Bedknobs and Broomsticks

Bedknobs and Broomsticks is a 1971 American hybrid musical fantasy film directed by Robert Stevenson, produced by Bill Walsh and released by Walt Disney Productions and distributed by Buena Vista Distribution Company in North America on December 13, 1971. It is based upon the books The Magic Bedknob; or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons (1943) and Bonfires and Broomsticks (1947) by English children's author Mary Norton. The film, which combines live action and animation, stars Angela Lansbury and David Tomlinson.

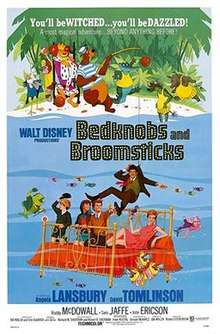

| Bedknobs and Broomsticks | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Stevenson |

| Produced by | Bill Walsh |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Magic Bedknob & Bonfires and Broomsticks by Mary Norton |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Irwin Kostal |

| Cinematography | Frank V. Phillips |

| Edited by | Cotton Warburton |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes (1971 original version) 139 minutes (1996 reconstruction version) |

| Country | United States[1][2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.3 million[3] |

| Box office | $17.9 million[4] |

During the early 1960s, Bedknobs and Broomsticks entered development when the negotiations for the film rights to Mary Poppins (1964) were placed on hold. When the rights were acquired, the film was shelved repeatedly due to the similarities with Mary Poppins until it was revived in 1969. Originally at a length of 139 minutes, Bedknobs and Broomsticks was edited down to almost two hours prior to its premiere at the Radio City Music Hall. The film was released on December 13, 1971 to mixed reviews from critics, some of whom praised the live-action/animated sequence. The film received five Academy Awards nominations winning one for Best Special Visual Effects. This was the last film released prior to the death of Walt Disney's surviving brother, Roy O. Disney, who died one week later. It is also the last theatrical film Reginald Owen appeared in before his death next year in 1972; his last two acting credits were for television.

In 1996, the film was restored with most of the deleted material re-inserted back into the film. A stage musical adaptation is in production which is set to debut in 2020.

Plot

During the Blitz, three children named Charlie, Carrie, and Paul Rawlins are evacuated from London to Pepperinge Eye, where they are placed in the reluctant care of Miss Eglantine Price, who agrees to the arrangement temporarily. The children attempt to run back to London, but after observing Miss Price attempting to fly on a broomstick, they change their minds. Miss Price reveals she is learning witchcraft through a correspondence school with hopes of using her spells in the British war effort, and offers the children a transportation spell in exchange for their silence. She casts the spell on a bedknob, and adds only Paul can work the spell, as he is the one who handed the bedknob to her. Later, Miss Price receives a letter from her school announcing its closure, thus preventing her from learning the final spell. She convinces Paul to use the enchanted bed to return the group to London, and locate Professor Emelius Browne.

Browne turns out to be a charismatic showman who created the course from an old book, and is shocked to learn the spells actually work for Miss Price. He gives the book to Miss Price, who is distraught to discover the final spell, "Substitutiary Locomotion", is missing. The group travels to Portobello Road to locate the rest of the book. After an exchange with an old bookseller, Miss Price learns that the spell is engraved on the Star of Astaroth, a medallion that belonged to a sorcerer of that name. The bookseller explains that the medallion was taken by a pack of wild animals, given anthropomorphism by Astaroth, to a remote island called Naboombu. A 17th century lascar had claimed to have seen Naboombu, but the bookseller never found it. Paul confirms its existence by recalling a storybook he found in Mr. Browne's playroom. The group travels to Naboombu and land in a lagoon; there, the bed goes underwater, where Mr. Browne and Miss Price enter a dance contest and win first prize. Just then, the bed is fished out of the sea by a bear, who informs the group that no human is allowed on the island by royal decree. They are brought before the island's ruler King Leonidas, who is wearing the Star of Astaroth. Leonidas invites Mr. Browne to act as a referee in a football match. The chaotic match ends in Leonidas' self-proclaimed victory, but Mr. Browne cleverly swaps the medallion with his referee whistle as he leaves. Upon discovering the theft, Leonidas pursues the group, but Miss Price transforms him into a white rabbit, and they escape.

