Second Punic War

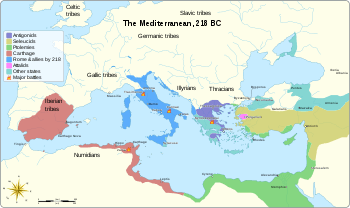

The Second Punic War (spring 218 – 201 BC),[3][4] also referred to as The Hannibalic War and by the Romans the War Against Hannibal, was the second of three Punic Wars between the Roman Republic and Carthage, with the participation of Macedonia and Syracuse polities and Numidian and Iberian forces on both sides. It was one of the deadliest human conflicts of ancient times. Fought across the entire Western Mediterranean region for 17 years and regarded by Livy as the greatest war in history, it was waged with unparalleled resources, skill, and hatred.[5]:21.1 It saw hundreds of thousands killed, some of the most lethal battles in military history, the destruction of cities, and massacres and enslavements of civilian populations and prisoners of war by both sides.

| Second Punic War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Punic Wars | |||||||||

The Mediterranean in 218 BC | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Aetolian League Pergamon Numidia Iberian tribes Celtiberian tribes |

Ancient Ligurian kingdoms Syracuse Masaesyli Massylii Other Greek states Iberian tribes Celtiberian tribes | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Scipio Africanus Fabius Cunctator M. Claudius Marcellus † Publius Cornelius Scipio † Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio † Gaius Claudius Nero Ti. Sempronius Longus Gaius Terentius Varro Masinissa of Numidia |

Syphax (POW) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

768,500[1] • 54,000 active Roman soldiers • 53,500 Roman capital detail • 388,000 Socii • 273,300 Reserves | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

500,000 dead (300,000 killed in action) 400 towns destroyed | 270,000 dead | ||||||||

| 770,000 dead[2] | |||||||||

| The Romans enslaved 14 Italian and Sicilian towns and massacred the entire population of two other towns. | |||||||||

The war began with the Carthaginian general Hannibal's conquest of the pro-Roman Iberian city of Saguntum in 219 BC, prompting a Roman declaration of war on Carthage in the spring of 218. Hannibal surprised the Romans by marching his army overland from Iberia to cross the Alps and invade Roman Italy, followed by his reinforcement by Gallic allies and crushing victories over Roman armies at the battles of Trebia in 218 and Lake Trasimene in 217. Moving to southern Italy in 216, Hannibal annihilated the largest army the Romans had ever assembled, at the Battle of Cannae. After the death or imprisonment of 130,000 Roman troops in two years, 40% of Rome's Italian allies defected to Carthage, giving it control over most of southern Italy. As Syracuse and Macedonia joined the Carthaginian side after Cannae, the conflict spread to Sicily and triggered the First Macedonian War in Greece. From 215–210 the Carthaginian army and navy launched repeated amphibious assaults to capture Roman Sicily and Sardinia, but were ultimately repulsed.

Against Hannibal's skill on the battlefield, the five-time consul Fabius Maximus organised a war of attrition against him, while fighting his allies and the other Carthaginian generals. Roman armies slowly recaptured most of the cities that had joined Carthage and defeated a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at Metaurus in 207. Southern Italy was devastated by the combatants, with hundreds of thousands of civilians killed or enslaved. In Iberia, which served as a major source of silver and manpower for the Carthaginian army, Roman operations were led by members of the Cornelii Scipiones. In 209, Publius Cornelius Scipio captured Carthago Nova, then won a streak of great victories, notably at Ilipa in 206, which permanently ended Carthaginian rule in Iberia. He invaded Carthaginian Africa in 204, inflicting two severe defeats on Carthage and her allies at Utica and the Great Plains that compelled the Carthaginian senate to recall Hannibal's army from Italy. The final engagement between Scipio and Hannibal took place at Zama in Africa in 202 and resulted in Hannibal's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on the Punic city. As a result, Carthage ceased to be a great power and became a Roman client state until its final destruction by Scipio Aemilianus in 146 BC during the Third Punic War. The Second Punic War overthrew the established balance of power of the ancient world and Rome rose to become the dominant power in the Mediterranean Basin for the next 600 years.

Background

Carthage's defeat in the First Punic War meant the loss of Carthaginian Sicily to Rome under the terms of the Roman-dictated 241 BC Treaty of Lutatius.[6] Rome exploited Carthage's distraction during the Truceless War against rebellious mercenaries and Libyan subjects to break the peace treaty and annex Carthaginian Sardinia and Corsica to Rome in 238 BC.[6] Under the leadership of Hamilcar Barca and his family, Carthage defeated the rebels and began the Barcid conquest of Hispania from 237 BC onward.[6][7] Control over Spain gave Carthage the silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards and territorial depth to stand up to future Roman demands with confidence.[8]

Destruction of Saguntum

Events leading to the war began with a decision by Hannibal, the new commander of troops in the Carthaginian province of Iberia, to consolidate power by provoking and defeating the surrounding Iberian tribesmen in battle. He was 26 years old. He had been voted commander by the army in Iberia on the assassination of the previous commander, Hasdrubal, in 221 BC. Hasdrubal had ruled by diplomacy rather than by victory. The military commander was also the provincial governor. He did not need the permission of the Carthaginian Senate to conduct operations.[9]

From 226 BC, the Romans and Carthaginians were bound by a treaty specifying the Ebro River as the boundary between the two interests. The Romans were not to operate south of it nor the Carthaginians north. An exception was made for the large town of Saguntum, whose ruins are located just north of Valencia, south of the Ebro. It was to be neutral. At some unspecified time, Rome had made a separate treaty with it. This made it a key element to Carthage, but not Rome.

Having subdued all the tribes south of the Ebro, Hannibal undertook the siege of Saguntum in 219 BC with 15,000 men.[note 1] After holding out for several months, Saguntum sent envoys to Rome asking for assistance. These arrived at the beginning of the consulships of Publius Cornelius and Tiberius Sempronius, who took office on March 15, 218 BC.[note 2] After hearing from the envoys, the Roman Senate resolved to send Publius Valerius Flaccus and Quintus Baebius Tamphilus to Hannibal at Saguntum to demand that he cease and desist. Being turned back by him at the coast, they went on to Carthage to lodge a criminal complaint of treaty violation with the Carthaginian Senate and demand the arrest of Hannibal and his extradition to Rome. The complaint was rejected. The two envoys returned to Rome just in time to hear the news that Saguntum had fallen and was destroyed; nearly all of the population had been executed and all the moveable wealth had been removed to Carthage.[10]

Declaration of war

"The effect on the Roman Senate was shattering", wrote Livy.[11] "They knew they had never had to face a fiercer or more warlike foe... War was coming, and it would have to be fought in Italy, in defence of the walls of Rome, and against the world in arms." They passed a decree to raise six legions: 24,000 infantry with 1,800 cavalry and enlist 40,000 allied infantry and 4,400 cavalry; they also had on hand 220 quinqueremes and 20 light ships.[12] Then they called an assembly of all free Romans to vote on the question of war.[note 3] The vote was for war. Tiberius was to take two legions to Sicily and wait there for orders to invade Carthage; Publius was given another two legions and tasked with attacking the Carthaginian forces in Iberia. The aged but experienced Lucius Manlius was given the praetorship of two more legions to be kept in reserve in Cisalpine Gaul, where issues with the Gauls were beginning to develop. Each force of two legions was supported by greater numbers of Italian and other allied troops.

