Turkish bath

A Turkish bath or Hammam (Turkish: hamam, Arabic: حمّام, romanized: ḥammām) is a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world.[1] It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Ottoman Empire, as well as other regions and historical periods of the Muslim world. A variation on it as a method of cleansing and relaxation became popular during the Victorian era, and then spread through the British Empire and Western Europe. The buildings are similar to Roman thermae. Unlike Russian saunas (banya), which use steam, Turkish baths focus on water.

The particular bathing process roughly parallels ancient Roman bathing practices. It starts with relaxation in a room heated by a continuous flow of hot, dry air, allowing the bather to perspire freely. Bathers may then move to an even hotter room before they wash in cold water. After performing a full body wash and receiving a massage, bathers finally retire to the cooling-room for a period of relaxation.[2]

Unlike a hammam, Victorian Turkish baths use hot, dry air; in the Islamic hammam the air is often steamy. The bather in a Victorian Ottoman bath will often take a plunge in a cold pool after the hot rooms; the Islamic hammam usually does not have a pool unless the water is flowing from a spring. In the Islamic hammams, the bathers splash themselves with cold water.

The Victorian Turkish bath was described by Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Thudichum[3] in a lecture to the Royal Society of Medicine given in 1861, one year after the first such bath was opened in London:

The discovery that was lost and has been found again, is this, in the fewest possible words: The application of hot air to the human body. It is not wet air, nor moist air, nor vapoury air; it is not vapour in any shape or form whatever. It is an immersion of the whole body in hot common air.

Public bathing in the Islamic context

One of the Five Pillars of Islam is prayer. It is customary before praying to perform ablutions. The two Islamic forms of ablution are ghusl, a full-body cleansing, and wudu, a cleansing of the face, hands, and feet.[4] In the absence of water, cleansing with pure soil or sand is also permissible.[5] Mosques always provide a place to wash, but often hammams are located nearby for those who wish to perform deeper cleansing.[6]

Hammams, particularly in Morocco, evolved from their Roman roots to adapt to the needs of ritual purification according to Islam. For example, in most Roman-style hammams, one finds a cold pool for full submersion of the body. The style of bathing is less preferable in the Islamic faith, which finds bathing under running water without being fully submerged more appropriate.[6]

Al-Ghazali, a prominent Muslim theologian writing in the 11th century, wrote Revival of the Religious Sciences, a multi-volume work on dissecting the proper forms of conduct for many aspects of Muslim life and death. One of the volumes, entitled The Mysteries of Purity, details the proper technique for performing ablutions before prayer and the major ablution (ghusl) after anything which renders it necessary, such as the emission of semen.[7] For al-Ghazali, the hammam is a primarily male experience, and he cautions that women are to enter the hammam only after childbirth or illness. Even then al-Gazali finds it admissible for men to prohibit their wives or sisters from using the hammam. The major point of contention surrounding hammams in al-Ghazali's estimation is nakedness. In his work he warns that overt nakedness is to be avoided. "… he should shield it from the sight of others and second, guard against the touch of others."[8] He focuses extensively in his writing on the avoidance of touching the penis during bathing and after urination. He writes that nakedness is decent only when the area between the knees and the lower stomach of a man are hidden. For women, exposure of only the face and palms is appropriate. According to al-Gazali, the prevalence of nakedness in the hammam could incite indecent thoughts or behaviours and so it is a controversial space.[9] Ritual ablution is also required before or after sexual intercourse.[10] Knowing that, May Telmissany, a professor at the University of Ottawa, argues that the image of a hyper-sexualised woman leaving the hammam is an Orientalist perspective that sees leaving or attending the hammam as a sign of pre-eminent sexual behaviour.[11]

Social function: gendered social space

Arab hammams are gendered spaces where being a woman or a man can make someone included or a representative of the "other" respectively. Therefore, they represent a very special departure from the public sphere in which one is physically exposed amongst other women or men. This declaration of sexuality merely by being nude makes hammams a site of gendered expression. One exception to this gender segregation is the presence of young boys who often accompany their mothers until they grow old enough to necessitate attending the male hammam with their fathers.[12] The separation from the women’s hammam and entrance to the male hammam usually occurs at the age of 5 or 6.[10]

