Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian period, and its later half overlaps with the first part of the Belle Époque era of Continental Europe. In terms of moral sensibilities and political reforms, this period began with the passage of the Reform Act 1832. There was a strong religious drive for higher moral standards led by the nonconformist churches, such as the Methodists, and the Evangelical wing of the established Church of England. Britain's relations with the other Great Powers were driven by the colonial antagonism of the Great Game with Russia, climaxing during the Crimean War; a Pax Britannica of international free trade was maintained by the country's naval and industrial supremacy. Britain embarked on global imperial expansion, particularly in Asia and Africa, which made the British Empire the largest empire in history. National self-confidence peaked.[1]

| 1837–1901 | |

Queen Victoria by Bassano (1887) | |

| Preceded by | Regency era |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Edwardian era |

| Monarch(s) | Victoria |

| Leader(s) | |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United Kingdom |

.jpg) |

|

Topics |

|

|

| Periods in English history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Scotland |

|

|

|

|

By Region |

|

|

Ideologically, the Victorian era witnessed resistance to the rationalism that defined the Georgian period and an increasing turn towards romanticism and even mysticism with regard to religion, social values, and arts.[2]

Domestically, the political agenda was increasingly liberal, with a number of shifts in the direction of gradual political reform, social reform, and the widening of the franchise. There were unprecedented demographic changes: the population of England and Wales almost doubled from 16.8 million in 1851 to 30.5 million in 1901,[3] and Scotland's population also rose rapidly, from 2.8 million in 1851 to 4.4 million in 1901. However, Ireland's population decreased sharply, from 8.2 million in 1841 to less than 4.5 million in 1901, mostly due to emigration and the Great Famine.[4] Between 1837 and 1901 about 15 million emigrated from Great Britain, mostly to the United States, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia.[5]

The two main political parties during the era remained the Whigs/Liberals and the Conservatives; by its end, the Labour Party had formed as a distinct political entity. These parties were led by such prominent statesmen as Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Lord Derby, Lord Palmerston, Benjamin Disraeli, William Gladstone, and Lord Salisbury. The unsolved problems relating to Irish Home Rule played a great part in politics in the later Victorian era, particularly in view of Gladstone's determination to achieve a political settlement in Ireland.

Terminology and periodisation

In the strictest sense, the Victorian era covers the duration of Victoria's reign as Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, from her accession on 20 June 1837—after the death of her uncle, William IV—until her death on 22 January 1901, after which she was succeeded by her eldest son, Edward VII. Her reign lasted for 63 years and seven months, a longer period than any of her predecessors. The term 'Victorian' was in contemporaneous usage to describe the era.[6] The era has also been understood in a more extensive sense as a period that possessed sensibilities and characteristics distinct from the periods adjacent to it, in which case it is sometimes dated to begin before Victoria's accession—typically from the passage of or agitation for (during the 1830s) the Reform Act 1832, which introduced a wide-ranging change to the electoral system of England and Wales. Definitions that purport a distinct sensibility or politics to the era have also created scepticism about the worth of the label "Victorian", though there have also been defences of it.[7]

Michael Sadleir was insistent that "in truth, the Victorian period is three periods, and not one".[8] He distinguished early Victorianism – the socially and politically unsettled period from 1837 to 1850[9] – and late Victorianism (from 1880 onwards), with its new waves of aestheticism and imperialism,[10] from the Victorian heyday: mid-Victorianism, 1851 to 1879. He saw the latter period as characterized by a distinctive mixture of prosperity, domestic prudery, and complacency[11] – what G. M. Trevelyan similarly called the "mid-Victorian decades of quiet politics and roaring prosperity".[12]

Political and diplomatic history

Early

In 1832, after much political agitation, the Reform Act was passed on the third attempt. The Act abolished many borough seats and created others in their place, as well as expanding the franchise in England and Wales (a Scottish Reform Act and Irish Reform Act were passed separately). Minor reforms followed in 1835 and 1836.

.jpg)

On 20 June 1837, Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom on the death of her uncle, William IV. Her government was led by the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne, but within two years he had resigned, and the Tory politician Sir Robert Peel attempted to form a new ministry. In the same year, a seizure of British opium exports to China prompted the First Opium War against the Qing dynasty, and British imperial India initiated the First Anglo-Afghan War—one of the first major conflicts of the Great Game between Britain and Russia.[13]

In 1840, Queen Victoria married her German cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield. It proved a very happy marriage, whose children were much sought after by royal families across Europe. In 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi established British sovereignty over New Zealand. The signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 ended the First Opium War and gave Britain control over Hong Kong Island. However, a disastrous retreat from Kabul in the same year led to the annihilation of a British army column in Afghanistan. In 1845, the Great Famine began to cause mass starvation, disease and death in Ireland, sparking large-scale emigration;[14] To allow more cheap food into Ireland, the Peel government repealed the Corn Laws. Peel was replaced by the Whig ministry of Lord John Russell.[15]

In 1853, Britain fought alongside France in the Crimean War against Russia. The goal was to ensure that Russia could not benefit from the declining status of the Ottoman Empire,[16] a strategic consideration known as the Eastern Question. The conflict marked a rare breach in the Pax Britannica, the period of relative peace (1815–1914) that existed among the Great Powers of the time, and especially in Britain's interaction with them. On its conclusion in 1856 with the Treaty of Paris, Russia was prohibited from hosting a military presence in Crimea. In October of the same year, the Second Opium War saw Britain overpower the Qing dynasty in China.

During 1857–58, an uprising by sepoys against the East India Company was suppressed, an event that led to the end of Company rule in India and the transferral of administration to direct rule by the British government. The princely states were not affected and remained under British guidance.[17]

Middle

In 1861, Prince Albert died.[13] In 1867, the second Reform Act was passed, expanding the franchise, and the British North America Act consolidated the country's possessions in that region into a Canadian Confederation.[18]

In 1878, Britain was a plenipotentiary at the Treaty of Berlin, which gave de jure recognition to the independent states of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro.

Society and culture

Evangelicals, utilitarians, and reform

The central feature of Victorian-era politics is the search for reform and improvement, including both the individual personality and society.[19] Three powerful forces were at work. First was the rapid rise of the middle class, in large part displacing the complete control long exercised by the aristocracy. Respectability was their code—a businessman had to be trusted and must avoid reckless gambling and heavy drinking. Second, the spiritual reform closely linked to evangelical Christianity, including both the Nonconformist sects, such as the Methodists, and especially the evangelical or Low Church element in the established Church of England, typified by Lord Shaftesbury (1801–1885).[20] It imposed fresh moralistic values on society, such as Sabbath observance, responsibility, widespread charity, discipline in the home, and self-examination for the smallest faults and needs of improvement. Starting with the anti-slavery movement of the 1790s, the evangelical moralizers developed highly effective techniques of enhancing the moral sensibilities of all family members and reaching the public at large through intense, very well organized agitation and propaganda. They focused on exciting a personal revulsion against social evils and personal misbehavior.[21] Asa Briggs points out, "There were as many treatises on 'domestic economy' in mid-Victorian England as on political economy"[22]

The third effect came from the philosophical utilitarians, led by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), James Mill (1773–1836) and his son John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). They were not moralistic but scientific. Their movement, often called "Philosophic Radicalism," fashioned a formula for promoting the goal of "progress" using scientific rationality, and businesslike efficiency, to identify, measure, and discover solutions to social problems. The formula was an inquiry, legislation, execution, inspection, and report.[23] In public affairs, their leading exponent was Edwin Chadwick (1800–1890). Evangelicals and utilitarians shared a basic middle-class ethic of responsibility and formed a political alliance. The result was an irresistible force for reform.[24]

