Serboi

The Serboi (Ancient Greek: Σέρβοι, romanized: Sérboi) was a tribe mentioned in Greco-Roman geography as living in the North Caucasus, believed by scholars to have been Sarmatian. In 10th century, Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos mentions in his book De Ceremoniis two tribes named Krevatades (Krevatas) and Sarban (Sarbani) located in the Caucasus near Alania. There were most likely the original Sarmatian tribes. Today some researches identified as Croats and Serbians.

Greco-Roman Ptolemy (100–170) mentioned in his Geography (ca. 150) the Serboi as inhabiting, along with other tribes, the land between the northeastern foothills of the Caucasus and the Volga.[1] Moszyński derived the name from Indo-European *ser-, *serv-, meaning "guard, protect" (cognate of Latin servus), and originally, it may have meant "guardians of animals", that is "shepherds".[2] Similar toponyms were mentioned earlier farther away.[a]

The Sarmatians were eventually decisively assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) and absorbed by the Proto-Slavic population of Eastern Europe around the Early Medieval Age.[3] Scholars have connected the ethnonym with those of the Slavic peoples of Serbs and Croats in Europe.[b] There is a theory that "Horoati" and their kin Serboi fled a Hunnic invasion into southern Poland and southeast Germany[c] where they were assimilated by Slavs, and by the time of the 7th-century Slavic migration to the Balkans were completely Slavicized.[2] Others believe that the tribe may in fact have been early Slavic, as noted by Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (1921–1994),[4] and others.[5] While some Serbian historians treat them as a Sarmatian tribe that was part of the Proto-Serb ethnogenesis,[6] some alternate historians treat them as a historical Serb tribe, pushing the Serbs' history further into antiquity.[7]

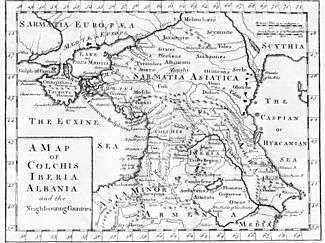

The tribe was included on maps of the antique Sarmatia Asiatica as Serbi, Sirbi, in the Early modern period.

See also

- Origin hypotheses of the Serbs

- Sabirs

- White Serbs

- Serbs

- Sorbs

- Early Slavs

Annotations

- ^ Roman author Pliny the Elder (23–79) mentioned the "Serbonian Lake" near Palestine in his Natural History.[8]

- ^ Proponents of the Iranian theory of Croat origin view that the Sarmatian *serv- may have turned into *harv- which is very similar to "Hrvat, Croat"; P. S. Sakać found Harahvaiti, Harahvatis, Horohoati denoting a province and people close to modern Afghanistan in Persian descriptions dating to Darius' time.[9] However, Croatian scholar Radoslav Katičić refutes it as although the suggestive similarity, it is etymologically incorrect.[10] Fine Jr. believes there are considerable evidence suggesting a non-Slavic, probably Iranian, origin of the 7th-century Serbs and Croats.[11] In the 10th-century De Ceremoniis of Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitos, the Krevatades and Sarban are mentioned located in the Caucasus near river Terek, and some scholars view that these were the ancestors of Croats and Serbs.[12][13] According to Polish scholar Tadeusz Sulimirski (1898–1983), the Serbs who settled in the Balkans were Slavs who came from the north and were ruled by already slavicized Alans.[14] Lubor Niederle (1865–1944) connected the Serbs with both the Serboi and the later Sporoi.[15]

- ^ Where the White Croats lived in the Middle Ages, and where today, there is still a Slavic people called "Sorbs" that inhabit that region.[2]

References

- Bell-Fialkoff 2000, p. 136, Gimbutas 1971, p. 60

- Bell-Fialkoff 2000, p. 136.

- Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, p. 39.

- Gimbutas 1971, p. 60.

- Petković, Živko D. (1996) [1926]. Prve pojave srpskog imena. Beograd. p. 9.

- Milanović, Miodrag (2008). Srpski stari vek. Beograd. p. 81., Novaković, Relja (1992). Još o poreklu Srba. Beograd. p. 46.

- Petrović, Aleksandar M. (2004). Праисторија Срба: разматрање грађе за стару повесницу. Пешић и синови.

- Pliny the Elder (1989). Pliny: Natural History. Harvard University Press. p. 271.

- Bell-Fialkoff 2000, p. 136; P. S. Sakac, Iranische Herkunft des kroatischen Volksnamens, Orient. Christ. Per. XV, 1949, 313-340

- Katičić, Radoslav (1999), Na kroatističkim raskrižjima [At Croatist intersections] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji, p. 12, ISBN 953-6682-06-0

- John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1949). Gy. Moravcsik (ed.). De administrando imperio. Translated by R.J.H. Jenkins. Pázmány Péter Tudományegyetemi Görög Filoĺ́ogiai Intézet. p. 115.

- Dvornik 1959, p. 28.

- Novaković 1992, p. 48.

- Niederle 1923, p. 34.

Sources

- Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew, ed. (2000). "The Slavs". The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentary Civilization vs. 'Barbarian' and Nomad. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-1-349-61837-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians 600 BC–AD 450. Men-At-Arms (373). Bloomsbury USA; Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-485-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dvornik, Francis (1959). The Slavs: their early history and civilization. American Academy of Arts and Sciences.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gimbutas, Marija (1971). The Slavs. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 60.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Niederle, Lubor (1923). Manuel de l'antiquité slave ... É. Champion.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)