Back home, Miss Price exercises the spell, which imbues inanimate objects with life. When Miss Price is informed that the children can be moved to another home, she decides to let them stay, but Mr. Browne, wary of commitment, attempts to return to London. A platoon of Nazi commandos land on the coast and invade Miss Price's house, imprisoning her and the children in the local museum. After observing more Nazis disabling phone lines, Mr. Browne comes to the rescue, inspiring Miss Price to use the spell to enchant the museum's exhibits into an army. The army of knights' armor and military uniforms chase the Nazis away, but as the Nazis retreat, they destroy Miss Price's workshop, ending her career as a witch. Though disappointed her career is over, she is happy she played a small part in the war effort. Shortly afterwards, Mr. Browne enlists in the army, and departs with the local Home Guard escorting him, and promising the children he will return one day soon. Paul reveals he still has the enchanted bedknob, hinting they can continue on with their adventures.

Cast

- Angela Lansbury as Miss Eglantine Price. Miss Price is initially a somewhat reclusive woman, reluctant to take in children from London as she believes they will get in the way of her witchcraft, which she prefers to keep secret but hopes to use to bring the nascent World War II to an end.

- David Tomlinson as Mr. Emelius Browne. Introduced as "Professor Browne," the title by which Miss Price knows him, he is running a Correspondence College of Witchcraft based on what he believes to be "nonsense words" found in an old book. When Miss Price and the children find him in London, he is revealed to be a street performer and con artist, and not a very good one. He is, however, a smooth talker, which proves useful on the group's adventures, and believes in doing everything "with a flair." As the adventures unfold, he finds himself developing an attachment to Miss Price and the children, a feeling he struggles with.

- Ian Weighill as Charles "Charlie" Rawlins. Charlie is the eldest of the orphaned Rawlins children; eleven, going on twelve, according to Carrie, an age which Miss Price calls "The Age of Not Believing." Accordingly, he is initially cynical and disbelieving of Miss Price's magical efforts, but comes around as time goes on; it is at his initial suggestion that Ms. Price uses the Substitutiary Locomotion spell on the museum artifacts.

- Cindy O'Callaghan as Carrie Rawlins. Slightly younger than Charlie, she takes on a motherly attitude toward her brothers, especially Paul. She is the first to encourage a friendly relationship between Miss Price and the children.

- Roy Snart as Paul Rawlins. Paul is about six; his possession of the bedknob and the Isle of Naboombu children's book lead to the group's adventures as well as the eventual solution to the quest for the Substitutiary Locomotion spell. Paul is prone to blurting out whatever is on his mind, which occasionally leads to trouble.

- Roddy McDowall as Mr. Rowan Jelk, the local clergyman. Deleted scenes reveal Mr. Jelk to be interested in marrying Miss Price, largely for her property.

- Sam Jaffe as the Bookman, a mysterious criminal also in pursuit of the Substitutiary Locomotion spell. It is implied that there is some history and bad blood between him and Mr. Browne.

- Bruce Forsyth as Swinburne, a spiv and associate of the Bookman's who acts as his muscle.

- Tessie O'Shea as Mrs. Jessica "Jessie" Hobday, the local postmistress of Pepperinge Eye and chairwoman of the War Activities Committee.

- John Ericson as Colonel Heller, leader of the German raiding party which comes ashore at Pepperinge Eye.

- Reginald Owen as Major General Sir Brian Teagler, commander of the local Home Guard.

- Arthur Gould-Porter as Captain Ainsley Greer, a British Army captain who comes from HQ in London to inspect the Home Guard and becomes lost in the area. He is constantly running into locals who suspect him of being a Nazi in disguise.

- Hank Worden as Old Home Guard Soldier (uncredited)

- Cyril Delevanti as Elderly farmer

- Alan Hewitt as a Soldier

Voices

- Lennie Weinrib as King Leonidas and Secretary Bird. The king is a lion, and a devoted football player with a fearsome temper, as well as a notorious cheat who is known to make up the rules as he goes along – according to Paul's book. His Secretary Bird is a prim and proper type who often bears the brunt of the king's temper.

