The Rescuers

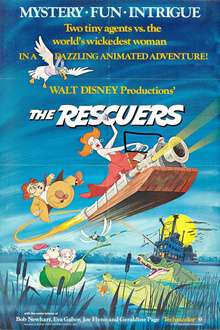

The Rescuers is a 1977 American animated adventure film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Buena Vista Distribution. The 23rd Disney animated feature film, the film is about the Rescue Aid Society, an international mouse organization headquartered in New York City and shadowing the United Nations, dedicated to helping abduction victims around the world at large. Two of these mice, jittery janitor Bernard (Bob Newhart) and his co-agent, the elegant Miss Bianca (Eva Gabor), set out to rescue Penny (Michelle Stacy), an orphan girl being held prisoner in the Devil's Bayou by treasure huntress Madame Medusa (Geraldine Page). The film is based on a series of books by Margery Sharp, most notably The Rescuers (1959) and Miss Bianca (1962).

| The Rescuers | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Rescuers and Miss Bianca by Margery Sharp |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Artie Butler |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 77 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $169 million[2] |

The Rescuers entered development in 1962, but was shelved due to Walt Disney's dislike of the project's political overtones. During the 1970s, the film was revived as a project for the younger animators, but it was taken over by the senior animation staff following the release of Robin Hood (1973). The Rescuers was released on June 22, 1977, to positive critical reception and became a box office success. The film was also successful throughout the world, including France and West Germany. Due to the film's success, a sequel titled The Rescuers Down Under was released in 1990, which made this film the first Disney animated film to have a sequel.

Plot

In an abandoned river boat in Devil's Bayou, a young orphan named Penny drops a message in a bottle, containing a plea for help into the river. The bottle washes up in New York City, where it is found by the Rescue Aid Society, an international mouse organization inside the United Nations. The Hungarian representative, Miss Bianca, volunteers to accept the case and chooses Bernard, a stammering janitor, as her co-agent. The two visit Morningside Orphanage, where Penny lived, and meet an old cat named Rufus. He tells them about a woman named Madame Medusa who once tried to lure Penny into her car and may have succeeded in abducting Penny this time.

The mice travel to Medusa's pawn shop, where they discover that she and her partner, Mr. Snoops, are on a quest to find the world's largest diamond, the Devil's Eye. The mice learn that Medusa and Mr. Snoops are currently at the Devil's Bayou with Penny, whom they have indeed kidnapped and placed under the guard of two trained crocodiles, Brutus and Nero. With the help of an albatross named Orville and a dragonfly named Evinrude, the mice follow Medusa to the bayou. There, they learn that Medusa plans to force Penny to enter a small hole that leads down into a pirates' cave where the Devil's Eye is located.

Bernard and Miss Bianca find Penny and devise a plan of escape. They send Evinrude to alert the local animals, who loathe Medusa, but Evinrude is delayed when he is forced to take shelter from a flock of bats. The following morning, Medusa and Mr. Snoops send Penny down into the cave to find the gem. Unbeknownst to Medusa, Miss Bianca and Bernard are hiding in Penny's skirt pocket. The three soon find the Devil's Eye within a pirate skull. As Penny pries the mouth open with a sword, the mice push it out from within, but soon the oceanic tide rises and floods the cave. The three barely manage to retrieve the diamond and escape.

Medusa breaks her promise to Snoops that he can have half the diamond, and hides it in Penny's teddy bear while holding Penny and Snoops at gunpoint. When she trips over a cable set as a trap by Bernard and Bianca, Medusa loses the bear to Penny, who runs away with it. The local animals arrive at the riverboat and aid Bernard and Bianca in trapping Brutus and Nero, then set off Snoops's fireworks to create more chaos. Meanwhile, Penny and the mice commandeer Medusa's swamp-mobile, a makeshift airboat. Medusa unsuccessfully pursues them, using Brutus and Nero as water-skis, and is left clinging to the boat's smoke stacks as Snoops escapes on a raft and laughs at her, while the irritated Brutus and Nero turn on her and circle below.

Back in New York City, the Rescue Aid Society watch a news report of how Penny found the Devil's Eye, which has been given to the Smithsonian Institution, and how she has been adopted. The meeting is interrupted when Evinrude arrives with a call for help, sending Bernard and Bianca on a new adventure.