As a primarily female space, women's hammams play a special role in society. Valerie Staats finds that the women's hammams of Morocco serve as a social space where traditional and modern women from urban and rural areas of the country come together, regardless of their religiosity, to bathe and socialise.[13] While al-Ghazali and other Islamic intellectuals may have stipulated certain regulations for bathing, the regulations, being outdated and fundamental, are not usually upheld in the everyday interactions of Moroccans in the hammam. Staats argues that hammams are places where women can feel more at ease than they feel in many other public interactions.[14] In addition, in his work "Sexuality in Islam," Abdelwahab Bouhiba notes that some historians found evidence of hammams as spaces for sexual expression among women, which they believed was a result of the universality of nudity in these spaces.[15]

Massage

Massage in Turkish baths involves not just vigorous muscle kneading, but also joint cracking, "not so much a tender working of the flesh as a pummelling, a cracking of joints, a twisting of limbs...".[16][17]

The Turkish bath in art and in Western perspective

Arab hammams in general are not widely researched among Western scholars. In the writings that exist, the hammam is often portrayed as a place of sexual looseness, disinhibition and mystery. These Orientalist ideas paint the Arab "other" as mystical and sensuous, lacking morality in comparison to their Western counterparts.[18]

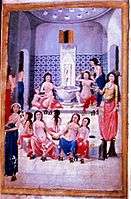

A famous painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Le Bain Turc ("The Turkish Bath"), depicts these spaces as magical and sexual. There are several women touching themselves or one another sensually while some dance to music played by the woman in the centre of the painting.

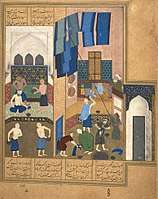

Bath house scene by Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, 1495

Bath house scene by Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, 1495 Women's bath, illustration from Husein Fâzıl-i Enderuni's Zanan-Name, 18th century

Women's bath, illustration from Husein Fâzıl-i Enderuni's Zanan-Name, 18th century Le Hamam, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1870

Le Hamam, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1870 Baigneuses, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, c. 1889

Baigneuses, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, c. 1889 Après le bain, by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Après le bain, by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Architecture

The hammam combines the functionality and the structural elements of its predecessors in Anatolia, the Roman thermae and baths, with Islamic and probably Central Asian Turkic tradition of steam bathing, ritual cleansing and respect of water [19] From the 11th century, The Seljuk Empire began to proliferate in Anatolia in lands conquered from the Eastern Romans leading eventually to the complete conquest of the remnants of the old empire in the 15th century. During those centuries of war, peace, alliance, trade and competition, the several cultures (Eastern Roman, Islamic Persian and Turkic ) had tremendous influence on each other. Moving beyond the reuse of the Greek and Roman baths (for example Byzantine Bath (Thessaloniki)), new bath were constructed as annex buildings of mosques, the complexes of which were community centres as well as houses of worship.

The Ottomans became prolific patrons of baths, building a number of ambitious structures, particularly in Constantinople, whose Greek inhabitants had retained a strong Eastern Roman bath culture (see Baths of Zeuxippus).[20] The monumental baths designed by Renaissance Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan (1489–1588), such as the Çemberlitaş Hamamı, the bath in the complex of the Süleymaniye Mosque, and the bath of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne were particularly influential.

Like its Roman predecessor, a typical hamam consists of three basic, interconnected rooms: the sıcaklık (or hararet – in Latin, caldarium), which is the hot room; the warm room (tepidarium), which is the intermediate room; and the soğukluk, which is the cool room (frigidarium). The main evolutionary change between Roman baths and Turkish baths concerned the cool room. The Roman frigidarium included a quite cold water pool in which patrons would immerse themselves before moving on to the warmer rooms. Medieval Muslim customs put a high priority on cleanliness but preferred running water to immersion baths, so the cold water pool was dispensed with. Also, the sequence of rooms was revised so that people generally used the cool room after the warmer rooms and massages, rather than before. Whereas the Romans used it as preparation, the Ottomans used it for refreshment (drinks and snacks are served) and recovery.