- Dallas McKennon as Fisherman Bear. The Bear is a sailor and fisherman on the Isle of Naboombu who pulls the bed, with Miss Price's group on it, out of the lagoon with his fishing pole, and takes them to see the King after warning them of his temper.

- Bob Holt as Codfish, a denizen of the Naboombu lagoon.

Production

English author Mary Norton published her first children's book, The Magic Bed-Knob, in 1943. In August 1945, Variety reported that Walt Disney had purchased the film rights to the book. Norton then published Bonfires and Broomsticks in 1947, and the two children's books were then combined into Bed-Knob and Broomsticks in 1957. During the negotiations for the film rights to Mary Poppins with P.L. Travers in 1961, a film adaptation of Bedknobs and Broomsticks was suggested as an alternative project. When the negotiations stalled, Disney instructed the Sherman brothers to begin working on the project.[5] During a story conference with producer Bill Walsh and writer Don DaGradi, as the Sherman brothers were singing the song "Eglantine", Walt fell asleep in his chair.[6] When Disney purchased the rights to Mary Poppins, the project was shelved.[5][7]

In spring 1966, the Sherman brothers resumed their work on Bedknobs and Broomsticks, but the project was shelved again due to the similarities with Mary Poppins (1964). As the Sherman brothers' contract with the Disney studios was set to expire in 1968, they were contacted by Bill Walsh in their office to start work on the film. Then, Walsh, DaGradi, and the Sherman brothers re-assembled to work on the storyline for several months. Although there was no plan to put the film into production at the time, Walsh promised the Shermans that he would call them back to the studio and finish the project, which he eventually did in November 1969.[7] Throughout 1970 and 1971, the Sherman brothers reworked their musical compositions for the film. The song, "The Beautiful Briny" was originally written for Mary Poppins for when Mary spins a compass sending the Banks children into several exotic locations, but it was later used for Bedknobs and Broomsticks.[8][9]

Casting

Leslie Caron, Lynn Redgrave, Judy Carne, and Julie Andrews were all considered for the role of Eglantine Price.[10] Andrews was initially offered the part, but hesitated. Walsh later contacted Angela Lansbury, who signed onto the role on October 31, 1969. Shortly after, Andrews contacted Walsh again only to learn that Lansbury had been cast.[11][12] Although Peter Ustinov was considered,[12] Ron Moody was originally slated as Emelius Brown, but he refused to star in the film unless he received top billing which the studio would not allow. He was ultimately replaced with David Tomlinson.[10]

The three Rawlins children—Charlie, Carrie, and Paul—were played by Ian Weighill, Cindy O'Callaghan, and Roy Snart respectively. Weighill had previously dropped out of school and began his acting career in an uncredited role as a schoolboy in David Copperfield (1969). He auditioned before Disney talent scouts for one of the child roles in Bedknobs and Broomsticks in London, and was cast as Charlie. Prior to Bedknobs, Snart was a child actor appearing in numerous commercials, and was cast as Paul for his "impish, cheeky look".[13] For the part of Carrie, O'Callaghan explained that "casting directors trawled schools looking for children with London accents. I was asked to attend an audition at Pinewood, where I had to stand up and tell a funny story. I talked about how horrible my older brothers were to me. I was a big fan of Mary Poppins and couldn't believe I was going to be in a Disney film."[14]

Filming

Filming took place at the Disney studios in Burbank, California from early March to June 10, 1970.[15] The coastal scenes featuring Nazi soldiers were shot on location at a nearby California beach. Additional scenes were shot on location in Corfe Castle in Dorset, England.[12] Filming lasted fifty-seven days while the animation and special effects required five months each to complete.[16]

For the Naboombu soccer sequence, the sodium vapor process was used, which was developed by Petro Vlahos in the 1960s.[17] Animator and director Ward Kimball served as the animation director over the sequence.[18] Directing animator Milt Kahl had designed the characters, but he was angered over the inconsistencies in the character animation. This prompted Kimball to send a memo dated on September 17, 1970 to adhere to animation cohesiveness to the animation staff.[19] Because of the heavy special effects, the entire film had to be storyboarded in advance, shot for shot, in which Lansbury noted her acting was "very by the numbers".[20]