Social reforms focused on ending slavery, removing the slavery-like burdens on women and children, and reforming the police to prevent crime, rather than emphasizing the very harsh punishment of criminals. Even more important were political reforms, especially the lifting of disabilities on nonconformists and Roman Catholics, and above all, the reform of Parliament and elections to introduce democracy and replace the old system whereby senior aristocrats controlled dozens of seats in parliament.[25]

Religion

Religion was a battleground during this era, with the Nonconformists fighting bitterly against the established status of the Church of England, especially regarding education and access to universities and public office. Penalties on Roman Catholics were mostly removed. The Vatican restored the English Catholic bishoprics in 1850 and numbers grew through conversions and immigration from Ireland.[26] Secularism and doubts about the accuracy of the Old Testament grew as the scientific outlooked rapidly gained ground among the better educated. Walter E. Houghton argues, "Perhaps the most important development in 19th-century intellectual history was the extension of scientific assumptions and methods from the physical world to the whole life of man."[27]

Status of Nonconformist churches

Nonconformist conscience describes the moral sensibility of the Nonconformist churches—those which dissent from the established Church of England—that influenced British politics in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[28][29] In the 1851 census of church attendance, non-conformists who went to chapel comprised half the attendance of Sunday services.[30] Nonconformists were focused in the fast-growing urban middle class.[31] The two categories of this group were in addition to the evangelicals or "Low Church" element in the Church of England: "Old Dissenters," dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, included Baptists, Congregationalists, Quakers, Unitarians, and Presbyterians outside Scotland; "New Dissenters" emerged in the 18th century and were mainly Methodists. The "Nonconformist conscience" of the Old group emphasized religious freedom and equality, the pursuit of justice, and opposition to discrimination, compulsion, and coercion. The New Dissenters (and also the Anglican evangelicals) stressed personal morality issues, including sexuality, temperance, family values, and Sabbath-keeping. Both factions were politically active, but until the mid-19th century, the Old group supported mostly Whigs and Liberals in politics, while the New—like most Anglicans—generally supported Conservatives. In the late 19th century, the New Dissenters mostly switched to the Liberal Party. The result was a merging of the two groups, strengthening their great weight as a political pressure group. They joined together on new issues especially regarding schools and temperance, with the latter of special interest to Methodists.[32][33] By 1914 the linkage was weakening and by the 1920s it was virtually dead.[34]

Parliament had long imposed a series of political disabilities on Nonconformists outside Scotland. They could not hold most public offices, they had to pay local taxes to the Anglican church, be married by Anglican ministers, and be denied attendance at Oxford or degrees at Cambridge. Dissenters demanded the removal of political and civil disabilities that applied to them (especially those in the Test and Corporation Acts). The Anglican establishment strongly resisted until 1828.[35] Dissenters organized into a political pressure group and succeeded in 1828 in the repeal of some restrictions. It was a major achievement for an outside group, but the Dissenters were not finished and the early Victorian period saw them even more active and successful in eliminating their grievances.[36] Next on the agenda was the matter of church rates, which were local taxes at the parish level for the support of the parish church building in England and Wales. Only buildings of the established church received the tax money. Civil disobedience was attempted but was met with the seizure of personal property and even imprisonment. The compulsory factor was finally abolished in 1868 by William Ewart Gladstone, and payment was made voluntary.[37] While Gladstone was a moralistic evangelical inside the Church of England, he had strong support in the Nonconformist community.[38][39] The Marriage Act 1836 allowed local government registrars to handle marriages. Nonconformist ministers in their chapels were allowed to marry couples if a registrar was present. Also in 1836, civil registration of births, deaths, and marriages was taken from the hands of local parish officials and given to local government registrars. Burial of the dead was a more troubling problem, for urban chapels had no graveyards, and Nonconformists sought to use the traditional graveyards controlled by the established church. The Burial Laws Amendment Act 1880 finally allowed that.[40]

Oxford University required students seeking admission to subscribe to the 39 Articles of the Church of England. Cambridge required that for a diploma. The two ancient universities opposed giving a charter to the new University of London in the 1830s because it had no such restriction. The university, nevertheless, was established in 1837, and by the 1850s Oxford dropped its restrictions. In 1871 Gladstone sponsored the Universities Tests Act 1871 that provided full access to degrees and fellowships. Nonconformists (especially Unitarians and Presbyterians) played major roles in founding new universities in the late 19th century at Manchester, as well as Birmingham, Liverpool and Leeds.[41]

Agnostics and freethinkers

The abstract theological or philosophical doctrine of agnosticism, whereby it is theoretically impossible to prove whether or not God exists, suddenly became a popular issue around 1869, when T. H. Huxley coined the term. It was much discussed for several decades, and had its journal edited by William Stewart Ross (1844–1906) the Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review. Interest petered out by the 1890s, and when Ross died the Journal soon closed. Ross championed agnosticism in opposition not so much to Christianity, but to atheism, as expounded by Charles Bradlaugh[42] The term "atheism" never became popular. Blasphemy laws meant that promoting atheism could be a crime and was vigorously prosecuted.[43] Charles Southwell was among the editors of an explicitly atheistic periodical, Oracle of Reason, or Philosophy Vindicated, who were imprisoned for blasphemy in the 1840s.[44]

Disbelievers call themselves "freethinkers" or "secularists". They included John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle, George Eliot and Matthew Arnold.[45] They were not necessarily hostile to Christianity, as Huxley repeatedly emphasized. The literary figures were caught in something of a trap – their business was writing and their theology said there was nothing for certain to write. They instead concentrated on the argument that it was not necessary to believe in God to behave in moral fashion.[46] The scientists, on the other hand, paid less attention to theology and more attention to the exciting issues raised by Charles Darwin in terms of evolution. The proof of God's existence that said he had to exist to have a marvelously complex world was no longer satisfactory when biology demonstrated that complexity could arise through evolution.[47]

Family and gender roles

The centrality of the family was a dominant feature for all classes. Worriers repeatedly detected threats that had to be dealt with: working wives, overpaid youths, harsh factory conditions, bad housing, poor sanitation, excessive drinking, and religious decline. The licentiousness so characteristic of the upper class of the late 18th and early 19th centuries dissipated. The home became a refuge from the harsh world; middle-class wives sheltered their husbands from the tedium of domestic affairs. The number of children shrank, allowing much more attention to be paid to each child. Extended families were less common, as the nuclear family became both the ideal and the reality.[48]

The emerging middle-class norm for women was separate spheres, whereby women avoid the public sphere – the domain of politics, paid work, commerce, and public speaking. Instead, they should dominate in the realm of domestic life, focused on the care of the family, the husband, the children, the household, religion, and moral behavior.[49] Religiosity was in the female sphere, and the Nonconformist churches offered new roles that women eagerly entered. They taught in Sunday schools, visited the poor and sick, distributed tracts, engaged in fundraising, supported missionaries, led Methodist class meetings, prayed with other women, and a few were allowed to preach to mixed audiences.[50]

The long 1854 poem The Angel in the House by Coventry Patmore (1823–1896) exemplified the idealized Victorian woman who is angelically pure and devoted to her family and home. The poem was not a pure invention but reflected the emerging legal economic social, cultural, religious and moral values of the Victorian middle-class. Legally women had limited rights to their bodies, the family property, or their children. The recognized identities were those of daughter, wife, mother, and widow. Rapid growth and prosperity meant that fewer women had to find paid employment, and even when the husband owned a shop or small business, the wife's participation was less necessary. Meanwhile, the home sphere grew dramatically in size; women spent the money and decided on the furniture, clothing, food, schooling, and outward appearance the family would make. Patmore's model was widely copied – by Charles Dickens, for example.[51] Literary critics of the time suggested that superior feminine qualities of delicacy, sensitivity, sympathy, and sharp observation gave women novelists a superior insight into stories about home family and love. This made their work highly attractive to the middle-class women who bought the novels and the serialized versions that appeared in many magazines. However, a few early feminists called for aspirations beyond the home. By the end of the century, the "New Woman" was riding a bicycle, wearing bloomers, signing petitions, supporting worldwide mission activities, and talking about the vote.[52]

Education

The era saw a reform and renaissance of public schools, inspired by Thomas Arnold at Rugby. The public school became a model for gentlemen and public service.[53]

Literature and arts

In prose, the novel rose from a position of relative neglect during the 1830s to become the leading literary genre by the end of the era.[6][54] In the 1830s and 1840s, the social novel (also "Condition-of-England novels") responded to the social, political and economic upheaval associated with industrialisation. Though it remained influential throughout the period, there was a notable resurgence of Gothic fiction in the fin de siècle, such as in Robert Louis Stevenson's novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891).