The Senate now sent a delegation of "all oldish men – Quintus Fabius Maximus, Marcus Livius, Lucius Aemilius, Gaius Licinius, and Quintus Baebius" with plenipotentiary powers: the right to withhold or declare war on an ad hoc basis. Having brought copies of past treaties, they asked the Carthaginian Senate to determine if Hannibal had acted as an individual or with the approval of the Senate. The Carthaginians denied that Rome had a treaty with Carthage, pointing out that they had repudiated the Ebro Treaty, claiming that it was unratified, in order to make another with Saguntum, which had previously been defined as neutral.

Livy gives a romanced account of the debate in the Carthaginian senate. After hours of study and debate, nothing could be resolved concerning Hannibal's legality. Fabius gathered a fold of his toga to his chest and offered it, saying "Here, we bring you peace and war. Take which you will." The Carthaginians replied "Whichever you please – we do not care." Fabius let the fold drop and proclaimed "We give you war." The senators shouted "We accept it; and in the same spirit we will fight it to the end."[13]

The delegation returned through Spain, trying to encourage the tribes to revolt with little success, as Rome had lost credibility by failing to assist Saguntum. In Gaul, they were shouted down by assemblies of derisive citizens in full armor.

Carthaginian strategy and aims

The highest priority in Carthaginian strategy was to keep the war away from Carthage's agricultural heartland in Africa and protect the property of the wealthy Carthaginian landowners who controlled Carthaginian politics.[8] Spanish mines and sources of manpower comprised the second pillar of the Carthaginian power base and their protection was essential to maintaining Carthage's status as an independent continental great power.[14] Hannibal's invasion of Italy forced the Romans to abandon their intended invasion of Africa and de-prioritize the reinforcement of Roman armies in Spain. Most Roman troops during the war fought in Italy, which became the main theater of the war as a result of Hannibal's offensive.[15] Africa remained undisturbed by a Roman invasion army until 204 BC and the Roman military presence in Spain was confined to its northeastern corner until 209 BC. The continuation of Carthaginian rule in Africa and Spain enabled her to mobilize more armies and fleets, attempt the reconquest of Sicily and Sardinia from 215 to 210 BC and further invade Italy with Hasdrubal Barca's army in 208 BC and with Mago Barca's forces from 205 to 203 BC.[16]

To win the war, Hannibal in Italy sought to build up a united front of the northern Italian Gallic tribes and south Italian city states to encircle Rome and confine it to central Italy, where it would pose a lesser threat to Carthage's power-political freedom of action.[17][18] A Carthaginian protectorate over Italy would be created, enforced by the presence of Carthaginian soldier colonists and the Carthaginian annexation of parts of Italy.[17][18] This would act as a check on Roman revanchism.[18] Sicily and Sardinia were also to be regained for Carthage by sending expeditionary forces and allying with anti-Roman rebels on both islands.[19]

Course of the war

Beginning of the war (218–217 BC)

The Carthaginian army in Spain under Hannibal marched from New Carthage (Cartagena, Spain) northwards along the coast in May or June of 218 BC, subduing the tribes between the Ebro river and the Pyrenees. Hannibal then entered Gaul and took his army by an inland route, avoiding the Roman allies along the coast.[20] At the Battle of Rhone Crossing, Hannibal defeated a force of the Allobroges that sought to bar his way.[21] A Roman fleet under the command of the brothers Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus and Publius Cornelius Scipio with an invasion force intended for northern Spain landed at Rome's ally Massalia by the Rhone river.[22] Hannibal evaded the Romans and by an unknown route reached the Isère or the Durance at the foot of the Alps in autumn.[20] Gnaeus Scipio continued to Iberia with the Roman army.[23][24] The other commander, Publius Scipio, returned to Rome, realizing the danger of an invasion of Italy where the tribes of the Boii and Insubres were already in revolt.[24] After 217 BC, he moved to Iberia.[24]

Spain (218–217 BC)

Gnaeus Scipio landed his army at Cissa and won increasing support among the natives.[23] The Carthaginian commander in the area, Hanno, refused to wait for Carthaginian reinforcements under Hasdrubal, attacked Scipio at the Battle of Cissa in late 218 BC and was defeated.[23][24] The combined Roman and Massalian fleet and army posed a threat to the Carthaginians. In 217 BC, Hasdrubal moved up to engage them at the Battle of Ebro River. The 40 Carthaginian and Iberian vessels were severely defeated by the 55 Roman and Massalian ships in the second naval engagement of the war, with 29 Carthaginian ships lost. In the aftermath, the Carthaginian forces retreated, but the Romans remained confined to the area between the Ebro and Pyrenees.[24]

Italy (218–217 BC)

In 218 BC, the Carthaginian navy was scouting Sicilian waters and preparing for a surprise attack on their former key stronghold of Lilybaeum on the western tip of the island. Twenty quinqueremes, loaded with 1,000 soldiers, raided the Aegadian Islands west of Sicily and eight ships intended to attack the Aeolian Islands, but were blown off-course in a storm towards the Straits of Messina. The Syracusan navy, then at Messina, captured three of those without resistance. Learning from their crews that a Carthaginian fleet was to attack Lilybaeum, Hiero II warned the Roman praetor Marcus Amellius there. As a result, the Romans prepared 20 quinqueremes, which intercepted and defeated the 35 Carthaginian quinqueremes in the Battle of Lilybaeum. Subsequently, consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus sailed with a fleet from Lilybaeum and captured the island of Malta from the Carthaginians without much of a fight.