The sıcaklık usually has a large dome decorated with small glass clerestory windows that create a half-light; in the center of the room is a large heated marble table (göbek taşı or navel stone) that the customers lie on, and niches with fountains in the corners. This room is for soaking up steam and getting scrub massages. The warm room is used for washing with soap and water and the soğukluk is to relax, dress, have a refreshing drink, sometimes tea, and, where available, a nap in a private cubicle after the massage. A few of the hamams in Istanbul also contain mikvehs, ritual cleansing baths for Jewish women.

The hamam, like its precursors, is not exclusive to men. Hamam complexes usually contain separate quarters for men and women; or males and females are admitted at separate times. Because they were social centers as well as baths, hamams became numerous during the time of the Ottoman Empire and were built in almost every Ottoman city. On many occasions they became places of entertainment (such as dancing and food, especially in the women's quarters) and ceremonies, such as before weddings, high-holidays, celebrating newborns, beauty trips.

Several accessories from Roman times survive in modern hamams, such as the peştemal (a special cloth of silk and/or cotton to cover the body, like a pareo), nalın (wooden clogs that prevent slipping on the wet floor, or mother-of-pearl), kese (a rough mitt for massage), and sometimes jewel boxes, gilded soap boxes, mirrors, henna bowls and perfume bottles.

Traditionally, the masseurs in the baths, tellak in Turkish, were young men who helped wash clients by soaping and scrubbing their bodies. After the defeat and dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, the role of tellak boys was filled by adult attendants.[21]

Famous examples

Arab world

Morocco

The ruins of the oldest known Islamic hammam in Morocco, dating back to the late 8th century, can be found in Volubilis. Public baths in Morocco are embedded into a social-cultural history that has played a significant role in both urban and rural Moroccan cities. These public spaces for cleansing grew rapidly as Islamic cultures assimilated to the bathing techniques widely used during the Roman and Byzantine periods.[6] The structure of Islamic hammams in the Arab world varies from that of what has been termed the traditional “Roman bath.” Additionally, since Morocco (unlike Egypt or Syria) was never under Ottoman rule, its baths are not technically Turkish although guide books might refer to them as such. This misnomer can be due in part to the Arabic use of the word hammam, which translates to “bathroom” or “public bath place” and can be used to refer to all baths, including those in the Turkish and Roman design.

Hammams in Morocco are often close to mosques to facilitate the performance of ablutions. Because of their private nature (overt nudity and gender separation), their entrances are often discreet and the building's façade is typically windowless. Vestiges of Roman bathing styles can be seen in the manifestation of the three-room structure, which was widespread during the Roman/Byzantine period.

In Morocco, hammams are typically smaller than Roman/Byzantine baths. While it may be difficult to identify a hammam from the face of the structure, the hammam roof betrays itself with its series of characteristic domes that indicate chambers in the building.[22] Hammams often occupy irregularly shaped plots to fit them seamlessly into the city’s design. They are significant sites of culture and socialisation as they are integrated into medina, or city, life in proximity to mosques, madrassas (schools) and aswaq (markets). Magda Sibley, an expert on Islamic public baths writes that second to mosques, many specialists in Islamic architecture and urbanism find the hammam to be the most significant building in Islamic medinas.[22]

Syria

An old legendary story says that Damascus once had 365 hammams or "Turkish baths", one for each day of the year. For centuries, hammams were an integral part of community life, with some 50 hammams surviving in Damascus until the 1950s. As of 2012, however, with the growth of modernisation programmes and home bathrooms, fewer than 20 Damascene working hamams had survived.[23] According to many historians, the northern city of Aleppo was home to 177 hammams during the medieval period until the Mongol invasion when many vital structures in the city were destroyed. Until 1970, around 40 hammams were still operating in the city. Nowadays, roughly 18 hammams are operating in the Ancient part of the city.[24]

- Hammam al-Sultan built in 1211 by Az-Zahir Ghazi.

- Hammam al-Nahhaseen built during the 12th century near Khan al-Nahhaseen.