Cast

- Bob Newhart as Bernard, Rescue Aid Society's timid janitor, who reluctantly tags along with Miss Bianca on her journey to the Devil's Bayou to rescue Penny. He is highly superstitious about the number 13 and dislikes flying (the latter being a personality trait of Newhart).

- Eva Gabor as Miss Bianca, the Hungarian representative of the Rescue Aid Society. She is sophisticated and adventurous, and fond of Bernard, choosing him as her co-agent as she sets out to rescue Penny. Her Hungarian nationality was derived from that of her voice actress.

- Geraldine Page as Madame Medusa, a greedy, redheaded, wicked pawnshop owner. Upon discovering the Devil's Eye diamond hidden in a blowhole, she kidnaps the small orphan, Penny, to retrieve it for her, as Penny is the only one small enough to fit in it. In the end, she is thwarted and presumably eaten by her two crocodiles, Brutus and Nero.

- Michelle Stacy as Penny, a lonely six-year-old orphan girl, residing at Morningside Orphanage in New York City. She is kidnapped by Medusa in an attempt to retrieve the world's largest diamond, the Devil's Eye.

- Joe Flynn as Mr. Snoops, Medusa's clumsy and incompetent business partner, who obeys his boss's orders to steal the Devil's Eye in exchange for half of it. Upon being betrayed by Medusa, however, he turns on her and flees by raft, laughing at her. This was Flynn's final role before his death in 1974.

- Jim Jordan as Orville (named after Orville Wright of the Wright brothers, the inventors of the airplane; most likely influenced from Bob Newhart's stand-up sketch "Merchandising the Wright Brothers"), an albatross who gives Bernard and Bianca a ride to Devil's Bayou. Jordan, 80 years old by the time the film was completed, had been lured out of retirement and had not performed since the death of his wife and comic partner Marian in 1961; it would serve as Jordan's last public performance.

- John McIntire as Rufus, an elderly cat who resides at Morningside Orphanage and comforts Penny when she is sad. Although his time onscreen is rather brief, he provides the film's most important theme, faith. He was designed by animator Ollie Johnston, who retired after the film following a 40-year career with Disney.

- Jeanette Nolan as Ellie Mae and Pat Buttram as Luke, two muskrats who reside in a Southern-style home on a patch of land in Devil's Bayou. Luke drinks very strong, homemade liquor, which is used to help Bernard and Evinrude regain energy when they need it. Its most important usage is for fuel for powering Medusa's swamp-mobile in the film's climax.

- James MacDonald as Evinrude (named after a brand of outboard motors), a dragonfly who mans a leaf boat across Devil's Bayou, giving Bernard and Miss Bianca a ride across the swamp waters.

- Bernard Fox as Mr. Chairman, the chairman to the Rescue Aid Society.

- George Lindsey as Deadeye, a fisher rabbit who is one of Luke and Ellie Mae's friends.

- Larry Clemmons as Gramps, a grumpy, yet kind old turtle who carries a brown cane.

- Dub Taylor as Digger, a mole.

- John Fiedler as Deacon Owl

- Shelby Flint as Singer, Bottle

- Bill McMillian as TV Announcer

Production

In 1962, the film began development with its initial treatment developed from the first book centering on a poet held captive by a totalitarian government in the Siberia-like stronghold. However, as the story grew overtly involved with international intrigue, Walt Disney shelved the project as he was unhappy with the political overtones.[3] The project was revived in the early 1970s as a project for the young animators, led by Don Bluth, as the studio would alternate between full-scale "A pictures" and smaller, scaled-back "B pictures" with simpler animation. The animators had selected the most recent book, Miss Bianca in the Antarctic, with its story focusing on a captured polar bear forced into performing in shows; causing the unsatisfied bear to place a bottle that would reach the mice.[3] Jazz singer Louis Prima was to voice the character named Louis the Bear, and this version was to feature six songs sung by Prima written by Floyd Huddleston.[4] However, in 1975, following headaches and episodes of memory loss, Prima discovered he had a stem brain tumor, and the project was scrapped.[5]

