Transamerica Pyramid

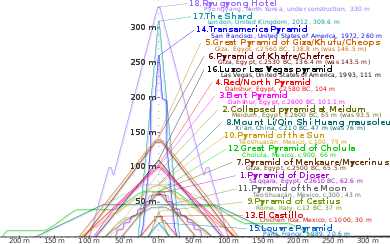

The Transamerica Pyramid at 600 Montgomery Street between Clay and Washington Streets in the Financial District of San Francisco, California, United States, is a 48-story futurist building and the second-tallest skyscraper in the San Francisco skyline. It was the tallest building in San Francisco from its inception in 1972 until 2018 when the newly constructed Salesforce Tower surpassed its height.[5] The building no longer houses the headquarters of the Transamerica Corporation, which moved its U.S. headquarters to Baltimore, Maryland. However, the building is still associated with the company by being depicted on the company's logo. Designed by architect William Pereira and built by Hathaway Dinwiddie Construction Company, the building stands at 853 feet (260 m). On completion in 1972 it was the eighth-tallest building in the world.[6] In February 2020 the building was sold to NYC investor Michael Shvo, although the sale has not yet closed.[7][8]

| Transamerica Pyramid | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

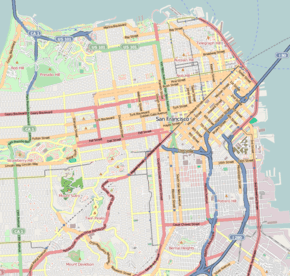

Transamerica Pyramid Location within San Francisco  Transamerica Pyramid Transamerica Pyramid (California)  Transamerica Pyramid Transamerica Pyramid (the United States) | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in San Francisco from 1969 to 2017[I] | |

| Preceded by | Bank of America Center |

| Surpassed by | Salesforce Tower (2017) |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Location | 600 Montgomery Street San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37.7952°N 122.4028°W |

| Construction started | December 1969 |

| Completed | 1972 |

| Cost | US$32 million |

| Owner | Transamerica Corporation |

| Management | Jones Lang LaSalle Americas, Inc. |

| Height | |

| Roof | 853 ft (260 m) |

| Top floor | 695 ft (212 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 48 |

| Floor area | 702,000 sq ft (65,200 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 18 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | William L. Pereira & Harry D. Som |

| Structural engineer | Chin & Hensolt, Inc. Glumac International Simonson & Simonson |

| Main contractor | Dinwiddie Construction Co. |

| Website | |

| pyramidcenter | |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

History

The Transamerica building was commissioned by Transamerica CEO John (Jack) R. Beckett, with the claim that he wished to allow light in the street below. Built on the site of the historic Montgomery Block, it has a structural height of 853 feet (260 m) and has 48 floors of retail and office space.

Construction began in 1969 and finished in 1972, and was overseen by San Francisco–based contractor Dinwiddie Construction, now Hathaway Dinwiddie Construction Company. Transamerica moved its headquarters to the new building from across the street, where it had been based in a flatiron-shaped building now occupied by the Church of Scientology of San Francisco.[9]

Although the tower is no longer Transamerica Corporation headquarters, it is still associated with the company and is depicted in the company's logo. The building is evocative of San Francisco and has become one of the many symbols of the city.[10] Designed by architect William Pereira, it faced opposition during planning and construction and was sometimes referred to by detractors as "Pereira's Prick".[11] John King of the San Francisco Chronicle summed up the improved opinion of the building in 2009 as "an architectural icon of the best sort – one that fits its location and gets better with age."[12] King also wrote in 2011 that it is "a uniquely memorable building, a triumph of the unexpected, unreal and engaging all at once. ... It is a presence and a persona, snapping into different focus with every fresh angle, every shift in light."[13]

The Transamerica Pyramid was the tallest skyscraper west of Chicago when constructed, surpassing the then Bank of America Center, also in San Francisco. It was surpassed by the Aon Center, Los Angeles, in 1974.

