Uvac Special Nature Reserve

Uvac Special Nature Reserve (Serbian: Специјални резерват природе Увац) is a special nature reserve of the category I in Serbia. It is known for the successful project of the preservation of the griffon vulture.

| Uvac | |

|---|---|

| (Serbian: Увац) | |

IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) | |

The bridge over Uvac | |

Uvac Nature Reserve | |

| Location | |

| Nearest city | Nova Varoš, Sjenica |

| Coordinates | 43°25′37″N 19°56′03″E |

| Area | 75.43 km2 (29.12 sq mi) |

| Established | 1971 |

| Visitors | 12,000 (in summer 2017) |

| Specijalni rezervat prirode Uvac | |

Location

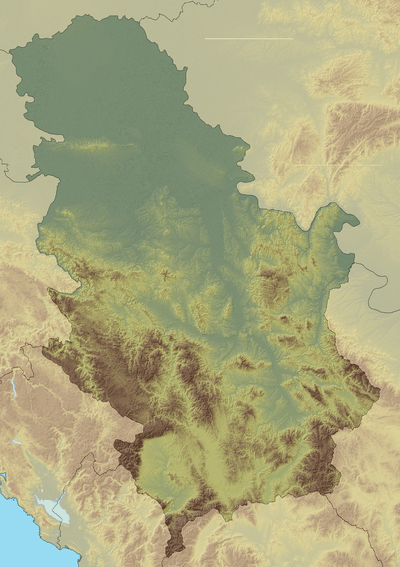

The reserve is located in the southwestern Serbia, in the municipalities of Nova Varoš (approximately 2/3) and Sjenica (1/3) in the Zlatibor District. The protected area is elongated and comprises the valley of the Uvac river, including the Uvac Gorge.[1]

Geography

Geographically, the Uvac valley is part of the Stari Vlah-Raška highland. It is surrounded by the mountains of Zlatar on the west, Murtenica and Čemernica on the north, Javor on the east and Jadovnik on the south. The lowest point in the reserve is 760 m (2,490 ft) and the highest 1,322 m (4,337 ft). Central morphological section is actually a canyon-like valley of the river, including the valleys of its tributaries. The river cut its bed deep into the limestone rocks and formed a narrowed gorge-canyon valleys with high and steep limestone cliffs. An average deep of the valley is between 200 m (660 ft) and 300 m (980 ft) with the deepest section being 350 m (1,150 ft). The Uvac gorge is especially known for its "pinched" meanders, or meanders which are cut in the canyon-like fashion. Relative height of the meanders reaches some 100 m (330 ft) near the village of Gornje Lopiže. Photos of the meanders are often used in the promotional touristic publications from Serbia.[1]

There are 12 arranged lookouts in the gorge. The most popular three are Veliki Krš ("Great Karst"), Veliki Vrh ("Great Peak") and Molitva ("Prayer"). The best known panoramic images of the gorge were made from these three points.[2]

The terrain is karst in nature, with numerous karstic features: karst plains, uvalas, sinkholes, caves, pits and rock shelters. Caves are numerous and vary in size, from cavelets to one of the largest cave systems in Serbia. So far, 6,185 m (20,292 ft) of the Ušak Cave system has been explored, which, as of 2017, makes it the third longest cave in Serbia, after the Lazar's Cave and Cerje Cave.[3] The system consists of two caves, Ušak and Ledena (Ice cave), which are connected by the Bezdan pit (The Abyss). Other caves in the reserve include Tubića, Durulja and Baždarska caves. They are all rich in speleothems: stalactites, stalagmitess, drapes and frostwork.[1] It is estimated that the Ušak system is 250 million years old, but is still being geologically active.[4]

Waters of the Uvac river are used for three hydroelectric power stations within the reserve, each one with an artificial lake: Bistrica with Radoinja Lake (1960), Kokin Brod with Zlatar Lake (1962) and Sjenica with Sjenica Lake (1979).[5]

