daughter Kathleen, whom the British Foreign Office described as "the poor man's Mrs. Roosevelt" traveled to Katyn Forest to see the "evidence" that the Soviet authorities had produced meant to prove that the Katyn Forest massacre had been committed by the Germans in 1941, instead of the Soviets in 1940.[30] Since all of the available evidence suggested that the Soviets had in fact committed the Katyn Forest massacre in April 1940, Harriman later stated that he tried to avoid the subject, telling a Senate hearing "No, I do not recall the subject came up".[31]

Starting in February 1944, Harriman pressed Stalin to open U.S-Soviet staff talks to prepare for when the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan, only to be told this was "premature" as Stalin stated it would require at least 4 infantry divisions to invade Manchuria, which would not be possible given that the Soviets were fully involved in the war against Germany.[32] For the rest of 1944, Harriman pressed Molotov to bring the head of the Soviet Far Eastern Air Force to Moscow to open staff talks with the U.S military mission about establishing American air bases in either the Vladivostok area or in Kamchatka to allow American aircraft to bomb Japan.[32] Molotov refused to make any firm commitments about allowing American bombers to strike Japan from air bases in the Soviet Union.[32] Another major concern of the Roosevelt administration was in ensuring that the Chinese civil war did not resume with the end of World War II, and as such, the Americans sought a coalition government between the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang.[33] In connection with this, Harriman met Stalin on 10 June 1944 to get from him a rather generalized statement declaring his support for Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek as China's only leader and a promise that he would use his influence with Mao Zedong to pressure him to recognize Chiang.[34] In August 1944, Harriman sought permission for American aircraft flying supplies to the Armia Krajowa rebels fighting in the Warsaw Uprising to land at the Poltava airbase as otherwise the American aircraft would have no fuel to make it home.[35] On 16 August 1944, the Assistant Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Andrei Vyshinsky, told Harriman that "the Soviet government cannot of course object to English or American aircraft dropping arms in the region of Warsaw since this is an American or British affair. But they decidedly object to American or British aircraft, after dropping arms in the region of Warsaw, landing on Soviet territory, since the Soviet government does not wish to associate themselves either directly or indirectly with the adventure in Warsaw".[35] In a cable to Washington, Harriman wrote: "The Soviet Government's refusal is not based on operational difficulties nor on a denial of the conflict, but on ruthless political calculations".[36]

In the summer of 1944, Stalin promised Harriman that the Americans would be allowed to use air bases in the Soviet Far East to bomb Japan, but only if the Americans supplied the Soviet Air Force with hundreds of four engine bombers.[37] In September 1944, Stalin expressed much pique to Harriman that the recent Anglo-American communique issued at the Quebec Conference did not mention the Soviet Union, leading him to sarcastically state "if the United States and Great Britain desired to bring the Japanese to their knees without Russian participation, the Russians were ready to do this".[37] When Harriman protested it was impossible to include the Soviet Union in the plans for victory over Japan until the Soviets opened staff talks, Stalin assented.[32]

In early October 1944, the commanders of military forces in the Soviet Far East arrived in Moscow to begin staff talks with General John Deanne of the U.S. military mission.[37] At the same time, Stalin informed Harriman that Soviet entry into the war against Japan would require American approval of certain political conditions about the future of Manchuria, a point about which he did not elaborate upon.[38] On 14 December 1944, Stalin spelled out to Harriman what these political conditions were, namely that the Soviet Union be allowed to lease the Chinese Eastern Railroad and the ports on the Liaotung peninsula and for China to recognize the independence of Outer Mongolia.[39] In a thinly veiled threat, Stalin boasted to Harriman that the flat open plains of Manchuria and northern China were the perfect country for Soviet combined arms operations, expressing much confidence that the Red Army would have no difficulty defeating the Kwantung Army and that all of northern China would be under Soviet control once the Soviets declared war on Japan.[39] Essentially, Stalin was saying the Soviets would take whatever they wanted in China, regardless if they had an agreement with the United States or not.[39] At a dinner at the Kremlin during the visit of General de Gaulle to Moscow in December 1944, Harriman was disturbed by the way Stalin toasted Chief Air Marshal Alexander Novikov in front of him and de Gaulle, saying: "He has created a wonderful air force. But if he doesn't do his job properly then we'll kill him".[40]