The building is thought to have been the intended target of a terrorist attack, involving the hijacking of airplanes as part of the Bojinka plot, which was foiled in 1995.[14]

In 1999, Transamerica was acquired by Dutch insurance company Aegon. When the non-insurance operations of Transamerica were later sold to GE Capital, Aegon retained ownership of the building as an investment.[10]

The Transamerica Pyramid was the tallest skyscraper in San Francisco from 1972 to 2017, when it was surpassed by the under-construction Salesforce Tower.[15]

Design

The land use and zoning restrictions for the parcel limited the number of square feet of office that could be built upon the lot, which sits at the north boundary of the financial district.

The building is a tall, four-sided pyramid with two "wings" to accommodate an elevator shaft on the east and a stairwell and a smoke tower on the west.[16] The top 212 feet (65 m) of the building is the spire.[17] There are four cameras pointed in the four cardinal directions at the top of this spire forming the "Transamerica Virtual Observation Deck." Four monitors in the lobby, whose direction and zoom can be controlled by visitors, display the cameras' views 24 hours a day. An observation deck on the 27th floor was closed: the Pyramid's official website says that it was closed to the public in 2001,[18] while the New York Times reported that it has been closed "[s]ince the late 1990s".[19] It was replaced by the virtual observation deck a few years later. The video signal from the "Transamericam" was used for years by a local TV news station for live views of traffic and weather in downtown San Francisco.

The top of the Transamerica Pyramid is covered with aluminum panels. During the Christmas holiday season, on Independence Day, and during the anniversary of 9/11, a brightly twinkling beacon called the "Crown Jewel" is lit at the top of the pyramid.[16]

Park

At the base of the building is a half-acre private park designed by Tom Galli called Redwood Park. A number of redwood trees were transplanted to this park from the Santa Cruz Mountains when the tower was built. It is generally open to the public during the daytime. It features a fountain and pond designed by Anthony Gazzardo complete with jumping frog sculpture, a Glenna Goodacre bronze sculpture of children at play, a bronze plaque honoring two dogs, and benches and tables offering respite to workers and visitors alike.[20]

Specifications

- The building's façade is covered in crushed quartz, giving the building its light color.[21]

- The four-story base contains 16,000 cubic yards (12,000 m3) of concrete and over 300 miles (480 km) of steel rebar.

- It has 3,678 windows.[13]

- The building's foundation is 9 feet (2.7 m) thick, the result of a 3-day, 24-hour continuous concrete pour. Several thousand dollars in coins were thrown into the pit by observers surrounding the site at street level during the pouring, for good luck.

- Only two of the building's 18 elevators reach the top floor.

- The original proposal was for a 1,150-foot (350 m) building, which for a year would have been the second-tallest completed building in the world. The proposal was rejected by the city planning commission, saying it would interfere with views of San Francisco Bay from Nob Hill.[6]

- The building is on the site that was the temporary home of A. P. Giannini's Bank of Italy after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed its office. Giannini founded Transamerica in 1928 as a holding company for his financial empire. Bank of Italy later became Bank of America.

- There is a plaque commemorating two famous dogs, Bummer and Lazarus, at the base of the building.[22]

- The hull of the whaling vessel Niantic, an artifact of the 1849 California Gold Rush, lay almost beneath the Transamerica Pyramid, and the location is marked by a historical plaque outside the building (California Historical Landmark #88).

- The aluminum cap is indirectly illuminated from within to balance the appearance at night.

- The two wings increase interior space at the upper levels. One extension is the top of elevator shafts while the other is a smoke evacuation tower for fire-fighting.[23]

- A glass pyramid cap sits at the top and encloses a red aircraft warning light and the brighter seasonal beacon.[24][25]

- Because of the shape of the building, the majority of the windows can pivot 360 degrees so they can be washed from the inside.[26]

- The spire is actually hollow[17] and lined with a 100-foot steel stairway at a 60 degree angle, followed by two steel ladders.