In Cisalpine Gaul, the Gallic Boii and Insubres rebels attacked the Roman colonies of Placentia and Cremona, causing the Romans to flee to Mutina (modern Modena), which the Gauls then besieged. A Roman relief army under Praetor L. Manlius Vulso raised the siege but was ambushed and besieged itself.[25] The Roman Senate sent one of Scipio's legions and 5,000 allied troops to aid Vulso. Scipio had to raise fresh troops to replace these and thus could not set out for Iberia until September 218 BC, giving Hannibal time to march from the Ebro to the Rhone.[26]

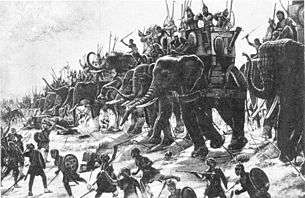

Hannibal crossed the Alps, surmounting the difficulties of climate and terrain,[20] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes. His exact route is disputed. Hannibal arrived with either 20,000 or 28,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants in the territory of the Taurini, in what is now Piedmont, northern Italy.[27][28] The Romans had not anticipated such an early arrival and their forces were still in their winter quarters.[5]:21.32–38 His surprise entry into the Italian peninsula led to the termination of Rome's main intended thrust, an invasion of Africa.[26]

Hannibal's first action was to take the chief city of the hostile Taurini (in the area of modern-day Turin). Hannibal's army then routed the cavalry and light infantry of the Romans under Publius Scipio at the Battle of Ticinus.[29] As a result of Rome's defeat at the Ticinus, all the Gauls except the Cenomani were induced to join the Carthaginian cause, bolstering Hannibal's army to at least 40,000 men.[30] Even before news of the defeat at the river Ticinus had reached Rome, the Senate had ordered the consul Sempronius Longus to bring his army back from Sicily, where it had been preparing for the invasion of Africa, to join Scipio and face Hannibal.[30] The united Roman force under the command of Sempronius Longus was lured into combat by Hannibal at the Battle of the Trebia. Hannibal's army encircled and destroyed the unprepared Romans.[31] Only 10,000 Romans out of 42,000 were able to retreat to safety. Having secured his position in northern Italy by this victory, Hannibal quartered his troops for the winter among the Gauls. The latter joined his army in large numbers, bringing it up to 60,000 men.[30]

The Roman Senate resolved to raise new armies against Hannibal under the recently elected consuls of 217 BC, Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius.[5]:21.63 To block Hannibal's advance into central Italy, Flaminius moved his army from Ariminum to Arretium, to cover the Apennine mountain passes into Etruria. His colleague Servilius deployed his freshly raised army at Ariminum to cover the route along the Adriatic coast. A third force, containing the survivors of previous engagements, was also stationed in Etruria under Scipio.[32]

In early spring 217 BC, Hannibal decided to advance, leaving his wavering Gallic allies in the Po Valley, and crossed the Apennines unopposed. He avoided the Roman positions and took the only unguarded route into Etruria at the mouth of the Arno. This route was through a huge marsh, which happened to be more flooded than usual for spring. Hannibal's army marched for several days without finding convenient places to rest, suffering terribly from fatigue and lack of sleep. This led to the loss of part of the force, including, it seems, the few remaining elephants.

Arriving in Etruria, still in the spring of 217 BC, Hannibal tried without success to draw the main Roman army under Flaminius into a pitched battle by devastating the area the latter had been sent to protect.[33] Hannibal then employed a new stratagem, when he marched around his opponent's left flank and effectively cut him off from Rome. Advancing through the uplands of Etruria, the Carthaginian now provoked Flaminius into a hasty pursuit without proper reconnaissance.[34] Then, in a defile on the shore of Lake Trasimenus, Hannibal lay in ambush with his army.[34] The ambush was a complete success: in the battle of Lake Trasimene Hannibal destroyed most of the Roman army and killed Flaminius with little loss to his own army.[34] 6,000 Romans had been able to escape, but were caught and forced to surrender by Maharbal's Numidians. Furthermore, Geminus, aware of the fighting, sent his 4,000 cavalry in support, but it was also caught in Umbria and annihilated. Like after all previous engagements, the captured enemies were sorted according to whether they were Romans, who were held captive, or non-Romans, who were released to spread the propaganda that the Carthaginian army was in Italy to fight for their freedom against the Romans. Strategically, Hannibal had now disposed of the only field force that could check his advance on Rome but he did not attack the city. Instead, he marched to the south in the hope of winning over allies amongst the Greek and Italic population there.[32]

The defeat at Lake Trasimene put the Romans in an immense state of panic, fearing for the very existence of their city. The Senate decided to appoint Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator. The Senate also appointed his magister equitum ("master of cavalry", who acted as his second-in-command): Marcus Minucius Rufus.[5]:22.8

Fabius invented the Fabian strategy of avoiding open battle with his opponent, but constantly skirmishing with small detachments of the enemy. This course was not popular among the soldiers, earning Fabius the nickname Cunctator ("delayer"), since he seemed to avoid battle while Italy was being burned by the enemy.[32] Having ravaged Apulia without provoking Fabius into a battle, Hannibal decided to march through Samnium to Campania, one of the richest and most fertile provinces of Italy, hoping that the devastation would draw Fabius into battle. As the year wore on, Hannibal decided that it would be unwise to winter in the already devastated plains of Campania but Fabius had ensured that all the mountain passes offering an exit were blocked. This situation led to the night battle of Ager Falernus in which the Carthaginians made good their escape by tricking the Romans into believing that they were heading to the heights above them.[35] This was a severe blow to Fabius’ prestige.[32]

Minucius, the magister equitum, was one of the leading voices in the army against the adoption of the Fabian Strategy. As soon as he scored a minor success, by winning a skirmish with the Carthaginians near Geronium, the Senate promoted Minucius to the same imperium (power of command) as Fabius, whom he accused of cowardice. In consequence, the two men decided to split the army between them. Minucius' troops were swiftly lured into an ambush and decimated by Hannibal at the Battle of Geronium. Fabius rushed to his co-commander's assistance and Hannibal's forces immediately retreated. Subsequently, Minucius accepted Fabius' authority and ended their political conflict.[32]

Carthaginian ascendancy (216–215 BC)

Italy (216–215 BC)

Fabius became unpopular in Rome, since his tactics did not lead to a quick end to the war. The Roman populace derided the Cunctator, and at the elections of 216 BC elected as consuls Gaius Terentius Varro who advocated pursuing a more aggressive war strategy and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, who advocated a strategy in the middle between the Fabian tactics and the tactics suggested by Varro.[36]

In the campaign of 217 BC, Hannibal had failed to obtain a following among the Italics. In the spring of 216 BC, he took the initiative and seized the large supply depot at Cannae in the Apulian plain. The Roman Senate authorized the raising of double-sized armies by the consuls Varro and Aemilius Paullus, a force of 86,000 men, the largest in Roman history up to that point.[36]

The consuls Aemilius Paullus and Varro resolved to confront Hannibal and marched southward to Apulia. After a two-day march, they found him on the left bank of the river Aufidus, and encamped 10 km (6.2 mi) away. Hannibal capitalized on Varro's eagerness and drew him into a trap by using an envelopment tactic that eliminated the Roman numerical advantage by shrinking the surface area where combat could occur.[34] Hannibal drew up his least reliable infantry in the centre of a semicircle, with the wings composed of the Gallic and Numidian horse.[34] The Roman legions forced their way through Hannibal's weak centre, but the Libyan Mercenaries on the wings swung around their advance, menacing their flanks.[35] The onslaught of Hannibal's cavalry was irresistible, and the cavalry commander Hasdrubal[5]:22.45[37][38] (not to be confused with Hannibal's brother who was campaigning in Iberia[5]:23.26[39][40]), routed the Roman cavalry on the Roman right wing and then swept around the rear of the Roman line and attacked Varro's cavalry on the Roman left, and then the legions, from behind.[35] As a result, the Roman army was surrounded with no means of escape.[35] Due to these brilliant tactics, Hannibal, with much inferior numbers, managed to destroy all but a small remnant of this force.[35] At least 67,500 Romans were killed or captured at Cannae.