Entertainment

Popular forms of entertainment varied by social class. Victorian Britain, like the periods before it, was interested in literature (see Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë, Robert Louis Stevenson and William Makepeace Thackeray), theatre and the arts (see Aesthetic movement and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood), and music, drama, and opera were widely attended. Michael Balfe was the most popular British grand opera composer of the period, while the most popular musical theatre was a series of fourteen comic operas by Gilbert and Sullivan, although there was also musical burlesque and the beginning of Edwardian musical comedy in the 1890s. Drama ranged from low comedy to Shakespeare (see Henry Irving). Melodrama was a particularly widespread and influential theatrical genre. There were, however, other forms of entertainment. Gentlemen went to dining clubs, like the Beefsteak Club or the Savage Club. Gambling at cards in establishments popularly called casinos was wildly popular during the period: so much so that evangelical and reform movements specifically targeted such establishments in their efforts to stop gambling, drinking, and prostitution.[55]

Brass bands and 'The Bandstand' became popular in the Victorian era. The bandstand was a simple construction that not only created an ornamental focal point but also served acoustic requirements whilst providing shelter from the changeable British weather. It was common to hear the sound of a brass band whilst strolling through parklands. At this time musical recording was still very much a novelty.[56]

The Victorian era marked the golden age of the British circus.[57] Astley's Amphitheatre in Lambeth, London, featuring equestrian acts in a 42-foot wide circus ring, was the center of the 19th-century circus. The permanent structure sustained three fires but as an institution lasted a full century, with Andrew Ducrow and William Batty managing the theatre in the middle part of the century. William Batty would also build his 14,000-person arena, known commonly as Batty's Hippodrome, in Kensington Gardens, and draw crowds from the Crystal Palace Exhibition. Traveling circuses, like Pablo Fanque's, dominated the British provinces, Scotland, and Ireland (Fanque would enjoy fame again in the 20th century when John Lennon would buy an 1843 poster advertising his circus and adapt the lyrics for The Beatles song, Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!). Fanque also stands out as a black man who achieved great success and enjoyed great admiration among the British public only a few decades after Britain had abolished slavery.[58][58]

Another form of entertainment involved "spectacles" where paranormal events, such as mesmerism, communication with the dead (by way of mediumship or channeling), ghost conjuring and the like, were carried out to the delight of crowds and participants. Such activities were more popular at this time than in other periods of recent Western history.[59]

Natural history became increasingly an "amateur" activity. Particularly in Britain and the United States, this grew into specialist hobbies such as the study of birds, butterflies, seashells (malacology/conchology), beetles and wildflowers. Amateur collectors and natural history entrepreneurs played an important role in building the large natural history collections of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[60][61]

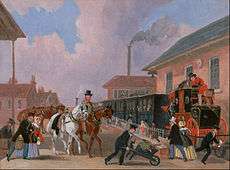

Middle-class Victorians used the train services to visit the seaside, helped by the Bank Holiday Act of 1871, which created many fixed holidays. Large numbers traveling to quiet fishing villages such as Worthing, Morecambe and Scarborough began turning them into major tourist centers, and people like Thomas Cook saw tourism and even overseas travel as viable businesses.[62]

Sport

The Victorian era saw the introduction and development of many modern sports.[63] Often originating in the public schools, they exemplified new ideals of manliness.[64] Cricket,[65] cycling, croquet, horse-riding, and many water activities are examples of some of the popular sports in the Victorian era.[66]

The modern game of tennis originated in Birmingham, England, between 1859 and 1865. The world's oldest tennis tournament, the Wimbledon championships, was first played in London in 1877. Britain was an active competitor in all the Olympic Games starting in 1896.

Economy, industry, and trade

.jpg)

Progress

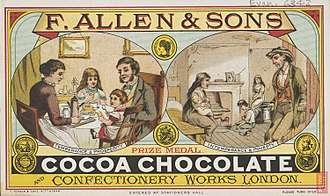

Historians have characterised the mid-Victorian era (1850–1870) as Britain's "Golden Years".[68] There was prosperity, as the national income per person grew by half. Much of the prosperity was due to the increasing industrialisation, especially in textiles and machinery, as well as to the worldwide network of trade and engineering that produced profits for British merchants, and exports from across the globe. There was peace abroad (apart from the short Crimean War, 1854–56), and social peace at home. Opposition to the new order melted away, says Porter. The Chartist movement peaked as a democratic movement among the working class in 1848; its leaders moved to other pursuits, such as trade unions and cooperative societies. The working class ignored foreign agitators like Karl Marx in their midst, and joined in celebrating the new prosperity. Employers typically were paternalistic and generally recognised the trade unions.[69] Companies provided their employees with welfare services ranging from housing, schools and churches, to libraries, baths, and gymnasia. Middle-class reformers did their best to assist the working classes' aspirations to middle-class norms of "respectability".

.jpg)

There was a spirit of libertarianism, says Porter, as people felt they were free. Taxes were very low, and government restrictions were minimal. There were still problem areas, such as occasional riots, especially those motivated by anti-Catholicism. Society was still ruled by the aristocracy and the gentry, who controlled high government offices, both houses of Parliament, the church, and the military. Becoming a rich businessman was not as prestigious as inheriting a title and owning a landed estate. Literature was doing well, but the fine arts languished as the Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased Britain's industrial prowess rather than its sculpture, painting or music. The educational system was mediocre; the main universities (outside Scotland) were likewise mediocre.[70] Historian Llewellyn Woodward has concluded:[71]

- For leisure or work, for getting or for spending, England was a better country in 1879 than in 1815. The scales were less weighted against the weak, against women and children, and against the poor. There was greater movement, and less of the fatalism of an earlier age. The public conscience was more instructed, and the content of liberty was being widened to include something more than freedom from political constraint ... Yet England in 1871 was by no means an earthly paradise. The housing and conditions of life of the working class in town & country were still a disgrace to an age of plenty.

In December 1844, Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers founded what is considered the first cooperative in the world. The founding members were a group of 28, around half of which were weavers, who decided to band together to open a store owned and managed democratically by the members, selling food items they could not otherwise afford. Ten years later, the British co-operative movement had grown to nearly 1,000 co-operatives. The movement also spread across the world, with the first cooperative financial institution founded in 1850 in Germany.

