Volga–Don Canal

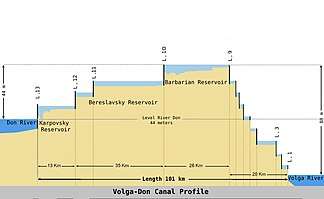

Lenin Volga–Don Shipping Canal (Russian:Волго-Донской судоходный канал имени, В. И. Ленина, Volga-Donskoy soudokhodniy kanal imeni V. I. Lenina, abbreviated ВДСК, VDSK) is a canal that connects the Volga River and the Don River at their closest points. Opened in 1952, the length of the waterway is 101 km (63 mi), 45 km (28 mi) of which is through rivers and reservoirs.

| Volga–Don Canal | |

|---|---|

Volga–Don Canal in October 2009 | |

Volga–Don Canal map | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 63[1] miles (101 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 141 m (463 ft)[2] |

| Maximum boat beam | 16.8 m (55 ft)[2] |

| Maximum boat draft | 3.6 m (12 ft)[2] |

| Locks | 13[3] |

| Maximum height above sea level | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Status | Open |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1948 |

| Date of first use | 1 June 1952 |

| Date completed | 1952 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Volgograd, Russia |

| End point | Tsimlyansk Reservoir, near Volgodonsk, Russia |

| Beginning coordinates | 48.664591°N 43.7917066°E |

| Ending coordinates | 48.523552°N 44.551892°E |

The canal forms a part of the Unified Deep Water System of European Russia. Together with the lower Volga and the lower Don, the Volga–Don Canal provides the most direct navigable connection between the Caspian Sea and the world's oceans via the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea.

History

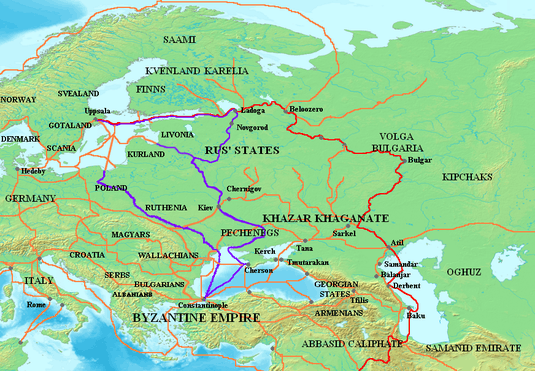

There has been a trade and military route between the Volga and Don rivers from early human history. The existence of Tanais in the Don River delta, which dates backs the Bosporan Kingdom in c. 438 BC – c. 370 AD, indicates that this route may have existed for more than two thousand years. The Sarkel fortress, located in the left bank of the lower Don River, controlled this Volga trade route.[4] Both Sarkel and Tanais were located on this trade route.

The Don–Volga Portage got its name from its trade importance 1000 years ago[5].

In 1569, the Ottoman Empire attempted to connect the Volga and Don rivers via a canal. The Ottomans wanted to create a maritime link to Central Asia (especially the cities of Bukhara, Khwarazm and Samarkand) to facilitate trade.[6] Together with a proposed Suez canal, the Volga-Don canal would also allow Central Asian Muslims to perform pilgrimage to Mecca.[6] According to most historians, the Ottomans managed to dig one-third of the canal,[7][8] before work was abandoned due to adverse weather.[9] Other historians argue that the Ottomans merely leveled the ground so they could haul ships between the two rivers.[10] In the end, the Ottomans retreated from the area and Russia promised to respect trade and pilgrimage routes to Central Asia.[6]

The first Russian attempts to connect the Volga and Don rivers were made by Peter the Great.[11] After capturing Azov in 1696, he decided to build a canal, but due to a lack of resources and other problems, this attempt was abandoned in 1701. He initiated a second attempt (the so-called Ivanovsky Canal at Yepifan) under the administration of Knyaz Matvey Gagarin, however this canal was too shallow, as it was located in the upper course of both the Don and Volga rivers and their tributaries; Ilovlya River (a left tributary of the Don) and Kamyshinka river (right tributary of the Volga).[12][13] Compared to the current Volga–Don Canal it was much shorter, with the distance between this two rivers being 4 kilometers (2.5 mi). Between 1702 and 1707, twenty-four locks were constructed, and in 1707, about 300 ships passed the canal under difficult navigation conditions. This canal was named Petrov Val, after the city Petrov Val, in honor of Peter the Great[14]. In 1709 due to financial difficulties caused by the Great Northern War, the project was halted.

