Siege of Carthage (Third Punic War)

The Siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War between the Punic city of Carthage in Africa and the Roman Republic. It was a siege operation, starting sometime in 149 or 148 BC, and ending in spring 146 BC with the sack or razing and complete demolition of the city of Carthage by the Romans.

Background

After the Second Punic War, Carthage had grown very wealthy because of its trade, and also because it no longer had to maintain a mercenary army, one of the stipulations of the peace signed with the Romans after the last war. Growing Carthaginian anger with the Romans, who refused to lend help when the Numidians began annexing Carthaginian land, led them to declare war. Hasdrubal the Boetharch was appointed general of the army.

Siege

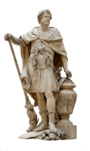

Unfortunately for Carthage, even before the arrival of the Romans, its Libyan allies began to revolt over the unfair treatment and the unfairness of how they had suffered during the previous wars against Rome, with many of towns and cities in Libya facing financial ruin from its constant wars with Rome. Many of the Libyan subjects and soldiers of Carthage now saw a chance to enrich themselves at the expense of their Carthaginian masters and as such duly revolted.[5] After a Roman army under Manius Manilius landed in Africa in 149 BC, Carthage surrendered, handed over its hostages and arms, and arrested Hasdrubal. The Romans demanded the complete surrender of the city. When asked what they planned on doing to the city, the Roman general told the diplomats that the city would be destroyed and its inhabitants would be relocated 50 miles inland. Surprisingly to the Romans, the city refused to surrender; the faction which advocated surrender was overruled by one vote in favor of defense.[6] The Carthaginians manned the walls and defied the Romans, a situation which lasted two years. During this period, the 500,000 Carthaginians behind the wall transformed the city into a huge arsenal. They produced a daily supply of about 300 swords, 500 spears, 140 shields, and over 1,000 projectiles for catapults.[3] The Romans elected the young and popular Scipio Aemilianus as consul, after a special law was passed in order to lift the age restriction. Scipio restored discipline, defeated the Carthaginians at Nepheris and besieged the city closely, constructing a mole to block the harbour.[7]

In the spring of 146 BC, Scipio and the Roman troops seized the Cothon wall of Carthage. They then battled their way through the double city harbors, which was made possible by the fact that Hasdrubal had assumed that the Roman attack would come from another direction. When day broke, 4,000 fresh Roman troops led by Scipio attacked the Byrsa, the strongest part of the city. Three streets lined with six story houses led to the Byrsa fortress and the Carthaginians and Romans fought each other from the rooftops of the buildings as well as in the streets. The Romans used captured buildings to capture other buildings. Scipio ordered the houses to be burned while their defenders were still inside. Scipio then captured the Byrsa and immediately set fire to the buildings, which caused even more destruction and deaths. The fighting continued for six more days and nights, until the Carthaginians surrendered. An estimated 50,000 surviving inhabitants were sold into slavery and the city was then levelled. The land surrounding Carthage was eventually declared ager publicus (public land) and shared between local farmers and Roman and Italian colonists.[8]

During the siege, 900 survivors, most of them Roman deserters, had found refuge in the temple of Eshmun, in the citadel of Byrsa, although it was already burning. They tried to negotiate a surrender but Scipio Aemilianus declared that forgiveness was impossible either for Hasdrubal, the general who defended the city or the defectors. Hasdrubal left the Citadel to surrender and pray for mercy (he had tortured Roman prisoners in front of the Roman army).[9] At that moment Hasdrubal's wife allegedly went out with her two children, insulted her husband, sacrificed her sons and jumped with them into a fire that the deserters had started.[10]

The deserters hurled themselves into the flames, upon which Scipio Aemilianus began weeping.[10] He recited a sentence from Homer's Iliad, a prophecy about the destruction of Troy, that could be applied to Carthage.[11] Scipio declared that the fate of Carthage might one day be Rome's.[12][13] In the words of Polybius:

Scipio, when he looked upon the city as it was utterly perishing and in the last throes of its complete destruction, is said to have shed tears and wept openly for his enemies. After being wrapped in thought for long, and realizing that all cities, nations, and authorities must, like men, meet their doom; that this happened to Ilium, once a prosperous city, to the empires of Assyria, Media, and Persia, the greatest of their time, and to Macedonia itself, the brilliance of which was so recent, either deliberately or the verses escaping him, he said:

A day will come when sacred Troy shall perish,

And Priam and his people shall be slain.And when Polybius speaking with freedom to him, for he was his teacher, asked him what he meant by the words, they say that without any attempt at concealment he named his own country, for which he feared when he reflected on the fate of all things human. Polybius actually heard him and recalls it in his history.[14]

Historians' views

Since the 19th century, various historians have claimed that the Romans ploughed over the city and sowed salt into the soil after destroying it but this is not supported by ancient sources.[15] Certain scholars, including Professor of History Ben Kiernan, allege that the total destruction of Carthage by the Romans may have been history's first genocide.[16][17]

Aftermath

The aftermath of the war would lead to Rome becoming one of the greatest expansionist powers in the Mediterranean as it was buoyed by its defeat of Carthage. The viciousness of the sack of Carthage could also be attributed to the actions of Hannibal the Carthaginian General who had defeated the Romans several times during the Second Punic War. Therefore it can be concluded that the sack of Carthage by the Romans was done as an act of revenge. The sudden Roman expansionism would also lead the Romans into a multitude of wars with the other powers in the Mediterranean, in particular the Greek city states and Macedon.

Notes

- Appian

- Tucker, Spencer (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-598-84429-0.

- Appian of Alexandria, The Punic Wars, ""

- Dutton, Donald G. (2007). The Psychology of Genocide, Massacres, and Extreme Violence: Why "normal" People Come to Commit Atrocities. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 14. ISBN 978-0275990008.

- "truceless war".

- Goldworthy pp. 338–339

- Goldworthy pp. 346–349

- Appian The Punic Wars

- Appian, Punica 118

- Appian of Alexandria,The Punic Wars, "The Third Punic War"

- Homer: Iliad; book 6

- Polybius: Histories, Book XXXVIII, Excidium Carthaginis, 7–8 and 20–22. English translation and comments by W. R. Patton. Loeb classical library, 1927, pp. 402–409 and 434–438.

- Online text of Polybius Histories

- Polybius XXXVIII, 20–22 The Fall of Carthage

- Ridley, R.T. (1986). "To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 81 (2): 140–146. doi:10.1086/366973. JSTOR 269786.

- Kiernan, Ben (2004-08-01). "The First Genocide: Carthage, 146 BC". Diogenes. 51 (3): 27–39. doi:10.1177/0392192104043648. ISSN 0392-1921.

- Rubinstein, William D. (2014). Genocide. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781317869962.

References

- Duncan B. Campbell, "Besieged: siege warfare in the ancient world", Osprey Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1-84603-019-6, pages 113–114

- Goldworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage (2000) London: Phoenix. ISBN 9780304366422