Battle of Rocroi

The Battle of Rocroi on 19 May 1643 resulted in the victory of a French army under the Duc d'Enghien against Spanish forces under General Francisco de Melo only five days after the accession of Louis XIV to the throne of France late in the Thirty Years' War. The battle is considered by many as the downfall of the perceived invincibility of the Tercio, the Spanish army unit that dominated European battlefields in the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century. [5] In fact, after Rocroi, the Spanish abandoned the tercio system and began to use linear Dutch-style battalions like the French.[5]

| Battle of Rocroi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659) | |||||||

Rocroi, el último tercio, by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau (2011) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Duc d'Enghien |

Francisco de Melo Paul-Bernard de Fontaines † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000[1] 15,000 infantry 7,000 cavalry 14 guns |

23,050[2] 18,000 infantry (7,000 Spanish) 5,050 cavalry 18 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,000 dead or wounded [3] |

10,000[4] 6,000 killed or wounded 4,000 captured 18 guns | ||||||

Context

From 1618 on, the Thirty Years' War had been raging in Germany between the Spanish Habsburgs under Philip IV of Spain and Protestant powers. Fearing strengthened Habsburg presence at its borders, France had in 1635 declared war in support of the Protestant Anti-Habsburg States, despite being a Catholic power and having suppressed the Huguenot rebellions at home. An initial invasion of the Spanish Netherlands had ended in failure, with the French retreating to their borders for the next several years.

On 4 December 1642 the French royal adviser Cardinal Richelieu died, and Louis XIII fell ill in the early spring of 1643. After the king died on 14 May 1643, his son Louis XIV inherited the Kingdom of France. Despite receiving overtures of peace, the new king did not wish to change the course of the war, and French military pressure on Franche-Comté, Catalonia, and Spanish Flanders remained persistent.

As it had done the year before at the Battle of Honnecourt, the renowned Spanish Army of Flanders advanced through the Ardennes and into northern France with 23,050 men, intending to relieve the French pressure on other fronts.[2] The Duc d'Enghien, commander of a French army in Amiens, was appointed to stop the Spanish incursion. Although just 21 years old, he was experienced and equipped with worthy subordinates, among them Marshal Jean de Gassion. The total French forces in the area numbered around 22,000.[1]

Prelude

The Spanish troops under Francisco de Melo advanced towards and besieged Rocroi, a fortress town garrisoned by a few hundred French. A vital logistics hub, Rocroi commanded the route to the valley of the Oise. D'Enghien followed de Melo's numerically superior army closely. On 17 May d'Enghien learned of the death of King Louis, but kept the news secret from his army[6].

Word then reached d'Enghien of 6,000 Spanish reinforcements on their way to Rocroi. Reacting quickly, the duke prepared his army to give battle before the Spanish reinforcements arrived.

Learning of the French advance, de Melo decided to engage the oncoming forces rather than invest in the siege of Rocroi, as his army was stronger than the opposition [7]. Besides, the Spanish viewed the battle as an opportunity to win a decisive victory in Northern France. De Melo left a detachment of his army at Rocroi to prevent action from the garrison and moved his army to battle.

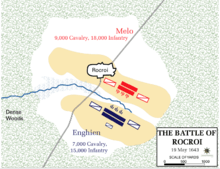

Enghien advanced along the Oise road and assembled his force along a ridge looking down on the besieged town of Rocroi. The Spanish quickly formed up between the town and the ridge. The French army was arranged with two lines of infantry in the center, squadrons of cavalry on each wing, and with a thin line of artillery at the front. The Spanish army was similarly arranged, but with its infantry deployed in their traditional tercio pike squares. The two armies exchanged some fire on the afternoon of 18 May, but the full battle did not occur until the following day.

Battle

The battle began after dawn broke, with the French infantry launching a failed attack on the Spanish tercios. The cavalry on the French left advanced against d'Enghien's orders, and were also forced to retreat. The Spanish cavalry launched a successful counter-attack and nearly routed the French cavalry, but the French reserve moved in and succeeded in checking the Spanish. At this point in the fighting the French left and center were in distress.

Meanwhile, on the French right, cavalry under the command of Jean de Gassion routed the Spanish cavalry opposite. d'Enghien himself was able to follow this up by attacking the exposed left flank of the Spanish infantry.

The battle was still inconclusive, with both armies having had success on their right and trouble on their left.

d'Enghien's "illumination de génie décide du sort de la journée"

d'Enghien, aware that his left and center were in trouble, decided that the best way to help them was not to fall back and support them, but rather to exploit his winning momentum on the right flank. He ordered a huge cavalry encirclement, achieved via a sweeping strike behind the Spanish army. d'Enghien and his cavalry soon smashed their way through to attack the rear of the Spanish cavalry on the right flank, which were still in combat with his reserves.[8]

The move succeeded; it was later called a "stroke of genius that decided the fate of the day" (literal translation), and asserted d'Enghien's reputation as a military leader.

The Spanish horse was routed, leaving the Spanish infantry to carry on the fight against the French on all sides. The Spanish artillery fled, leaving their guns to be captured by the French. The momentum now lay with the French army.

Concluding battle

Two French charges were repulsed by the Spanish tercios, but the infantry formations were forced to stand closer together to maintain their pike squares. d'Enghien arranged for his artillery and captured Spanish guns to blast them apart.