Harriman also attended the Yalta Conference, where he encouraged taking a stronger line with the Soviet Union—especially on questions of Poland.[41] The American delegation at the Yalta conference stayed at the luxurious Livadia Palace overlooking the Black Sea, and Harriman was given a room of his own to stay, a sign of presidential favor as most of the American delegation had to sleep five men to a room owing to a surplus of delegates and a lack of space in the Livadia Palace.[42] The Livadia palace had been built in 1910-11 as a summer residence for the Emperor Nicholas II and his family, and was designed to house only 61 people, hence the presence of a 215-strong American delegation literally overwhelmed its facilities.[43] The Livadia palace had only six toilets, one of which was reserved exclusively for the president, which made for some discomfort as the American delegation numbered 215 people.[42]

On 8 February 1945, Roosevelt, Harriman and Charles "Chip" Bohlen who served as the interpreter met Stalin, Molotov and the translator Vladimir Pavlov to discuss the Soviet entry into the war against Japan.[44] During the meeting, it was agreed that the Kuriles islands and the southern half of Sahkalin island were to be annexed by the Soviets.[45] Without consulting Chiang, Roosevelt agreed to the Soviet demands for a role in managing the port of Dairen and to own Chinese Eastern Railroad, through with the regard to the former he felt that Dairen should be internationalized.[46] Roosevelt stated that he could not inform the Chinese at present because whatever was said to them "was known to the whole world in twenty-four hours", but he would tell them when the time was right; much to Harriman's mirth, Stalin promised he could "guarantee the security of the Supreme Soviet!"[47] Once Molotov presented a draft note to Harriman about the future of Manchuria, Harriman complained that the Soviet draft stated the Soviet Union would lease both Dairen and Port Arthur and manage not only the Chinese Eastern Railroad, but the South Manchuria Railroad as well.[48] Harriman objected, stating that Roosevelt wanted the ports on the Liaotung peninsula to be internationalized, not leased by the Soviet Union and for the Manchurian railroads to be run jointly by a Sino-Soviet commission instead of being owned by the Soviet Union.[48] Molotov agreed to Harriman's amendments, but when Churchill expressed his approval of Stalin's request for the Soviets to have a naval base at Port Arthur, the latter told Harriman that internationalization would not be possible for Port Arthur.[49] The final draft called for the internationalization of Dairen with a leading role reserved for the Soviet Union; the Soviets to have a naval base at Port Arthur; a Sino-Soviet commission to run the railroads of Manchuria; and China to recognize Outer Mongolia.[50]

On 10 February 1944, Harriman informed Stalin that Roosevelt had agreed to the British call for the "Big Four" to become the "Big Five" by including France in.[51] Specifically, the Americans were backing on the British call to recognize France as one of the great powers of the post-war world and to allow the French to have an occupation zone in Germany.[51] Through Stalin had been opposed to de Gaulle's claims for the French to have an occupation zone in Germany, the Anglo-American front on this issue, which was relatively unimportant to him, led him to tell Harriman that now agreed on a four-power occupation of Germany.[52] On 11 February 1945, the conference ended and Harriman went with Roosevelt on a drive in his Packard limousine through the Crimea, at the time a war devastated peninsula almost devoid of human life.[53] On 12 February 1945, Harriman saw Roosevelt, his friend since childhood, for the last time, as he boarded a C-54 airplane at Saki airfield to take him to Egypt.[54] Roosevelt had decided to go to Egypt to meet King Farouk of Egypt, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia in an effort to find a solution to the "Palestine Question" as the Jewish-Arab dispute was then known, which he feared would be a problem in the post-war world.[54] On 12 April 1945, Roosevelt died.

