Third Treaty of San Ildefonso

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso was a secret agreement signed on 1 October 1800 between the Spanish Empire and the French Republic by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange its North American colony of Louisiana for territories in Tuscany. The terms were later confirmed by the March 1801 Treaty of Aranjuez.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

North America; Louisiana-New Spain in white | |

| Context | Spain agrees to exchange Louisiana with France for territories in Italy |

| Signed | 1 October 1800[1] |

| Location | Real Sitio de San Ildefonso |

| Negotiators | |

| Parties | |

Background

For much of the 18th century, France and Spain were allies, but after the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, Spain joined the War of the First Coalition against the French Republic but was defeated in the War of the Pyrenees. In August 1795, Spain and France agreed to the Peace of Basel, with Spain ceding its half of the island of Hispaniola, the modern Dominican Republic.[2]

In the 1797 Second Treaty of San Ildefonso, Spain allied with France in the War of the Second Coalition and declared war on Britain. This resulted in the loss of Trinidad and, more seriously, Menorca, which Britain occupied from 1708–1782 and whose recovery was the major achievement of Spain's participation in the 1778–1783 Anglo-French War. Its loss damaged the prestige of the Spanish government, while the British naval blockade severely impacted the economy, which was highly dependent on trade with its South American colonies, particularly the import of silver from Mexico.[3]

The effect was to place the Spanish government under severe political and financial pressure, the national debt increasing eightfold between 1793 and 1798.[4] Louisiana was only part of Spain's immense empire in the Americas, which it received as a result of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[lower-alpha 1] Preventing encroachment by American settlers into the Mississippi Basin was costly and risked conflict with the US, whose merchant ships Spain relied on to evade the British blockade.[5]

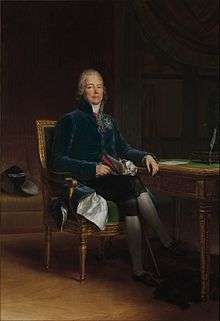

Colonies were viewed as valuable assets; the loss of the sugar islands of Saint-Domingue, Martinique, and Guadeloupe between 1791–1794 had a huge impact on French business.[lower-alpha 2] Restoring them was a priority and when Napoleon seized power in the November 1799 Coup of 18 Brumaire, he and his deputy Charles Talleyrand emphasised French expansion overseas.

Their strategy had a number of parts, one being the 1798–1801 Egyptian campaign, intended in part to strengthen French trading interests in the region. In South America, Talleyrand sought to move the border between French Guiana and Portuguese Brazil south to the Araguari or Amapá River, taking in large parts of Northern Brazil.[lower-alpha 3][6] A third was the restoration of New France in North America, lost after the 1756–1763 Seven Years' War, with Louisiana providing raw materials for French plantations in the Caribbean.[7]

The combination of French ambition and Spanish weakness made the return of Louisiana attractive to both, especially as Spain was being drawn into disputes with the US over navigation rights on the Mississippi River.[7] Talleyrand claimed French possession of Louisiana would allow them to protect Spanish South America from both Britain and the US.[lower-alpha 4]

Provisions

.jpg)

The Treaty was negotiated by French general Louis-Alexandre Berthier and the Spanish former Chief Minister Mariano Luis de Urquijo. In addition to Louisiana, Berthier was instructed to demand the Spanish colonies of East Florida and West Florida, plus ten Spanish warships.[8]

Urquijo rejected the request for the Floridas but agreed to Louisiana plus "...six ships of war in good condition built for seventy-four guns, armed and equipped and ready to receive French crews and supplies." In return, Charles IV wanted compensation for his son-in-law Louis, Infanta Duke of Parma, since France wanted to annex his inheritance of the Duchy of Parma.[9]

Details were vague, Clause II of the Treaty simply stating "it may consist of Tuscany...or the three Roman legations or of any other continental provinces of Italy which form a rounded state." Urquijo insisted Spain would hand over Louisiana and the ships only once France confirmed which Italian territories it would receive in return. Finally, the terms reaffirmed the alliance between France and Spain agreed upon in the 1796 Second Treaty of San Ildefonso.[10]

Aftermath

On 9 February 1801, France and the Austrian Emperor Francis II signed the Treaty of Lunéville, clearing the way for the Treaty of Aranjuez in March 1801. This confirmed the preliminary terms agreed at Idelfonso and created the short-lived Kingdom of Etruria for Maria Luisa's son-in-law Louis.[11]

.jpg)

The Treaty has traditionally been seen as extremely one-sided in favour of France, but modern historians are less critical. In reality, Spain exercised effective control only over a small part of the territory included in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase while an attempt to control US expansion into Spanish territories by the 1795 Pinckney's Treaty proved ineffective.[12] Spain's Chief Minister Manuel Godoy saw disposal as a necessity, later justifying it at length in his Memoirs.[lower-alpha 5][13]

From 1798–1800, France and the US waged an undeclared war at sea, the so-called Quasi-War, which was ended by the Convention of 1800 or Treaty of Mortefontaine. The US viewed French ambitions in North America with great concern, since with British Canada to the north, they wanted to avoid an aggressive and powerful France replacing Spain in the south.[14] For commercial reasons, Napoleon wanted to re-establish France in North America, the November 1801 Saint-Domingue expedition being the first step.[15] The March 1802 Treaty of Amiens ended the War of the Second Coalition and in October, Spain transferred Louisiana to France.[16]

However, by now it was clear the Saint-Domingue expedition was a catastrophic failure; between May 1802 and January 1803, a yellow fever epidemic killed over 40,000, including Napoleon's brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc.[17] This made Louisiana irrelevant and with France and Britain once more on the verge of hostilities, France sold Louisiana to the US for $15 million in April 1803, much of the purchase price being borrowed from British (Barings Bank) and Dutch bankers (Hope & Co.).[18]

See also

Footnotes

- Their ally France ceded it as compensation for Spanish concessions to Britain elsewhere.