- Hammam al-Bayadah of the Mamluk era built in 1450.

- Hammam Yalbugha built in 1491 by the Emir of Aleppo Saif ad-Din Yalbugha al-Naseri.[25]

- Hammam al-Jawhary, Gammam Azdemir, Hammam Bahram Pasha, Hammam Bab al-Ahmar, etc.

Egypt

Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, and the hamams of Cairo and other major cities like Alexandria are evidence of the unique Ottoman legacy. There used to be as many as 300 hamams in Cairo. As of 2012, only seven remain. Two of them, located in the El Hussien and Khan el-Khalili districts are closed.

Turkey

There are many historical hammams in Istanbul. Ağa hamamı, built in 1454, is on Turnacıbaşı Street near Taksim Square. The Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı or Ayasofya Haseki Hamamı was commissioned by Suleiman I's consort, Hürrem Sultan, and constructed by Mimar Sinan during the 16th century. It was built on the site of the historical Baths of Zeuxippus for the religious community of the nearby Hagia Sophia. Süleymaniye Hamam is situated on a hill facing the Golden Horn. It was built in 1557 by Mimar Sinan; it was named after Süleyman the Magnificent. It is part of the complex of the Suleymaniye Mosque. Çemberlitaş Hamamı on Divanyolu Street in the Çemberlitaş neighbourhood was constructed by Mimar Sinan in 1584. The Cağaloğlu Hamam, finished in 1741, is the last hamam to be built in the Ottoman Empire.

Outside the capital, Tarihi Karataş Hoşgör Hamamı, built in 1855, is on Karataş in the Konak neighbourhood of Izmir.

Greece and Cyprus

In Thessaloniki, Bey Hamam was built in 1444 by sultan Murad II. It is a double bath, for men and women. The baths remained in use, under the name "Baths of Paradise", until 1968. Pasha Hamam was built in 1520–1530, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, and operated until 1981 under the name "Fenix Baths". Restored, it now houses archeological findings from construction on the Thessaloniki metro.

The Hamam Omerye Baths in Nicosia date to the 14th century. Built as an Augustinian church of St. Mary of stone, with small domes, they date to the Frankish and Venetian period, like the city walls. In 1571, the ruler Mustafa Bilal Geldosh Pasha converted the church into a mosque, believing that it was where the Khalifa Umar rested during his visit to Lefkosia. Most of the building was destroyed by Ottoman artillery although the door of the main entrance belongs to the 14th century Lusignan building, and remains of a later Renaissance phase can be seen at the north-eastern side of the monument. In 2003, the [EU] funded a bi-communal UNDP/UNOPS project, "Partnership for the Future", in collaboration with Nicosia Municipality and Nicosia Master Plan. The Büyük Hammam dates to the 14th century.

Hungary

Budapest, the City of Spas has four working Turkish baths, all from the 16th century and open to the public: Rudas Baths, Király Baths, Rácz Thermal Bath, and Császár Spa Bath (reopened to the public since December 2012).

Hammam at the Citadel of Aleppo, c. 1200

Hammam at the Citadel of Aleppo, c. 1200 Hamam hot chamber in the Bey Hamam in Thessaloniki, built 1444

Hamam hot chamber in the Bey Hamam in Thessaloniki, built 1444

Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı, 16th century

Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı, 16th century Fountain in the Ibrahim Sirag el-Din hammam, Samannūd, Egypt

Fountain in the Ibrahim Sirag el-Din hammam, Samannūd, Egypt- Turkish Bath, interior

Istanbul, a hotel hamam

Istanbul, a hotel hamam

India

Delhi, Hyderabad and Bhopal have multiple working Turkish Baths, which were started during the Mughal period in the early 16th century.[26][27][28][29][30] Two prominent examples include the Hammam-e-Qadimi and Hammam-e-Lal Qila.[31]

Pakistan

Lahore's Shahi Hammam or Royal Bath House, located in the Walled City of Lahore, is one of the best preserved examples of a Mughal era Hamam. The Hamam was built in 1634 by the Mughal Governor of Lahore Hakim Ilmuddin Ansari, during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan.