In 1711, under the terms of the Treaty of the Pruth, Russia left Azov and Peter the Great lost all interest in the canal, which was abandoned and fell into ruin.[15][16] Over time, other projects for connecting the two rivers were proposed, but none were attempted. However, Dubovsko-Kachalinsky railway, which was horse-drawn railway and Volga–Don railway, which is now part of the South Eastern Railway were built in 1846 and 1852 respectively in order link the Volga and the Don at the shortest distance.[17] They were 68km and 73km long respectively.[18][19]

The construction of today's Volga–Don Canal, designed by Sergey Zhuk's Hydroproject Institute, began prior to the Second World War, which interrupted the process. Construction works continued from 1948 to 1952 and the canal was opened on June 1, 1952. The canal and its facilities were built by about 900,000 workers including some 100,000 German POWs and 100,000 gulag prisoners. A day spent at the construction yard was counted as three days in prison, which spurred the prisoners to work. Several convicts were even awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour upon their release.

Upon completion, the Volga–Don Canal became an important link in the Unified Deep Water Transportation System of the European part of the USSR.

Operation

The canal starts at the Sarepta backwater on the Volga River (south of Volgograd; Lock No. 1 and the gateway arch are at 48°31′10″N 44°33′10″E) and ends in the Tsimlyansk Reservoir of the Don River at the town of Kalach-na-Donu. The canal has nine one-chamber canal locks on the Volga slope that can raise ships 88 m (289 ft), and four canal locks of the same kind on the Don slope that can lower ships 44 m (144 ft). The overall dimensions of the canal locks are smaller than those on the Volga River, however they can pass ships of up to 5,000 tonnes cargo capacity. The smallest locks are 145 m (476 ft) long, 17 m (56 ft) wide, and 3.6 m (12 ft) deep. The maximum allowed vessel size is 141 m (463 ft) long, 16.8 m (55 ft) wide and 3.6 m (12 ft) deep (the Volgo–Don Max Class).[2]

The Volga–Don Canal is filled from the Don river, with three powerful pumping stations that maintain water levels. Water is also taken from the canal and used for irrigation.

Types of cargo transported from the Don region to the Volga region include coal from Donetsk, Ukraine as well as minerals, building materials, and grain. Cargo that get transported from the Volga to the Don includes lumber, pyrites, and petroleum products (carried mostly by Volgotanker boats). Tourist ships travel in both directions.

The Volga–Don Canal, together with the Tsimlyansky water-engineering system (chief architect Leonid Polyakov), form part of an architectural ensemble dedicated to the battles for Tsaritsyn during the Russian Civil War and for Stalingrad during the German-Soviet War. The Russian classical composer Sergei Prokofiev wrote the tone poem The Meeting of the Volga and the Don to celebrate its completion.

According to the Maritime Board (Morskaya Kollegiya) of the Russian government, 10.9 million tonnes of cargo were carried over the Volga–Don Canal in 2004.[20]

An alternate (not necessarily comparable) source claims 8.05 million tonnes of cargo was transported through the canal in total in 2006. Most of the cargo was moved from the east to the west. Namely, 7.20 million tonnes were transported through the canal from the Volga/Caspian basin to the Don/Sea of Azov/Black Sea basin, and only 0.85 million tonnes in the opposite direction. Just over half of all cargo was oil or oil products (4.14 million tonnes), predominantly shipped from the Caspian region.[21]

It was reported in 2007 that in the first 55 years of the canal's operations 450,000 vessels had passed through carrying 336 million tonnes of cargo. Recent cargo volume stood at 12 million tonnes a year.[22]

In 2016, the core of Belarusian nuclear power plant VVER-1200, which weighed 330 tonnes, was 13 meters high, and 4.5 meters in diameter, was transferred to its destination by exploiting Tsimlyansk Reservoir, the Volga-Don Canal, the Volga–Baltic Waterway, Volkhov River and special rail car.[23]

Stamp gallery

USSR stamp, 1953: Lock No. 13

USSR stamp, 1953: Lock No. 13 USSR stamp, 1951

USSR stamp, 1951 USSR stamp, 1952

USSR stamp, 1952 Russia Stamp 2008

Russia Stamp 2008 USSR collection

USSR collection Illustration of a lock on the Volga–Don Canal (1953) (47°33′5.84″N 42°08′10.26″E)

Illustration of a lock on the Volga–Don Canal (1953) (47°33′5.84″N 42°08′10.26″E)

Future Plans

In the 1980s, construction started on a second canal between the Volga and the Don. The new canal, dubbed Volga–Don 2 (Russian: Волго-Дон 2; 48°56′37″N 44°30′25″E) would start from the township of Yerzovka on the Volgograd Reservoir, north (upstream) of the Volga Dam, as opposed to the existing Volga–Don Canal that starts south (downstream) of the dam.[24] This canal would reduce the number of locks that ships coming from the Volgograd Reservoir, or from any other Volga or Kama port farther north, would have to traverse on their way to the Don. The project was abruptly cancelled on 1 August 1990 due to financial considerations, although by that time more than 40 percent of allocated funds had already been spent.[24][25][26] Since then most of the stone and metal in the abandoned canal and its locks has been looted.[27]