Soon the German and Walloon tercios fled from the battlefield, while the Spanish remained on the field with their commander, repulsing four more cavalry charges by the French and never breaking formation, despite repeated heavy artillery bombardment. d'Enghien finally offered surrender conditions just like those obtained by a besieged garrison in a fortress. Having agreed to those terms, the remains of the two tercios left the field with deployed flags and weapons.[9]

French losses were about 4,000. Melo stated his losses as 6,000 casualties and 4,000 captured in his report to Madrid written two days after the battle.[10] The estimates for the Spanish army's dead range from 4,000–8,000.[4] Of the 7,000 Spanish infantry only 390 officers and 1,386 enlisted men were able to escape back to the Spanish Netherlands.[4][11] Guthrie lists 3,400 killed and 2,000 captured for the five Spanish infantry battalions alone, while 1,600 escaped.[11] Most of the casualties of the battle were suffered by the Spanish infantry, while the cavalry and artillerymen were able to withdraw, albeit with the loss of all the cannons.[12]

Aftermath and significance

The French relieved the siege of Rocroi, but were not strong enough to move the fight into Spanish Flanders. The Spanish were able to regroup rapidly and stabilize their positions.[13] The year 1643 ended in a veritable stalemate, which was enough of a success for France.

Despite this, the battle was of great symbolic importance because of the high reputation of the Army of Flanders.[14] Melo in his report to the king called it "the most considerable defeat there has ever been in these provinces".

The successful show of strength was important for France. At home, it was seen as a good omen for the new king's reign, and secured the power of the regent queen and newly appointed cardinal Mazarin. While both Richelieu and Louis XIII had distrusted his wife the queen Anne of Austria (she was sister of Philip IV of Spain), when she became regent (until the 4 year old new king Louis XIV came of age), she confirmed Mazarin, Richelieu's protégé and political heir, as prime minister, and no change in politics occurred regarding the war.

It established the reputation of the 21-year-old French general Enghien, who later will be called "Grand Condé" ("grand" meaning "great") for his numerous victories.

Abroad, it showed that France remained as strong as before, despite its 4-year-old king. Supremacy in Europe was to move slowly from Habsburg Spain to Bourbon France in the decades to come. It was the new nature and weight of absolute monarchy in France which was now to encompass the decline of Habsburg Spanish imperial power in Europe.[15] Cardinal Mazarin was able to cope with the Fronde, then slowly to turn the tide against the Spanish in France and in the Low Countries. Mazarin's alliance with England resulted in the defeat of the Spanish at the Battle of the Dunes and consequently the taking of Dunkirk in 1658, prior to the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659. Although Spain looked to be all-powerful in 1652, the peace settlement reflected the demise of Spain's mastery of Europe in the late 1650s.[16]

It has been noted that Melo's German, Walloon, and Italian troops actually surrendered first, while the Spanish infantry surrendered only after standing hours of infantry and cavalry charges and a vicious spell under the French guns. They were given the treatment usually given to a fortress garrison and retired from the field with their arms, flags and honors.

In media

A 2006 Spanish movie, Alatriste, directed by Agustín Díaz Yanes, portrays this battle in its final scene. The soundtrack features in this scene a funeral march, La Madrugá, composed by Colonel Abel Moreno for the Holy Week of Seville, played by the band of the 9th Infantry Regiment “Soria”, heir of that which participated in the battle, the oldest unit in the Spanish Army, and since nicknamed "the bloody Tercio".

Museum

The sedan chair belonging to the elderly Spanish infantry general Paul-Bernard de Fontaines, who was suffering from gout[17] and was carried to battle in the chair, was taken as a trophy by the French and may be seen in the museum of Les Invalides in Paris. Fontaines (originally from the Spanish Netherlands - now Belgium - and known to the Spanish as de Fuentes) was killed in the battle; Enghien is reported to have said, "Had I not won the day I wish I had died like him".[18]

References

Citations

- Guthrie 2003, p. 185.

- Guthrie 2003, p. 174.

- John Childs (2006). Warfare in the Seventeenth Century. Smithsonian Books. p. 75. ISBN 006089170X.

- González de León 2009, p. 312.

- Guthrie 2003, p. 180.

- "The Works of Voltaire, Vol. XII (Age of Louis XIV) - Online Library of Liberty". oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Spanish Disaster at Rocroi". Warfare History Network. 14 October 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Iselin 1965, p. 149.

- Agustín Pacheco Fernández, Rocroi, el último tercio. Spain: Galland Books, 2011. pp. 15-17

- González de León 2009, p. 312–313.

- Guthrie 2003, p. 182.

- González de León 2009, p. 313.

- Jeremy Black European Warfare, 1494-1660, Psychology Press, 2002, p 147

- Jeremy Black European Warfare, 1494-1660, Psychology Press, 2002, p 147

- Perry Anderson (23 April 2013). Lineages of the Absolutist State (Verso World History Series). Verso Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-78168-054-4. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- William Young (1 September 2004). International Politics And Warfare In The Age Of Louis Xiv And Peter The Great: A Guide To The Historical Literature. iUniverse. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-595-32992-2. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Sanchez, Juan. "Paul Bernard de Fontaine (1576 - 1643), señor de Fougerolles, Conde del S.R.I." [Paul Bernard de Fontaine (1576 - 1643), Lord of Fougerolles, Count of the Holy Roman Empire] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "La bataille de Rocroi (1643)" [The battle of Rocroi (1643)] (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2017.

Bibliography

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-270056-1.

- González de León, Fernando (2009). The Road to Rocroi: Class, Culture and Command in the Spanish Army of Flanders, 1567–1659. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17082-7.

- Guthrie, William. P. (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32408-5.

- Stephane Thion (2013). Rocroi 1643: The Victory of Youth. Histoire et Collections. ISBN 978-2352502555.