Spanish missions in the Americas

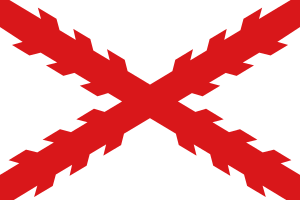

The Spanish missions in the Americas were Catholic missions established by the Spanish Empire during the 16th to 19th centuries in the period of the Spanish Colonization of the Americas. These missions flanked the entirety of the Spanish colonies, which extend from Mexico and southwestern portions of current-day United States to Argentina and Chile.

Part of a series on |

| Spanish missions in the Americas of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Missions in North America |

| Missions in South America |

| Related topics |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of New Spain |

|

|

The relationship between the Spanish Colonization and the Catholicization of the Americas is inextricable. The conversion of the region was crucial for the colonization of it. The missions that were built by members of Catholic orders were often created on the outermost borders of the colonies. This construction facilitated the expansion of the Spanish empire through the religious conversions of the indigenous peoples occupying those areas. While the Spanish Crown dominated the political, economic, and social realms of the Americas and those indigenous to the region, the Catholic Church dominated the religious and spiritual realm. Similar to the way that colonization requires destruction of what existed before in order to construct something new, the Catholicization of the Americas actively destroyed indigenous spiritualities. The Church and its clergy replaced indigenous gods, goddesses, and temples with Catholic churches and cathedrals, saints, and other practices. Quite often, indigenous peoples honored Catholic religious symbols in conjunction with symbols of their own spiritualities. One such example is Our Lady of Guadalupe, who is an image of the Virgin Mary, and is associated with the Aztec goddess Tonantzin.[1]

The evangelization of Catholicism was motivated by many conjoining desires and rationalizations. The Spanish Crown was interested in the spread of the Spanish Empire, and viewed the spread of the Catholic Church as a primary means to colonize the land and the indigenous people on it. The Catholic Church as an institution was interested in redeeming the souls of the indigenous Americans. They believed that they were given the divine right and responsibility of Christianizing as many parts of the world as possible. Missionaries themselves were motivated by the desire to construct the Americas as the site of pure Christianity, as a departure from European Christianity. Many religious clergy had become critical of the increasingly corrupt papacy in Europe, demanding excessive tribute and accepting monetary indulgences for redemption. Many clergy ventured to the Americas so they could preach what they felt was a purer form of Christianity, and to redeem the souls of the indigenous peoples. This paternalist viewpoint excused much of the violence and abuse experienced by the indigenous Americans at the hands of the colonizers, political elite and religious clergy alike.

To restate, the role of the Catholic Church is incredibly significant in the Spanish Colonization of the Americas. Despite extensive efforts in recovering the cultural history of indigenous cultures, much of the evidence currently available comes from the colonizers themselves and the missionaries, more specifically. Many of the cultures impacted by missionaries had no written language and were thus robbed of much of their oral history when the populations were decimated by Old World illnesses.[2] Cultures that indeed possessed written languages, such as the Maya, often had their artifacts deemed sacrilegious and burned.[3] Therefore, much of the history of Christian missions comes from accounts of missionaries and—to a much lesser extent archaeological investigation, and should be handled with care. Readers should consider the ethnocentric and theocratic context in which missionaries presented their accounts.

Beginnings of evangelization

Patronato Real

The Patronato Real, or Royal Patronage, was a series of papal bulls constructed in the 15th and early 16th Century that set the secular relationship between the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church, effectively pronouncing the Spanish King’s control over the Church in the Americas. It clarified the Crown’s responsibility to promote the conversion of the indigenous Americans to Catholicism, as well as total authority over the Church, educational, and charitable institutions. It authorized the Crown’s control over the Church’s tithe income, the tax levied on agricultural production and livestock, and the sustenance of the ecclesiastical hierarchies, physical facilities, and activities. It provided the Crown with the right to approve or veto Papel dispatches to the Americas, to ensure their adherence to the Patronato Real. It determined the founding of churches, convents, hospitals, and schools, as well as the appointment and payment of secular clergy.[1]