Livy notes, "How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those which preceded it can be seen by the behaviour of Rome's allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman power."[5]:22.61[41] During that same year, the Greek cities in Sicily were induced to revolt against Roman political control, while the Macedonian king, Philip V, pledged his support to Hannibal – thus initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome. Hannibal also secured an alliance with newly appointed King Hieronymus of Syracuse, and Tarentum also came over to him around that time. Hannibal refused to attack Rome after Cannae. The Romans looked back on Hannibal's indecision as what saved Rome from certain defeat. Hannibal merely sent a delegation to Rome to negotiate a peace and another one offering to release his Roman prisoners of war for ransom, but Rome rejected all offers.[42]

After Cannae, several south Italian cities allied themselves to Hannibal: the Apulian towns of Salapia, Arpi and Herdonia and many of the Lucanians. Mago marched south with a Carthaginian army detachment and, some weeks later, the Bruttians joined him. Simultaneously, Hannibal marched north with part of his forces and was joined by the Hirpini and the Caudini, two of the three Samnite cantons. The greatest gain was the second largest city of Italy, Capua, when Hannibal's army marched into Campania in 216 BC. The inhabitants of Capua held limited Roman citizenship and the aristocracy was linked to the Romans via marriage and friendship, but the possibility of becoming the supreme city of Italy after the evident Roman disasters proved too strong a temptation. The treaty between them and Hannibal can be described as an agreement of friendship, since the Capuans had no obligations, but provided the harbour through which Hannibal was reinforced.[43]

In 216 BC, another disaster struck Rome as the consul-elect for 215, Lucius Postumius Albinus was ambushed along with his 25,000 soldiers by Boii Gauls northwest of Ariminum at the Battle of Silva Litana. Postumius had been tasked with harassing the pro-Carthaginian Gallic tribes and forcing them to retreat back to the Po Valley. The Roman army was slaughtered and Postumius killed. The news triggered renewed panic in Rome.[44]

By 215 BC, Hannibal's alliance system covered the bulk of southern Italy, save for the Greek cities along the coast (except Croton, which was conquered by his allies), Rhegium, and the Latin colonies of Beneventum, Luceria in Samnium, Venusia in Apulia, Brundisium and Paestum.[45] The independent Gaul he had established in northern Italy was still out of Roman control.[46]

The port city of Locri defected to Carthage in the summer of 215 and was immediately used to build up the Carthaginian forces in Italy with cavalry, war elephants, silver and grain.[47] It was the only time during the war that Carthage succeeded in sending reinforcements to Hannibal in Italy. A second force in 215, under Mago, consisting of 12,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry and 20 elephants guarded by 60 warships, was also meant to land in Italy but bolstered Hasdrubal in Spain instead after the Carthaginian defeat there at Dertosa.[48]

Hannibal had been able to win over a major allied base by his tremendous military success. He also regarded it as essential to take the city of Nola, a Roman fortress in Campania, a region that linked his various allies geographically and contained his most important harbour for supply. Prior to his first attempt, the pro-Carthage faction in the city had been eliminated by the Romans, so there was no chance of the city being betrayed. Hannibal repeatedly tried to take this city by assault or siege, but was thwarted three times, in 216, 215 and 214, by forces led by Marcus Claudius Marcellus. In 215, Hannibal besieged and starved Casilinum into submission, the other important site for controlling Campania.[49]

The first Carthaginian expedition to Sardinia, in 215 BC, was under the command of Hasdrubal The Bald with his Punic-Sardinian subordinate Hampsicora.[50] A previous pro-Carthaginian uprising had been defeated, while a storm had blown the Carthaginian fleet to the Balearic Islands.[5]:23.24 When they finally arrived at Sardinia, the Romans were aware of their intentions and had reinforced the unpopular garrison under Titus Manlius Torquatus to 20,000 infantry and 1,200 cavalry. These engaged and defeated the Carthaginians' 12,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry (plus an unknown number of elephants) and the remaining insurgent Sardinians at the Battle of Cornus. In the aftermath, the defeated expedition of 60 quinqueremes and several transports encountered a Roman raiding party from Africa with 100 quinqueremes. The Carthaginian fleet scattered and escaped save for seven ships. As a result, Sardinia, an important grain exporter, remained under Roman occupation.

Spain (215 BC)

The Roman army in Spain prevented the Carthaginians from sending reinforcements from Iberia to Hannibal or to the insurgent Gauls in northern Italy during critical stages of the war.[24] Hasdrubal received orders from Carthage to move into Italy and join up with Hannibal to put pressure on the Romans in their homeland.[24] Hasdrubal demurred, arguing that Carthaginian authority over the Spanish tribes was too fragile and the Roman forces in the area too strong for him to execute the planned movement.[24] Hasdrubal acted by marching into Roman territory in 215 BC, besieged a pro-Roman town and offered battle at Dertosa.[51] In this battle, he used his cavalry superiority to clear the field and to envelop the enemy on both sides with his infantry, a tactic that had been very successfully employed in Italy.[51] However, the Romans broke through the thinned-out line in the centre and defeated both wings separately, inflicting severe losses, but not without taking heavy losses themselves.[51] Hasdrubal now had no chance of reinforcing Hannibal in Italy.[51][23]

War spreads to Sicily and Greece (214–213 BC)

The essence of Hannibal's campaign in Italy was to fight the Romans by using local resources and raising recruits from among the local population. His subordinate Hanno was able to raise troops in Samnium, but the Romans intercepted these new levies in the Battle of Beneventum (214 BC) and eliminated them before they came under the leadership of Hannibal. Hannibal could win allies, but defending them against the Romans was a new and difficult problem, as the Romans could still field multiple armies greatly outnumbering his own forces. Thus Fabius was able to take the Carthaginian ally Arpi in 213 BC.[52]

Africa (213 BC)

While the Romans made little progress in the Iberian theatre, the Scipios were able to negotiate a new front in Africa by allying themselves with Syphax, a powerful Numidian king in North Africa.[51] In 213 BC, he received Roman advisers to train his heavy infantry soldiers that had not yet been able to stand up to their Carthaginian counterparts.[51] With this support, he waged war against the Carthaginian ally Gala.[51] According to Appian, in 213 BC Hasdrubal left Iberia and fought Syphax, though history may have confused him with Hasdrubal Gisco; however, it did tie down Carthaginian resources.[51][53] Hasdrubal Gisco is the son of the Gesco who had served together with Hamilcar Barca, Hannibal's father, in Sicily during the First Punic War and son-in-law of Hanno the Elder who was one of Hannibal's lieutenants in Italy.[51]

Sicily (213–212 BC)