At the Yalta conference, it was agreed that American prisoners captured by the Germans and liberated by the Soviets were to immediately repatriated to American forces.[55] The fact that the Soviets made many difficulties about fulfilling this promise such as not allowing American officers into Poland to contact American POWs there led to frequent clashes between Harriman and Molotov, and contributed much to Harriman's increasing negative feelings about the Soviet Union.[55] On 11 May 1945, Harriman reported in a cable to Washington that Stalin "feared a separate peace by ourselves with Japan" before the Soviet Union had moved its forces eastwards to take invade Manchuria.[56] After Roosevelt's death, he attended the final "Big Three" conference at Potsdam. Although the new president, Harry Truman, was receptive to Harriman's anti-Soviet hard line advice, the new secretary of state, James Byrnes, managed to sideline him. While in Berlin, he noted the tight security imposed by Soviet military authorities and the beginnings of a program of reparations by which the Soviets were stripping out German industry.[10]

In 1945, while Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Harriman was presented with a Trojan Horse gift. In 1952, the gift, a carved wood Great Seal of the United States, which had adorned "the ambassador's Moscow residential office" in Spaso House, was found to be bugged.[57][58][59]

Statesman of foreign and domestic affairs

Harriman served as ambassador to the Soviet Union until January 1946. When he returned to the United States, he worked hard to get George Kennan's Long Telegram into wide distribution.[10] Kennan's analysis, which generally lined up with Harriman's, became the cornerstone of Truman's Cold War strategy of containment.

From April to October 1946, he was ambassador to Britain, but he was soon appointed to become United States Secretary of Commerce under President Harry S. Truman to replace Henry A. Wallace, a critic of Truman's foreign policies. In 1948, he was put in charge of the Marshall Plan. In Paris, he became friendly with the CIA agent Irving Brown, who organised anti-communist unions and organisations.[60][61] Harriman was then sent to Tehran in July 1951 to mediate between Iran and Britain in the wake of the Iranian nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.[62]

In the 1954 race to succeed Republican Thomas E. Dewey as Governor of New York, the Democratic Harriman defeated Dewey's protege, U.S. Senator Irving M. Ives, by a tiny margin. He served as governor for one term until Republican Nelson Rockefeller unseated him in 1958. As governor, he increased personal taxes by 11% but his tenure was dominated by his presidential ambitions. Harriman was a candidate for the Democratic Presidential Nomination in 1952, and again in 1956 when he was endorsed by Truman but lost (both times) to Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson.

Despite the failure of his presidential ambitions, Harriman became a widely respected elder statesman of the party. In January 1961, he was appointed Ambassador at Large in the Kennedy administration, a position he held until November, when he became Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs. In 1961, at the suggestion of Ambassador Charles W. Yost Harriman represented President Kennedy at the funeral of King Mohammed V of Morocco. During this period he advocated U.S. support of a neutral government in Laos and helped to negotiate the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963.

Accusation of spying for the Soviet Union

In December 1961, Anatoliy Golitsyn defected from the Soviet Union and accused Harriman of being a Soviet spy, but his claims were dismissed by the CIA and Harriman remained in his position until April 1963, when he became Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs. He retained that position during the transition to the Johnson administration until March 1965 when he again became Ambassador at Large. He held that position for the remainder of Johnson's presidency. Harriman headed the U.S. delegation to the preliminary peace talks in Paris between the United States and North Vietnam (1968–69).

Vietnamese coup d'état

President-elect Kennedy appointed Harriman as ambassador-at-large, to operate "with the full confidence of the president and an intimate knowledge of all aspects of United States policy." But by 1963, Kennedy had come to suspect the loyalty of certain members on his national security team. According to Colonel William Corson, USMC, by 1963 Harriman was running "Vietnam without consulting the president or the attorney general."[63] Corson said Kenny O'Donnell, JFK's appointments secretary, was convinced that the National Security Advisor, McGeorge Bundy, followed the orders of Harriman rather than the president. Corson also claimed that O'Donnell was particularly concerned about Michael Forrestal, a young White House staffer who handled liaison on Vietnam with Harriman.[63]

Harriman certainly supported the coup against the South Vietnam president Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963. However, it is alleged that the orders that ended in the deaths of Diem and his brother actually originated with Harriman and were carried out by Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.'s military assistant.[64][65] The fundamental question about the murders was the sudden and unusual recall of Saigon Station Chief John "Jocko" Richardson by an unknown authority. Special Operations Army officer, John Michael Dunn, was sent to Vietnam in his stead. He followed the orders of Harriman and Forrestal rather than the CIA.[63] According to Corson, Dunn's role in the incident has never been made public but he was assigned to Ambassador Lodge for "special operations" with the authority to act without hindrance; and he was known to have access to the coup plotters. Corson speculated that with Richardson recalled the way was clear for Dunn to freely act.[63]

Later years

On 15 October 1969, Harriman was a featured speaker at the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam protest march in New York.[66] In his speech, Harriman denounced the Vietnam war as immoral and stated that President Richard Nixon "is going to have pay attention."[66]

Harriman received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, with Distinction, in 1969 and West Point's Sylvanus Thayer Award in 1975. Furthermore, in 1983 he received the Freedom Medal.

