Origin hypotheses of the Serbs

The Serbs trace their history to the 6th and 7th-century southwards migration of Slavs. The Serbs, as the other South Slavs, absorbed Paleo-Balkan peoples and established various states throughout the Middle Ages; Serbian historiography agrees on that the beginning of Serbian history started with the forming of Serbian statehood in the Early Middle Ages.

In the 19th century, various scholars provided several theories about the origin of the Serb ethnonym. Some researchers claimed that the ethnonym, and thereby ethnic origin, dated to ancient history. The theories are based on new findings in genetics and the presumed connection to various Roman-era ethnonyms (tribes) and toponyms.

Early historical records of the Serb name

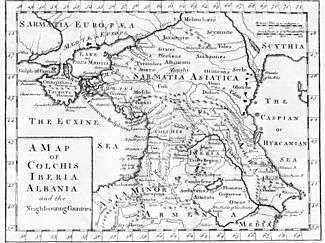

Various authors mentioned names of Serbs (Serbian: Srbi / Срби) and Sorbs (Upper Sorbian: Serbja; Lower Sorbian: Serby) in different variants: Surbii, Suurbi, Serbloi, Zeriuani, Sorabi, Surben, Sarbi, Serbii, Serboi, Zirbi, Surbi, Sorben,[1] etc. These authors used these names to refer to Serbs and Sorbs in areas where their historical (or current) presence was/is not disputed (notably in the Balkans and Lusatia), but there are also sources that mention the same or similar names in other parts of the World (most notably in the Asiatic Sarmatia in the Caucasus). Attempts of various researchers to connect these names with modern Serbs produced various theories about the origin of the Serb people.

- Early historical mentions of an alleged "Serb" ethnonym in the Caucasus

- Pliny the Younger in his work Plinii Caecilii Secundi Historia naturalis from the first century AD (69-75) mentioned people named Serboi, who lived near the Cimmerians, presumably on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.[2]

- In the 2nd century (around 175 AD), the Egyptian Greek scientist Claudius Ptolemy mentioned in his Geography people named Serboi or Sirboi, who presumably lived behind the Caucasus, in the hinterland of the Caspian Sea.[2]

- Early historical mentions of other Serb-sounding names that some researchers are trying to connect with the Serb people

- In the same book where he mentioned people named Serboi, Claudius Ptolemy also mentioned city named Serbinum in Pannonia.[2]

- Ancient geographer Strabo mentioned that river Xanthos in Lycia was formerly named Sirbis.[3]

- Herodotus mentions lake named Serbonis in Egypt. This lake was also mentioned as Sirbonis by Strabo.[4]

- In the 10th century, Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (912-959) mentioned in his book De Ceremoniis, apart from the Slavic Croats and Serbs, there were two tribes named Krevatades (Krevatas) and Sarban (Sarbani), which some researches identified as Croats and Serbs. These tribes were located in the Caucasus near the river Terek, between Alania and Tsanaria.[5][6][7][8] The Sarban tribe in the Caucasus in the 10th century was also recorded by an Arab geographer.[9]

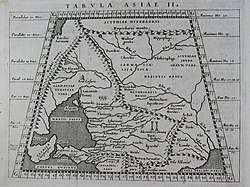

People with name Sirbi near the estuary of the river Volga, on Ptolemaic map from 1552.

People with name Sirbi near the estuary of the river Volga, on Ptolemaic map from 1552. People with name Sirbi near the estuary of the river Volga, on Ptolemaic map from 1598.

People with name Sirbi near the estuary of the river Volga, on Ptolemaic map from 1598.- People with name Serbi (Серби) near the estuary of the river Volga, according to the map from the book of Jovan Rajić, printed in Vienna in 1794.

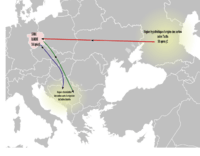

Migration of White Serbs to the Balkans

.png)

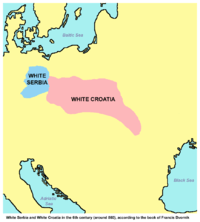

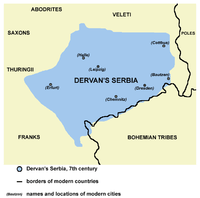

According to De Administrando Imperio (DAI, written by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII (912-959), the Serbs originated from the "White Serbs" who lived on the "other side of Turkey" (name used for Hungary), in the area that they called "Boiki". White Serbia bordered to the Franks and White Croatia. DAI claims that after two brothers inherited the rule from their father, one of them took half of the people and migrated to the Byzantine Empire (i.e. to the Balkans), which was governed by Emperor Heraclius (610-641).[10][11][12] According to German historian L. A. Gebhardi, the two brothers were sons of Dervan, the dux (duke) of the Surbi (Sorbs).[13]