Syracuse, located on the sea routes Hannibal needed to secure supply, and Lilybaeum both remained in Roman hands. Hannibal was aided by the fact that Hiero II, the old tyrant of Syracuse and a staunch Roman ally, had died and his successor Hieronymus was discontented with his position in the Roman alliance. Hannibal dispatched two of his lieutenants, who were of Syracusian origin, to negotiate with Hieronymus. They succeeded in winning Syracuse over, at the price, however, of making the whole of Sicily a Syracusan possession. The Syracusans' ambitions were great, but the army they fielded was no match for the arriving Roman force, leading to the Siege of Syracuse from 213 BC onwards.[54]

The Siege of Syracuse from 213 BC onwards, was marked by Archimedes' ingenuity in inventing war machines that made it impossible for the Romans to make any gains with traditional methods of siege warfare.[55] It was imperative for the Romans to maintain control over Sicily, for otherwise the Carthaginians would be able to reinforce Hannibal in southern Italy with impunity.[24] The Roman commitment would be matched by the Carthaginians.[54]

A Carthaginian army of 25,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 12 elephants under Himilco was sent to relieve the city in 213, landing at and capturing Heraclea Minoa and followed up by taking Agrigentum.[56] Himilco began taking over Roman-garrisoned towns in Sicily. The Roman garrison at Morgantina was betrayed from within, while the Roman garrison commander at nearby Enna heard of Morgantina's treachery and massacred Enna's civilian population. A general revolt against Roman rule in Sicily erupted, with Roman garrisons either being expelled from towns or exterminated by the rebels with Carthaginian support.[56]

Carthaginian zenith (212–211 BC)

Ibera (212–211 BC)

In Iberia, the Carthaginians after 214 were able to stop the wave of defections to Rome.[23] The Scipio brothers captured Saguntum in 212 BC.[51] In 211, they hired 20,000 Celtiberian mercenaries to reinforce their army of 30,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.[51] Observing that the Carthaginian armies were deployed apart from each other, with Hasdrubal Barca and 15,000 troops near Amtorgis, and Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco, both with 10,000 troops, further to the west of Hasdrubal, the Scipio brothers planned to split their forces.[51] Publius Scipio moved 20,000 Roman and allied soldiers to attack Mago Barca near Castulo, while Gnaeus Scipio took one double legion (10,000 troops) and the mercenaries to attack Hasdrubal Barca.[51] This stratagem resulted in two battles, the Battle of Castulo and the Battle of Ilorca, which occurred within a few days of each other, usually combined as the Battle of the Upper Baetis (211 BC).[23][51] Both battles ended in complete defeats for the Romans as Hasdrubal had bribed the Roman mercenaries to desert and return home without a fight.[23][51] The isolated and outnumbered Romans were then killed off by the Carthaginians.[51][23]

As a result of the battles, the Romans were thrown back to their situation of 218. They retreated to their coastal stronghold north of the Ebro, from which the Carthaginians failed to expel them.[51][23] It is notable that the Roman soldiers decided to elect a new leader, since both commanders had been killed, a practice hitherto known only in Carthaginian or Hellenistic armies.[51] Claudius Nero brought over reinforcements in 210 and stabilized the situation.[51]

Italy (212–211 BC)

The climax of Carthaginian expansion was reached when the largest Greek city in Italy, Tarentum, switched sides in 212 BC. The Battle of Tarentum (212 BC) was a carefully planned coup by Hannibal and members of the city's democratic faction. There were two separate successful assaults on the gates of the city. This enabled the Carthaginian army, which had approached unobserved behind a screen of marauding Numidian horsemen, to enter the city by surprise and take all but the citadel where the Romans and their supporting faction were able to rally. The Carthaginians failed to take the citadel, but subsequent fortifications around this Roman stronghold put the city under Carthaginian control. However, the harbour was blocked and warships had to be transported overland to be launched at sea.

The Battle of Capua (212 BC) was a stalemate. The Romans decided to end the siege of Capua. As a result, the Capuan cavalry was reinforced with half of the available Numidian cavalry of 2,000.

In the Battle of Beneventum (212 BC), Hanno the Elder was again defeated, this time by Quintus Fulvius Flaccus, who also captured his camp.[57] In the following Battle of the Silarus, in the same year, the Romans under Marcus Centenius were ambushed and lost all but 1,000 of their 16,000 effectives.[49] Also, in 212 BC, the Battle of Herdonia resulted in another Roman defeat, with only 2,000 Romans out of a force of 18,000 surviving a direct attack by Hannibal's numerically superior forces, combined with an ambush that cut off the Roman line of retreat.[58][59]

During the Roman Siege of Capua (211 BC), Hannibal again tried to regain use of his main harbour as in the previous year, by luring the Romans into a pitched battle. He was unsuccessful, and was also unable to lift the siege by assaulting the besiegers' defences. So he tried a strategem of staging a march towards Rome, hoping in this way to compel the enemy to abandon the siege and rush to defend their home city. However, only part of the besieging force left for Rome and, under continued siege, Capua fell to Rome soon afterwards. Hannibal fought another pitched battle near Rome.[60]

In the spring of 212, Marcellus stormed the walls of Syracuse in a surprise night assault and conquered several districts inside the city.[56] Himilco's army was crippled by the plague and the Romans defeated the Syracusan counter-attacks.[56] Himilco and Hippocrates died soon thereafter of the disease.[56] Bomilcar exited Syracuse's harbor without being troubled by the Romans and re-appeared with 130 quinqueremes and 700 supply ships to lift the siege for good.[56] Poor weather prevented him from arriving before being intercepted by 100 ships under Marcellus.[56] Before battle could be joined at Cape Pacyhnus, Bomilcar decided to flee, ordering the supply ships to return home while the Carthaginian battle fleet sailed to Tarentum.[56] Syracuse fell soon after and Archimedes was killed by a Roman soldier.[56]

In 211 BC, Hannibal sent a force of Numidian cavalry to Sicily, which was led by the skilled Liby-Phoenician officer Mottones, who inflicted heavy losses on Marcellus' army through hit-and-run attacks.[61] Agrigentum's Carthaginian garrison under Hanno engaged Marcellus at the river Himera and were crushed.[62]

Greece (211 BC)

In 211 BC, Rome countered the Macedonian threat with a Greek alliance of the Aetolians, Elis, Sparta, Messenia and Attalus I of Pergamon, as well as two Roman allies, the Illyrians Pleuratus and Scerdilaidas.[63]

The tide turns (210–209 BC)

Spain (210–209 BC)

In 210 BC, Scipio Africanus arrived in Spain with a proconsular imperium and more reinforcements that increased the strength of his army to 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.[64]

In a brilliant assault in 209 BC, Scipio succeeded in capturing lightly-defended Cartago Nova, which was the centre of Carthaginian power in Spain.[65][64] Scipio had the population slaughtered to maximize terror and a vast booty of gold, silver and siege artillery was taken.[8][64] He liberated many Iberian hostages kept by the Carthaginians to ensure the loyalty of the Iberian tribes to their domination.[8][64] These hostages would prove disloyal to the Romans.[64]

Italy (210–209 BC)

