Ub Iwerks

Ubbe Eert "Ub" Iwerks (/ˈʌb ˈaɪwɜːrks/; March 24, 1901 – July 7, 1971) was an American animator, cartoonist, character designer, inventor, and special effects technician, who designed Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse. Iwerks produced alongside Walt Disney and won numerous awards, including multiple Academy Awards.

Ub Iwerks | |

|---|---|

A publicity photograph (circa 1929) of Ub Iwerks and his most famous co-creation, Mickey Mouse | |

| Born | Ubbe Ert Iwwerks March 24, 1901 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | July 7, 1971 (aged 70) Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn - Hollywood Hills Cemetery |

| Occupation | Animator, cartoonist, film producer, special effects technician |

| Years active | 1920–1971 |

| Employer | Walt Disney Animation Studios (1923–1929, 1940–1965) Leon Schlesinger Productions (1937) Columbia Pictures (1937–1940) Cartoon Films Limited (1940) |

Notable work | Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Mickey Mouse |

| Spouse(s) | Mildred Sarah Henderson (m. 1927–1971) |

| Children | Don Iwerks David Iwerks |

| Relatives | Leslie Iwerks (granddaughter) |

Early life

Iwerks was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His father, Eert Ubbe Iwwerks, was born in the village of Uttum in East Frisia (northwest Germany, today part of the municipality of Krummhörn) and immigrated to the United States in 1869. The elder Iwwerks, who worked as a barber, was 57 when Ub was born and had fathered and abandoned several previous children and wives of his. When Ub was a teenager, he abandoned him as well, forcing the boy to drop out of school and work to support his mother. Iwerks despised his father and never spoke of him--upon learning that he had died, he reportedly said "Throw him in a ditch." Ub's full name, Ubbe Ert Iwwerks, can be seen on early Alice Comedies that he signed. Several years later he simplified his name to "Ub Iwerks", sometimes written as "U. B. Iwerks".[1]

He is the father of Disney Legend Don Iwerks and grandfather of documentary film producer Leslie Iwerks.

Career

Iwerks was considered by many to be Walt Disney's oldest friend and spent most of his career with Disney. The two met in 1919 while working for the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio in Kansas City,[2] and eventually started their own commercial art business together.[3] Disney and Iwerks then found work as illustrators for the Kansas City Slide Newspaper Company[4] (which was later named The Kansas City Film Ad Company).[5] While working for the Kansas City Film Ad Company, Disney decided to take up work in animation,[6] and Iwerks soon joined him.

He was responsible for the distinctive style of the earliest Disney animated cartoons, and was also responsible for designing Mickey Mouse.[7] In 1922, when Disney began his Laugh-O-Gram cartoon series, Iwerks joined him as chief animator. The studio went bankrupt, however, and in 1923 Iwerks followed Disney's move to Los Angeles to work on a new series of cartoons known as “the Alice Comedies” which had live-action mixed with animation. After the end of this series, Disney asked Iwerks to design a character that became Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. The first cartoon Oswald starred in was animated entirely by Iwerks. Following the first cartoon, Oswald was redesigned on the insistence of Oswald’s owner and the distributor of the cartoons, Universal Pictures. The production company at the time, Winkler Pictures, gave additional input on the character’s design.

In spring 1928, Disney was removed from the Oswald series, and much of his staff was hired away to Winkler Pictures. He promised to never again work with a character he did not own.[8] Disney asked Iwerks, who stayed on, to start drawing up new character ideas. Iwerks tried sketches of frogs, dogs, and cats, but none of these appealed to Disney. A female cow and male horse were created at this time by Iwerks, but were also rejected. They later turned up as Clarabelle Cow and Horace Horsecollar.[9] Ub Iwerks eventually got inspiration from an old drawing. In 1925, Hugh Harman drew some sketches of mice around a photograph of Walt Disney. Then, on a train ride back from a failed business meeting, Walt Disney came up with the original sketch for the character that was eventually called Mickey Mouse.[10] Afterward, Disney took the sketch to Iwerks. In turn, he drew a more clean-cut and refined version of Mickey, but one that still followed the original sketch.

