Convention of 1800

The Convention of 1800 or the Treaty of Mortefontaine[lower-alpha 1] between the United States of America and France ended the 1798–1800 Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war waged primarily in the Caribbean, and terminated the 1778 Treaty of Alliance.

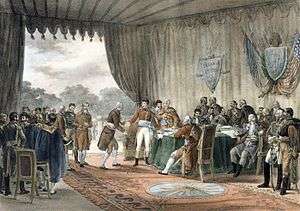

The signing of the Convention at Mortefontaine, September 30, 1800 | |

| Context | US and France end the 1798–1800 Quasi-War and terminate the 1778 Treaty of Alliance |

|---|---|

| Signed | 30 September 1800 |

| Location | Mortefontaine, France |

| Effective | 21 December 1801 |

| Signatories |

|

| Parties | |

Background

The 1778 Treaty of Alliance between France and the United States agreed that in return for French support in the American Revolutionary War, the US would defend French possessions in the Caribbean against foreign aggression. That meant the US was obliged to support France against their opponents in the 1792–1797 War of the First Coalition, which included Britain and the Netherlands, maritime powers with bases in the Caribbean.

There was little support in Congress for this since neutrality allowed Northern shipowners to earn huge profits evading the British blockade, and Southern plantation-owners feared the example set by France's abolition of slavery in 1794. Arguing that the 1793 execution of Louis XVI made existing agreements void, the 1794 Neutrality Act cancelled the military obligations of the 1778 treaty. France accepted that but on the basis of "benevolent neutrality:" French privateers would be given access to US ports, and captured British ships could be sold in American prize courts but not vice versa.[1] It soon became apparent that the US interpreted "neutrality" differently, and the commercial provisions of the 1795 Jay Treaty with Britain directly contradicted the 1778 Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France.

When the US delayed repayment of debts owed to France for loans made during the Revolutionary War, France began seizing American ships trading with the British West Indies in retaliation. That action and anger over the 1797 diplomatic dispute known as the XYZ Affair, resulted in Congress canceling the 1778 Treaties and authorising attacks on French warships in American waters on July 7, 1798, which led to the Quasi-War of 1798–1800. Adams rebuilt the Navy and it gained the upper hand, with limited support from the British Royal Navy.[lower-alpha 2]

President John Adams continued to seek a diplomatic solution to end the expensive war. Adams was increasingly concerned by French ambitions in North America. Efforts to manage it through diplomacy, including Pinckney's Treaty of 1795, did little to stop American settlers pushing into Spanish Louisiana; by 1800, nearly 400,000 or 7.3% of Americans lived in trans-Appalachian territories, including the new states of Kentucky and Tennessee.[2]

Western economic development required access to the Mississippi and the US much preferred a weak Spain to an aggressive and powerful France on their western and southern borders.[3] The discovery that French agents based in the US had conducted military surveys to determine how best to defend Louisiana led to the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts.[4]

Adams sent a commission in early 1799 to negotiate with France and to terminate the 1778 Alliance formally, confirm American neutrality, agree on compensation for shipping losses and end the Quasi-War. France wanted peace because Napoleon wanted to re-establish a North American Empire. He planned to use Louisiana as a supply base for French sugar-producing islands in the Caribbean.[5]

Provisions

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

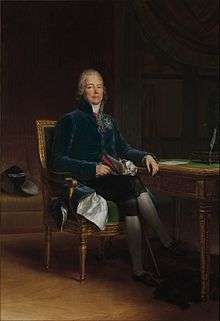

The commission of William Vans Murray, Oliver Ellsworth, and William Richardson Davie was approved in early 1799, but disputes between Federalists and Jeffersonians delayed their arrival in Paris until March 1800.[6] Even then, formal discussions did not begin until April and proceeded slowly; Napoleon's deputy and Foreign Minister Talleyrand was in no hurry because the Convention was just one part in a complex network of negotiations, including the transfer of Louisiana from Spain.

The main problem was the US demand of $20 million in compensation for shipping losses, which the French argued applied only if the 1778 Treaties remained in force. Since the US had abrogated both, their position was either the US confirmed the existing treaties and received compensation or insisted on new ones and received none.

By July 1800, France's strategic position was much stronger than when the Commission was first authorised in mid-1799. Napoleon was in firm control of government while Russia, with informal French support, had established the League of Armed Neutrality for active resistance to the British policy of searching neutral ships for contraband. Napoleon's victory over Austria at Marengo in June turned the War of the Second Coalition decisively in favour of France. Another victory at Hohenlinden in December forced Austria to make peace in the February 1801 Treaty of Lunéville.