Carthage sent more reinforcements to Sicily and Hanno and Mottones went over to the offensive, capturing Macella and re-capturing Morgantina.[62] Marcellus was succeeded by the praetor Marcus Cornelius, who first dealt with indiscipline in the Roman army, after which he checked the Carthaginian progress by taking Morgantina.[62] The hyper-aggressive Roman consul Marcus Valerius Laevinus took charge in 210 BC and immediately marched on Agrigentum to evict Carthage from Sicily.[62] Hanno demoted Mottones and Hanno's son was given the command of the cavalry instead.[62] Mottones betrayed the Carthaginian cause and opened the gates of Agrigentum to the Romans.[62] The Romans massacred the population of the city or sold them to slavery.[62] Hanno and Epicydes fled to Carthage in a merchant ship. Laevinus captured 66 other Sicilian towns, of which 40 surrendered and 26 were taken through force or treachery.[62] He put Sicilian farms back into production and the supply of grain to Rome was resumed in 209 BC.[66]

In Italy, the second Battle of Herdonia (210 BC) was fought to lift the Roman siege of that allied city. Hannibal caught the proconsul Gnaeus Fulvius Centumalus off guard during his siege of Herdonia and destroyed his army in a pitched battle with up to 13,000 Romans dead of 20,000.[60] The defection of the allied city of Salapia in Apulia in 210 BC was achieved by treachery: the inhabitants massacred the Numidian garrison and went over to the Romans.[67]

_03.jpg)

In 210 BC, the Battle of Numistro between Marcellus and Hannibal was inconclusive, but the Romans stayed on his heels until the also inconclusive Battle of Canusium in 209 BC.[68] In the meantime, this battle enabled another Roman army under Fabius to approach Tarentum and take it by treachery in the second Battle of Tarentum (209 BC). Hannibal, at that time, had been able to disengage from Marcellus and was only 8.0 km (5 mi) away when the city, under the command of Carthalo, who was bound to Fabius by an agreement of hospitality, fell.[69]

Roman victory in Italy (208–207 BC)

In the spring of 208 BC, Hasdrubal moved to engage Scipio at the Battle of Baecula.[64] The Carthaginians were defeated, but Scipio was not able to prevent Hasdrubal from continuing his march to Italy in order to reinforce his brother Hannibal.[64][70]

In the spring of 207 BC, Hasdrubal Barca marched across the Alps and invaded Italy with an army of 30,000 men to link up with Hannibal. In southern Italy, Gaius Claudius Nero waged an inconclusive skirmish against Hannibal at the Battle of Grumentum. Nero then tricked Hannibal into believing that the whole Roman army was still in camp, while he marched with a selected corps north and reinforced the Romans engaged against Hasdrubal. The combined Roman force attacked Hasdrubal and destroyed his army at the Battle of the Metaurus on 22 June 207 BC, killing Hasdrubal and scattering the survivors of his army. The outcome of Metaurus confirmed Roman dominance in Italy. Without Hasdrubal's troops, Hannibal was compelled to evacuate allied towns in Italy and withdraw to Bruttium.[71]

Roman victory in Spain (206–205 BC)

In the Battle of Ilipa (206 BC), Scipio with 48,000 men, half of them Italians and the rest Spaniards, defeated a combined army of 54,500 men and 32 elephants under the command of Mago Barca, Hasdrubal Gisco and Masinissa, thus bringing Carthaginian dominance in Spain to an end.[70][64] This catastrophic defeat sealed the fate of the Carthaginian presence in Iberia. It was followed by the Roman capture of Gades in 206 BC after the city had already rebelled against Carthaginian rule.

The Tribal leaders Indibilis and Mandonius (of the Ausetani) thought that, after the expulsion of the Carthaginians, the Romans would leave and they would gain control of Spain again. This didn't happen, however, so they participated with the mutineers at the Sucro camp against the Romans. This mutiny was ultimately squelched by Scipio Africanus.[72]:28.24 In 205 BC, a last attempt was made by Mago to recapture New Carthage when the Roman occupiers were shaken by a mutiny and an Iberian uprising against their new overlords; the attack was repulsed. So, in the same year, Mago left Spain, setting sail from the Balearic islands to Italy with his remaining forces.[8] Carthage in 203 BC succeeded in recruiting at least 4,000 mercenaries from Iberia despite Rome's nominal control.[73]

In 206 BC, there was a quick succession of kings in Eastern Numidia that temporarily ended with the division of the land between Carthage and the Western Numidian king Syphax, a former Roman ally. For this bargain, Syphax was to marry Sophonisba, daughter of Hasdrubal Gisco. Massinissa, who had thus lost his fiancee, went over to the Romans with whom he had already established contact during his military service in Spain.[69]

Roman invasion of Africa (204–203 BC)

At the same time, Scipio Africanus Major was given command of the legions in Sicily and was allowed to levy volunteers for his plan to end the war by an invasion of Africa. The legions in Sicily were mainly the survivors of Cannae, who were not allowed home until the war was finished. Scipio was also one of the survivors but, unlike the ordinary soldiers, had been allowed to return to Rome along with the other surviving tribunes, and had run successfully for public office and had been given command of the troops in Iberia.

After landing in Africa, Scipio besieged and failed to take the city of Utica in the Siege of Utica (204 BC). When a Carthaginian and Numidian relief army under Hasdrubal Barca and Syphax moved to confront Scipio, the Romans mounted a surprise attack on their enemies at the Battle of Utica (203 BC) and defeated them with complete success. Scipio broke out into the Carthaginian hinterland and a second Carthaginian-Numidian army was attacked and destroyed at the Battle of the Great Plains in 203 BC. King Syphax of the Massaesylians (western Numidians), was defeated and taken prisoner after the Battle of Cirta. Masinissa, a Numidian rival of Syphax and, at that time, an ally of the Romans, seized a large part of his kingdom with their help. These setbacks persuaded some in the Carthaginian Senate that it was time to sue for peace. Others pleaded for the recall of Hannibal and Mago, who were still fighting the Romans in Bruttium and Cisalpine Gaul, respectively.

Italy (204–203 BC)

In 205, Mago landed in Genua by sea the remnants of his Spanish army. This was the third Carthaginian force invading Italy. It soon received Gallic and Ligurian reinforcements. Mago's arrival in the north of the Italian peninsula was followed by Hannibal's Battle of Crotona in 204 in the south of the peninsula. Mago marched his reinforced army towards the lands of the Boii and Insubres, Carthage's main Gallic allies and a place of retreat for Hasdrubal's defeated remnants. His move was checked by four Roman legions and allies under Publius Varus and Marcus Cornelius Cethegus at the Battle of Insubria in 203. This hindered the third attempted invasion of Italy early, by preventing Mago from uniting with Hannibal's army in the south.