The first few Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies cartoons were animated almost entirely by Iwerks, including Steamboat Willie and The Skeleton Dance.[7] However, as Iwerks began to draw more and more cartoons on a daily basis, he chafed under Disney's dictatorial rule.[11] Iwerks also felt he wasn't getting the credit he deserved for drawing all of Disney's successful cartoons.[12] Eventually, Iwerks and Disney had a falling out; their friendship and working partnership were severed in January 1930. According to an unconfirmed account, a child approached Disney and Iwerks at a party and asked for a picture of Mickey to be drawn on a napkin, to which Disney handed the pen and paper to Iwerks and stated, "Draw it." Iwerks became furious and threw the pen and paper, storming out. Iwerks accepted a contract with Disney competitor Pat Powers to leave Disney and start an animation studio under his own name. His last Mickey Mouse cartoon was The Cactus Kid.[13] (Powers and Disney had an earlier falling-out over Disney's use of the Powers Cinephone sound-on-film system—actually copied by Powers from DeForest Phonofilm without credit—in early Disney cartoons.)

The Iwerks Studio opened in 1930. Financial backers led by Pat Powers suspected that Iwerks was responsible for much of Disney's early success. However, while animation for a time suffered at Disney from Iwerks' departure, it soon rebounded as Disney brought in talented new young animators.

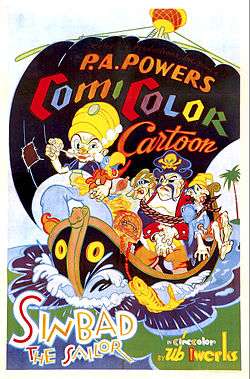

Despite a contract with MGM to distribute his cartoons, and the introduction of a new character named “Flip the Frog”, and later “Willie Whopper”, the Iwerks Studio was never a major commercial success and failed to rival either Disney or Fleischer Studios. Newly-hired animator Fred Kopietz recommended that Iwerks employ a friend from Chouinard Art School, Chuck Jones, who was hired and put to work as a cel washer.[7] The Flip and Willie cartoons were later distributed on the home-movie market by Official Films in the 1940s. From 1933 to 1936, he produced a series of shorts (independently distributed, not part of the MGM deal) in Cinecolor, named ComiColor Cartoons. The ComiColor series mostly focused on fairy tales with no continuing character or star. Later in the 1940s, this series received home-movie distribution by Castle Films. Cinecolor produced the 16 mm prints for Castle Films with red emulsion on one side and blue emulsion on the other. Later in the 1970s Blackhawk Films released these for home use, but this time using conventional Eastmancolor film stock. They are now in the public domain and are available on VHS and DVD. He also experimented with stop-motion animation in combination with the multiplane camera, and made a short called The Toy Parade, which was never released in public.[14] In 1936, backers withdrew financial support from the Iwerks Studio, and it folded soon after.

In 1937, Leon Schlesinger Productions contracted Iwerks to produce four Looney Tunes shorts starring Porky Pig and Gabby Goat. Iwerks directed the first two shorts, while former Schlesinger animator Robert Clampett was promoted to director and helmed the other two shorts before he and his unit returned to the main Schlesinger lot. Iwerks then did contract work for Screen Gems (then Columbia Pictures' cartoon division) where he was the director of several of the Color Rhapsodies shorts before returning to work for Disney in 1940.

After his return to the Disney studio, Iwerks mainly worked on developing special visual effects. He is credited as developing the processes for combining live-action and animation used in Song of the South (1946), as well as the xerographic process adapted for cel animation. He also worked at WED Enterprises, now Walt Disney Imagineering, helping to develop many Disney theme park attractions during the 1960s. Iwerks did special effects work outside the studio as well, including his Academy Award nominated achievement for Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963).

Iwerks' most famous work outside creating and animating Mickey Mouse was Flip the Frog from his own studio. According to Chuck Jones, who worked for him, "He was the first, if not the first, to give his characters depth and roundness. But he had no concept of humor; he simply wasn't a funny guy."

Death

Iwerks died in 1971 of a heart attack in Burbank, California, aged 70, and his ashes interred in a niche in the Columbarium of Remembrance at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills Cemetery.

Influence and tributes

The Ub Iwerks Award for Technical Achievement, as part of the Annie Awards, is named in his honour.