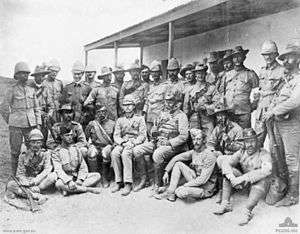

British Empire

The British Empire grew dramatically during the era.[72] The more advanced colonies of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa began their journey towards semi-independent dominion status. India eventually became independent, followed by all the other colonies that were established especially in Africa during the Era. In Australia, new provinces were founded with Victoria in 1835 and South Australia in 1842. The focus shifted from transportation of criminals to voluntary immigration. New Zealand became a British colony in 1839; in 1840 Maori chiefs seated sovereignty to Britain. In 1841 New Zealand became an autonomous colony. In Canada a constitutional crisis developed in 1837, involving the unification of largely British Upper Canada and largely French Lower Canada. Rebellions broke out. London sent Lord Durham to resolve the issue and his 1839 report opened the way for "responsible government" (that is, self-government). In South Africa the Dutch Boers made their "Great Trek to found Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State, defeating the Zulus in the process, 1835-1838; London annexed Natal in 1843 but recognized the independence of the Transvaal in 1852 in the Orange Free State in 1854. Nevertheless tensions escalated, especially with the discovery of gold. The result was the First Boer War in 1880-1881, and the intensely bitter Second Boer War, 1899–1902. The British finally prevailed, but lost prestige at home and abroad. In India, the East India Company lost its trade monopoly and became simply the government of those parts of India controlled directly by Britain. English was imposed as the medium of education. A major revolt broke out in 1857 and suppressed brutally. The East India Company was merged into a new government agency. In China Britain took the lead, along with other major powers, in obtaining special trading and legal rights in a limited number of treaty ports. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain in 1842. David Livingstone led famous expeditions in central Africa, positioning Britain for favorable expansion of its colonial system in the Scramble for Africa during the 1880s. There were numerous revolts in violent conflicts in the British Empire, but there were no wars with other nations, apart from the limited Crimean war of 1854 with Russia. The major new policies included in rapid succession, the complete abolition of slavery in the West Indies and African possessions, the end of transportation of convicts to Australia, loosening restrictions on colonial trade, and introducing responsible government.[73] [74]

Technology, science, and engineering

The Victorians were impressed by science and progress and felt that they could improve society in the same way as they were improving technology. Britain was the leading world centre for advanced engineering and technology. Its engineering firms were in worldwide demand for designing and constructing railways.[75][76]

A central development during the Victorian era was the improvement of communication. The new railways all allowed goods, raw materials, and people to be moved about, rapidly facilitating trade and industry. The financing of railways became an important specialty of London's financiers.[77] The railway system led to a reorganisation of society more generally, with "railway time" being the standard by which clocks were set throughout Britain; the complex railway system setting the standard for technological advances and efficiency. Steam ships such as the SS Great Britain and SS Great Western made international travel more common but also advanced trade, so that in Britain it was not just the luxury goods of earlier times that were imported into the country but essentials and raw materials such as corn and cotton from the United States and meat and wool from Australia. One more important innovation in communications was the Penny Black, the first postage stamp, which standardised postage to a flat price regardless of distance sent.

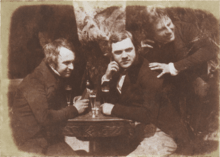

Even later communication methods such as electric power, telegraph, and telephones, had an impact. Photography was realised in 1839 by Louis Daguerre in France and William Fox Talbot in Britain. By 1889, hand-held cameras were available.[78]

Similar sanitation reforms, prompted by the Public Health Acts 1848 and 1869, were made in the crowded, dirty streets of the existing cities, and soap was the main product shown in the relatively new phenomenon of advertising. A great engineering feat in the Victorian Era was the sewage system in London. It was designed by Joseph Bazalgette in 1858. He proposed to build 82 mi (132 km) of sewer system linked with over 1,000 mi (1,600 km) of street sewers. Many problems were encountered but the sewers were completed. After this, Bazalgette designed the Thames Embankment which housed sewers, water pipes and the London Underground. During the same period, London's water supply network was expanded and improved, and a gas network for lighting and heating was introduced in the 1880s.[79]

The model town of Saltaire was founded, along with others, as a planned environment with good sanitation and many civic, educational and recreational facilities, although it lacked a pub, which was regarded as a focus of dissent. During the Victorian era, science grew into the discipline it is today. In addition to the increasing professionalism of university science, many Victorian gentlemen devoted their time to the study of natural history. This study of natural history was most powerfully advanced by Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution first published in his book On the Origin of Species in 1859.

_LACMA_M.2008.40.98.8.jpg)

Although initially developed in the early years of the 19th century, gas lighting became widespread during the Victorian era in industry, homes, public buildings and the streets. The invention of the incandescent gas mantle in the 1890s greatly improved light output and ensured its survival as late as the 1960s. Hundreds of gasworks were constructed in cities and towns across the country. In 1882, incandescent electric lights were introduced to London streets, although it took many years before they were installed everywhere.

Railways

One of the great achievements of the Industrial Revolution in Britain was the introduction and advancement of railway systems, not only in the United Kingdom and the British Empire but across the world. British engineers and financiers designed, built and funded many major systems. They retained an ownership share even while turning over management to locals; that ownership was largely liquidated in 1914–1916 to pay for the World War. Railroads originated in England because industrialists had already discovered the need for inexpensive transportation to haul coal for the new steam engines, to supply parts to specialized factories, and to take products to market. The existing system of canals was inexpensive but was too slow and too limited in geography.[80]

The engineers and businessmen needed to create and finance a railway system were available; they knew how to invent, to build, and to finance a large complex system. The first quarter of the 19th century involved numerous experiments with locomotives and rail technology. By 1825 railways were commercially feasible, as demonstrated by George Stephenson (1791–1848) when he built the Stockton and Darlington. On his first run, his locomotive pulled 38 freight and passenger cars at speeds as high as 12 miles per hour. Stephenson went on to design many more railways and is best known for standardizing designs, such as the "standard gauge" of rail spacing, at 4 feet 8½ inches.[81] Thomas Brassey (1805–70) was even more prominent, operating construction crews that at one point in the 1840s totalled 75,000 men throughout Europe, the British Empire, and Latin America.[82] Brassey took thousands of British engineers and mechanics across the globe to build new lines. They invented and improved thousands of mechanical devices, and developed the science of civil engineering to build roadways, tunnels and bridges.[83]

Britain had a superior financial system based in London that funded both the railways in Britain and also in many other parts of the world, including the United States, up until 1914. The boom years were 1836 and 1845–47 when Parliament authorised 8,000 miles of lines at a projected cost of £200 million, which was about the same value as the country's annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at that time. A new railway needed a charter, which typically cost over £200,000 (about $1 million) to obtain from Parliament, but opposition could effectively prevent its construction. The canal companies, unable or unwilling to upgrade their facilities to compete with railways, used political power to try to stop them. The railways responded by purchasing about a fourth of the canal system, in part to get the right of way, and in part to buy off critics. Once a charter was obtained, there was little government regulation, as laissez-faire and private ownership had become accepted practices.[84]

The different lines typically had exclusive territory, but given the compact size of Britain, this meant that multiple competing lines could provide service between major cities. George Hudson (1800–1871) became the "railway king" of Britain. He merged various independent lines and set up a "Clearing House" in 1842 which rationalized interconnections by establishing uniform paperwork and standard methods for transferring passengers and freight between lines, and rates when one system used freight cars owned by another. By 1850, rates had fallen to a penny a ton mile for coal, at speeds of up to fifty miles an hour. Britain now had had the model for the world in a well integrated, well-engineered system that allowed fast, cheap movement of freight and people, and which could be replicated in other major nations.