End of the war (202–201 BC)

In 203 BC, while Scipio was carrying all before him in Africa and the Carthaginian peace party were arranging an armistice, Hannibal was recalled from Italy by the war party at Carthage. After leaving a record of his expedition engraved in Punic and Greek upon bronze tablets in the temple of Juno at Crotone, he sailed back to Africa. These records were later quoted by Polybius. Hannibal's arrival immediately restored the predominance of the war party, who placed him in command of a combined force of Mediterranean mercenaries, African levies and his veterans from Italy. In 202 BC, Hannibal met Scipio in a peace conference. Despite the two generals' mutual admiration, negotiations floundered, according to the Romans due to "Punic faith", meaning bad faith. This Roman expression referred to the alleged breach of protocols which ended the First Punic War by the Carthaginian attack on Saguntum, Hannibal's perceived breaches of what the Romans perceived as military etiquette (i.e., Hannibal's numerous ambuscades), as well as the armistice violated by the Carthaginians in the period before Hannibal's return.

The decisive Battle of Zama soon followed. Unlike most battles of the Second Punic War, the Romans had superiority in cavalry and the Carthaginians had superiority in infantry. Scipio countered an expected Carthaginian elephant charge, which caused some of Hannibal's elephants to turn back into his own ranks, throwing his cavalry into disarray. The Roman cavalry was able to capitalize on this and drive the Carthaginian cavalry from the field. The battle remained closely fought and, at one point, it seemed that Hannibal was on the verge of victory. Scipio's cavalry then returned from chasing the Carthaginian cavalry and attacked Hannibal's rear. This two-pronged attack caused the Carthaginian formation to disintegrate and collapse. After their defeat, Hannibal convinced the Carthaginians to accept peace.[74] Notably, he broke the rules of the assembly by forcibly removing a speaker who supported continued resistance. Afterwards, he was obliged to apologize for his behaviour.

Aftermath

Carthage lost Hispania forever, and Rome firmly established her power there over large areas. Rome imposed a war indemnity[75] of 10,000 silver talents (300 tonnes/660,000 pounds), limited the Carthaginian navy to 10 ships (to ward off pirates), and forbade Carthage from raising an army without Roman permission. The Numidians took the opportunity to capture and plunder Carthaginian territory. Half a century later, when Carthage raised an army to defend itself from these incursions, Rome destroyed her in the Third Punic War (149–146 BC). Rome, on the other hand, by her victory, had taken a key step towards what ultimately became her domination of the Mediterranean world.

The end of the war did not meet with a universal welcome in Rome. When the Senate decided upon a peace treaty with Carthage, Quintus Caecilius Metellus, a former consul, said he did not look upon the termination of the war as a blessing to Rome, since he feared that the Roman people would now sink back again into its former slumbers, from which it had been roused by the presence of Hannibal.[76] Others, most notably Cato the Elder, feared that if Carthage was not completely destroyed it would soon regain its power and pose new threats to Rome; he pressed for harsher peace conditions. Even after the peace, Cato insisted on the destruction of Carthage, ending all his speeches with "Carthage must be destroyed", even if they had nothing to do with Carthage.[77]

Archaeology has discovered that the famous circular military harbour at Carthage, the Cothon, received a significant buildup during or after this war. Though shielded from external sight, it could house and quickly deploy about 200 triremes. This appears a surprising development as, after the war, one of the terms of surrender restricted the Carthaginian fleet to only ten triremes. One possible explanation: as has been pointed out for other Phoenician cities, privateers with warships played a significant role besides trade, even when the Roman Empire was fully established and officially controlled all coasts. In this case it is not clear whether the treaty included private warships. The only reference to Carthaginian privateers comes from the First Punic War: one such privateer, Hanno the Rhodian, owned a quinquereme (faster than the serial production models that the Romans had copied), manned with about 500 men and then among the heaviest warships in use. Later pirates in Roman waters are all reported with much smaller vessels, which could outrun naval vessels, but operated with lower personnel costs. Thus piracy was probably highly developed in Carthage and the state did not have a monopoly of military forces. Pirates probably played an important role in capturing slaves, one of the most profitable trade-goods, but merchant ships with tradeable goods and a crew were also their targets. No surviving source reports the fate of Carthaginian privateers in the periods between and after the Punic Wars.

Hannibal became a businessman for several years and later enjoyed a leadership role in Carthage. However, the Carthaginian nobility, upset by his policy of democratisation and his struggle against corruption, persuaded the Romans to force him into exile in Asia Minor, where he again led armies against the Romans and their allies on the battlefield. He eventually committed suicide (c. 182 BC) to avoid capture.

Constant low-level warfare persisted between Carthage and Numidia, but, by the time of the Third Punic War (149–146 BC), Carthage had lost most of its African territories and the Numidians traded independently with the Greeks.

Intelligence

In this conflict, intelligence played an important role on both sides. Hannibal mastered an intelligence service that enabled him to achieve outstanding victories.[78] Likewise, Scipio Africanus Major's victories depended on information. In 217 BC, a Carthaginian resident spy in Rome—probably a Roman citizen—was caught and had his hands cut off as a punishment.[5]:22.33.1[79]

Opinions on the war

Livy portrayed the Punic War as

"the most memorable of all wars that were ever waged: the war which the Carthaginians, under the conduct of Hannibal, maintained with the Roman people. For never did any states and nations more efficient in their resources engage in contest; nor had they themselves at any other period so great a degree of power and energy. They brought into action too no arts of war unknown to each other, but those which had been tried in the first Punic war; and so various was the fortune of the conflict, and so doubtful the victory, that they who conquered were more exposed to danger. The hatred with which they fought also was almost greater than their resources."[5]

:21.1

In popular culture

- G. A. Henty's 1887 historical novel The Young Carthaginian tells the story of Hannibal and the Second Punic War from the perspective of the fictional character Malchus, a cousin of Hannibal.

- Hannibal's exploits, as well as those of Archimedes and the siege of Syracuse, appear dramatically reenacted in the classic Italian silent film Cabiria (1914).

- The BBC TV Series On Hannibal's Trail screened in 2009.

- The Scipio Africanus trilogy is a historical fiction by Santiago Posteguillo that describes in detail the history of the multiple conflicts between Hannibal and Scipio Africanus

See also

- Socii

- Equestrian order

- Carthaginian peace

- Hannibal

- Scipio Africanus Major

- War elephant

- Barcid

- List of battles of the Second Punic War

- Polybius wrote a detailed history, showing contemporary insight into the political process of this time.

- Silius Italicus, who dramatised the war in his poem Punica

- Petrarch, who wrote an epic on the war entitled Africa

- Plutarch's Lives for lives of two of the Roman generals, Fabius Maximus and Gaius Flaminius. Plutarch's life of Scipio Africanus is lost.

References

Notes

- The motives are obscure. Livy and Polybius present a range of speculations: the oath sworn as a child by Hannibal to his father never to make peace with Rome, intervention on behalf of the pro-Carthaginian party at Saguntum, provocation of Rome as an excuse for invasion, enforcement of the Ebro boundary, greed, etc.