A rare self-portrait of Iwerks was found in the garbage bin at an animation studio in Burbank. The portrait was saved and is now part of the Animation Archives in Burbank, California.

After the Second World War, much of Iwerks' early animation style was imitated by legendary manga artists Osamu Tezuka and Shōtarō Ishinomori.

In 1989, Iwerks was named a Disney Legend.

In the 1996 The Simpsons episode "The Day the Violence Died", a relationship similar to Iwerks' early relationship with Walt Disney is used as the main plot.

A documentary film, The Hand Behind the Mouse: The Ub Iwerks Story, was released in 1999, followed by a book written by Iwerks' granddaughter Leslie Iwerks and John Kenworthy in 2001. The documentary, created by Leslie Iwerks, was released as part of The Walt Disney Treasures, Wave VII series (disc two of The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit collection).

A feature film released in 2014 Walt Before Mickey, showed how Ub Iwerks, portrayed by Armando Gutierrez, and Walt Disney, portrayed by Thomas Ian Nicholas, co-created Mickey Mouse.

The sixth episode from the second season of Drunk History ("Hollywood"), tells about Ub's work relationship with Disney, with stress on the creation of Mickey Mouse. Iwerks was portrayed in the episode by Tony Hale.

Filmography

1930

| Title | Release Date | Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiddlesticks | 8/16/1930 | Flip the Frog | • First cartoon by Ub Iwerks. • First Flip the Frog cartoon. • Filmed in two-strip Technicolor. |

| Little Orphan Willie | 10/18/1930 | Flip the Frog | |

| Flying Fists | 9/6/1930 | Flip the Frog | • Many sources claim that FF was filmed in two-strip Technicolor like Fiddlesticks, though this is incorrect. |

| The Village Barber | 9/27/1930 | Flip the Frog | • First non-woodland cartoon. |

| The Cuckoo Murder Case | 10/18/1930 | Flip the Frog | • First Halloween-themed cartoon. • First time a curse word is heard. The telephone in the detective office says "damn!" when it fails to wake up Flip. |

| Puddle Pranks | 12/06/1930 | Flip the Frog | • Final woodland-themed cartoon. This and Little Orphan Willie were never copyrighted. • Only appearance of Flip's frog girlfriend. |

1931

| Title | Release Date | Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Village Smitty | 1/31/1931 | Flip the Frog | • First appearances of Flip's cat girlfriend and Orace. |

| The Soup Song | 1/31/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Bandmaster Paul Whiteman is caricatured. |

| Laughing Gas | 3/14/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Only appearance of the walrus. |

| Ragtime Romeo | 5/2/1931 | Flip the Frog | • First time Flip wears a hat. • Second time a curse word is heard. Flip says "damn!" when he fails to get his music sheet to stand up. |

| The New Car | 7/25/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Starting with this cartoon, Flip's design slowly changes. • Some plot elements in this cartoon are reused from a Disney Oswald cartoon, Trolley Troubles. |

| Movie Mad | 8/29/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Caricatures include Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin. |

| The Village Specialist | 9/12/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Only appearance of Mrs. Pig. |

| Jail Birds | 9/26/1931 | Flip the Frog | • First time Orace is Flip's horse. |

| Africa Squeaks | 10/17/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Currently not shown on American television due to offensive black stereotypes. |

| Spooks | 12/21/1931 | Flip the Frog | • Second Halloween-themed cartoon. |

1932

| Title | Release Date | Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Milkman | 2/20/1932 | Flip the Frog | • First appearance of the orphan boy. • The third time a curse word is heard. In the end, where Flip, the boy and Orace sing Hail, Hail, the Gang's All Here, Orace sings "What the hell do we care?". |

| Fire! Fire! | 3/5/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Fourth time a curse word is heard. Orace says "damn!" when he loses a game of checkers against Flip. |

| What a Life | 3/26/1932 | Flip the Frog | • First time Flip interacts with humans. |

| Puppy Love | 4/30/1932 | Flip the Frog | • First appearance of Flip's dog. |

| School Days | 5/14/1932 | Flip the Frog | • First appearance of the spinster. |

| The Bully | 6/18/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Final appearance of the orphan boy. |