It is clear that the Patronato Real provided the Spanish Crown with an unprecedented level of authority over the Catholic Church. It demonstrates the intricate relationship the political expansion of the colonies had with Catholicism. As these bulls were discussed and granted prior to and in the early stages of Spanish Colonization, it is clear that the Catholic Church operated in the interests of the Spanish Crown from the start. The expansion of Catholic missions around the Americas afforded the Crown an increasing income from the levied taxes and control over tithe income. That economic interest—along with the Crown’s control over the Church’s educational and charitable institutions, which directly interacted with and deeply influenced a large swath of the indigenous populations they were colonizing—provided an argument for the Crown’s interest in incorporating the Catholic Church into their colonization of the Americas.

Parish expansion

To promote conversions, the Catholic Missionaries in the Americas received Royal approval to create provinces, or parishes. These parishes echoed the structures of European towns—created with the explicit intention of converting the indigenous peoples who constructed and lived in them. These territories were separate from the jurisdictions of the Crown, with separate laws and structures. The papacy sent multiple religious orders to set up towns in areas along the borderlands[4] to prevent a single order from becoming too powerful. First the Franciscans set up parishes, then the Dominicans, Augustinians, and Jesuits followed. These orders are discussed in more detail later on in this article.

To begin the process of constructing a new parish, the priests entered an indigenous village and first converted the leaders and nobles, called caciques. These conversions were often public. Once the caciques were converted, the clergy collaborated with the elites to construct a chapel, often atop the destroyed temple for the indigenous spirituality. This chapel played a role in bringing the rest of the people of the town to the Church. The Franciscans in particular wanted an indigenous priesthood, and built schools to teach indigenous elite about humanistic studies.

The clergy were most interested in converting the souls of the indigenous, by any means possible. Therefore, in many instances, the clergy used indigenous religions to gain trust and legitimacy. In fact, many members of the clergy learned indigenous languages so they could be more accessible and understandable to those wanted to convert. They even selected indigenous languages to be used as linga franca in areas that had linguistic diversity. In New Spain, which is modern-day Mexico and Central America, the friars taught Nahuatl to indigenous Americans who had not spoken it prior, as a way of establishing a common language. They translated hymns, prayers, and religious texts into Nahuatl to make Catholicism more widely spread and understood. The clergy in Peru used Quechua and Aymara in similar ways.[1]

Early into the existence of the community, the European clergy formed a cofradía, which is a lay brotherhood meant to raise funds to construct and support the parish church, provide aid to the poor, aged, or infirmed and to widows and orphans, and to organize religious processions and festivals for Catholic holidays.[5] That said, the creation of the parish also depended on the labor of the recently converted indigenous people to build schools, offices, houses, and other infrastructure for economic production. This need for labor led to conflict with the encomenderos, who were charged by the Crown with the exclusive task of exploiting indigenous labor.

Parish economy

The Catholic orders profited tremendously from the expansion of the parishes and from the conversion of the indigenous peoples, along with the exploitation of their labor. The Jesuits, among other orders, became extremely wealthy as a result. The Jesuits gained landholdings in the 17thcentury, becoming prominent property owners throughout the colonies. Unlike other methods used for property accumulation, like land seizure or royal grant, the Jesuits gained property from purchase and donation. The Jesuits also amassed wealth from tithes and clerical fees, as well as from profits made from the production of agricultural and other commercial products. The Jesuits, along with the other religious orders, fully participated in and profited off of the internal trade economy of the Americas.[1]

Therefore, the religious orders that had vowed themselves to poverty had become some of the wealthiest institutions in the Americas. All of this production was at the expense of the indigenous who were converted and colonized, as it was the indigenous people who completed the labor-based tasks. As we can see, the spread of Catholicism was highly profitable to the Catholic Church.