With the commission aware of the increasing urgency of making a deal, Clause II of the Convention compromised by 'postponing discussions' on compensation but suspending the Treaties of 1778 and 1788 until this was resolved, and the US agreed to compensate its own citizens for the claimed damages of $20 million, although it was not until 1915 that the heirs received $3.9 million in settlement.[7] In return, Talleyrand reversed previous policy by confirming the principle of "free trade, free goods, freedom of convoy;" while connected to French backing for the League of Armed Neutrality, it was an unexpected bonus for the Commission.[8] The Convention was dated September 30, 1800 but arguments in Congress over the inclusion of Clause II meant that it was not fully ratified until December 21, 1801.[9]

Aftermath

%2C_plate_V_-_BL.jpg)

At the time, the Convention was generally viewed unfavourably in the US, especially the issue of compensation, which was not finally settled until 1915.[10] It also did little to address concerns over French objectives in North America; Charles Pinckney, US Ambassador to Spain,[lower-alpha 3] was instructed to acquire Louisiana and the Floridas from Spain but without success. However, modern historians argue that by ending the dispute with France, it facilitated the Louisiana Purchase while the US was not yet powerful enough to enforce its commercial independence.[11]

Negotiations between France and Britain to end the War of the Second Coalition began in late 1801, resulting in the March 1802 Treaty of Amiens, which brought temporary peace to Europe. In December 1801, a French expeditionary force landed on Saint-Domingue; shortly afterwards, the Americans finally obtained details of the 1801 Treaty of Aranjuez in which Spain agreed to transfer Louisiana to France.[12]

French ambitions were clear and the presence of 20,000–30,000 veteran troops in Saint-Domingue gave them the ability to implement that policy.[lower-alpha 4] However, by October 1802, it was clear the expedition had been a catastrophic failure. Napoleon's brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc died of yellow fever along with many of his men.[lower-alpha 5] Without the sugar islands, Louisiana was irrelevant, and France and Britain were once again on the verge of hostilities. In the Louisiana Purchase of April 1803, the US obtained the territory for $15 million, including 18 million francs or $3,750,000 as compensation for US shipping losses in 1796–1800. The Convention reflected the American policy against foreign entanglements and alliances.

Footnotes

- The United States refused to use the word "Treaty".

- Political sensitivities on both sides meant that it was small-scale and informal, but it included the sale of naval stores and munitions to the US, a shared signal system, and permission for merchantmen to join each other's convoys for safety.

- Not to be confused with his cousin, CC Pinckney, Ambassador to France during the XYZ Affair.

- In 1802, apart from militia the US had no standing army, and the Navy consisted of 5,400 sailors and marines.

- An estimated 15,000–22,000 out of 30,000, many of whom experienced veterans.

References

- Hyneman, Charles (April 1930). "Neutrality during the European Wars of 1792–1815: America's Understanding Of Her Obligations". The American Journal of International Law. 24 (2): 279–283. doi:10.2307/2189404. JSTOR 2189404.

- Irwin, Douglas, Sylla, Richard (2010). Founding Choices: American Economic Policy in the 1790s (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 287. ISBN 0-226-38475-6.

- Kemp, Roger (ed) (2010). Documents of American Democracy. McFarland & Co. p. 160. ISBN 0786442107.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Smith, James Morton (1956). Freedom's Fetters: Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (1966 ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0801490332.

- Junius P. Rodriguez (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 23–24.

- Lyon, E Wilson (September 1940). "The Franco-American Convention of 1800". The Journal of Modern History. XII: 309–310. doi:10.1086/236487. JSTOR 1874761.

- Rodriquez, Junius (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 236. ISBN 0471191213.

- Lyon, E Wilson (September 1940). "The Franco-American Convention of 1800". The Journal of Modern History. XII: 309–310. doi:10.1086/236487. JSTOR 1874761.

- Rohrs, Richard (September 1988). "The Federalist Party and the Convention of 1800". Diplomatic History. 12 (3): 237–260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1988.tb00475.x. JSTOR 24911802.

- Cox, Henry Bartholomew (1970). "A Nineteenth-Century Archival Search: The History of the French Spoliation Claims Papers". National Historical Publications Commission. doi:10.17723/aarc.33.4.j1p8086n15k65716.

- Hastedt, Glenn (2004). Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. Facts on File. p. 173. ISBN 0816046425.

- King, Rufus. "Madison Papers; To James Madison from Rufus King, 29 March 1801". Founders Archives. Original source: The Papers of James Madison, Secretary of State Series, vol. 1, 4 March–31 July 1801. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

Sources

- DeConde, Alexander; The Quasi-War: The Politics and Diplomacy of the Undeclared War with France, 1797–1801 (1966);

- Hastedt, Glenn; Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy; (Facts on File, 2004);

- Hyneman, Charles; "Neutrality during the European Wars of 1792–1815: America's Understanding Of Her Obligations" The American Journal of International Law, (1930); online

- Lyon, E. Wilson. "The Franco-American Convention of 1800." Journal of Modern History 12.3 (1940): 305-333 online

- Hill, Peter P. William Vans Murray, Federalist diplomat: the shaping of peace with France, 1797–1801 (1971)

- Rodriquez, Junius. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia; (ABC-CLIO, 2002);

- Rohrs, Richard C. "The Federalist Party and the Convention of 1800" Diplomatic History 12.3 (1988): 237-260. online

- Smith, James Morton; Freedom's Fetters: Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties; (Cornell University Press, 1966);

- Varg, Paul A; Foreign policies of the founding fathers (1963) pp 117–44 online free

Primary sources

- Causten, James H; A Sketch of the Claims of Sundry American Citizens: On the Government of the United States for Indemnity; For Depredations Committed on Their Property by the French Prior to the 30th September, 1800; Which Were Acknowledged by France and Voluntarily Surrendered to Her by the United States; (First published 1836, Forgotten Books, 2017);

- Cox, Henry Bartholomew; A Nineteenth-Century Archival Search: The History of the French Spoliation Claims Papers; (National Historical Publications Commission, 1970);

- Kemp, Roger (ed); Documents of American Democracy; (McFarland & Co, 2010);