_The_Railway_Station_colorized.jpg)

The railways directly or indirectly employed tens of thousands of engineers, mechanics, repairmen and technicians, as well as statisticians and financial planners. They developed new and more efficient and less expensive techniques. Most important, they created a mindset of how technology could be used in many different forms of business. Railways had a major impact on industrialization. By lowering transportation costs, they reduced costs for all industries moving supplies and finished goods, and they increased demand for the production of all the inputs needed for the railroad system itself. By 1880, there were 13,500 locomotives which each carried 97,800 passengers a year, or 31,500 tons of freight.[85]

India provides an example of the London-based financiers pouring money and expertise into a very well built system designed for military reasons (after the Mutiny of 1857), and with the hope that it would stimulate industry. The system was overbuilt and much too elaborate and expensive for the small amount of freight traffic it carried. However, it did capture the imagination of the Indians, who saw their railways as the symbol of an industrial modernity—but one that was not realized until a century or so later.[86]

Health and medicine

Medicine progressed during Queen Victoria's reign. Although nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, had been proposed as an anaesthetic as far back as 1799 by Humphry Davy, it wasn't until 1846 when an American dentist named William Morton started using ether on his patients that anaesthetics became common in the medical profession.[87] In 1847 chloroform was introduced as an anaesthetic by James Young Simpson.[88] Chloroform was favoured by doctors and hospital staff because it is much less flammable than ether, but critics complained that it could cause the patient to have a heart attack.[88] Chloroform gained in popularity in England and Germany after John Snow gave Queen Victoria chloroform for the birth of her eighth child (Prince Leopold).[89] By 1920, chloroform was used in 80 to 95% of all narcoses performed in the UK and German-speaking countries.[88]

Anaesthetics made painless dentistry possible. At the same time sugar consumption in the British diet increased, greatly increasing instances of tooth decay .[90] As a result, more and more people were having teeth extracted and needing dentures. This gave rise to "Waterloo Teeth", which were real human teeth set into hand-carved pieces of ivory from hippopotamus or walrus jaws.[90][91] The teeth were obtained from executed criminals, victims of battlefields, from grave-robbers, and were even bought directly from the desperately impoverished.[90]

Medicine also benefited from the introduction of antiseptics by Joseph Lister in 1867 in the form of carbolic acid (phenol).[92] He instructed the hospital staff to wear gloves and wash their hands, instruments, and dressings with a phenol solution and in 1869, he invented a machine that would spray carbolic acid in the operating theatre during surgery.[92]

Population

The Victorian era was a time of unprecedented population growth in Britain. The population rose from 13.9 million in 1831 to 32.5 million in 1901. Two major contributary factors were fertility rates and mortality rates. Britain was the first country to undergo the demographic transition and the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions.

Britain had the lead in rapid economic and population growth. At the time, Thomas Malthus believed this lack of growth outside Britain was due to the 'Malthusian trap'. That is, the tendency of a population to expand geometrically while resources grew more slowly, reaching a crisis (such as famine, war, or epidemic) which would reduce the population to a sustainable size. Britain escaped the 'Malthusian trap' because the Industrial Revolution had a positive impact on living standards.[93] People had more money and could improve their standards; therefore, a population increase was sustainable.

Fertility rates

In the Victorian era, fertility rates increased in every decade until 1901, when the rates started evening out.[94] There were several reasons for this. One is biological: with improving living standards, a higher proportion of women were biologically able to have children. Another possible explanation is social. In the 19th century, the marriage rate increased, and people were getting married at a very young age until the end of the century, when the average age of marriage started to increase again slowly. The reasons why people got married younger and more frequently are uncertain. One theory is that greater prosperity allowed people to finance marriage and new households earlier than previously possible. With more births within marriage, it seems inevitable that marriage rates and birth rates would rise together.

Birth rates were originally measured by the 'crude birth rate' – births per year divided by total population. This is indeed a crude measure, as key groups and their fertility rates are not clear. It is likely to be affected mainly by changes in the age distribution of the population. The Net Reproduction Rate was then introduced as an alternative measure: it measures the average fertility rate of women of child-bearing ages.

High rates of birth also occurred because of a lack of birth control. Mainly because women lacked knowledge of birth control methods and the practice was seen as unrespectable.[95] The evening out of fertility rates at the beginning of the 20th century was mainly the result of a few big changes: availability of forms of birth control, and changes in people's attitude towards sex.[96]

Mortality rates

The mortality rates in England changed greatly through the 19th century. There was no catastrophic epidemic or famine in England or Scotland in the 19th century – it was the first century in which a major epidemic did not occur throughout the whole country, and deaths per 1000 of population per year in England and Wales fell from 21.9 from 1848 to 1854 to 17 in 1901 (cf, for instance, 5.4 in 1971).[97] Social class had a significant effect on mortality rates: the upper classes had a lower rate of premature death early in the 19th century than poorer classes did.[98]

Environmental and health standards rose throughout the Victorian era; improvements in nutrition may also have played a role, although the importance of this is debated.[97] Sewage works were improved, as was the quality of drinking water. With a healthier environment, diseases were caught less easily and did not spread as much. Technology improved because the population had more money to spend on medical technology (for example, techniques to prevent death in childbirth, so that more women and children survived), which also led to a greater number of cures for diseases. However, there was a cholera epidemic in London in 1848–49, which killed 14,137 people, and another in 1853 killing 10,738. Reformers rushed to complete a modern London sewerage system.[99] Tuberculosis (spread in congested dwellings), lung diseases from the mines and typhoid remained common.

High culture

Gothic Revival architecture became increasingly significant during the period, leading to the Battle of the Styles between Gothic and Classical ideals. Charles Barry's architecture for the new Palace of Westminster, which had been badly damaged in an 1834 fire, was built in the medieval style of Westminster Hall, the surviving part of the building. It constructed a narrative of cultural continuity, set in opposition to the violent disjunctions of Revolutionary France, a comparison common to the period, as expressed in Thomas Carlyle's The French Revolution: A History and Charles Dickens' Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities. Gothic was also supported by critic John Ruskin, who argued that it epitomised communal and inclusive social values, as opposed to Classicism, which he considered to epitomise mechanical standardisation.

The middle of the 19th century saw The Great Exhibition of 1851, the first World's Fair, which showcased the greatest innovations of the century. At its centre was the Crystal Palace, a modular glass and iron structure – the first of its kind. It was condemned by Ruskin as the very model of mechanical dehumanisation in design but later came to be presented as the prototype of Modern architecture. The emergence of photography, showcased at the Great Exhibition, resulted in significant changes in Victorian art with Queen Victoria being the first British monarch to be photographed. John Everett Millais was influenced by photography (notably in his portrait of Ruskin) as were other Pre-Raphaelite artists. It later became associated with the Impressionistic and Social Realist techniques that would dominate the later years of the period in the work of artists such as Walter Sickert and Frank Holl.

The long-term effect of the reform movements was to tightly link the nonconformist element with the Liberal party. The dissenters gave significant support to moralistic issues, such as temperance and sabbath enforcement. The nonconformist conscience, as it was called, was repeatedly called upon by Gladstone for support for his moralistic foreign policy.[100] In election after election, Protestant ministers rallied their congregations to the Liberal ticket. In Scotland, the Presbyterians played a similar role to the Nonconformist Methodists, Baptists and other groups in England and Wales.[101] The political strength of Dissent faded sharply after 1920 with the secularization of British society in the 20th century.

The middle class

The rise of the middle class during the era had a formative effect on its character; the historian Walter E. Houghton reflects that "once the middle class attained political as well as financial eminence, their social influence became decisive. The Victorian frame of mind is largely composed of their characteristic modes of thought and feeling".[102]

Industrialisation brought with it a rapidly growing middle class whose increase in numbers had a significant effect on the social strata itself: cultural norms, lifestyle, values and morality. Identifiable characteristics came to define the middle-class home and lifestyle. Previously, in town and city, residential space was adjacent to or incorporated into the work site, virtually occupying the same geographical space. The difference between private life and commerce was a fluid one distinguished by an informal demarcation of function. In the Victorian era, English family life increasingly became compartmentalised, the home a self-contained structure housing a nuclear family extended according to need and circumstance to include blood relations. The concept of "privacy" became a hallmark of the middle-class life.