Introduction to Western Europe

By the mid 19th century, baths and wash houses in Britain took several forms. Turkish baths were introduced by David Urquhart, diplomat and sometime Member of Parliament for Stafford, who for political and personal reasons wished to popularise Turkish culture. In 1850, he wrote The Pillars of Hercules, a book about his travels in 1848 through Spain and Morocco. He described the system of dry hot-air baths used there and in the Ottoman Empire, which had changed little since Roman times. In 1856, Richard Barter read Urquhart's book and worked with him to construct a bath. Although this was not a success, Barter persevered and later that year opened the first modern Turkish bath at St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment near Blarney, County Cork, Ireland.[32] The following year, the first public bath of its type to be built in mainland Britain since Roman times was opened in Manchester, and the idea spread rapidly. It reached London in July 1860, when Roger Evans, a member of one of Urquhart's Foreign Affairs Committees, opened a Turkish bath at 5 Bell Street, near Marble Arch.

During the following 150 years, over 600 Turkish baths opened in the country, including those built by municipal authorities as part of swimming pool complexes, taking advantage of the fact that water-heating boilers were already on site.

Similar baths opened in other parts of the British Empire. Dr. John Le Gay Brereton, who had given medical advice to bathers in a Foreign Affairs Committee-owned Turkish bath in Bradford, travelled to Sydney, Australia, and opened a Turkish bath there on Spring Street in 1859, even before such baths had reached London.[33] Canada had one by 1869, and the first in New Zealand was opened in 1874.

Urquhart's influence was also felt outside the Empire when in 1861, Dr Charles H Shepard opened the first Turkish baths in the United States at 63 Columbia Street, Brooklyn Heights, New York City, most probably on 3 October 1863.[34] Before that, the United States, like many other places, had several Russian baths, one of the first being that opened in 1861 by M. Hlasko at his "natatorium" at 219 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia.[35] In Germany in 1877, Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden opened the Friedrichsbad Roman-Irish baths in Baden-Baden. This was also based on the Victorian Turkish bath, and is still open today.[36]

As of September 2013 there were just twelve Victorian or Victorian-style Turkish baths remaining open in Britain,[37] but hot-air baths still thrive in the form of the Russian steambath and the Finnish sauna. A few of Britain's Turkish baths, while retaining their original decorative style, are now used for other purposes, such as day spas, restaurants, events venues[38] and business centres.[39]

See also

- Gellért Baths

- Jjimjilbang, the Korean equivalent

- Onsen and sentō, the Japanese equivalents

- Steam shower

- Hydrotherapy

Notes and references

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Bath". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- "Hammam" by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Jahan-i Tibb, Volume 7, Number 1, July–September 2005, Central Council for Research in Unani Medicine, Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy, pages 12–17.

- "The Turkish bath" by J L W Thudichum, Transactions of the Royal Medical Society, 1861, page 40.

- Rahim, Habibeh (2001). "Understanding Islam". The Furrow. 52 (12): 670–674.

- Reinhart, Kevin (1990). "Impurity/No Danger". History of Religions. 30 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1086/463212.

- Sibley, Magda. "The Historic Hammams of Damascus and Fez: Lessons of Sustainability and Future Developments". The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture.

- Ghazali, Abu Hammid (1975). The Mysteries of Purity: Being a Translation with Notes of the Kitāb Asrār Al-ṭahārah of Al-Ghazzāli's Iḥyāʼ ʻulūm Al-dīn. Lahore: Muhammad Ashraf.

- Ghazali, Abu Hammid (1975). The Mysteries of Purity: Being a Translation with Notes of the Kitāb Asrār Al-ṭahārah of Al-Ghazzāli's Iḥyāʼ ʻulūm Al-dīn. Lahore: Muhammad Ashraf. p. 51.

- Bouhdiba, Abdelwahab (1985). Sexuality in Islam. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 62.

- Joseph, Suad; Afsaneh Najmabadi (2003). Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures. Leiden: Brill.

- Nkrumah, Gamal (23 July 2009). "Tales from the Hammam". Al-Ahram Weekly.