As of 2007–2008, Russian authorities are considering two options for increasing the throughput of navigable waterways between the Caspian basin and the Black Sea. One option, which reuses the name "Volga–Don 2", is to build a second parallel channel ("second thread") of the Volga–Don Canal, equipped with larger locks 300 metres (980 ft) long. This plan would allow for an increase in the canal's annual cargo throughput from 16.5 million tonnes to 30 million tonnes. The other option, which seems to have more support from Kazakhstan,[28] who would be either canal's major customer, is to build the so-called Eurasia Canal along a more southerly route in the Kuma–Manych Depression, some sections of which currently form part of the much shallower Manych Ship Canal. Although this option would require digging a longer canal than Volga–Don, and would be of less use to vessels coming from the Volga, it would provide a more direct connection between the Caspian and the Sea of Azov. The Eurasia Canal would also require fewer locks than the Volga–Don, as elevations in the Kuma–Manych Depression are lower than the Volga–Don area.[29]

See also

References

- Сроки работы шлюзов (Lock operation periods), from the site of the Russian Shipping Companies' Association (in Russian)

- Egorov, E. V.; I. A. Ilnytskyi; V. I. Tonyuk (2015). "Dimensional Line-up of River-sea Navigational Tankers". In Guedes Soares, Carlos; Roko Dejhalla, Dusko Pavletic (eds.). Towards Green Marine Technology and Transport. Boca Raton, Fla., US: CRC Press. p. 518. ISBN 9781315643496. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Volga-Don Canal - canal, Russia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Elhaik E(2020)Diverse genetic origins of medieval steppe nomad conquerors – a response to Mikheyev et al(2019).

- https://www.ca-c.org/c-g/2009/journal_eng/c-g-1/14.shtml

- Giancarlo Casale. The Ottoman Age of Exploration. p. 135-7.

- Halil İnalcık. The Origin of the Ottoman-Russian Rivalry. p. 79-80.

- Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History. p. 33.

The project was abandoned when one-third complete

- Colin Imber. The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power. p. 44.

- A. N. Kurat. "The Turkish Expedition to Astrakhan' in 1569 and the Problem of the Don-Volga Canal". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/where-is-the-volga-don-canal.html

- Ilovlya (river in the RSFSR) // Great Soviet Encyclopedia : [in 30 vol.] / Ch. ed. A.M. Prokhorov . - 3rd ed. - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969-1978.

- Minh A. N. Historical and Geographical Dictionary of the Saratov Province / Comp. A.N. Minh. - Saratov, 1898-1902. - 5 t. - App. To the Works of the Saratov Scientific Archival Commission. - S. 383

- https://vetert.ru/rossiya/volgogradskaya-oblast/sights/232-gorod-petrov-val.php

- Плечко Л.А.: Старинные водные пути. Сервер для туристов и путешественников Скиталец. Информационный сервер обо всех видах туризма (in Russian). Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- это... Что такое Ивановский канал?. Словари и энциклопедии на Академике (in Russian). Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Skolkov G.S. Tsaritsyn-Stalingrad in the past . - Stalingrad: Edition of the Stalingrad island of local history, 1928. - T. The first essay, 1589-1862.

- Collection of freight surface distances of Russian railways / Comp. I.F.Sauer. - St. Petersburg: Br. Panteleev, 1893. - S. 10. - 114 p.

- Minh A.N. Dubovsko-Kachalinskaya railway // Historical and geographical dictionary of the Saratov province. - Saratov: Printing house of the provincial zemstvo, 1898. - T. 1, issue 2. - S. 276-277.

- Морская коллегия: Речной транспорт Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Maritime Board: River Transport) (in Russian)

- "Взвесить все" (Supplement to the Kommersant newspaper, No. 195/P(4012), 27.10.2008 (in Russian)

- «Водный мир» для Евразии ("Eurasia's 'Water World'"; Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine), Transport Rossii, No. 28 (472) 12 July 2007 (in Russian).

- http://www.ng.ru/energy/2016-01-12/15_aes.html

- Петр ГОДЛЕВСКИЙ, «ВОЛГО-ДОН 2» — ШАГ В БУДУЩЕЕ. «Торговая газета», номер 4-5(434—435) от 23.01.2008

- D. J. Peterson, «Troubled Lands: The Legacy of Soviet Environmental Destruction»Chapter 3

- "ВОЛГО-ДОН-II: МЫ СТРОИЛИ, СТРОИЛИ И ЧТО?" (We have been building... So what?") Журнал «Власть» (Kommersant-Vlast Magazine), No. 30, 30.07.1990 (in Russian)

- "Строительство второго Волго-Донского канала, на нужды которого в свое время было затрачено 750 миллионов рублей, было заморожено 10 лет назад. А приехавшие по призыву комсомола люди так и остались там жить." (14.11.2000)

- Nazarbayev insists on Eurasian canal construction Archived 5 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine Kazinform, 22 May 2008

- "Top News, Latest headlines, Latest News, World News & U.S News - UPI.com". UPI. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.