Ngô Đình Thục

Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục (Vietnamese pronunciation: [ŋo ɗîŋ̟ tʰùkp]) (6 October 1897 – 13 December 1984) was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Huế, Vietnam, and was later a sedevacantist bishop. He was a member of the Ngô family who ruled South Vietnam in the years leading up to the Vietnam War. He was the founder of Dalat University.

His Excellency Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Huế | |

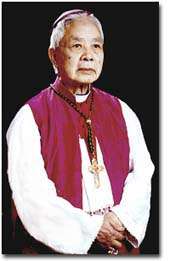

Portrait of Ngo Dinh Thuc. | |

| Native name | Phêrô Máctinô Ngô Đình Thục |

| See | Archdiocese of Huế |

| Installed | 24 November 1960 |

| Term ended | 17 February 1968 |

| Predecessor | Jean-Baptiste Urrutia, Vicar Apostolic of Huế |

| Successor | Philippe Nguyên-Kim-Diên |

| Other posts |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 20 December 1925 |

| Consecration | 4 May 1938 by Antonin-Fernand Drapier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 6, 1897 Huế, French Indochina |

| Died | December 13, 1984 (aged 87) Carthage, Missouri |

| Buried | Springfield, Missouri |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents | Ngô Đình Khả |

| Education | Philosophy, Theology, Canon law |

| Alma mater | Pontifical Gregorian University |

| Motto | Miles Christi (Soldier of Christ) |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

Ordination history of Ngô Đình Thục | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While Thục was in Rome attending the second session of the Second Vatican Council, the 1963 South Vietnamese coup overthrew and assassinated his younger brother Ngô Đình Diệm, who was president of South Vietnam. Thục was unable to return to Vietnam and lived the rest of his life exiled in Italy, France, and the United States. During his exile, he was involved with Traditionalist Catholic movements and consecrated a number of bishops without the Vatican's approval for the Palmarian and Sedevacantist movements. As a result, he was excommunicated by the Holy See and later reconciled with the Vatican a number of times.

Family

Ngô Đình Thục was born in Huế to an affluent Roman Catholic family as the second of the six surviving sons born to Ngô Đình Khả, a mandarin of the Nguyễn dynasty who served Emperor Thành Thái during the French occupation of Vietnam.

Thục's elder brother, Khôi, served as a governor and mandarin of the French-controlled Emperor Bảo Đại's administration. At the end of World War Two, both Khôi and Thục's younger brother Diệm were arrested for having collaborated with the Japanese.[1] Diệm was released, but Khôi was subsequently shot by the Việt Minh as part of the August Revolution of 1945 (and not buried alive as is sometimes stated).[2] All of Thục's brothers, including Diệm, Nhu and Cẩn, were politically active. Diệm had been Interior Minister under Bảo Đại in the 1930s for a brief period, and sought power in the late 1940s and 1950s under a Catholic anti-communist platform as various groups tried to establish their rule over Vietnam. After being appointed Prime Minister, Diệm used a rigged referendum to remove Bao Dai and declare himself president of South Vietnam in 1955. Diệm, Nhu and Cẩn were all later assassinated during and shortly after the 1963 South Vietnamese coup.

Cardinal François Xavier Nguyễn Văn Thuận (1928–2002) was Thục's nephew.

Career in Vietnam

At age twelve, Thục entered the minor seminary in An Ninh. He spent eight years there before going on to study philosophy at the major seminary in Huế. Following his ordination as a priest on 20 December 1925, he was selected to study theology in Rome, and is often said to have earned three doctorates from the Pontifical Gregorian University in philosophy, theology, and Canon law; this is not substantiated by the university's archives however.[3] He briefly lectured at the Sorbonne and gained teaching qualifications before returning to Vietnam in 1927.[3] He then became a professor at the College of Vietnamese Brothers in Huế, a professor at the major seminary in Huế, and Dean of the College of Providence. In 1938, he was chosen by Rome to direct the Apostolic Vicariate at Vĩnh Long. He was consecrated a bishop on 4 May 1938, being the third Vietnamese priest raised to the rank of bishop.