Paternalist protection

Much of the expressed goals of the spread of Catholicism was to bring salvation to the souls of the indigenous peoples. The Church and the Crown alike viewed the role and presence of the Church in the Americas as a buffer against the corrupt encomenderos and other European settlers. The Church and its clergy were meant to be advocates for the interests of the indigenous, as well as to provide them with social services. To do this, the indigenous parishes had different laws, different economies, different government styles, all with the intention of keeping them separate, and protected from the European society. The indigenous Americans were consideredby the Crown and the Church to be legal minors, so much of the motivation for this paternalism comes from the desire of the Church to protect their “children” from the harsh and corrupt Europeans.[1]

It is important here to point out an irony within this ideology and practice. While the Church and its clergy had the intention of protecting the indigenous peoples, it was also successfully exploiting their labor, profiting off of the production.

Spanish colonialism

Practices

Catholic missions were installed throughout the Americas in an effort to integrate native populations as part of the European culture; from the point of view of the Spanish Kings, naturals of America were seen as Crown subjects in need of care, instruction and protection from the military and adventurers, most of them in the pursuit of gold, silver, land and nobility titles. The missionaries goal was to convert natives to Christianity, because diffusion of Christianity was deemed to be a requirement of the religion. Spanish Vice-royalties in America had the same structure as the Vice-Royalties in Spanish provinces. The Catholic church depended on the Kings administratively, but in doctrine was subjected, as always, to Rome. Spain had a long battle with the Moors, and Catholicism was an important factor unifying the Spaniards against the Muslims. Further, the religious practices of American natives alarmed the Spanish, so they banned and prosecuted those practices. The role of missionaries was primarily to replace indigenous religions with Christianity, which facilitated integration of the native populations into the Spanish colonial societies.[6] One symbolic example of this was the practice of constructing churches and cathedrals, such as Santa Domingo and Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of the Assumption, on top of demolished native temples.[7] Establishment of missions was often followed by the implementation of Encomienda systems by the Vice-royal authorities, which forced native labor onto land granted to Europeans by the Spanish Crown and led to oppression.

Missionaries

Pedro de Gante was a European missionary who desired assimilation of Native American communities to further educational discourse amongst indigenous communities. He was so influential in his work, he became known as "The first teacher of the Americas".[8] Originally, Peeter Van der Moere, Pedro de Gante, came to New Spain, in 1523 also known as Mexico. A missionary, Pedro de Gante, wanted to spread the Christian faith to his native brothers and sisters. During this time, the mentality of the Spanish people proscribed empowering the indigenous people with knowledge, because they believed that would motivate them to retaliate against the Spanish rulers. Nevertheless, Pedro de Gante saw the ritualistic practices of the indigenous, which traditionally involved human sacrifices (specially from enemy tribes), and as a missionary, saw the need for a change in faith. He decided the best approach was to adapt to their way of life. He learned their language and participated in their conversations and games.[9] Despite having a stutter, he was a successful translator of Nahuatl and Spanish.[8] Additionally, Pedro de Gante was a big advocate of education of the youth, where he established schools throughout Mexico to cater to the indigenous communities.[10] His influence spanned so wide, others like him followed by example. Of the future missionaries to come to America, at least three of his compatriots came.[11]

Native revolts

In addition to the encomienda system, the aggressive implementation of missions and their forcible establishment of reductions and congregations led to resistance and sometimes revolt in the native populations being colonized. Many natives agreed to join the reductions and congregations out of fear, but many were initially still allowed to quietly continue some of their religious practices. However, as treatment of natives grew worse and suppression of native customs increased, so did the resistance of the natives.

The most notable example of rebellion against colonization is the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, in which the Zuni, Hopi, as well as Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos took control of Santa Fe and drove the Spanish colonial presence out of New Mexico with heavy casualties on the Spanish side, including 21 of the 33 Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico. The region remained autonomous under native control despite multiple non-violent attempts at peace treaties and trade agreements until 1692.