The English home closed up and darkened over the decade (1850s), the cult of domesticity matched by a cult of privacy. Bourgeois existence was a world of interior space, heavily curtained off and wary of intrusion, and opened only by invitation for viewing on occasions such as parties or teas. "The essential, unknowability of each individual, and society's collaboration in the maintenance of a façade behind which lurked innumerable mysteries, were the themes which preoccupied many mid-century novelists."[103]

— Kate Summerscale quoting historian Anthony S. Wohl

Journalism

In 1817, Thomas Barnes became general editor of The Times; he was a political radical, a sharp critic of parliamentary hypocrisy and a champion of freedom of the press.[104] Under Barnes and his successor in 1841, John Thadeus Delane, the influence of The Times rose to great heights, especially in politics and in the financial district (the City of London). It spoke of reform.[105] The Times originated the practice of sending war correspondents to cover particular conflicts. W. H. Russell wrote immensely influential dispatches on the Crimean War of 1853–1856; for the first time, the public could read about the reality of warfare. Russell wrote one dispatch that highlighted the surgeons' "inhumane barbarity" and the lack of ambulance care for wounded troops. Shocked and outraged, the public reacted in a backlash that led to major reforms especially in the provision of nursing, led by Florence Nightingale.[106]

The Manchester Guardian was founded in Manchester in 1821 by a group of non-conformist businessmen. Its most famous editor, Charles Prestwich Scott, made the Guardian into a world-famous newspaper in the 1890s. The Daily Telegraph in 1856 became the first penny newspaper in London. It was funded by advertising revenue based on a large audience.

Leisure

Opportunities for leisure activities increased dramatically as real wages continued to grow and hours of work continued to decline. In urban areas the nine-hour workday became increasingly the norm; the Factory Act 1874 limited the working week to 56.5 hours, encouraging the movement towards an eventual eight-hour workday. Furthermore, a system of routine annual holidays came into play, starting with white-collar workers and moving into the working-class.[107][108] Some 200 seaside resorts emerged thanks to cheap hotels and inexpensive railway fares, widespread bank holidays and the fading of many religious prohibitions against secular activities on Sundays.[109]

By the late Victorian era the leisure industry had emerged in all cities. It provided scheduled entertainment of suitable length at convenient locales at inexpensive prices. These included sporting events, music halls, and popular theatre. By 1880 football was no longer the preserve of the social elite, as it attracted large working-class audiences. Average attendance was 5000 in 1905, rising to 23,000 in 1913. That amounted to 6 million paying customers with a weekly turnover of £400,000. Sports by 1900 generated some three percent of the total gross national product. Professional sports were the norm, although some new activities reached an upscale amateur audience, such as lawn tennis and golf. Women were now allowed in some sports, such as archery, tennis, badminton and gymnastics.[110]

Housing

The very rapid growth in population in the 19th century in the cities included the new industrial and manufacturing cities, as well as service centres such as Edinburgh and London. The critical factor was financing, which was handled by building societies that dealt directly with large contracting firms.[111][112] Private renting from housing landlords was the dominant tenure. P. Kemp says this was usually of advantage to tenants.[113] People moved in so rapidly that there was not enough capital to build adequate housing for everyone, so low income newcomers squeezed into increasingly overcrowded slums. Clean water, sanitation, and public health facilities were inadequate; the death rate was high, especially infant mortality, and tuberculosis among young adults. Cholera from polluted water and typhoid were endemic. Unlike rural areas, there were no famines such as the one which devastated Ireland in the 1840s.[114][115][116]

Poverty

19th-century Britain saw a huge population increase accompanied by rapid urbanisation stimulated by the Industrial Revolution. Wage rates improved steadily; real wages (after taking inflation into account) were 65 percent higher in 1901, compared to 1871. Much of the money was saved, as the number of depositors in savings banks rose from 430,000 in 1831, to 5.2 million in 1887, and their deposits from £14 million to over £90 million.[117] People flooded into industrial areas and commercial cities faster than housing could be built, resulting in overcrowding and lagging sanitation facilities such as fresh water and sewage.

These problems were magnified in London, where the population grew at record rates. Large houses were turned into flats and tenements, and as landlords failed to maintain these dwellings, slum housing developed. Kellow Chesney described the situation as follows: "Hideous slums, some of them acres wide, some no more than crannies of obscure misery, make up a substantial part of the metropolis... In big, once handsome houses, thirty or more people of all ages may inhabit a single room."[118] Significant changes happened in the British Poor Law system in England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. These included a large expansion in workhouses (or poorhouses in Scotland), although with changing populations during the era.

Child labour

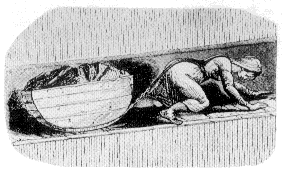

The early Victorian era before the reforms of the 1840s became notorious for the employment of young children in factories and mines and as chimney sweeps.[120][121] Child labour played an important role in the Industrial Revolution from its outset: novelist Charles Dickens, for example, worked at the age of 12 in a blacking factory, with his family in a debtors' prison. Reformers wanted the children in school: in 1840 only about 20 percent of the children in London had any schooling. By 1860 about half of the children between 5 and 15 were in school (including Sunday school).[122]

The children of the poor were expected to help towards the family budget, often working long hours in dangerous jobs for low wages.[118] Agile boys were employed by the chimney sweeps; small children were employed to scramble under machinery to retrieve cotton bobbins; and children were also employed to work in coal mines, crawling through tunnels too narrow and low for adults. Children also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or sold matches, flowers, and other cheap goods.[118] Some children undertook work as apprentices to respectable trades, such as building, or as domestic servants (there were over 120,000 domestic servants in London in the mid 19th century). Working hours were long: builders might work 64 hours a week in summer and 52 in winter, while domestic servants were theoretically on duty 80-hours a week.

Mother bides at home, she is troubled with bad breath, and is sair weak in her body from early labour. I am wrought with sister and brother, it is very sore work; cannot say how many rakes or journeys I make from pit's bottom to wall face and back, thinks about 30 or 25 on the average; the distance varies from 100 to 250 fathom. I carry about 1 cwt. and a quarter on my back; have to stoop much and creep through water, which is frequently up to the calves of my legs.

- — Isabella Read, 12 years old, coal-bearer, testimony gathered by Ashley's Mines Commission 1842[119]

As early as 1802 and 1819, Factory Acts were passed to limit the working hours of children in factories and cotton mills to 12 hours per day. These acts were largely ineffective and after radical agitation, by for example the "Short Time Committees" in 1831, a Royal Commission recommended in 1833 that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours per day, children aged 9–11 a maximum of eight hours, and children under the age of nine should no longer be permitted to work. This act, however, only applied to the textile industry, and further agitation led to another act in 1847 limiting both adults and children to 10-hour working days.[122]

Morality

Victorian morality was a surprising new reality. The changes in moral standards and actual behaviour across the British were profound. Historian Harold Perkin wrote:

Between 1780 and 1850 the English ceased to be one of the most aggressive, brutal, rowdy, outspoken, riotous, cruel and bloodthirsty nations in the world and became one of the most inhibited, polite, orderly, tender-minded, prudish and hypocritical.[123]

Historians continue to debate the various causes of this dramatic change. Asa Briggs emphasizes the strong reaction against the French Revolution, and the need to focus British efforts on its defeat and not be diverged by pleasurable sins. Briggs also stresses the powerful role of the evangelical movement among the Nonconformists, as well as the Evangelical faction inside the established Church of England. The religious and political reformers set up organizations that monitored behaviour, and pushed for government action.[124]

Among the higher social classes, there was a marked decline in gambling, horse races, and obscene theatres; there was much less heavy gambling or patronage of upscale houses of prostitution. The highly visible debauchery characteristic of aristocratic England in the early 19th century simply disappeared.[125]