| The Office Boy | 7/16/1932 | Flip the Frog | • The secretary is a caricature of Joan Crawford. • Contains inappropriate content. |

| Room Runners | 8/13/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Contains inappropriate content. • Fifth time a curse word is heard. Flip says "damn!" after he falls down a flight of stairs. |

| Stormy Seas | 8/22/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Possibly a withheld 1931 release. • Final appearance of Flip's cat girlfriend. |

| Circus | 8/27/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Copyrighted on September 7, 1932. |

| The Goal Rush | 10/3/1932 | Flip the Frog | • In the beginning, there is a scene considered inappropriate where the bandmaster shoots the clarinet player just for playing wrong. • First appearance of Flip's human girlfriend. |

| The Phoney Express | 10/27/1932 | Flip the Frog | • First "official" appearance of Flip's human girlfriend. She bears a strong resemblance to Fleischer Studios's Betty Boop. The original title for the cartoon was called "The Pony Express", but later changed to "The Phoney Express" by Pat Powers. |

| The Music Lesson | 10/29/1932 | Flip the Frog | • Only appearance of Flip's friends. |

| The Nurse Maid | 11/26/1932 | Flip the Frog | • This cartoon has two racist scenes that you won't find on TV. There's an angry "Chinaman–Fu Man Chu" type with long fingernails trying to scratch the eyes out of Flip. Later, a cigar store Indian has several gags with runaway animals. |

| Funny Face | 12/24/1932 | Flip the Frog | • In the public domain. |

1933

| Title | Release Date | Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coo Coo, the Magician | 1/21/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Cameo of the spinster at the beginning. |

| Flip's Lunchroom | 4/3/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Only Flip the Frog cartoon to have Flip's name in the title. |

| Technocracked | 5/8/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Many sources claim that this short was made in two-strip Technicolor, though this is incorrect. |

| Bulloney | 5/30/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Final time a curse word is heard. The bull says "damn!" after he's defeated by Flip. |

| A Chinaman's Chance | 6/24/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Currently not shown on American television due to offensive Chinese stereotypes Final appearance of Flip's dog. |

| Paleface | 8/12/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Final appearances of Orace, Flip's girlfriend, and the spinster. |

| The Air Race | n/a | Willie Whopper | • The First Willie Whopper cartoon, however it was never released, due to a plot hole. A remake, Spite Flight, was released. |

| Play Ball | 9/16/1933 | Willie Whopper | • The First Official Willie Whopper cartoon. |

| Soda Squirt | 10/12/1933 | Flip the Frog | • Final Flip the Frog cartoon. Caricatures include Laurel and Hardy, Jimmy Durante, Buster Keaton, Rasputin, the Marx Brothers, Mae West, Joe E. Brown, and presumably Cesar Romero. |

| Spite Flight | 10/14/1933 | Willie Whopper | • A remake of the unreleased Willie Whopper Cartoon, The Air Race. |

| Stratos Fear | 11/11/1933 | Willie Whopper | |

| Jack and the Beanstalk | 12/23/1933 | Comicolor | • First Comicolor cartoon. |

1934

| Title | Release Date | Series | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Davy Jones Locker | 1/13/1934 | Willie Whopper | The First of the only 2 Willie Whopper cartoons to be filmed in Cinecolor. |

| The Little Red Hen | 2/16/1934 | Comicolor | |

| Hell's Fire | 2/17/1934 | Willie Whopper | • The only cartoon made by Ub Iwerks to have a curse word in the title. This is also the last of the only 2 Willie Whopper Cartoons filmed in Cinecolor. |

| Robin Hood, Jr. | 3/10/1934 | Willie Whopper | |

| The Brave Tin Soldier | 4/7/1934 | Comicolor | |

| Insultin' the Sultan | 4/14/1934 | Willie Whopper | |

| Puss in Boots | 5/17/1934 | Comicolor | two other prints exist |

| Reducing Creme | 5/19/1934 | Willie Whopper | |

| Rasslin' Round | 6/1/1934 | Willie Whopper | • Working title: Rasslin' Around |

| The Queen of Hearts | 6/25/1934 | Comicolor | |

| Cave Man | 7/6/1934 | Willie Whopper | • Music composed by Bennie Moten and his orchaestra. |