Release

Bedknobs and Broomsticks had an original runtime of 141 minutes, and was scheduled to premiere at the Radio City Music Hall. However, in order to accommodate for the theater's elaborate stage show, the film had to be trimmed down to two hours, in which 23 minutes were ultimately removed from the film. The removed scenes included a minor subplot involving Roddy McDowall's character (which was reduced to one minute) and three entire musical sequences titled "A Step in the Right Direction", "With a Flair", and "Nobody's Problems".[21] The "Portobello Road" sequence was reduced from about ten minutes down to three.[22][23]

The movie was reissued theatrically on April 13, 1979, with a shorter running time of 96 minutes and all songs, excluding "Portobello Road" and "Beautiful Briny Sea", muted out.

1996 restoration

Intrigued with the song "A Step in the Right Direction" on the original soundtrack album, Scott MacQueen, then-senior manager of Disney's library restoration, set out to restore the film in conjunction with the film's 25th anniversary.[12] Most of the deleted film material was found, but some segments of "Portobello Road" had to be reconstructed from work prints with digital re-coloration to match the film quality of the main content.[23] The footage for "A Step in the Right Direction" was never recovered,[23] but a reconstruction was used from the original music track linked up to existing production stills. The edit included several newly discovered songs, including "Nobody's Problems", performed by Lansbury. The number had been cut before the premiere of the film. Lansbury had only made a demo recording, singing with a solo piano because the orchestrations would have been added when the picture was scored. When the song was cut, the orchestrations had not yet been added; therefore, it was finally orchestrated and put together when it was placed back into the film.

The soundtrack for some of the spoken tracks was unrecoverable. Therefore, Lansbury and McDowall re-dubbed their parts, while other actors made ADR dubs for those who were unavailable. Even though David Tomlinson was still alive when the film was being reconstructed, he was in ill-health, and unavailable to provide ADR for Emelius Browne.[23]

The restored version of the film premiered on September 27, 1996 at the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, California where it was attended by Lansbury, the Sherman Brothers, Ward Kimball, and special effects artist Danny Lee.[12] It was later broadcast on Disney Channel on August 9, 1998.[23]

Home media

In 1980, Disney partnered with Fotomat Corporation on a trial distribution deal,[24] in which Bedknobs and Broomsticks was released on VHS and LaserDisc on March 4, 1980. In October 1982, Disney announced it had partnered with RCA to release nine of their films on the CED videodisc format[25] of which Bedknobs and Broomsticks was re-released later that same year. The film was re-issued on VHS on October 23, 1989, (with closed-captioning provided by Captions, Inc., Los Angeles).[26] The film was released on VHS as an installment in the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection on October 28, 1994.[27]

The restored version of the film was released on VHS and DVD on March 20, 2001 as part of the Walt Disney Gold Classic Collection, to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the film.[28] The reconstruction additionally marked the first time the film was presented in stereophonic sound. Along with the film, the DVD included a twenty-minute making-of featurette with the Sherman brothers, a recording session with David Tomlinson singing the ending of "Portebello Road", a scrapbook containing thirteen pages of concept art, publicity, and merchandising stills, and a Film Facts supplement of the film's production history.[29]

A new edition called Bedknobs and Broomsticks: Enchanted Musical Edition was released on DVD on September 8, 2009. This new single-disc edition retained the restored version of the film and most of the bonus features from the 2001 DVD release.[30] The movie was released on Special Edition Blu-ray, DVD, and Digital HD on August 12, 2014, in its original 117-minute version, with the deleted scenes used in the previous reconstructed version presented in a separate section on the Blu-ray disc.