Wildlife

Plants

There are 219 plant species in the reserve. Of them, 3 are of international importance, 3 are listed in the Red list, 25 are placed under the controlled regime of picking and trading and 50 are believed to have medicinal properties.[1]

Animals

In the Uvac river and its tributaries within the reserve, there are 24 species of fish. Clean water in rivers and reservoirs are natural spawning locations for huchen, brown trout (borth faria and lacustris morphs), brook trout, zander, Mediterranean barbel, common nase and European chub.[1]

Mammalian fauna includes wolves, bears, wild boars, foxes, hares, badgers and European pine martens, some of which are declared rare and endangered in Serbia.[1]

Birds

The main attraction in the reserve is the avifauna, with 172 bird species. The most important inhabitant of Uvac is the griffon vulture, one of two remaining vulture species which nests in Serbia. Large bird, with a wingspan of up to 3 m (9.8 ft), it has a unique place in the ecosystem's food chain as it feeds solely on carcasses, providing the "natural recycling". In the years after the World War II, the species was on the brink of extinction. In order to save the birds, an area of the Uvac gorge was protected in 1971, but still, number of birds reduced to only 7 in the 1970s and 10 in 1990. At that moment, it appeared that the species will go extinct as it already disappeared from eastern Serbia, Romania, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. Situation began to improve when in 1994 the Manastirina feeding ground was established. By 2017, the number of griffon vultures grew to 110 nesting couples and almost 500 birds altogether. That is the largest colony of griffon vultures in the Balkans and one of the largest in Europe, with probably only colony in Spain being larger.[1][4][6][7]

The griffon vultures from Uvac roam all over the Europe and Middle East. Birds tagged in Uvac have been spotted in 18 countries, ranging from Spain on the west to Yemen, 4,000 km (2,500 mi) on the southeast. Seven birds have been detected in 2,000 km (1,200 mi) away Israel which later returned to Uvac. For example, a female named Sara, which hatched in Uvac in 2011, was caught and satellite-tagged in Israel in 2012. After reaching sexual maturity, she returned to Serbia in 2017. Tracking devices showed that some birds were flying high up to 10 km (6.2 mi). One male flew north to Poland and got injured there. Polish ambassador transported it back to the Uvac by plane, it was healed and named Uroš the Weak, after the last Serbian emperor. He became a touristic attraction.[4] Another celebrity resident was a female named Dobrila. She hatched in 2018 in the Orlovica locality and on her maiden long-distance voyage that same year, she flew to the Turkish-Syrian border where she was found completely exhausted. In the spring of 2019, a special flight was arranged for her and she was transported back to Uvac by the plane. In December 2020 she was found dead in the reserve, stuck between the four entangled hornbeam canopies.[8]

As the population is thriving, there are less and less suitable locations for the nesting in the reserve. In 2009, a project for reintroduction of the griffon vultures to the Stara Planina was prepared. The birds used to live in this area of Eastern Serbia, on the border with Bulgaria, but went extinct in the late 1940s. Due to the financial difficulties, the project was put on hiatus, though not scrapped.[6] The reintroduction program continued in 2017 within the scope of a wider European program. Among other things, the feeders will be placed along the vultures' migratory route.[9]

The camera, which is installed at the feeding ground, recorded the showing of two other vulture species which were extinct from these areas: cinereous vulture and Egyptian vulture. The administration of the reserve, in association with the "Siniša Stanković Institute for Biological Research" and the "Institute for nature conservation of Serbia", wishes to implement the reintroduction project of another vulture species which went extinct in the region, the bearded vulture. Other birds in the protected area include many species of hawks, owls and, especially, eagles: white-tailed eagle, golden eagle, common buzzard and short-toed snake eagle. Uvac is also one of the rare nesting areas of goosander in Serbia and location of the largest recorded population of this bird in the Balkans.[1]