Meanwhile, the "A" crew had finished work on Robin Hood (1973), and was set to begin production on an adaptation of Paul Gallico's book titled Scruffy under the direction of Ken Anderson. Its story concerned the monkeys of Gibraltar under World War II that would be threatened by the Nazi Party's attempt to capture them from the British Empire during World War II. When the time had come to green-light one of the two projects, the studio leaders eventually decided to go for The Rescuers.[7] When Scruffy was shelved, the veteran team turned the project into a more traditional, full-scale production ultimately dropping the Arctic setting of the story with veteran Disney writer Fred Lucky stating, "It was too stark a background for the animators."[8] Cruella de Vil, the villainess from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), was originally considered to be the main antagonist of the film,[9] but veteran Disney animator Ollie Johnston stated it felt wrong to attempt a sequel and the idea was dropped.[10] Instead, she was replaced by a retouched version of the Diamond Duchess in Miss Bianca. The motive to steal a diamond originated in Margery Sharp's 1959 novel, Miss Bianca. Her appearance was based on animator Milt Kahl's then-wife, Phyllis Bounds (who was the niece of Lillian Disney), whom he did not particularly like. This was Kahl's last film for the studio, and he wanted his final character to be his best; he was so insistent on perfecting Madame Medusa that he ended up doing almost all the animation for the character himself.[11] Penny was inspired by Patience, the orphan in the novel. For the accomplices, the filmmakers adapted the character, Mandrake, into Mr. Snoops and his appearance was caricatured from animation historian John Culhane.[12] Culhane claims he was practically tricked into posing for various reactions, and his movements were imitated on Mr. Snoops's model sheet. However, he stated, "Becoming a Disney character was beyond my wildest dreams of glory."[13] Brutus and Nero are based on the two bloodhounds, Tyrant and Torment in the novels.[14][15]

The writers had considered developing Bernard and Bianca into married professional detectives, though they decided that leaving the characters as unmarried novices was more romantic.[16] For the supporting characters, a pint-sized swampmobile for the mice – a leaf powered by a dragonfly – was created. As they developed the comedic potential of displaying his exhaustion through buzzing, the dragonfly grew from an incidental into a major character.[8] Veteran sound effects artist and voice talent Jimmy MacDonald came out of retirement to provide the effects.[17] Also, the local swamp creatures were originally written as a dedicated home guard that drilled and marched incessantly. However, the writers evolved them into a volunteer group of helpful little bayou creatures. Their leader, a singing bullfrog voiced by Phil Harris, was deleted from the film.[16] A pigeon was originally proposed to be the transportation for Bernard and Bianca, until Ollie Johnston remembered a True Life Adventures episode that showed albatrosses and their clumsy take-offs and landings, and suggested the ungainly bird instead.[18]

Animation

Ever since One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), animation for theatrical Disney animated films was done by xerography, which had only been able to produce black outlines, but had been improved for the cel artists to use a medium-grey toner in order to create a softer-looking line.[19] At the end of production, it marked the last joint effort by veterans Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston, and Frank Thomas, and the first Disney film worked on by Don Bluth as a directing animator, instead of an assistant animator.[18] Other animators who stepped up during production were Glen Keane, Ron Clements, and Andy Gaskill, who would all play an important role in the Disney Renaissance.[20]

Music

| The Rescuers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album Vinyl LP by Various artists | ||||

| Released | 1977 | |||

| Recorded | 1974–77 | |||

| Label | Disneyland | |||

| Producer | Artie Butler | |||

| Walt Disney Animation Studios chronology | ||||

| ||||

The songwriting team of Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins first met in 1973 on a double date. Connors had earlier co-composed and sang successful songs such as "To Know Him Is to Love Him" and "Hey Little Cobra" with the Teddy Bears. Meanwhile, Robbins worked as a personal secretary to actors George Kennedy and Eva Gabor and wrote unpublished poetry. On their first collaboration, they composed eleven songs for a Christmas show for an unproduced animated film. In spite of this, they were offered an interview from Walt Disney Productions to compose songs for The Rescuers. Describing their collaborative process, Robbins noted "...Carol plays the piano and I play the pencil."[21] Additionally, Connors and Robbins collaborated with composer Sammy Fain on the song, "Someone's Waiting for You". Most of the songs they wrote for the film were performed by Shelby Flint.[22] Also, notably for the first time since Bambi (1942), all the most significant songs were sung as part of a narrative, as opposed to by the film's characters as in most Disney animated films.

Track listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Journey" | Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins | Shelby Flint | |

| 2. | "Rescue Aid Society" | Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins | Robie Lester (uncredited), Bob Newhart (uncredited), Bernard Fox (uncredited), and the Disney Studio Chorus | |

| 3. | "Tomorrow is Another Day" | Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins | Shelby Flint | |

| 4. | "Someone's Waiting for You" | Carol Connors, Ayn Robbins, and Sammy Fain | Shelby Flint | |

| 5. | "Tomorrow is Another Day (Reprise)" | Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins | Shelby Flint |

- Songs heard in the film but not released on the soundtrack

- "Faith is a Bluebird" – Although not an actual song, it is a poem recited by Rufus and partially by Penny in a flashback the old cat has to when he last saw the small orphan girl, and comforted her through the poem, about having faith. The titular bluebird that appears in this sequence originally appeared in Alice in Wonderland (1951).