In the Balkans, Serbs settled first an area near Thessaloniki and then area around rivers Tara, Ibar, Drina and Lim (in the present-day border region of Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also Dalmatia), and joined with surrounding South Slavic tribes that came to the Balkans earlier (in the 6th century) and the Paleo-Balkan people. Over time, the South Slavic and mostly Illyrian tribes of this territory mixed with the Serbs and also adopted Serb name as their own.[14][15]

Another part of the White Serbs did not migrate southwards, but remained in the Elbe region. Descendants of these White Serbs are the present day Lusatian Serbs (Sorbs), who still live in the Lusatia (Lužica, Lausitz) region of eastern Germany.

There are also opinions that data from "De administrando imperio" that describes Serb migration to the Balkans is not correct and that Serbs came to the Balkans from Eastern Slavic lands, together with other South Slavs.[16][17]

The Emperor Constantine III (641) transferred a part of the Slavs from the Balkans (Vardar region) to Asia Minor. There these migrants founded the city of Gordoservon, the name of which gives grounds for supposing that among its founders there were Serbs.[18] The city was also known under names Gordoserbon and Servochoria.

Theories

Iranian theory

Theory about Iranian origin of the Serb ethnonym assumes that ancient Serbi / Serboi from north Caucasus (Asiatic Sarmatia) were a Sarmatian (Alanian) tribe.[19] The theory subsequently assumes that Alanian Serbi were subdued by the Huns in the 4th century and that they, as part of the Hunnic army, migrated to the western edge of the Hunnic Empire (in the area of Central Europe near the river Elbe, later designated as White Serbia in what is now Saxony (eastern Germany) and western Poland). After the Hunnic leader Attila died (in 453), Alanian Serbi presumably became independent and ruled in the east of the river Saale (in modern-day Germany) over the local Slavic population.[19][20] Over time, they, it is argued, intermarried with the local Slavic population of the region,[19][20] adopted Slavic language, and transferred their name to the Slavs.[21] According to Tadeuš Sulimirski, similar event could occur in the Balkans or Serbs who settled in the Balkans were Slavs who came from the north and who were ruled by already slavicized Alans.[20]

Deformed human skulls that are connected to the Alans are also discovered in the area that was later designated as "White Serbia".[21] According to Indo-European interpretation, different sides of the World are designated with different colors, thus, white color is designation for the west, black color for the north, blue or green color for the east and red color for the south. According to that view, White Serbia and White Croatia were designated as western Serbia and western Croatia, and were situated in the west from some hypothetical lands that had same names and that presumably existed in the east.[22]

It is possible that the Alanian Serbi in Sarmatia, similarly like other Sarmatian/Iranian peoples on the northern Caucasus, originally spoke an Indo-European Iranian language similar to present-day Ossetian. The Ossetian language is a member of Eastern Iranian branch of Iranian languages, along with Pashtun, Yaghnobi and languages of the Pamir. One of the Pashtun tribal groups in Afghanistan and Pakistan is known as Sarbans (Sarbani) and Pashtuns are believed to be of Scythian descent while their language is classified as East Scythian (Sarmatian language is also grouped within Scythian branch).

In Polish history, the Polish nobility claimed to be direct descendants of the historic Sarmatian people (see: Sarmatism) and this might be connected with historical White Serbia and White Croatia, which included parts of present-day Poland.

Autochthonic theory

This theory assumes that Serbs are an autochthonic people in the Balkans and Podunavlje, where they presumably lived before historical Slavic and Serb migration to the Balkans in the 6th-7th centuries.[23] Proponents of this theory (for example Jovan I. Deretić, Olga Luković Pjanović, Miloš Milojević) claimed that Serbs either came to the Balkans long before the 7th century or Serb 7th century migration to the Balkans was only partial and Serbs who, according to "De administrando imperio", came from the north founded in the Balkans other Serbs that already lived there.[23] It is suggested that ancient city of Serbinum in Pannonia was named after these hypothetical autochthonic Serbs. In mainstream historiography this is considered to be a fringe theory, and the methods used by its proponents are often pseudoscientific.[24]

Proto-Slavic theory

- Sporoi (Greek: Σπόροι) was according to Eastern Roman scholar Procopius (500–560) the old name of the Antae and Sclaveni, two Early Slavic branches. Procopius stated that the Sclavenes and Antes spoke the same language, but did not trace their common origin back to the Venethi but to a people he called "Sporoi".[25] He derived the name to Greek σπείρω ("I scatter grain"), because "they populated the land with scattered settlements".[26] According to Bohemian historian Josef Dobrovský (1753–1829) and Slovak historian Pavel Jozef Šafárik (1795–1861) it was a corruption of Srbi (Serbs).[27] Šafárik deemed that it was the oldest generic name of the Slavs.[28]