In 1950 Diệm and Thục applied for permission to travel to Rome for the Holy Year celebrations at the Vatican but went instead to Japan to lobby Prince Cường Để to enlist support to seize power. They met Wesley Fishel, an American academic consultant for the U.S. government. Fishel was a proponent of the anti-colonial, anti-communist third force doctrine in Asia and was impressed by Diệm. He helped the brothers organise contacts and meetings in the United States to enlist support.[4]

With the outbreak of the Korean War and McCarthyism in the early 1950s, Vietnamese anti-communists were a sought-after commodity in the United States. Diệm and Thục were given a reception at the State Department with the Acting Secretary of State James Webb, where Thục did much of the talking. Diệm and Thục also forged links with Cardinal Francis Spellman, the most politically influential cleric of his time, and Spellman became one of Diệm's most powerful advocates. Diệm then managed an audience with Pope Pius XII in Rome with his brother's help, and then settled in the US as a guest of the Maryknoll Fathers.[5] Spellman helped Diệm to garner support among right-wing and Catholic circles. Thục was widely seen as more genial, loquacious, and diplomatic than his brother, and it was acknowledged that Thục would be highly influential in the future regime.[6] As French power in Vietnam declined, Diệm’s support in America, which Thục helped to nurture, made his stock rise. Bảo Đại made Diệm the Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam because he thought Diệm's connections would secure foreign financial aid.[7]

Diệm's rule

In October 1955, Diệm deposed Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum organised by Nhu and declared himself President of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam, which then concentrated power in the Ngô family, who were dedicated Roman Catholics in a Buddhist majority country.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Power was enforced through secret police and the imprisonment and torture of political and religious opponents. The Ngôs' policies and conduct inflamed religious tensions. The government was biased towards Catholics in public service and military promotions, as well as the allocation of land, business favors and tax concessions.[15] Thuc, the most powerful religious leader in the country, was allowed to solicit "voluntary contributions to the Church" from Saigon businessmen, which was likened to "tax notices".[16] Thuc also used his position to acquire farms, businesses, urban real estate, rental property and rubber plantations for the Catholic Church. He also used Army of the Republic of Vietnam personnel to work on his timber and construction projects.[17]

Buddhist unrest and downfall of Diệm

In May 1963, in the central city of Huế, where Thục was archbishop, Buddhists were prohibited from displaying the Buddhist flag during Vesak celebrations commemorating the birth of Gautama Buddha, when the government cited a regulation prohibiting the display of non-government flags at Thục's request.[18] A few days earlier, Catholics were encouraged to fly Vatican flags to celebrate Thục's 25th anniversary as bishop. Government funds were used to pay for Thục's anniversary celebrations, and the residents of Huế—a Buddhist stronghold—were also forced to contribute. These perceived double standards led to a Buddhist protest against the government, which was ended when nine civilians were shot dead or run over when the military attacked. Despite footage showing otherwise, the Ngôs blamed the Việt Cộng for the deaths,[19][20] and protests for equality broke out across the country. Major Dang Sy, the commanding officer in the incident, later revealed that Archbishop Thục had personally given him the order to open fire.[21] Thục called for his brothers to forcefully suppress the protesters. Later, the Ngôs' forces attacked and vandalised Buddhist pagodas across the country in an attempt to crush the burgeoning movement. It is estimated that up to 400 people were killed or disappeared.[22]

Diệm was overthrown and assassinated together with Nhu on 2 November 1963. Ngô Đình Cẩn was sentenced to death and executed in 1964. Of the six brothers, only Thục and Luyện survived the political upheavals in Vietnam. Luyện, the youngest, was serving as ambassador in London, and Thục had been summoned to Rome for the Second Vatican Council. Because of the coup, Thục remained in Rome during the Council years (1962–65), and after the Council, none of the relevant governments - America, Vietnam or The Vatican consented to him returning to Vietnam.[23] To evade punishment by the post-Diệm government, Archbishop Thục was not allowed to return to his duties at home and thus began his life in exile, initially in Rome.[24]