In 2017 the environmentalists warned that excessive tourism endangers the griffon vultures. The touristic guides often divert from the boat touristic routes, bring the tourists closer to the nests and even scare the birds so that they would fly and tourists can photograph them. In 2016/17, of the nests along the boat route, 12 were abandoned, 6 collapsed and from 2 the chicks fell out.[9] Still, the birds got accustomed to the visitors. When tourists visit the lookouts, birds began to fly above, as they are expecting food. The chicks are so well fed, that instead of weighing 8 to 9 kg (18 to 20 lb), some weigh up to 12 to 13 kg (26 to 29 lb) and fall into the lakes. The rangers pick them up and return to the nests, until they lose some weight and learn to fly. In the summer season of 2017 there were 12,000 visitors.[4]

By the late 2018 there were almost 150 nesting couples of various vultures, and 600 individual birds. Tracking shows that, on average, one vulture flies for some 40 km (25 mi) daily, in the circling patterns. The massive terrace-like bolder which birds use to take off, is called the "Castle of griffons".[2]

Protection

The Uvac region was declared a protected area in 1971.[10] Today it covers an area of 75.43 km2 (29.12 sq mi).[1] In 2008, it was voted one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Serbia.[11]

In October 2018 the water level in the lake plunged for some 20 m (66 ft) in 20 days, but the level was generally going down for two months. The boats left on shore would get stranded for over 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) of dry land over night. The water was used by the Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS), a state-owned electric utility power company, for enlarged electricity production. In this period, the total length of the lake was shortened from 27 km (17 mi) to 23 km (14 mi). The EPS claimed that this is normal and that it will not harm the wildlife.[7] This coincided with the emptying of other accumulations in protected areas in other parts of Serbia (Lake Vlasina, Lake Zavoj). This prompted suspicions that the forcing of the electricity production is part of some scheme, in the case of Uvac, with the companies from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The EPS refuted these claims, too, saying that in previous periods, and especially in 2000 and 2012, the water level was much lower than today. Still, the company didn't disclose why are they emptying the lake.[12][13]

References

- Darko Ćirović (2017). "Kraljevstvo beloglavog supa" (in Serbian).

- Aleksandra Petrović (9 September 2018). "Pod krilima zaštićenog oral" [Under the wings of protected eagle]. Politika (in Serbian). pp. 08–09.

- "Najduže pećine i jame Srbije" (in Serbian). Akademski speleološko-alpinistički klub. 3 February 2011.

- Slavica Stuparušić (19 September 2017). "Prošlo hiljade turista, a nigde smeća" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 08.

- "Uvačka jezera" (in Serbian). 2017.

- Branka Vasiljević (14 May 2017). "Sara na Uvac doletela po mladoženju" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 08.

- Adam Santovac (18 October 2018). "N1 u rezervatu Uvac: Da li čudo prirode Srbije nestaje?" [N1 in the Uvac reserve: is the miracle of nature in Serbia disappearing?] (in Serbian). N1.

- Трагичан крај белоглавог супа Добриле [Tragic end of the griffon vulture Dobrila]. Politika (in Serbian). 6 December 2019. p. 12.

- Branka Vasiljević (5 September 2017), "Nekontrolisane posete turista ugrožavaju opstanak beloglavnog supa", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- "Uvac River Meanders". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- A.Cvetićanin (9 July 2017), "Uvac – skriveni dragulj Evrope", Politika (in Serbian), p. 20

- Branko Pejović (19 October 2018). "Da li je EPS ugrozio floru i faunu jezera Uvac" [Is EPS endangering the flaura and the fauna of the Lake Uvac]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 09.

- Nikola Kočović (14 October 2018). ""Uništiše nam jezero" Uvac potpuno presušio na pojedinim delovima, vodostaj opao 20 metara za dva meseca" ["They are destroying the lake" Uvac completely dried out in some sections, water level fell 20 meters in two months]. Blic (in Serbian).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Special Nature Reserve Uvac. |