In 1973 he was interviewed in the now famous TV documentary series, The World at War, where he gives a recollection of his experiences as Roosevelt's personal representative in Britain along with his views on Cold War politics; in particular Poland and the Warsaw Pact; along with the exchanges he witnessed between Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin. In one such recollection he describes Stalin as utterly cruel.[67]

Harriman was appointed senior member of the US Delegation to the United Nations General Assembly's Special Session on Disarmament in 1978. He was also a member of the American Academy of Diplomacy Charter, Club of Rome, Council on Foreign Relations, Knights of Pythias, Skull and Bones society, Psi Upsilon fraternity, and the Jupiter Island club.

Personal life

Harriman's first marriage, two years after graduating from Yale, was to Kitty Lanier Lawrence.[68] Lawrence was the great-granddaughter of James Lanier, a co-founder of Winslow, Lanier & Co., and the granddaughter of Charles D. Lanier (1837–1926), a close friend of J.P. Morgan[69] Before their divorce in 1929, and her death in 1936, Harriman and Lawrence had two daughters together: [70]

- Mary Averell Harriman (1917–1996), who married Shirley C. Fisk[71]

- Kathleen Lanier Harriman (1917–2011), who married Stanley Grafton Mortimer Jr. (1913–1999),[72] who had previously been married to socialite Babe Paley (1915–1978)[73]

About a year after his divorce from Lawrence, Harriman married Marie Norton Whitney (1903–1970), who had left her husband, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, to marry him. On their honeymoon in Europe, they purchased oil paintings by Van Gogh, Degas, Cézanne, Picasso, and Renoir.[74] She and her husband later donated many of the works she bought and collected, including those of the artist Walt Kuhn, to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[75] They remained married until her death on September 26, 1970, at George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C.[76]

In 1971, he married for the final time to Pamela Beryl Digby Churchill Hayward (1920–1997), the former wife of Winston Churchill's son Randolph, and widow of Broadway producer Leland Hayward. Harriman and Pamela Churchill had had an affair during the War in 1941 which led to the breakdown of her marriage to Randolph Churchill. In 1993, she became the 58th United States Ambassador to France.[77]

Harriman died on July 26, 1986 in Yorktown Heights, New York, at the age of 94. Averell and Pamela Harriman are buried at the Arden Farm Graveyard in Arden, New York.

Legacy and honors

- The Harriman Hall at Stony Brook University was named in his honor.

- The W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus in Albany, New York, also carries his name.

- Harriman State Park (Idaho)

For the state park in New York named after his parents, see Harriman State Park (New York). Harriman State Park is a state park in eastern Idaho, United States. It is located on an 11,000-acre (45 km2) wildlife refuge in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and is home to an abundance of elk, moose, sandhill cranes, trumpeter swans, and the occasional black or grizzly bear. Two-thirds of the trumpeter swans that winter in the contiguous United States spend the season in Harriman State Park. The land was deeded to Idaho for free in 1977 by Roland and W. Averell Harriman, whose insistence that the state have a professional park managing service helped prompt the creation of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation in 1965. The park opened to the public in 1982. It is located in Fremont County, 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Island Park, Idaho. Henry's Fork, a fly-fishing stream, winds through the meadows of Harriman State Park. In winter, many of its roads and trails are groomed for cross country skiing.