The Tepehuan Revolt was likewise stirred by hostilities against the missionaries, which arose due to the concurrent and explosive rise in disease that accompanied their arrival.[12] The Tepehuan associated the rise in death directly with these missionaries and their reductions, which spread disease and facilitated exploitative labor to encomanderos and miners.[13] The revolt lasted from 1616 to 1620 with heavy casualties on both sides. During the conflict, the Spanish abandoned their policy of "peace by purchase (tribute)" in favor of "war of fire and blood."[14]

Epidemics in missions

With resistance and revolts, the native population dropped drastically with the introduction of Spanish missions. However, the main factor for the overwhelming losses were due to epidemics in the missions. Despite being affected before the introduction of missions, the buildings allowed rodents to infiltrate living areas and spread disease more rapidly. Some of the most common diseases were typhus, measles and smallpox.[15] Many natives were living in cramped spaces with poor hygiene and poor nutrition. This led not only to high mortality rate, but to low fertility rates as well. In specific areas where natives were dispersed in various regions, friars created new villages to divide the natives from Europeans and simultaneously systemize their teachings.[16] It is estimated that every 20 years or so, a new epidemic wiped out the adult population of natives in many missions, giving no chance for recovery.[17] It is imperative, at this moment, to illustrate the loss of life in the Native population by using the example of the small province known as Jemez in New Mexico. Scientists say that upon the arrival of the Spanish missionaries in 1541, approximately 5,000 to 8,000 natives lived in Jemez. Through examination of plants within the village, scientists were able to determine the age gap of plant life to better understand the loss of human interaction with vegetation. By 1680, scientists concluded that the Jemez village was populated by approximately 850 natives. This 87% decrease in population size illustrates the tragic effects of diseases of the time, combined with the introduction of a new culture influenced by the Spanish missionaries. [18]

Cultural changes

In converting natives, missionaries had to find various ways of implementing sacramental practices among them. Some sacraments, like Baptism, were already similar to the Nahuatl rituals during birth, usually performed by a midwife. Many missionaries even allowed for natives to keep some aspects of their original ritual in place, like giving the child or newborn a small arrowhead or broom to represent their future roles in society, as long as it complied with Catholic beliefs. Other sacraments, like Matrimony, were fairly different from native practices. Many natives were polygamous. To perform the sacrament of marriage, Franciscan friars had a husband bring his many wives to the church, and had each state her reasons for being the one true wife. The friars then decided who was the wife, and performed the sacrament.[19]

In addition to religious changes, Spanish missionaries also brought about secular changes. With each generation of natives, there was a gradual shift in what they ate, wore and how the economy within the missions worked. Therefore, the younger generation of natives were the most imperative in the eyes of the Spanish mission. The missionaries began educating the native youth by separating the children from their families and placing them in Christian-based schooling systems. To reach their audience, the Spanish missionaries devoted much time to learning the native culture. This cultural shift can best be seen in the very first trilingual dictionary dating back to 1540 in Mexico. This book that was uncovered took the printed version of author Antonio Nebrija’s dictionary titled Grammar and Dictionary (focused on spanish and latin translations), and added handwritten translations of Nahuatl language within the document. Although the author of these edits is unknown, it is a tangible example of how Spanish missionaries began the process of catholic transformation in Native territories.[20] Missionaries introduced adobe style houses for nomadic natives and domesticated animals for meat rather than wild game. The Spanish colonists also brought more foods and plants from Europe and South American to regions that initially had no contact with nations there. Natives began to dress in European-style clothing and adopted the Spanish language, often morphing it with Nahuatl and other native languages.[21]