- In the mid-9th century the so-called Bavarian Geographer wrote that people named Zeriuani had so large kingdom that all Slavic peoples originated from there (or from them).[29][30] According to one of interpretations, Zeriuani are identified with Serbs, and there are opinions that "Serbs" was an old name of all Slavic peoples.[31] However, according to other opinions, Zeriuani might be a name used for Severians or Sarmatians instead for Serbs.[32]

References

- Petković 1926, p. 9.

- Aleksandar M. Petrović, Arheografija naroda jugoistočne Evrope, Beograd, 2006, page 19.

- Aleksandar M. Petrović, Arheografija naroda jugoistočne Evrope, Beograd, 2006, page 20.

- Petković 1926, pp. 18–19.

- De administrando imperio, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (Emperor of the East), Gyula Moravcsik, Pázmány Péter Tudományegyetemi Görög Filológiai Intézet, 1949, page 115.

- Parameśa Caudhurī, India in Kurdistan, Qwality Book Company, 2005, page 79.

- The Slavs: their early history and civilization, Francis Dvornik, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1959, page 28.

- Constantini Porphyrogenneti... libri duo De ceremoniis aulæ Byzantinæ. Prodeunt nunc primum Græce, cum Latina interpretatione et commentariis. Curarunt Io. Henricus Leichius et Io. Iacobus Reiskius..., VII Constantin, Gleditschius, 1754, page 397.

- The early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century, John Van Antwerp Fine, University of Michigan Press, 1991, page 56.

- Sava S. Vujić - Bogdan M. Basarić, Severni Srbi (ne)zaboravljeni narod, Beograd, 1998, pages 38-39.

- Petrović 1997, pp. 90-91.

- Vladimir Ćorović, Ilustrovana istorija Srba, knjiga prva, Beograd, 2005, page 61.

- Sava S. Vujić - Bogdan M. Basarić, Severni Srbi (ne)zaboravljeni narod, Beograd, 1998, page 40.

- Sava S. Vujić - Bogdan M. Basarić, Severni Srbi (ne)zaboravljeni narod, Beograd, 1998, page 36.

- Sima M. Ćirković, SRBI MEĐU EUROPSKIM NARODIMA,(Serbs) 2008. http://www.mo-vrebac-pavlovac.hr/attachments/article/451/Sima%20%C4%86irkovi%C4%87%20SRBI%20ME%C4%90U%20EVROPSKIM%20NARODIMA.pdf #page=26-27

- Novaković 1992, p. 57.

- Nikola Jeremić, Srpska zemlja Bojka, Zemun, 1993, page 33.

- The Macedonian question: the struggle for southern Serbia, Đoko M. Slijepčević, American Institute for Balkan Affairs, 1958, page 50.

- Miodrag Milanović, Srpski stari vek, Beograd, 2008, page 81.

- Novaković 1992, p. 46.

- Novaković 1992, p. 48.

- Relja Novaković, Srbi, Zemun, 1993, page 61.

- Petrović 1997, pp. 9–10.

- Petrović 1997, p. 8.

- Paul M. Barford (January 2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8014-3977-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Михайло Грушевський; Andrzej Poppe; Marta Skorupsky; Uliana M. Pasicznyk; Frank E. Sysyn (1997). History of Ukraine-Rus': From prehistory to the eleventh century. Kiyc Cius. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-895571-19-6.

- J. B. Bury 2013, p. 295

- Royal anthropological institute (1879). The Journal of the Anthropological institute. 8. p. 66.

- Petrović 1997, p. 90.

- Quaestiones medii aevi, Томови 1-4, Uniwersytet Warszawski. Instytut Historyczny, Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne. Commission d'histoire médiévale, Éditions de l'Université de Varsovie, 1977, page 31.

- Lazo M. Kostić, O srpskom imenu, Srbinje - Novi Sad, 2000, pages 38-39.

- Prosvjeta, Том 16, Društvo hrvatskih književnika., 1908, page 216.

Sources

- Petrović, Aleksandar M. (1997). Kratka arheografija Srba: (Srbi prema spisima drevnih povesnica). Nevkoš.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petković, Živko D. (1926). Prve pojave srpskog imena. Štampa Tucović.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Novaković, Relja (1992). Još o poreklu Srba. Miroslav.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)