Summary of career

- Vice President, Union Pacific Railroad Co., 1915–17

- Director, Illinois Central Railroad Co., 1915–46

- Member, Palisades Interstate Park Commission, 1915–54

- Chairman, Merchant Shipbuilding Corp.,1917–25

- Chairman, W. A. Harriman & Company, 1920–31

- Partner, Soviet Georgian Manganese Concessions, 1925–28

- Chairman, executive committee, Illinois Central Railroad, 1931–42

- Senior partner, Brown Brothers Harriman & Co., 1931–46

- Chairman, Union Pacific Railroad, 1932–46

- Co-founder, Today magazine with Vincent Astor, 1935–37 (merged with Newsweek in 1937)

- Administrator and Special Assistant, National Recovery Administration, 1934–35

- Founder, Sun Valley Ski Resort, Idaho, 1936

- Chairman, Business Advisory Council, 1937–39

- Chief, Materials Branch & Production Division, Office of Production Management, 1941

- U.S. Ambassador & Special Representative to the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, 1941–43

- Chairman, Ambassador & Special Representative of the U.S. President's Special Mission to the USSR, 1941–43

- U.S. Ambassador to the USSR, 1943–46

- U.S. Ambassador, Britain, 1946

- U.S. Secretary of Commerce, 1946–48

- United States Coordinator, European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan), 1948–50

- Special Assistant to the U.S. President, 1950–52

- U.S. Representative and Chairman, North Atlantic Commission on Defense Plans, 1951–52

- Director, Mutual Security Agency, 1951–53

- Candidate, Democratic nomination for U.S. President, 1952

- Governor, State of New York, 1955–59

- Candidate, Democratic nomination for U.S. President, 1956

- U.S. Ambassador-at-large, 1961

- United States Deputy Representative, International Conference on the Settlement of the Laotian, 1961–62

- Assistant US Secretary of State, Far Eastern Affairs, 1961–63

- Special Representative to the U.S. President, Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, 1963

- Under Secretary of State, Political Affairs, 1963–65

- U.S. Ambassador-at-large, 1965–69

- Chairman, President's Commission of the Observance of Human Rights Year, 1968

- Personal Representative of the U.S. President, Peace Talks with North Vietnam, 1968–69

- Chairman, Foreign Policy Task Force, Democratic National Committee, 1976

Publications

- "Leadership in World Affairs." Foreign Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 4, July 1954, pp. 525–540. doi:10.2307/20031052

See also

- Florence Jaffray Harriman

- U.S. presidential election, 1952

- U.S. presidential election, 1956

References

- Robbins, Alexandra (2002). Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-72091-7.

- The Business Council, Official website, Background Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Feustel Resigns as Trainer For the Log Cabin Stable". The New York Times. July 15, 1926. p. 19.

- Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917

- Theodore A. Wilson, The First Summit: Roosevelt and Churchill at Placentia Bay, 1941 (1991).

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 288.

- Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pg. 299-333 from The International History Review, Volume 33, No. 2 June 2011 p.308-309

- Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pg. 299-333 from The International History Review, Volume 33, No. 2 June 2011 p.308

- Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pg. 299-333 from The International History Review, Volume 33, No. 2 June 2011 p.309

- Cathal J. Nolan, Notable U.S. ambassadors since 1775: a biographical dictionary, 137-143.

- "An Evening with Averell Harriman" pg. 2-18 from Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 25, No. 4, January 1972 p. 4

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 135.

- Flynn, John. The Final Secret of Pearl Harbor (October 1945)

- Kennedy, David Freedom From Fear p.486-487.

- Kennedy, David Freedom From Fear p.627-628.

- Kennedy, David Freedom From Fear p.630-631.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 157.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 198.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 199.

- Kennedy, David Freedom From Fear p.675.

- Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pg. 299-333 from The International History Review, Volume 33, No. 2 June 2011 p.315-316

- Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pg. 299-333 from The International History Review, Volume 33, No. 2 June 2011 p.316

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 620.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 620-621.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 621.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 623.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 624.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 236.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 200.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 244-245.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 247

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 87.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 95.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 96.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 46.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 287.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 88.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 88-89.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 89.

- Rees, Laurence World War II Behind Closed Doors p. 331.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 833.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 7.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 6-7.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 96

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 96-97.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 97.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 97-98

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 98.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 98-99.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 99.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 29.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 30.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 119.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 119-120.

- Weinberg, Gerhard A World At Arms p. 808.

- Buhite, Russell Decisions at Yalta p. 102.