- "The U.S. Air Force" - Serves as the leitmotif for Orville.

- "For Penny's a Jolly Good Fellow" – Sung by the orphan children at the end of the film, as a variation of the song "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow".

Release

During the film's initial theatrical run, the film was released as a double feature with the live-action nature documentary film, A Tale of Two Critters.[23] On December 16, 1983, The Rescuers was re-released to theaters accompanied with the new Mickey Mouse featurette, Mickey's Christmas Carol, which marked the character's first theatrical appearance after a 30-year absence. In anticipation of its upcoming theatrically released sequel in 1990, The Rescuers Down Under, The Rescuers saw another successful theatrical run on March 17, 1989.

Marketing

To tie in with the film's 25th anniversary, The Rescuers debuted in the Walt Disney Classics Collection line in 2002, with three different figures featuring three of the film's biggest stars, as well as the opening title scroll. The three figures were sculpted by Dusty Horner and they were: Brave Bianca, featuring Miss Bianca the heroine and priced at $75,[24] Bold Bernard, featuring hero Bernard, priced also at $75[25] and Evinrude Base, featuring Evinrude the dragonfly and priced at $85.[24] The title scroll featuring the film's name, The Rescuers and from the opening song sequence "The Journey," was priced at $30. All figures were retired in March 2005, except for the opening title scroll which was suspended in December 2012.[24]

The Rescuers was the inspiration for another Walt Disney Classics Collection figure in 2003. Ken Melton was the sculptor of Teddy Goes With Me, My Dear, a limited edition, 8-inch sculpture featuring the evil Madame Medusa, the orphan girl Penny, her teddy bear "Teddy" and the Devil's Eye diamond. 1,977 of these sculptures were made, in reference to the film's release year, 1977. The sculpture was priced at $299 and instantly declared retired in 2003.[25]

In November 2008, a sixth sculpture inspired by the film was released. Made with pewter and resin, Cleared For Take Off introduced the character of Orville into the collection and featured Bernard and Bianca a second time. The piece, inspired by Orville's take-off scene in the film, was sculpted by Ruben Procopio.[26]

Home media

The Rescuers premiered on VHS and Laserdisc on September 18, 1992 as part of the Walt Disney Classics series. The release went into moratorium on April 30, 1993.[27] It was re-released on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection on January 5, 1999, but was recalled three days later and reissued on March 23, 1999 (see "Controversy").

The Rescuers was released on DVD on May 20, 2003, as a standard edition, which was discontinued in November 2011.

On August 21, 2012, a 35th anniversary edition of The Rescuers was released on Blu-ray alongside its sequel in a "2-Movie Collection".[28][29]

Nudity scandal

On January 8, 1999, three days after the film's second release on home video, The Walt Disney Company announced a recall of about 3.4 million copies of the videotapes because there was an objectionable image in one of the film's backgrounds.[30][31][32][33]

The image in question is a blurry image of a topless woman with breasts and nipples showing. The image appears twice in non-consecutive frames during the scene in which Miss Bianca and Bernard are flying on Orville's back through New York City. The two images could not be seen in ordinary viewing because the film runs too fast — at 24 frames per second.[34]

On January 10, 1999, two days after the recall was announced, the London newspaper The Independent reported:

A Disney spokeswoman said that the images in The Rescuers were placed in the film during post-production, but she declined to say what they were or who placed them... The company said the aim of the recall was to keep its promise to families that they can trust and rely on the Disney brand to provide the best in family entertainment.[35]

The Rescuers home video was reissued on March 23, 1999, with the inappropriate nudity edited and blocked out.