Exile

Apparently becoming convinced of a crisis devastating the Roman Catholic Church, and coming under the increasing influence of sedevacantist Catholics, Thục consecrated several bishops without a mandate from the Holy See.[25] In December 1975 he went to Palmar de Troya, where he ordained Clemente Domínguez y Gómez — who claimed to have repeatedly witnessed apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary — and others, and the following month he consecrated Dominguez and four of the Palmar sect as bishops.[26] Thục stated that he had gone to Palmar de Troya on the spur of the moment, though contemporary sources show him to have been a regular visitor since 1968.[27]

Thục moved to Toulon, France, where he was assigned a confessional in the cathedral until about 1981. He at least once concelebrated the Mass of Paul VI (the new rite of Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969) in the vernacular. According to one sedevacantist journal, Thục served at the Mass of Paul VI as an acolyte several times.[28] Shortly after his arrival he consecrated Jean Laborie as an independent bishop, even though Laborie had been consecrated twice previously.

In May 1981 Thục consecrated a French priest, Michel-Louis Guérard des Lauriers, as bishop.[26] Des Lauriers was a Dominican, an expert on the dogma of the Assumption and advisor to Pope Pius XII,[29] and former professor at the Pontifical Lateran University. In October 1981, he consecrated two Mexican priests and former seminary professors, Moisés Carmona (of Acapulco) and Adolfo Zamora (of Mexico City).[30] Both of these priests were convinced that the Papal See of Rome was vacant and the successors of Pope Pius XII were heretical usurpers of papal office and power. In February 1982, in Munich's Sankt Michael church, Thục issued a declaration that the Holy See in Rome was vacant, intimating that he desired a restoration of the hierarchy to end the vacancy. However, his newly consecrated bishops became a fragmented group. Many limited themselves essentially to sacramental ministry and only consecrated a few other bishops.[31]

Thục may have performed other consecrations besides the five bishops at Palmar de Troya and the three sedevacantists in 1981. He is said to have consecrated two priests, Luigi Boni and Jean Gerard Roux, in Loano in Italy on 18 April 1982, but a Dr. Heller, of Una Voce in Munich, has said that Thục was with him in Munich on that date.[32] The bishops consecrated by Thục proceeded to consecrate other bishops for various Catholic splinter groups, many of them sedevacantists.

Thục departed for the United States in 1983 at the invitation of Bishop Louis Vezelis, a Franciscan former missionary priest who had agreed to receive episcopal consecration by the Thục line Bishop George J. Musey, assisted by co-consecrators, Bishops Carmona, Zamora and Martínez, in order to provide bishops for an "imperfect council" which was to take place later in Mexico in order to elect a legitimate Pope from among themselves. Thục began to be increasingly sought-out by the expatriate and refugee Vietnamese community, including old friends and contacts from Huế and Saigon.[33] They facilitated his extraction from the sedevacantist world and, after two formal excommunications in 1975 and 1983, Thục returned to the jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in 1976 and definitively in 1984.[34][35] Thục died at the monastery of the Vietnamese American religious Congregation of the Mother Co-Redemptrix on 13 December 1984, at Carthage, Missouri, aged 87.

See also

- Roman Catholicism in Vietnam

References

- Jarvis, pp. 39-40

- Jarvis, p. 40

- Jarvis, p. 27

- "University Project Cloaked C.I.A. Role In Saigon, 1955–59", New York Times, 14 April 1966

- "The Beleaguered Man", Time, 4 April 1955; accessed 27 March 2008. "For the best part of two years (1951–53) he made his home at the Maryknoll Junior Seminary in Lakewood, N.J.. often going down to Washington to buttonhole State Department men and Congressmen and urge them not to support French colonialism."

- Jarvis, pp. 41-42

- Jacobs, pp. 25–34

- The 1966 Buddhist Crisis in South Vietnam Archived 2008-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, HistoryNet

- Gettleman, pp. 275–76, 366

- Moyar, pp. 215–16

- "South Viet Nam: The Religious Crisis". Time. 14 June 1963. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Tucker, pp. 49, 291, 293.

- Maclear, p. 63.

- SNIE 53-2-63, "The Situation in South Vietnam", 10 July 1963

- Tucker, p. 291

- Jacobs, p. 89.