- The conference room (with 360 degree views of the city) is located on the 48th floor.

- Construction began in 1969 and the first tenants moved in during the summer of 1972.

Tenants

- Union Square Advisors LLC

- Greenhill & Co.[27]

- ATEL Capital Group

- Bank of America Merrill Lynch[28]

- Mars & Co[29]

- Incapture Group[30]

- TSG Consumer Partners

- Rembrandt Venture Partners

- URS Corporation

- Maynard, Cooper & Gale

- Pantheon Ventures

- Heller Manus Architects

- Crux Informatics

- On Lok

Similar structures

- The Shard, a building in London

- Burj Khalifa, a building in Dubai

- Ryugyong Hotel, a building in Pyongyang

See also

- List of tallest buildings in San Francisco

- 49-Mile Scenic Drive

- List of tallest buildings in the world

- List of tallest pyramids

References

- "Transamerica Pyramid". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- Transamerica Pyramid at Emporis

- "Transamerica Pyramid". SkyscraperPage.

- Transamerica Pyramid at Structurae

- "San Francisco's Salesforce Tower becomes tallest building on West Coast". ABC 7 News. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- "Official World's 200 Tallest High-rise Buildings". Emporis. January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- https://www.businessinsider.com/san-franciscos-iconic-transamerica-pyramid-sold-711-million-2020-2

- Li, Roland; Dineen, J.K. (21 April 2020). "Salesforce buys building next to SF headquarters for $145 million as offices remain shut". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- A Landmark Church at the Golden Gates. scientology.org

- Carolyn Said (May 29, 2004). "Transamerica Pyramid From corporate emblem to city landmark". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- Sorkin, Michael (1991). Exquisite Corpse: Writing on Buildings. New York; London: Vers0. ISBN 0-86091-323-6. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- King, John (December 27, 2009). "Pyramid's steep path from civic eyesore to icon". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- King, John (2011) Cityscapes: San Francisco and Its Buildings Berkeley, California: Heyday. p.2 ISBN 978-1-59714-154-3

- Irving, Reed Irvine; Kinkaid, Cliff (March 28, 2002). "Bojinka Back In The News". Media Monitor. Accuracy in Media. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- "Salesforce remakes San Francisco skyline with tallest West Coast office tower". The Mercury News. 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2017-07-29.

- "Transamerica Pyramid Center: Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: California. EYEWITNESS TRAVEL GUIDES. DK Publishing. 2014. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-4654-3266-7. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- HISTORY - Transamerica Pyramid Center. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- Pellissier, Hank (Sept. 4, 2010). "Pyramid Redwood Park". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- "Redwood Park | Transamerica Pyramid Center". pyramidcenter.com. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- Foster, L. (2011). The Photographer's Guide to San Francisco: Where to Find Perfect Shots and How to Take Them. The Photographer's Guide. Countryman Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58157-831-7. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Rubin, S. (2010). San Francisco Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Curiosities Series. Globe Pequot Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7627-6577-5. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Huell Howser. "Pyramid". California's Gold. Episode #3004. PBS. Archived from the original on 2010-10-20. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- Baker, Katie (October 19, 2010). "Ask the Appeal: When Does the TransAmerica Beacon Shine?". SF Appeal: San Francisco's Online Newspaper. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Dalton, Andrew (June 11, 2014). "San Francisco's Best Skyscrapers (And One Fogscraper)". SFist. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Douglas, G.H. (2004). Skyscrapers: A Social History of the Very Tall Building in America. McFarland. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-7864-2030-8. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- BofA renews lease at Transamerica Pyramid

- Mars & Co Group Contact Us

- Incapture Group Moves Into The Iconic Pyramid Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transamerica Pyramid. |

- Official website

- About the Pyramid at Transamerica Corporation

- Transamerica Pyramid at PropertyShark