Reception

Box office

The Rescuers was successful upon its original theatrical release earning worldwide gross rentals of $48 million at the box office.[36][37] During its initial release in France, it out-grossed Star Wars (1977) receiving admissions of 7.2 million.[38] The film also became the highest-grossing film in West Germany at the time with admissions of 9.7 million.[39][40] By the end of its theatrical run, the distributor rentals amounted to $19 million in the United States and Canada while its international rentals totaled $41 million.[41]

The Rescuers was re-released in 1983 in which it grossed $21 million domestically. The film was again re-released in 1989 and grossed $21.2 million domestically. In its total lifetime domestic gross, the film has grossed $71.2 million,[42] and its total lifetime worldwide gross is $169 million.[2]

Critical reaction

The Rescuers was said to be Disney's greatest film since Mary Poppins (1964), and seemed to signal a new golden age for Disney animation.[43] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times praised the film as "the best feature-length animated film from Disney in a decade or more—the funniest, the most inventive, the least self-conscious, the most coherent, and moving from start to finish, and probably most important of all, it is also the most touching in that unique way fantasy has of carrying vibrations of real life and real feelings."[44] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film "doesn't belong in the same category as the great Disney cartoon features (Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs, Bambi, Fantasia) but it's a reminder of a kind of slickly cheerful, animated entertainment that has become all but extinct."[45] Gene Siskel, reviewing the film for the Chicago Tribune, gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four writing "To see any Disney animated film these days is to compare it with Disney classics released 30 or 40 years ago. Judged against Pinocchio, for example. The Rescuers is lightweight, indeed. Its themes are forgettable. It's mostly an adventure story."[23]

TV Guide gave the film three stars out of five, opining that The Rescuers "is a beautifully animated film that showed Disney still knew a lot about making quality children's fare even as their track record was weakening." They also praised the voice acting of the characters, and stated that the film is "a delight for children as well as adults who appreciate good animation and brisk storytelling."[46] Ellen MacKay of Common Sense Media gave the film four out of five stars, writing, "Great adventure, but too dark for preschoolers".[47]

In his book, The Disney Films, film historian Leonard Maltin refers to The Rescuers as "a breath of fresh air for everyone who had been concerned about the future of animation at Walt Disney's," praises its "humor and imagination and [that it is] expertly woven into a solid story structure [...] with a delightful cast of characters." Finally, he declares the film "the most satisfying animated feature to come from the studio since 101 Dalmatians." He also briefly mentions the ease with which the film surpassed other animated films of its time.[48] The film's own animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston stated on their website that The Rescuers had been their return to a film with heart and also considered it their best film without Walt Disney.[49] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that the film received an 80% approval rating with an average rating of 6.4/10 based on 30 reviews. The website's consensus states that "Featuring superlative animation, off-kilter characters, and affectionate voice work by Bob Newhart and Eva Gabor, The Rescuers represents a bright spot in Disney's post-golden age."[50]

Jack Shaheen, in his study of Hollywood portrayals and stereotypes of Arabs, noted the inclusion of delegates from Arab countries in the Rescue Aid Society.[51]

Accolades

The Rescuers was nominated in 1978 for an Academy Award for the song "Someone's Waiting for You" at the 50th Academy Awards. The song lost to "You Light Up My Life" from the film of the same name.[52]

In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated The Rescuers for its Top 10 Animated Films list.[53]

Sequel

The Rescuers was the first Disney animated film to have a sequel. After three successful theatrical releases of the original film, The Rescuers Down Under was released theatrically on November 16, 1990.

The Rescuers Down Under takes place in the Australian Outback, and involves Bernard and Bianca trying to rescue a boy named Cody and a giant golden eagle called Marahute from a greedy poacher named Percival C. McLeach. Both Bob Newhart and Eva Gabor reprised their lead roles. Since Jim Jordan, who had voiced Orville, had since died, a new character, Wilbur (Orville's brother, another albatross) was created and voiced by John Candy.

See also

- 1977 in film

- List of American films of 1977

- List of highest-grossing animated films

- List of highest-grossing films in France

- List of animated feature films of 1977

- List of Walt Disney Pictures films

- List of Disney theatrical animated features

References

- Variety Staff. "Review: 'The Rescuers'". Variety. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (October 27, 2003). "Cartoon Coffers – Top-Grossing Disney Animated Features at the Worldwide B.O.". Variety. p. 6.

- Koenig 1997, pp. 153–54.

- Beck, Jerry (August 15, 2011). "Lost Louis Prima Disney Song". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- "This Day in Disney History – August 24". This Day in Disney History. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- Knowles, Rebecca; Bunyan, Dan (August 23, 2002). "Animal Heroes". Disney: The Ultimate Visual Guide. Dorling Kindersley. p. 80. ISBN 978-0789488626.