- "National Cryptologic Museum Exhibit Information". nsa.gov. National Cryptologic Museum. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Cold War: Great Seal ; On August 4, 1945, Soviet school children gave a carving of the Great Seal of the United States to U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman. It hung in the ambassador's Moscow residential office until 1952 when the State Department discovered that it was 'bugged.' The microphone hidden inside was passive and only activated when the Soviets wanted it to be. They shot radio waves from a van parked outside into the ambassador's office and could then detect the changes of the microphone's diaphragm inside the resonant cavity. When Soviets turned off the radio waves it was virtually impossible to detect the hidden 'bug.' The Soviets were able to eavesdrop on the U.S. ambassador's conversations for six years. The replica on display in the Museum was molded from the original after it came to NSA for testing. The exhibit can be opened to reveal a copy of the microphone and the resonant cavity inside.

- "Cold War: Great Seal Exhibit". nsa.gov. National Cryptologic Museum. VIRIN: 190530-D-IM742-4006.JPG. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- "Congressional Record - 101st Congress (1989-1990) - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Archived from the original on 24 February 1999.

HON. HENRY J. HYDE:... `Quivering with excitement, the technician extracted from the shattered depths of the seal a small device, not much larger than a pencil . . . capable of being activated by some sort of electronic ray from outside the building. When not activated, it was almost impossible to detect. . . . It represented, for that day, a fantastically advanced bit of applied electronics.' In displaying this equipment to the United Nations, Henry Cabot Lodge charged that more than 100 similar devices had been recovered in U.S. missions and residences in the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe.

(INTRODUCTION TO 'EMBASSY MOSCOW: ATTITUDES AND ERRORS' – (BY HENRY J. HYDE, REPUBLICAN OF ILLINOIS) (Extension of Remarks - October 26, 1988) page [E3490]) - Harry Kelber, "AFL-CIO's Dark Past", 22 November 2004, on laboreducator.org

- Frédéric Charpier, La CIA en France. 60 ans d'ingérence dans les affaires françaises, Seuil, 2008, p. 40–43. See also Les belles aventures de la CIA en France Archived 2007-04-20 at Archive.today, 8 January 2008, Bakchich.

- Azimi, Fakhreddin. "Iranica.com - HARRIMAN MISSION". bibliothecapersica.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2005.

- "The Secret History of the CIA." Joseph Trento. 2001, Prima Publishing. pp. 334–335.

- "Presidential Recordings Program". whitehousetapes.org.

- "Presidential Recordings Program". whitehousetapes.org.

- Karnow, Stanley Vietnam: A History p. 599.

- "Pincers (August 1944 – March 1945)". The World at War. Episode 19. 20 March 1974. 21 minutes in. ITV.

Stalin was very suspicious of the underground, but it was utterly cruel that he wouldn't even try to get supplies in. He refused to let our aeroplanes fly and try to drop supplies for several weeks. And that was a shock to all of us. I think it played a role in all our minds as to the heartlessness of the Russians. Averell Harriman U.S. Ambassador to Russia 1943-46

- Staff (July 3, 1915). "MISS LAWRANCE TO WED W. A. HARRIMAN Romance in Match of Late Railroad Magnate's Son and C. Lanier's Granddaughter. FIANCEE A SPORTS DEVOTEE Just Recovered from Injury Received While Horseback Riding with the Young Financier". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Vincent P. Carosso, Rose C. Carosso, "The Morgans" (Harvard University Press, 1987) p. 248

- "W.A. Harriman Wed to Mrs. C.V. Whitney" (PDF). New York Times. February 22, 1930. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- Saxon, Wolfgang (January 10, 1996). "Mary A. Fisk, 78, an Advocate Of Tutoring in Primary Grades". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Fox, Margalit (February 19, 2011). "Kathleen Mortimer, Rich and Adventurous, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Nemy, Enid (July 7, 1978). "Barbara Cushing Paley Dies at 63; Style Pace-Setter in Three Decades; Symbol of Taste". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

Barbara Cushing Paley, the wife of William S. Paley, the chairman of the board of the Columbia Broadcasting System, died of cancer at their apartment in New York City yesterday after a long illness. She was 63 years old.

- Isaacson, Walter; Thomas, Evan (1986). The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made. Simon & Schuster. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-684-83771-0.