- Livy, Book XXI, Chapter 15, points out that "some writers" (Polybius, Book III, Chapter 34) have Hannibal wintering at New Carthage before setting out for Italy in "early spring" (March 15; see under Roman Calendar). The fall of Saguntum would have been over and the consuls mentioned could not have received their envoys. Livy keeps the consuls and moves the fall of Saguntum to after March, but he does not reconcile all his information. Polybius' account with the winter encampment appears later in the text.

- For another point of view: Polybius. "III.20". Histories. ISBN 88-317-9986-X.

The Romans, when the news of the fall of Saguntum reached them, did not assuredly hold a debate on the question or war, as some allege.... For how could the Romans, who a year ago had announced to the Carthaginians that their entering the territory of Saguntum would be regarded as a casus belli... now assemble to debate whether they should go to war or not?

Even immediately after the events, the Romans did not have a clear and consistent understanding of what happened.

Citations

- Beck 2011, p. 227.

- Matthew White, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things (Norton, 2012)

- Bagnall 1990, p. vii.

- Hoyos 2015, pp. 101, 299.

- Livy. The History of Rome by Titus Livius: Books Nine to Twenty-Six, trans. D. Spillan and Cyrus Edmonds. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1868.

- Beck 2011, p. 235.

- Barceló 2011, p. 360.

- Barceló 2011, p. 362.

- Livy. . History of Rome. ISBN 0-520-24139-8.

- Livy, Book XXI, Chapters 1–14.

- Livy XXI, 16.

- Rev. Canon Roberts translation of Livy XXI, 17.

- Livy XXI.18.

- Barceló 2011, pp. 362–363.

- Barceló 2011, p. 364.

- Hoyos 2010, p. 206.

- Barceló 2011, pp. 365–367.

- Hoyos 2015, p. 129.

- Barceló 2011, p. 371.

- Mahaney, W.C., 2008, Hannibal's Odyssey: Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia. Gorgias Press, Piscataway, N.J., 221 pp. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.

- Lazenby 1978, p. 41.

- Fronda 2011, p. 252.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 291.

- Edwell 2011, p. 321.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 151.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 283.

- Delbrück, p. 362

- Jr, Hans Delbrück; translated from the German by Walter J. Renfroe (1990). History of the art of war. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press/ Bison Book. ISBN 978-0-8032-9199-7.

- Fronda 2011, p. 243.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 284.

- Fronda 2011, pp. 243–244.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 285.

- Liddell Hart, B. H., Strategy, New York City, Penguin Group, 1967

- Fronda 2011, p. 244.

- Fronda 2011, p. 245.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 286.

- Polybius, 3.114

- Dodge 1891, p. 242.

- Polybius, 3.95

- Dodge 1891, p. 403.

- Healy, Mark, Cannae: Hannibal Smashes Rome's Army, Steerling Heights, Missouri, Osprey

- Fronda 2011, p. 249.

- Hoyos 122f

- Hoyos 2015, p. 127.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 313.

- Hoyos 132

- Hoyos 2015, p. 132.

- Hoyos 2011, p. 75.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 301.

- Barceló 2011, p. 365.

- Edwell 2011, p. 322.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 312.

- Hoyos 139

- Edwell 2011, p. 327.

- Edwell 2011, p. 328.

- Edwell 2011, p. 329.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 316.

- Hoyos 2011, p. 85.

- Fronda 2011, p. 253.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 300.

- Edwell 2011, pp. 329–330.

- Edwell 2011, p. 330.

- Livy, XXVI.40. According to F. W. Walbank, p. 84, note 2, "Livy accidentally omits Messenia and erroneously describes Pleuratus as king of Thrace."

- Edwell 2011, p. 323.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 292.

- Rawlings 2011, p. 311.

- Lomas 2011, p. 350.

- Rawlings 2011, pp. 301–302.

- Barceló 2011, p. 372.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 293.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 290.

- Livy. The History of Rome by Titus Livius: Books Twenty-Seven to Thirty-Six, trans. Cyrus Edmonds. London: 1850.

- Edwell 2011, p. 333.

- Zimmermann 2011, p. 295.

- "Punic Wars".

- Valerius Maximus vii. 2. §3.

- Plutarch, Life of Cato

- Zlattner 1997

- Austin&Rankov 1995, p. 93

Primary sources

Secondary sources

- Ameling, Walter (1993). Karthago: Studien zu Militär, Staat und Gesellschaft (in German). Munich. ISBN 3-406-37490-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Austin, N.J.E., and N.B. Rankov. 1995. Exploratio: Military and Political Intelligence In the Roman World From the Second Punic War to the Battle of Adrianople. London: Routledge.

- Bagnall, Nigel (1990). The Punic Wars. Thomas Dunne Books; First Edition edition. ISBN 0-312-34214-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barceló, Pedro A. (1988). Karthago und die iberische Halbinsel vor den Barkiden: Studien zur karthagischen Präsenz im westlichen Mittelmeerraum von der Gründung von Ebusus bis zum Übergang Hamilkars nach Hispanien (in German). Bonn. ISBN 3-7749-2354-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barceló, Pedro (2011). "Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beck, Hans (2011). "The Reasons for the War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (1891). Hannibal. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81362-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwell, Peter (2011). "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fronda, Michael P. (2011). "Hannibal: Tactics, Strategy, and Geostrategy". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoyos, Dexter (2010). The Carthaginians. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-85132-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2000). The Punic Wars. London: Cassell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage. ISBN 978-03043-6642-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lancel, Serge (1995). Hannibal (in French).

- Lazenby, John Francis (1978). Hannibal's War. ISBN 978-0-8061-3004-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lomas, Kathryn (2011). "Rome, Latins, and Italians in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mahaney, W.C, 2008. "Hannibal's Odyssey, Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia," Gorgias Press, Piscataway, NJ 221 pp.

- Palmer, Robert E.A. (1997). Rome and Carthage at Peace. Stuttgart.

- Rawlings, Louis (2011). "The War in Italy, 218–203". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2011). "Roman Strategy and Aims in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zlattner, Max (1997). Hannibals Geheimdienst im Zweiten Punischen Krieg (in German). Konstanz. ISBN 3-87940-546-8.

Further reading

- Bellón, Juan Pedro, Carmen Rueda, Miguel Ángel Lechuga, and María Isabel Moreno. 2016. "An Archaeological Analysis of a Battlefield of the Second Punic War: the Camps of the Battle of Baecula." Journal of Roman Archaeology 29: 73–104. doi:10.1017/S1047759400072056.

- Daly, Gregory. 2002. Cannae: The experience of battle in the Second Punic War. New York: Routledge.

- Fronda, Michael P. 2010. Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoyos, Dexter. 1998. Unplanned wars: The origins of the First and Second Punic Wars. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ————. 2003. Hannibal’s dynasty: Power and politics in the western Mediterranean 247–183 BC. New York: Routledge.

- Rich, John. 1996. "The origins of the Second Punic War." In The Second Punic War: A reappraisal. Edited by Tim Cornell, Boris Rankov, and Philip Sabin, 27–54. London: Univ. of London, Institute of Classical Studies.