| Jungle Jitters | 7/24/1934 | Willie Whopper | • Not currently shown on American television due to offensive black stereotypes. |

| Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp | 8/10/1934 | ComiColor | |

| Good Scout | 9/1/1934 | Willie Whopper | • Music composed by McKinney's Cotton Pickers Stereotypes of ethnic (Chinese, Jewish, Black) boy scouts. |

| Viva Willie | 9/20/1934 | Willie Whopper | • Final Willie Whopper cartoon. After this cartoon, the rest will only be Comicolor cartoons. |

| The Headless Horseman | 10/1/1934 | Comicolor | |

| The Valiant Tailor | 10/29/1934 | Comicolor | |

| Don Quixote | 11/26/1934 | Comicolor | Preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 1998.[15] |

| Jack Frost | 12/24/1934 | Comicolor |

1935

All Comicolor shorts.

| Title | Release Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Little Black Sambo | 2/6/1935 | • Not currently shown on American television due to offensive black stereotypes. |

| Bremen Town Musicians | 3/6/1935 | |

| Old Mother Hubbard | 4/3/1935 | |

| Mary's Little Lamb | 5/1/1935 | |

| Summertime | 6/15/1935 | |

| Sinbad the Sailor | 7/30/1935 | |

| The Three Bears | 8/30/1935 | |

| Balloonland (aka The Pincushion Man) | 9/30/1935 | • This is known as both Balloonland and The Pincushion Man. |

| Simple Simon | 11/15/1935 | |

| Humpty Dumpty | 12/30/1935 |

1936

All Comicolor shorts.

| Title | Release Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ali Baba | 1/30/1936 | |

| Tom Thumb | 3/30/1936 | |

| Dick Whittington's Cat | 5/30/1936 | |

| Little Boy Blue (aka The Big Bad Wolf) | 7/30/1936 | • This cartoon is variously known both as Little Boy Blue and The Big Bad Wolf. |

| Happy Days | 9/30/1936 | • Last of the Comicolor cartoons. The last cartoon made prior to reorganizing the studio. |

1937–1941

- Contract work to Leon Schlesinger Productions – 2 cartoons

- Contract work to Screen Gems/Columbia Pictures – 17 cartoons (Iwerks was only personally involved with 16 of the Color Rhapsody series, the last cartoon in the deal was completed by Paul Fennell after Iwerks had left his own studio).

- In 1940, Iwerks produced his last series, Gran'pop Monkey, featuring the art of British illustrator Lawson Wood.[16] Three cartoons were made: "A Busy Day", "Beauty Shoppe" and "Baby Checkers".[17]

| Title | Release Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Skeleton Frolic | 1/29/1937 | Color Rhapsody |

| Baby Checkers' | ?/??/1940 | |

| Beauty Shoppe | ?/??/1940 | |

| A Busy Day | ?/??/1940 | Last Iwerks directed cartoon prior returning to Disney |

See also

References

- For example in the opening credits of Little Black Sambo (1935).

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 46.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), pp. 47–50.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 50.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 56.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 58.

- Maltin, L. (1987). Of mice and magic: A history of American animated cartoons (Rev. ed.). New York: New American Library.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 109.

- Kenworthy, John; The Hand Behind the Mouse, Disney Editions: New York, 2001. p. 53.

- Kenworthy, John; The Hand Behind the Mouse, Disney Editions: New York, 2001. p. 54.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 143.

- Neal Gabler, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (2006), p. 144.

- Kaufman, J.B.; Gerstein, David (2018). Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History. Cologne: Taschen. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-8365-5284-4.

- The Mouse Machine: Disney and Technology

- "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

- Stanchfield, Steve (March 20, 2014). ""Beauty Shoppe" (1940) with Gran' Pop Monkey". Cartoon Research. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 88. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

Further reading

- Leslie Iwerks and John Kenworthy, The Hand Behind the Mouse (Disney Editions, 2001) and documentary of the same name (DVD, 1999)

- Leonard Maltin, Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons (Penguin Books, 1987)

- Jeff Lenburg, The Great Cartoon Directors (Da Capo Press, 1993)