- "The Marie and Averell Harriman Collection". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- "Mrs. W. Averell Harriman Dies; Former Governor's Wife Was 67". New York Times. September 27, 1970. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- Berger, Marilyn (6 February 1997). "Pamela Harriman Is Dead at 76; An Ardent Political Personality". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Abramson, Rudy (1992). Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0688043520.

- Bland, Larry I. "Averell Harriman, the Russians and the Origins of the Cold War in Europe, 1943–45." Australian Journal of Politics and History 1977 23(3): 403-416. ISSN 0004-9522

- Chandler, Harriette L. "The Transition to Cold Warrior: the Evolution of W. Averell Harriman's Assessment of the U.S.S.R.'s Polish Policy, October 1943 Warsaw Uprising." East European Quarterly 1976 10(2): 229-245. ISSN 0012-8449.

- Clemens, Diane S. "Averell Harriman, John Deane, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the 'Reversal of Co-operation' with the Soviet Union in April 1945." International History Review 1992 14(2): 277-306. ISSN 0707-5332.

- Isaacson, Walter; Thomas, Evan. The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made: Acheson, Bohlen, Harriman, Kennan, Lovett, McCloy. Simon & Schuster, 1986. ISBN 978-0671504656.

- Langer, John Daniel. "The Harriman-beaverbrook Mission and the Debate over Unconditional Aid for the Soviet Union, 1941." Journal of Contemporary History 1979 14(3): 463-482. ISSN 0022-0094.

- Larsh, William. "W. Averell Harriman and the Polish Question, December 1943-August 1944." East European Politics and Societies 1993 7(3): 513-554. ISSN 0888-3254.

- Moynihan, Daniel Patrick; Wilson, James Q. "Patronage in New York State, 1955–1959." American Political Science Review 1964 58(2): 286-301. ISSN 0003-0554.

- Olson, Lynne (2010). Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood with Britain in Its Darkest, Finest Hour. Random House. ISBN 978-1400067589.

- Paterson, Thomas G. "The Abortive American Loan to Russia and the Origins of the Cold War, 1943–1946." Journal of American History 1969 56(1): 70-92. ISSN 0021-8723.

- Soares, John. "Averell Harriman Has Changed His Mind: The Seattle Speech and the Rhetoric of Cold War Confrontation". Cold War History, 9 (May 2009), 267–86.

- Wehrle, Edmund F. "'A Good, Bad Deal': John F. Kennedy, W. Averell Harriman, and the Neutralization of Laos, 1961–1962." Pacific Historical Review, 1998 67(3): 349-377. ISSN 0030-8684.

Primary sources

- W. Averell Harriman. America and Russia in a changing world: A half century of personal observation (1971)

- W. Averell Harriman. Public papers of Averell Harriman, fifty-second governor of the state of New York, 1955–1959 (1960)

- Harriman, W. Averell and Abel, Elie. Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin, 1941–1946. (1975). 595 pp.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: W. Averell Harriman |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to W. Averell Harriman. |

- Papers of W. Averell Harriman at the Library of Congress

- W. Averell Harriman has been interviewed as part of Frontline Diplomacy: The Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, a site at the Library of Congress.

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Averell W. Harriman" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Averell Harriman (May 30, 1952)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Averell Harriman (October 29, 1952)" is available at the Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about W. Averell Harriman in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Standley |

United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union 1943–1946 |

Succeeded by Walter Bedell Smith |

| Preceded by John Winant |

United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom 1946 |

Succeeded by Lewis Douglas |

| New office | Director of the Mutual Security Agency 1951–1953 |

Succeeded by Harold Stassen |

| Preceded by Walter P. McConaughy |

Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs 1961–1963 |

Succeeded by Roger Hilsman |

| Preceded by George C. McGhee |

Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs 1963–1965 |

Succeeded by Eugene V. Rostow |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Henry A. Wallace |

United States Secretary of Commerce 1946–1948 |

Succeeded by Charles Sawyer |

| Preceded by Thomas E. Dewey |

Governor of New York 1955–1958 |

Succeeded by Nelson Rockefeller |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Walter A. Lynch |

Democratic nominee for Governor of New York 1954, 1958 |

Succeeded by Robert M. Morgenthau |

| Awards | ||

| Preceded by Robert Daniel Murphy |

Recipient of the Sylvanus Thayer Award 1975 |

Succeeded by Gordon Gray |