- Ghez, Didier (2012). Walt's People – Volume 12: Talking Disney With the Artists Who Knew Him. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1477147894. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Koenig 1997, p. 154.

- Doty, Meriah (February 10, 2015). "Cruella de Vil's Comeback That Wasn't: See Long-Lost Sketches of Iconic Villain in 'The Rescuers' (Exclusive)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Beck, Jerry (October 28, 2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1556525919. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- "Madame Medusa". Disney Archives: Villains. Archived from the original on March 2, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- "The Rescuers DVD Fun Facts". Disney.go.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- Johnston, Ollie; Thomas, Frank (November 1, 1993). "The Rescuers". The Disney Villain. Disney Editions. pp. 156–63. ISBN 978-1562827922.

- Sharp, Margery (1959). The Rescuers. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

- Sharp, Margery (1962). Miss Bianca. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

- Koenig 1997, p. 155.

- "James MacDonald". Variety. February 17, 1991. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Thomas, Bob (March 7, 1997). "Carrying on the Tradition". Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules. Disney Editions. pp. 111–12. ISBN 978-0786862412.

- Deja, Andreas (May 20, 2014). "Deja View: Xerox". Blogger. Deja View. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Finch, Christopher (May 27, 1988). "Chapter 9: The End of an Era". The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms. Portland House. pp. 260. ISBN 978-0517664742.

- "Song Team Debuts". Playground Daily News. July 28, 1977. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Warda, Wayne (May 30, 1977). "It's a "Rocky" road to stardom, says Oscar-losing lyricist". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Siskel, Gene (July 6, 1977). "Orphan, teddy bear rescue Disney film". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Rescuers". Secondary Price Guide. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- "The Rescuers". Secondary Price Guide. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- "2008 Limited Edition-Orville with Bernard & Bianca". WDCC Duckman. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- Stevens, Mary (September 18, 1992). "`Rescuers` Leads Classic Kid Stuff". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Burger, Dennis. "The Rescuers Slated for 2012 Blu-ray Release! (Along with Over 30 Other Disney Flicks)". Technologytell. www.technologytell.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- Josh Katz (February 3, 2012). "Disney Teases 2012 Blu-ray Slate". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- "Photographic images of a topless woman can be spotted in The Rescuers". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- Davies, Jonathan (January 11, 1999). "Dis Calls in 'Rescuers' After Nude Images Found". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Howell, Peter (January 13, 1999). "Disney Knows the Net Never Blinks". The Toronto Star.

- Miller, D.M. (2001). "What Would Walt Do?". San Jose, CA: Writers Club Press. p. 96.

- White, Michael (January 8, 1999). "Disney Recalls 'The Rescuers' Video". Associated Press.

- "Disney recalls "sabotaged" video". The Independent (London). Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- King, Susan (June 22, 2012). "Disney's animated classic 'The Rescuers' marks 35th anniversary". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- Ludwig, Irving H. (January 3, 1979). "Disney: Never Forgetting Its Roots In Animation Medium". Variety. p. 30.

- "Box office for 1977". Box Office Story.

- Harmetz, Aljean (August 10, 1978). "Disney film far behind schedule". The New York Times. Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- "Top 100 Deutschland". Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Thomas, Bob (September 19, 1984). "Walt Disney Productions returns to animation". Lewison Daily Sun. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- "The Rescuers Release Summary". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Cawley, John. "The Rescuers". The Animated Films of Don Bluth. Cataroo.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- Champlin, Charles (July 3, 1977). "Animation: the Real Thing at Disney". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Canby, Vincent (July 7, 1977). "Disney's 'Rescuers,' Cheerful. Animation". The New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "The Rescuers Review". Movies.tvguide.com. September 3, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Ellen MacKay. "The Rescuers – Movie Review". Commonsensemedia.org. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Maltin, Leornard (2000). The Disney Films, p.265. JessieFilm Ltd., New York. ISBN 0-7868-8527-0. Quotations from this same source were used in the 1998 home video promotional trailer for the film found in the VHS release of Lady and the Tramp (1955) of the same year.

- "Feature Films". Frank and Ollie's Official Site. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- "The Rescuers – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- Jack G., Shaheen (2001). Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. Olive branch Press (an imprint of Interlink publishing group). p. 393. ISBN 1-56656-388-7.

- "Oscars Database". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

Bibliography

- Koenig, David (1997). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Irvine, California: Bonaventure Press. pp. 153–55. ISBN 978-0964060517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Rescuers |