Catholic orders

Franciscan

Franciscan missionaries were the first to arrive in New Spain, in 1523, following the Cortes expeditions in Mexico, and soon after began establishing missions across the continents.[22][23] The Franciscan missionaries were split evenly and sent to Mexico, Tezcoco, Tlaxcala, and Tezcoco.[24]:138 In addition to their primary goal of spreading Christianity, the missionaries studied the native languages, taught children to read and write, and taught adults trades such as carpentry and ceramics. By 1532, approximately 5,000 native children were educated by the Franciscan missionaries in newly built monasteries spread throughout central Mexico. Many of these children resided in cities such as Cholula, Tlalmanalco, Tezcuco, Huejotzingo, Tepeaca, Cuahutitlan, Tula, Cuernavaca, Coyoacán, Tlaxcala and Acapistla. Pedro De Gante was recorded to have the largest class of approximately 600 natives in Mexico City.[24]:146 The first missionaries to arrive in the New World were Franciscan friars from the observant faction, which believed in a strict and limited practice of religion. Because the friars believed teaching and practicing can only be done through "meditation and contemplation," Franciscans were not able to convert as many people as quickly as the Spanish wanted. This caused strain between colonial governments and Franciscan friars, which eventually led to several friars fleeing to present day western Mexico and the dissolution of Franciscan parishes. Other issues also contributed to the dissolution of Franciscan parishes, including the vow of poverty and accusations from colonial governments. However, Spanish missions often used money from the King to fund missions. Having friars taking money was controversial within the church. In addition, the colonial government claimed missionaries were mistreating indigenous people working on the missions. On the other hand, the Franciscan missionaries claimed that the Spanish government enslaved and mistreated indigenous people. Present day efforts are to show where Franciscan missionaries protected the indigenous people from Spanish cruelties and supported empowering the native peoples.[25]

Jesuits

The Jesuits had a wide-spread impact between their arrival in the New World about 1570 until their expulsion in 1767. The Jesuits, especially in the southeastern part of South America, followed a widespread Spanish practice of creating settlements called "reductions" to concentrate the widespread native populations in order to better rule, Christianize, and protect the native populace.[26] The Jesuit Reductions were socialist societies in which each family had a house and field, and individuals were clothed and fed in return for work. Additionally, the communities included schools, churches, and hospitals, and native leaders and governing councils overseen by two Jesuit missionaries in each reduction. Like the Franciscans, the Jesuit missionaries learned the local languages and trained the adults in European methods of construction, manufacturing, and, to a certain extent, agriculture.[27] By 1732, there were thirty villages populated by approximately 140,000 Indians located from Northern Mexico down to Paraguay.[28] Spanish settlers were prohibited from living or working in reductions. This led to a strained relationship between Jesuit missionaries and the Spanish because in surrounding Spanish settlements people were not guaranteed food, shelter, and clothing.[29]

Another major Jesuit effort was that of Eusebio Kino S.J., in the region then known as the Pimería Alta – modern-day Sonora in Mexico and southern Arizona in the United States.[30]

Dominicans

The Dominicans were centralized in the Caribbean and Mexico and, despite a much smaller representation in the Americas, had one of the most notable histories of native rights activism. Bartolomé de las Casas was the first Dominican bishop in Mexico and played a pivotal role in dismantling the practice of "encomenderos",these laws were intended to prevent the exploitation and mistreatment of the indigenous peoples of the Americas by the encomenderos, by strictly limiting their power and dominion over groups of natives, with the establishment of the New Laws in 1542.[31]

See also

References

- Burkholder, Mark A., 1943- (2019). Colonial Latin America. Johnson, Lyman L. (Tenth ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-19-064240-2. OCLC 1015274908.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Impact of European Diseases on Native Americans – Dictionary definition of The Impact of European Diseases on Native Americans | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 1524–1579., Landa, Diego de (1978). Yucatan before and after the conquest. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486236223. OCLC 4136621.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Hämäläinen, Pekka; Truett, Samuel (2011). "On Borderlands". Journal of American History. 98 (2): 9–30. doi:10.1093/jahist/jar259.

- McAlister, Lyle (1984). "Instruments of Colonization: The Castilian Municipio". Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492-1700: 133–152.

- story "History of Spanish Colonial Missions | Mission Initiative" Check

|url=value (help). missions.arizona.edu. Retrieved 27 October 2017. - "Cathedral of Cusco City". www.qosqo.com. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- L. Campos. Gante, Pedro De. Detroit: Gale, 2007, 89.