Reception

Box office

During its initial release, the film grossed $17.6 million,[31] in which it earned $8.5 million in North American rentals.[32] The 1979 re-release increased its North American rentals to $11.4 million.[33]

Critical reaction

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film is a "tricky, cheerful, aggressively friendly Walt Disney fantasy for children who still find enchantment for pop-up books, plush animals by Steiff and dreams of independent flight." He further highlighted the Naboombu live-action/animated sequence as "the best of Disney, going back all the way to the first Silly Symphonies."[34] Variety also praised the Naboombu sequence as "not only sheer delights but technical masterpieces."[35] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times awarded the film two-and-a-half stars out of four, and claimed while the film has the "same technical skill and professional polish" as Mary Poppins, "[i]t doesn't have much of a heart, though, and toward the end you wonder why the Poppins team thought kids would like it much."[36] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave it two stars out of four and called it "a mishmash of story ideas and film styles," adding, "The difference between scenes of sea horses and storm troopers is so great that probably no story could manage it. 'Bedknobs' tries and fails."[37]

Pauline Kael, reviewing for The New Yorker, panned the film writing it has "no logic in the style of the movie, and the story dribbles on for so long that it exhausts the viewer before that final magical battle begins." She concluded her review claiming "This whole production is a mixture of wizardry and ineptitude; the picture has enjoyable moments but it's as uncertain of itself as the title indicates."[38] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote the film was "pleasant enough and harmless enough. It is also long (almost two hours) and slow. The songs are perfunctory (nothing supercalifragi-whatever) and the visual trickeries, splendid as they are, are sputtery to get the picture truly airborne. By the standards Disney has set for itself, it's a disappointing endeavor."[39] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that the film has an approval rating of 65% with an average rating of 6.15/10 out of 33 reviews.[40]

Accolades

For the 44th Academy Awards, the film was nominated for five Academy Award nominations for Best Art Direction, Best Scoring, Best Costume Design, Best Original Song, and Best Visual Effects, in which the film won the latter award.[22]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globe Awards | February 6, 1972 | Best Actress – Motion Picture Comedy or Musical | Angela Lansbury | Nominated |

| Academy Awards | April 10, 1972 | Best Special Visual Effects | Alan Maley, Eustace Lycett and Danny Lee | Won |

| Best Costume Design | Bill Thomas | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction | Art Direction: John B. Mansbridge and Peter Ellenshaw; Set Decoration: Emile Kuri and Hal Gausman | Nominated | ||

| Best Song Original for the Picture | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | Nominated | ||

| Best Scoring: Adaptation and Original Song Score | Song Score: Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman; Adaptation: Irwin Kostal | Nominated |

Soundtrack

| Bedknobs and Broomsticks | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1971 |

| Label | Walt Disney |

| Producer | Richard M. Sherman · Robert B. Sherman · Irwin Kostal |

The musical score for Bedknobs and Broomsticks was composed by Irwin Kostal, with all songs written by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman. A soundtrack album was released by Buena Vista Records in 1971. While the film was released in mono sound, the musical score was recorded in stereo and the soundtrack album was released in stereo. An expanded soundtrack album was later released on CD on August 13, 2002.

These songs include:

- "The Old Home Guard"

- "The Age of Not Believing" (received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song)

- "With a Flair" (only in the reconstruction)

- "Eglantine"

- "Don't Let Me Down" (only in the reconstruction)

- "Portobello Road"

- "The Beautiful Briny"

- "Substitutiary Locomotion"

- "A Step in the Right Direction"

- "Nobody's Problems" (only in the reconstruction)

- "Solid Citizen" (replaced by the soccer match)

- "Fundamental Element" (sections were incorporated into "Don't Let Me Down")

Stage musical

In March 2018, it was announced a stage musical adaptation of Bedknobs and Broomsticks was in the works with a book by Brian Hill, additional musical and lyrics by Neil Bartram (in addition to The Sherman Brothers songs), and was to be directed and choreographed by Rachel Rockwell. It would have made its world premiere at The Yard at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater from May 30 to July 28, 2019.[41] Now the decision on a premiere date and the new director and choreographer is still unclear.

Cultural influence

In the 1974 book William and Mary, by Penelope Farmer, the two title child characters experience a number of fantasy adventures. In Chapter 4, they go to a theater for a Disney film combining live action and animation, including an underwater sequence very similar to that in Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Afterwards they have an underwater adventure with cartoon fish which turn menacing.