- Losses were not confined to plantation owners in the Caribbean but inlaced slave traders in colonies like Senegal that supplied labour. France abolished slavery in 1794 but reimposed it in 1802 in French sugar-cane islands.

- Terms were contained in the draft 1797 Treaty of Paris which was never approved although similar conditions were imposed on Portugal in the 1801 Treaty of Madrid

- Letter to Urquijo; ...the power of America is bounded by the limit which it may suit the interests and the tranquillity of France and Spain to assign here. The French Republic... will be the wall of brass forever impenetrable to the combined efforts of England and America.

- Godoy wrote ...(Louisiana) not yielding much to our treasury, nor to our trade, and generating sizeable expenses in money and soldiers, ...the return...can be deemed as a gain, instead of a sacrifice...(Tuscany), cultivation perfect, industry flourishing, trade expanded...a million and a half inhabitants; state revenues of about three million pesos fuertes... The weakness of this argument is France was effectively returning territory to those it had taken it from in the first place.

References

- "Treaty of San Ildefonso : October 1, 1800". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School.

- "Dominican Republic; Elections and Events 1791-1849". The Library, UC San Diego. Regents of the University of California. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Sánchez, Rafael Torres (2015). Constructing a Fiscal Military State in Eighteenth Century Spain. AIAA. pp. 66 passim. ISBN 1137478659.

- Canga Argüelles, José (1826). Diccionario de hacienda (in Spanish). Impr. española de M. Calero. pp. 236–237.

- Maltby, William (2008). The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Empire. Palgrave. p. 168. ISBN 1403917922.

- Hecht, Susanna (2013). The Scramble for the Amazon and the Lost Paradise of Euclides da Cunha. University of Chicago. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0226322815.

- Kemp, Roger, ed. (2010). Documents of American Democracy. McFarland & Co. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0786442107.

- Rodriguez (ed), Junius P (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC Clio. p. 9. ISBN 0471191213.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Tarver, Micheal Hn (Author, Editor), Slape, Emily (Author, Editor) (2016). The Spanish Empire; An Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 161069421X.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Preliminary and Secret Treaty between the French Republic and His Catholic Majesty the King of Spain, Concerning the Aggrandizement of His Royal Highness the Infant Duke of Parma in Italy and the Retrocession of Louisiana". Yale Law School; Avalon Project Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Charles Esdaile (14 June 2003). The Peninsular War: A New History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4039-6231-7. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Maltby, William (2008). The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Empire. Palgrave. p. 168. ISBN 1403917922.

- Godoy, Manuel (1836). Memoirs Of Don Manuel De Godoy: Prince Of The Peace, Duke Del Alcudia, Count D'everamonte Volume 2 (2012 ed.). Nabu. pp. 47–59. ISBN 1279296461.

- Kemp, Roger (ed) (2010). Documents of American Democracy. McFarland & Co. pp. 160. ISBN 0786442107.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kemp, Roger (ed) (2010). Documents of American Democracy. McFarland & Co. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0786442107.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Real cédula expedida en Barcelona, a 15 de octubre de 1802, para que se entregue a la Francia la colonia y provincia de la Luisiana. Coleccion histórica completa de los tratdos, convenciones, capitulaciones, armistricios, y otros actos diplomáticos de todos los estados: de la America Latina comprendidos entre el golfo de Méjico y el cabo de Hornos, desde el año de 1493 hasta nuestros dias, Volume 4 (in Spanish). Paris. 1862. pp. 326–328.

- Kohn, George (ed), Scully, Mary-Louise (author) (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. Facts on File. p. 155. ISBN 978-0816069354. Retrieved 10 October 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Docevski, Bojan. "The Louisiana Purchase: Napoleon, eager for money to wage war on Britain, sold the land to U.S.–and a British bank financed the sale". The Vintage News. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

Sources

- Canga-Argüelles, José: Diccionario de Hacienda; (1826 (in Spanish));

- Godoy, Manuel; Memoirs Of Don Manuel De Godoy: Prince Of The Peace, Duke Del Alcudia, Count D'Everamonte Volume 2; (Nabu, 2012 ed.)

- Hecht, Susanna; The Scramble for the Amazon and the Lost Paradise of Euclides Da Cunha; (University of Chicago, 2003);

- Kemp, Roger (ed); Documents of American Democracy; (McFarland & Co, 2010);.

- Maltby, William; The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Empire; (Palgrave, 2008);

- Rodriguez,Junius P (ed); The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia; (ABC CLIO, 2002).

- Sánchez, Rafael Torres; Constructing a Fiscal Military State in Eighteenth Century Spain; (AIAA, 2015);

- Tarver, Micheal H (Author, Editor), Slape, Emily (Author, Editor); The Spanish Empire; An Historical Encyclopedia; (ABC-CLIO, 2016);

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. |