- Lipp, Solomon. Lessons Learned from Pedro de Gante. American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. Hispania, 1947, 194.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Pedro de Gante. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1998.

- Proano, Agustin Moreno. The Influence of Pedro de Gante on South American Culture. Artes de Mexico: Margarita de Orellana, 1972.

- May), Gradie, Charlotte M. (Charlotte (2000). The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616 : militarism, evangelism and colonialism in seventeenth century Nueva Vizcaya. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0874806229. OCLC 44964404.

- May), Gradie, Charlotte M. (Charlotte (2000). The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616 : militarism, evangelism and colonialism in seventeenth century Nueva Vizcaya. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0874806229. OCLC 44964404.

- Powell, Phillip W. (1952). Soldiers, Indians, and Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550–1600. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wade, Lizzie. "New Mexico's American Indian population crashed 100 years after Europeans arrived." ScienceMag, 25 Jan. 2016, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/new-mexicos-american-indian-population-crashed-100-years-after-europeans-arrived. Accessed 14 Jan. 2020.

- Burkholder, Mark A., and Lyman L. Johnson. Colonial Latin America. 9th ed., Oxford University Press, 2014. Colonial Latin America. pg. 106

- Newson, Linda. "The Demographic Impact of Colonization." The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005.

- Wade, Lizzie. "New Mexico's American Indian population crashed 100 years after Europeans arrived." ScienceMag, 25 Jan. 2016, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/new-mexicos-american-indian-population-crashed-100-years-after-europeans-arrived. Accessed 14 Jan. 2020.

- Reilly, Penelope. The Monk and the Mariposa: Franciscan Acculturation in Mexico 1520–1550(2016).

- "Christianizing the Nahua." The Aztecs and the Making of Colonial Mexico, https://publications.newberry.org/aztecs/section_3_home.html. Accessed 14 Jan. 2020.

- Jackson, Robert H., and Edward D. Castillo. Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization : The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians. 1st ed. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico, 1995.

- Page, Melvin E (2003). Colonialism : an international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia. Sonnenburg, Penny M. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 418. ISBN 978-1576073353. OCLC 53177965.

- Higham, Carol L. (9 May 2016). "Christian Missions to American Indians". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.323. ISBN 9780199329175.

- Morales, Francisco (2008). "The Native Encounter with Christianity: Franciscans and Nahuas in Sixteenth-Century Mexico". The Americas. 65 (2): 137–159. doi:10.1353/tam.0.0033. JSTOR 25488103.

- Schwaller, John F. (October 2016). "Franciscan Spirituality and Mission in New Spain, 1524–1599: Conflict Beneath the Sycamore Tree (Luke 19:1–10) by Steven E. Turley (review)". The Americas. 73 (4): 520–522. doi:10.1017/tam.2016.85.

- Caraman, Philip (1976), The lost paradise: the Jesuit Republic in South America, New York: Seabury Press.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Reductions of Paraguay". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Burkholder, Mark A., and Lyman L. Johnson. Colonial Latin America. 9th ed., Oxford University Press, 2014. Colonial Latin America. pg. 109

- "Bartolome de Las Casas | Biography, Quotes, & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Whitaker, Arthur P. (1982). "Rim of Christendom: A Biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific Coast Pioneer Herbert Eugene Bolton Eusebio Francisco Kino". Pacific Historical Review. 6 (4): 381–383. doi:10.2307/3633889. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3633889.

- "Bartolome de Las Casas | Biography, Quotes, & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Logan Wagner, E. The Continuity of Sacred Urban Open Space: Facilitating the Indian Conversion to Catholicism in Mesoamerica. Austin: Religion and the Arts, 2014.

- Yunes Vincke, E. "Books and Codices. Transculturation, Language Dissemination and Education in the Works of Friar Pedro De Gante." Doctoral Thesis (2015): Doctoral Thesis, UCL (University College London). Web.