Historians agree that the middle classes not only professed high personal moral standards, but actually followed them. There is a debate whether the working classes followed suit. Moralists in the late 19th century such as Henry Mayhew decried the slums for their supposed high levels of cohabitation without marriage and illegitimate births. However new research using computerized matching of data files shows that the rates of cohabitation were quite low—under 5%—for the working class and the poor. By contrast, in 21st-century Britain nearly half of all children are born outside marriage, and nine in ten newlyweds have been cohabitating.[126]

Crime, police and prisons

Crime was getting exponentially worse. There were 4,065 arrests for criminal offenses in 1805, tripling to 14,437 in 1835 and doubling to 31,309 in 1842 in England and Wales.[127]

18th-century British criminology had emphasized severe punishment. Slowly capital punishment was replaced by transportation, first to the American colonies and then to Australia,[128] and, especially, by long-term incarceration in newly built prisons. As one historian points out, "Public and violent punishment which attacked the body by branding, whipping, and hanging was giving way to reformation of the mind of the criminal by breaking his spirit, and encouraging him to reflect on his shame, before labour and religion transformed his character."[129] Crime rates went up, leading to calls for harsher measures ito stop the 'flood of criminals' released under the penal servitude system. The reaction from the committee set up under the commissioner of prisons, Colonel Edmund Frederick du Cane, was to increase minimum sentences for many offences with deterrent principles of 'hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed'.[130] As the prisons grew more numerous, they became more depraved. Historian S. G. Checkland says, "It was sunk in promiscuity and squalor, jailers' tyranny and greed, and administrative confusion."[131] In 1877 du Cane encouraged Disraeli's government to remove all prisons from local government; he held a firm grip on the prison system till his forced retirement in 1895. By the 1890s, the prison population was over 20,000.

By the Victorian era, penal transportation to Australia was falling out of use since it did not reduce crime rates.[132] The British penal system underwent a transition from harsh punishment to reform, education, and training for post-prison livelihoods. The reforms were controversial and contested. In 1877-1914 era a series of major legislative reforms enabled significant improvement in the penal system. In 1877, the previously localized prisons were nationalized in the Home Office under a Prison Commission. The Prison Act of 1898 enabled the Home Secretary to impose multiple reforms on his own initiative, without going through the politicized process of Parliament. The Probation of Offenders Act of 1907 introduced a new probation system that drastically cut down the prison population, while providing a mechanism for transition back to normal life. The Criminal Justice Administration Act of 1914 required courts to allow a reasonable time before imprisonment was ordered for people who did not pay their fines. Previously tens of thousands of prisoners had been sentenced solely for that reason. The Borstal system after 1908 was organized to reclaim young offenders, and the Children Act of 1908 prohibited imprisonment under age 14, and strictly limited that of ages 14 to 16. The principal reformer was Sir Evelyn Ruggles-Brise, the chair of the Prison Commission.[133][134]

Prostitution

During Victorian England, prostitution was seen as a "great social evil" by clergymen and major news organizations, but many feminists viewed prostitution as a means of economic independence for women. Estimates of the number of prostitutes in London in the 1850s vary widely, but in his landmark study, Prostitution, William Acton reported an estimation of 8,600 prostitutes in London alone in 1857.[135] The differing views on prostitution have made it difficult to understand its history.

Acclaimed feminist author Judith Walkowitz has multiple works focusing on the female point of view. Many sources blame economic disparities as leading factors in the rise of prostitution, and Walkowitz writes that the demographic within prostitution varied greatly. However, women who struggled financially were much more likely to be prostitutes than those with a secure source of income. Orphaned or half-orphaned women were more likely to turn to prostitution as a means of income.[136] While overcrowding in urban cities and the amount of job opportunities for females were limited, Walkowitz argues that there were other variables that lead women to prostitution. Walkowitz acknowledges that prostitution allowed for women to feel a sense of independence and self-respect[136]. Although many assume that pimps controlled and exploited these prostitutes, some women managed their own clientele and pricing. It's evident that women were exploited by this system, yet Walkowitz explains that prostitution was often their opportunity to gain social and economic independence[136]. Prostitution at this time was regarded by women in the profession to be a short-term position, and once they earned enough money, there were hopes that they would move on to a different profession.[137]

As previously stated, the arguments for and against prostitution varied greatly from it being perceived as a mortal sin or desperate decision to an independent choice. While there were plenty of people publicly denouncing prostitution in England, there were also others who took opposition to them. One event that sparked a lot of controversy was the implementation of the Contagious Diseases Acts. This was a series of three acts in 1864,1866, and 1869 that allowed police officers to stop women whom they believed to be prostitutes and force them to be examined[136]. If the suspected woman was found with a venereal disease, they placed the woman into a Lock Hospital. Arguments made against the acts claimed that the regulations were unconstitutional and that they only targeted women.[138] In 1869, a National Association in opposition of the acts was created. Because women were excluded from the first National Association, the Ladies National Association was formed. The leader of that organization was Josephine Butler.[136] Butler was an outspoken feminist during this time who fought for many social reforms. Her book Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade describes her oppositions to the C.D. acts.[139] Along with the publication of her book, she also went on tours condemning the C.D acts throughout the 1870s.[140] Other supporters of reforming the acts included Quakers, Methodists, and many doctors.[138] Due to this additional campaigning against the C.D. acts, a repeal was eventually posted 1869. This repeal included 124 signatures, one of which being Florence Nightingale, another medical and social reformer of this time.[140] Eventually the acts were fully repealed in 1886.[138]

The book Prostitution-Action by Dr. William Acton included detailed reports on his observations of prostitutes and the hospitals they would be placed in if they were found with a venereal disease[135]. Acton believed that prostitution was a poor institution but it is a result of the supply and demand for it. He wrote that men had sexual desires and they sought to relieve them, and for many, prostitution was the way to do it[135]. While he referred to prostitutes as wretched women, he did note how the acts unfairly criminalized women and ignored the men involved[137][135].

Events

- 1832

- Passage of the first Reform Act.[141]

The 1843 launch of the Great Britain, the revolutionary ship of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

The 1843 launch of the Great Britain, the revolutionary ship of Isambard Kingdom Brunel - 1837

- Ascension of Queen Victoria to the throne.[141]

- 1838

- Treaty of Balta Liman (Great Britain trade alliance with the Ottoman Empire).

- 1839

- First Opium War (1839–42) fought between Britain and China.

- 1840

- Queen Victoria marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield. He had been naturalised and granted the British style of Royal Highness beforehand. For the next 17 years, he was known as HRH Prince Albert.

- 1840

- New Zealand becomes a British colony, through the Treaty of Waitangi. No longer part of New South Wales

First Opium War: British ships approaching Canton in May 1841

First Opium War: British ships approaching Canton in May 1841 - 1842

- Treaty of Nanking. The Massacre of Elphinstone's Army by the Afghans in Afghanistan results in the death or incarceration of 16,500 soldiers and civilians.[142] The Mines Act of 1842 banned women/children from working in coal, iron, lead and tin mining.[141] The Illustrated London News was first published.[143]

- 1845

- The Irish famine begins. Within 5 years it would become the UK's worst human disaster, with starvation and emigration reducing the population of Ireland itself by over 50%. The famine permanently changed Ireland's and Scotland's demographics and became a rallying point for nationalist sentiment that pervaded British politics for much of the following century.

- 1846

- Repeal of the Corn Laws.[141]

- 1848

- Death of around 2,000 people a week in a cholera epidemic.

- 1850

- Restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales. (Scotland did not follow until 1878.)

- 1851

- The Great Exhibition (the first World's Fair) is held at the Crystal Palace,[141] with great success and international attention. The Victorian gold rush. In ten years the Australian population nearly tripled.[144]

The Great Exhibition in London. The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to industrialise.