References

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". American Film Institute. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". British Film Institute. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- Smith, Cecil (March 22, 1970). "Disney studios: it's a hardly a Mickey Mouse operation". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- Koenig 1997, pp. 145–6.

- Richard Sherman (September 21, 2009). "Richard M. Sherman on Bedknobs And Broomsticks: a Solid Songwriter!" (Interview). Interviewed by Jérémie Noyer. Animated Views. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Sherman & Sherman 1998, p. 162.

- Koenig 1997, p. 146.

- Sherman & Sherman 1998, p. 166.

- Maltin, Leonard (August 28, 2000). The Disney Films. Disney Editions. p. 262. ISBN 978-0786885275.

- Stirling, Richard (April 28, 2009). Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography. St. Martin's Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0312564988.

- "A Witch's Brew of a Perfect Movie". D23. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "3 English Children Get Big Break from Disney". Press & Sun-Bulletin. Binghamton, New York. March 25, 1972. Retrieved October 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A Great Future Behind Us! How Britain's Most Famous Child Stars Finally Found Obscurity - and Happiness". Daily Mail. London. March 27, 2004. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via HighBeam Research.

- LoBianco, Lorraine. "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Warga, Wayne (December 5, 1971). "Mr. Success, Spelled W-A-C-K-Y, of Disney's Fantasy Factory". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Foster, Jeff (2014). The Green Screen Handbook: Real-World Production Techniques (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 11–3. ISBN 978-1138780330.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks Feature Wonderland". The Daily Herald. Provo, Utah. September 27, 1971. Retrieved October 11, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Deja, Andreas (July 4, 2012). "Bedknobs & Broomsticks". Deja View. Blogger. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Angela Lansbury discusses "Bedknobs and Broomsticks" (Video). YouTube. Archive of American Television. July 17, 2018. Event occurs at 0:54.

- Sherman & Sherman 1998, p. 167.

- Arnold 2013, p. 104.

- King, Susan (August 7, 1998). "Unveiling a Polished-Up 'Bedknobs'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Quips: Invite Mickey Into Your Home". Orange Coast Magazine. February 1981. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "Disney, RCA Extend Pact". Billboard. Vol. 94 no. 39. October 2, 1982. p. 42. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Zad, Martie (September 27, 1989). "'Bambi' Released in Video Woods". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". Walt Disney Video. Archived from the original on June 8, 2000. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Imagination for a Lifetime -- Disney Titles All the Time; Walt Disney Home Video Debuts the Gold Classic Collection; An Animated Masterpiece Every Month in 2000" (Press release). Burbank, California. Business Wire. January 6, 2000. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via TheFreeLibrary.

- Cedeno, Kevin. "Bedknobs and Broomsticks 30th Anniversary Edition DVD Review". UltimateDisney.com. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks: Enchanted Musical Edition DVD Review". DVDizzy.com.

- Arnold 2013, p. 103.

- "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 44.

- "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 14, 1981. p. 54.

- Canby, Vincent (November 12, 1971). "Angela Lansbury in 'Bedknobs and Broomsticks'". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". Variety. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (November 24, 1971). "Bedknobs and Broomsticks". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via rogerebert.com.

- Siskel, Gene (November 24, 1971). "Knobs and Sticks". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 5.

- Kael, Pauline (May 15, 1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. Henry Holt and Company. p. 60. ISBN 978-0805013672.

- Champlin, Charles (November 19, 1971). "Mary Poppins on a Broomstick". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Hetrick, Adam (March 14, 2018). "Stage Adaptation of Disney's Bedknobs and Broomsticks Sets Chicago World Premiere". Playbill. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Mark (October 31, 2013). Frozen in Ice: The Story of Walt Disney Productions, 1966-1985. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1593937515.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koenig, David (1997). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 978-0964060517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherman, Robert; Sherman, Richard (1998). Walt's Time: from before to beyond. Camphor Tree Publishers. ISBN 978-0964605930.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bedknobs and Broomsticks |