- Olson, p. 98.

- Topmiller, p. 2

- Karnow, p. 295

- Moyar, pp. 212–13

- Hammer, pp. 114–16.

- Gettleman, pp. 64–83

- Jarvis, pp. 72-73

- Jarvis, p. 73

- Uhlenbrock, Robert W. "Abp. Thuc: A Brief Defense | Articles: Thuc, Abp. | Traditional Latin Mass Resources". www.traditionalmass.org. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Michael W. Cuneo, The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism, JHU Press, 1999,p. 99.

- Jarvis, p. 83

- Rev. Fr. Noël Barbara, Fortes in fide, Nr 12.

- M.L. Guérard des Lauriers, Dimensions de la Foi, Paris: Cerf, 1952

- Griff Ruby, The Resurrection of the Roman Catholic Church: A Guide to the Traditional Catholic Movement, iUniverse, 2002, pp. 138–9.

- "Misericordias Domini in æternum cantabo": Autobiography by Mgr. Ngô Đình Thục, written ca. 1978–1980. Einsicht – röm.-kath. Zeitschrift: Munich

- Schmitt, Oskar (2006). Ein würdiger Verwalter im Weinberg unseres Herrn Jesus Christus: Bischof Pierre Martin Ngô-dinh-Thuc (in German). Books on Demand. pp. 134–5. ISBN 9783833453854. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Jarvis, p. 120-121

- Jarvis, p. 121-123

- catholic-hierarchy.org

Further reading

- Borthwick, Mark (1998). Pacific Century: The Emergence of Modern Pacific Asia. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3471-3.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967). Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled. Praeger Publishers.

- Fall, Bernard B. (1963). The Two Viet-Nams. Praeger Publishers.

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1966). Vietnam: History, Documents, and Opinions on a Major World Crisis. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books.

- Halberstam, David; Singal, Daniel J. (2008). The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-6007-4.

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1987). A Death in November: America in Vietnam, 1963. New York City: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24210-4.

- Jacobs, Seth (2004). America's miracle man in Vietnam: Ngo Dinh Diem, religion, race, and U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia, 1950–1957. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3440-2.

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8.

- Jarvis, Edward (2018). Sede Vacante: The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Thuc. Berkeley, California: Apocryphile Press. ISBN 1-949643-02-6.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: how the assassinations of Diem and JFK prolonged the Vietnam War. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505286-2.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam: the war, 1954–1975. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

- Luz, Frédéric (1995). Le Soufre et l'Encens: enquête sur les eglises parallèles et les évêques dissidents. Claire Vigne. ISBN 9782841930210.

- Maclear, Michael (1981). Vietnam:The Ten Thousand Day War. New York City: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 0-423-00580-4.

- Moyar, Mark (2006). Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86911-0.

- Olson, James S. (1996). Where the Domino Fell. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08431-5.

- Sheehan, Neil (1989). A Bright Shining Lie. New York City: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-72414-8.

- Topmiller, Robert J. (2006). The Lotus Unleashed: The Buddhist Peace Movement in South Vietnam. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2260-0.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-040-9.

- Warner, Denis (1964). The Last Confucian: Vietnam, South-East Asia, and the West. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

External links

- Roman Catholic Hierarchy: Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục

- Episcopal lineages derived from Archbishop Ngo Dhin Thuc

- In Memoriam: Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục at the Wayback Machine (archived March 5, 2008) by Michel-Louis Guérard des Lauriers, O.P.

- Sedevacantist Declaration of Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục

- PDF Document of Einsicht, 1982; includes photographic documentation on many of Archbishop Thục's consecrations

- "The validity of the Thục consecrations" by Fr. Anthony Cekada in Sacerdotium, Spring 1992.

- A critical analysis of the invalidity of Bishop Thục's ordinations and consecrations

- Fr. Stepanich O.F.M. on the Thục-line consecrations

- Thucbishops.com – An online resource including theological treatises on the sedevacantist consecrations of bishops by Archbishop Thục.

- Thuc Admitted He Withheld his Sacramental Intention 10 Times