- Kilito, Abdelfettah; Patricia Geesey (1992). "Architecture and the Sacred: A Season in the Hamam". Research in African Literatures. 23 (2): 203–208.

- Staats, Valerie (1994). "Ritual, Strategy, or Convention: Social Meanings in the Traditional Women's Baths in Morocco". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 14 (3): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3346678. JSTOR 3346678.

- Staats, Valerie (1994). "Ritual, Strategy, or Convention: Social Meanings in the Traditional Women's Baths in Morocco". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 14 (3): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3346678. JSTOR 3346678.

- Bouhdiba, Abdelwahab (1985). Sexuality in Islam. Saqi Books. p. 167.

- Richard Boggs, Hammaming in the Sham: A Journey Through the Turkish Baths of Damascus, Aleppo and Beyond, 2012, ISBN 1859643256, p. 161

- Alexander Russell, The Natural History of Aleppo, 1756, 2nd edition, 1794, p. 134-5

- Staats, Valerie (1994). "Ritual, Strategy, or Convention: Social Meanings in the Traditional Women's Baths in Morocco". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 14 (3): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3346678. JSTOR 3346678.

- The Guide of Turkish Baths.

- Hamams in Islamic tradition (cyberbohemia.com) Archived 14 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- (Yilmazkaya & Deniz 2005) discusses occasional licentious activity

- Sibley, Magda; Fodil Fadli (2009). "Hammams in North Africa: An Architectural Study of Sustainability Concepts in a Historical Traditional Building". 26th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture.

- Hammaming in the Sham: A Journey through the Turkish Baths of Damascus, Aleppo and Beyond, Richard Boggs, Garnet Publishing Ltd.

- Alepo hammams

- Carter, Terry; Dunston, Lara; Humphreys, Andrew (2004). Syria & Lebanon. Lonely Planet. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-86450-333-3.

Hammam yalbougha.

- "Turkish bath centre defunct at Nizamia general hospital". siasat.com. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Where are those Turkish baths?". The Times of India. 11 June 2004. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Centre keen on hammam". The Times of India. 27 November 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Hyderabad Attractions". The New York Times. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Syed Zillur Rahman, Hammam – Past and Present, Newsletter of Ibn Sina Academy 2012, Volume 12 No 1: 10–16

- Gianani, Kareena (22 June 2016). "Bhopal's 300-Year-Old Hidden Hammam". National Geographic. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Shifrin, Malcolm (3 October 2008), "St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment, Blarney, Co. Cork", Victorian Turkish Baths: Their origin, development, and gradual decline, retrieved 12 December 2009

- Shifrin, Malcolm (2015). Victorian Turkish Baths. London: Historic England. pp. 51–2.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 3 October 1863

- To Philadelphians on behalf of the Natatorium & Physical Institute. 1860. p. 11. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Roman-Irish baths, Baden-Baden. Retrieved 16 December 2017

- "Victorian-style Turkish baths still open in the UK". Victorianturkishbath.org. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Victorian bath house

- Ashton Old Baths. Retrieved 16 December 2017

Primary bibliography

- Allsop, Robert Owen (1890), The Turkish bath: its design and construction, Spon (Deals only with the Victorian Turkish bath)

- Cosgrove, J. J. (2001) [1913], Design of the Turkish bath, Books for Business, ISBN 978-0-89499-078-6 (Deals only with the Victorian Turkish bath)

- Gazali, Münif Fehim (2001), Book of Shehzade, Dönence, ISBN 978-975-7054-17-7

- Shifrin, Malcolm (2015), Victorian Turkish baths, Swindon: Historic England, ISBN 978-1-84802-230-0

- Toledano, Ehud R. (2003), State and Society in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Egypt, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53453-6

- Yilmazkaya, Orhan; Deniz, Ogurlu (2005), A light onto a tradition and culture: Turkish baths: a guide to the historic Turkish baths of Istanbul (2 ed.), Çitlembik, ISBN 978-975-6663-80-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammams. |

- Michael Palin at Turkish baths in Istanbul - BBC (From Pole to Pole) uploaded by BBC Worldwide to YouTube

- The Turkish Bath Experience