The Great Exhibition in London. The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to industrialise. - 1854

- Crimean War: Britain, France and Turkey declare limited war on Russia. Russia loses.

- 1857

- The Indian Mutiny, a concentrated revolt in northern India against the rule of the privately owned British East India Company. Violent findings and massacre and sin British victory. The East India Company is replaced by the British government beginning the period of the British Raj.

- 1858

- The Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, responds to the Orsini plot against French Emperor Napoleon III, the bombs for which were purchased in Birmingham, by attempting to make such acts a felony; the resulting uproar forces him to resign.

- 1859

- Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species, which leads to various reactions.[141] Victoria and Albert's first grandchild, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, is born – he later became William II, German Emperor. John Stuart Mill publishes On Liberty, a defence of the famous harm principle.

- 1861

- Death of Prince Albert;[141] Queen Victoria refuses to go out in public for many years, and when she did she wore a widow's bonnet instead of the crown.

- 1865

- Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is published.

- 1866

- An angry crowd in London, protesting against John Russell's resignation as Prime Minister, is barred from Hyde Park by the police; they tear down iron railings and trample on flower beds. Disturbances like this convince Derby and Disraeli of the need for further parliamentary reform.

- 1867

- The Constitution Act, 1867 passes and British North America becomes Dominion of Canada.

The defence of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879

The defence of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 - 1875

- Britain purchased Egypt's shares in the Suez Canal[141] as the African nation was forced to raise money to pay off its debts.

- 1876

- Scottish-born inventor Alexander Graham Bell patents the telephone.

- 1878

- Treaty of Berlin. Cyprus becomes a Crown colony.

- 1879

- The Battle of Isandlwana is the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War.

- 1881

- The British suffer defeat at the Battle of Majuba Hill, leading to the signing of a peace treaty and later the Pretoria Convention, between the British and the reinstated South African Republic, ending the First Boer War. Sometimes claimed to mark the beginning of the decline of the British Empire.[145]

- 1882

- British troops begin the occupation of Egypt by taking the Suez Canal, to secure the vital trade route and passage to India, and the country becomes a protectorate.

- 1884

- The Fabian Society is founded in London by a group of middle-class intellectuals, including Quaker Edward R. Pease, Havelock Ellis and E. Nesbit, to promote socialism.[146] Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany dies.

- 1885

- Blackpool Electric Tramway Company starts the first electric tram service in the United Kingdom.

- 1886

- Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and the Liberal Party tries passing the First Irish Home Rule Bill, but the House of Commons rejects it.

Daimler Wagonette, Ireland, c. 1899

Daimler Wagonette, Ireland, c. 1899 - 1888

- The serial killer known as Jack the Ripper murders and mutilates five (and possibly more) prostitutes on the streets of London.

- 1889

- Emily Williamson founds the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

British and Australian officers in South Africa during the Second Boer War

British and Australian officers in South Africa during the Second Boer War - 1870–1891

- Under the Elementary Education Act 1870, basic State Education becomes free for every child under the age of 10.[147]

- 1898

- British and Egyptian troops led by Horatio Kitchener defeat the Mahdist forces at the battle of Omdurman, thus establishing British dominance in the Sudan. Winston Churchill takes part in the British cavalry charge at Omdurman.

- 1899

- The Second Boer War is fought between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics. The Boers finally surrendered and the British annexed the Boer republics.

- 1901

- The death of Victoria sees the end of this era. The ascension of her eldest son, Edward, begins the Edwardian era.

See also

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland covers politics and diplomacy

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- Historiography of the British Empire

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Victorian decorative arts

- Victorian fashion

- Victorian morality

- Victorian literature

- Neo-Victorian

- Social history of England

- Women in the Victorian era

- Victoriana

- Horror Victorianorum

- Victorian cemeteries

- Gilded Age, in the United States

- Belle Époque, in France

Citations

- John Wolffe (1997). Religion in Victorian Britain: Culture and empire. Volume V. Manchester University Press. pp. 129–30. ISBN 9780719051845. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Dixon, Nicholas (2010). "From Georgian to Victorian". History Review. 2010 (68): 34–38. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- The UK and future Archived 15 February 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive, Government of the United Kingdom

- "Ireland – Population Summary". Homepage.tinet.ie. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Exiles and Emigrants Archived 22 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. National Museum of Australia

- Plunkett, John; et al., eds. (2012). Victorian Literature: A Sourcebook. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 2.

- Hewitt, Martin (Spring 2006). "Why the Notion of Victorian Britain Does Make Sense". Victorian Studies. 48 (3): 395–438. doi:10.2979/VIC.2006.48.3.395. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 17

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 18-19

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 13 and p. 32

- M Sadleir, Trollope (London 1945) p. 25-30

- G M Trevelyan, History of England (London 1926) p. 650

- Swisher, ed., Victorian England, pp. 248–50.

- Kinealy, Christine (1994), This Great Calamity, Gill & Macmillan, p. xv

- Lusztig, Michael (July 1995). "Solving Peel's Puzzle: Repeal of the Corn Laws and Institutional Preservation". Comparative Politics. 27 (4): 393–408. doi:10.2307/422226. JSTOR 422226.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS,MUMBAI. pp. 60–61.

- Jill C. Bender, The 1857 Indian Uprising and the British Empire (2016), 205pp.

- Dijkink, Gertjan; Knippenberg, Hans (2001). The Territorial Factor: Political Geography in a Globalising World. Amsterdam University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-90-5629-188-4. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Asa Briggs, The Age of Improvement 1783–1867 (1957) pp 236–85.

- On the interactions of Evangelicalism and utilitarianism see Élie Halévy, A History of the English People in 1815 (1924) 585-95; also 3:213-15.

- G.M. Young, Victorian England: Portrait of an Age (1936, 2nd ed, 1953), pp 1–6.

- Briggs, The Age of Improvement 1783–1867 (1957) p 447.

- Young, Victorian England: Portrait of an Age pp 10–12.

- On the interactions of Evangelicalism and utilitarianism see Élie Halévy, A History of the English People in 1815 (1924) 585-95; see pp 213–15.

- Llewellyn Woodward, The Age of Reform, 1815–1870 (1962), pp 28, 78–90, 446, 456, 464–65.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian church (1966) 1:7–9, 47–48.

- Walter E. Houghton, The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830–1870 (1957) p 33.

- , John Ramsden (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics (2005), p. 474.

- D. W. Bebbington, The Nonconformist Conscience. Chapel and Politics, 1870–1914 (1982).

- Sally Mitchell, Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia (2011), p 547

- Michael R. Watts (2015). The Dissenters: The crisis and conscience of nonconformity. Clarendon Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780198229698.

- Timothy Larsen, "A Nonconformist Conscience? Free Churchmen in Parliament in Nineteenth‐Century England." Parliamentary History 24#1 (2005): 107–119.

- Richard Helmstadter, "The Nonconformist Conscience" in Peter Marsh, ed., The Conscience of the Victorian State (1979) pp 135–72.

- Glaser, John F. (1958). "English Nonconformity and the Decline of Liberalism". The American Historical Review. 63 (2): 352–363. doi:10.2307/1849549. JSTOR 1849549.

- G. I. T. Machin, "Resistance to Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1828." Historical Journal 22#1 (1979): 115–139.

- Davis, R. W. (1966). "The Strategy of "Dissent" in the Repeal Campaign, 1820-1828". The Journal of Modern History. 38 (4): 374–393. doi:10.1086/239951. JSTOR 1876681.

- Olive Anderson, "Gladstone's Abolition of Compulsory Church Rates: a Minor Political Myth and its Historiographical Career." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 25#2 (1974): 185–198.

- G. I. T. Machin, "Gladstone and Nonconformity in the 1860s: The Formation of an Alliance'." Historical Journal 17 (1974): 347–64.