Seisia, Queensland

Seisia /ˈseɪʃə/ is a coastal town and a locality in the Northern Peninsula Area Region, Queensland, Australia.[2][3] In the 2016 census, Seisia had a population of 260 people.[1]

| Seisia Queensland | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sunset at Seisia | |||||||||||||||

Seisia | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 10.85°S 142.3680°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 260 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 113/km2 (293/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 4876 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 2.3 km2 (0.9 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

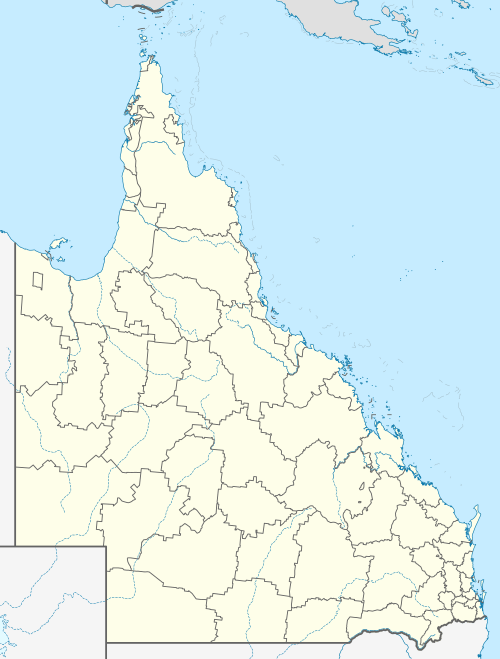

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Northern Peninsula Area Region | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Cook | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Leichhardt | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Geography

Seisia is the area north of New Mapoon and west of Bamaga on Cape York Peninsula.

Seisia Island Community lies within a small DOGIT area granted in 1986 by the Queensland Government at Red Island Point The community has a permanent population of about 100 people and is situated at the most northerly deep-water port on Cape York Peninsula

Attractions

Seisia is popular as a destination for anglers and a number of fishing charter operators use Seisia as their base. A campground at Seisia is used by about 50 per cent of camping travelers to Northern Cape York Peninsula.

The majority of tourist services in the Northern Peninsula Area (NPA) are provided under lease arrangements with the Seisia Island Council. Seisia is becoming increasingly well known as the "Gateway to the Torres Strait" and as a base on the mainland to educate and inform visitors about Torres Strait Islander culture. Tours linking Seisia with a number of Torres Strait islands (including the market days on Saibai) have commenced, capitalizing on opportunities to educate visitors as to the historical links between Seisia and the Torres Strait. A number of recreational fishing guides can be contacted through the Seisia Village campground.

History

European contact

Seisia, formerly known as Red Island Point, is also known as Ithangee in its Aboriginal language. Ithunchi was originally used as a traditional camping site before European contact.[4] The Oiyamkwi clan of the Ankamuti was indigenous to the island.[5]

In 1864, a government settlement was established at Somerset at the tip of Cape York. The introduction of diseases, exclusion from traditional hunting grounds and the brutality of Native Police under the direction of Somerset’s Police Magistrates, decimated the Aboriginal people of the NPA.[6] By 1915, surviving remnants of the Aboriginal population had regrouped at Red Island Point and Cowal Creek. Yadhaigana, Wuthathi, Unduyamo and Gudang people from the north and east had established themselves as a single group at Red Island Point. Other Yadhaigana people and Wuthathi had formed a group at Injinoo (known then as Small River).[7] The two communities approached the government for land to establish gardens, leading to the creation of an Aboriginal reserve at Cowal Creek in 1915.[8] An Anglican mission and school took over the administration of the reserve in 1923.[9]

In 1942 during World War II, US Army engineers established a military airstrip inland from Red Island Point. The airstrip was known as the Jacky Jacky or Higgins airstrip. A number of RAAF bomber, fighter and transport squadrons operated from the airstrip. It is still used today as the airport for the Northern Peninsula Area. A radar station was also established at Muttee Heads in 1943 with local Aboriginal people assisting in its construction and operation. New jetties and wharves were built by Army engineers at Muttee Heads and Red Island Point.[10]

At the end of World War Two, the Queensland Government introduced measures aimed at compensating Torres Strait Islanders for their contribution to the war effort. These were also intended to populate the north as a defence mechanism against foreign invasion. Around 1945, the Director of Native Affairs, Cornelius O’Leary, inspected the North Peninsula Area with a local stockman, Dick Holland, to identify suitable locations for a new settlement. In his opening address to the 1947 Island Councillors’ Conference held at Badu, O’Leary spoke of the government’s "wish for the expansion of the Torres Strait Race as a healthy industrial unit in North Queensland".[11][12]

During the war years, enlisted Torres Strait Islander men from Saibai, Dauan and Boigu also discussed the possibility of developing an Islander community on the Australian mainland. These discussions continued after the war at Saibai, with the involvement of Island elders and leaders. Saibai elder Bamaga Ginau supported the proposal. He held strong concerns regarding the inadequate supplies of freshwater and firewood on Saibai and the damaging effects of poor drainage, disease and king tides. In 1947, a series of king tides during the wet season caused "serious and in some cases irreparable damage to properties and gardens" on Saibai. Bamaga Ginau called a meeting regarding his concerns for the future of Saibai. After much discussion, a number of Saibai families made the decision to leave the Island and move to the mainland.[13][14]

The first party of Saibai families left the island in May 1947 on the pearl luggers Millard and Macoy. They arrived at Muttee Heads on the NPA on 1 June 1947. A second party, which included Bamaga Ginau and his family, arrived on 1 July 1947. The new arrivals selected a temporary site at Muttee Heads for their new settlement.[15] The Queensland Government, in July 1948, gazetted an area of 44,500 acres extending from Red Island Point to Kennedy Inlet, south to the boundary of the Cowal Creek mission settlement, as a reserve for the "use of the Torres Strait Islanders".[16] In 1948, Mugai Elu and Tumena Sagaukaz left Saibai with their families and moved to Red Island Point. The families lived in old army huts donated to them by Stan Holland. More families from Saibai settled at Red Island Point in 1950 and 1951. Representatives from the small community approached the Department of Native Affairs to build new housing at Red Island Point in 1955.[17]

On 14 October 1972, the Anglican Church of St. Francis of Assisi was officially dedicated at Red Island Point. Five years later the name Seisia was adopted by the community at Red Island Point. The name Seisia was taken from the first letters of the names of Mugai Elu’s fathers and brothers – Sunai, Elu, Ibuai, Sagaukaz, Isua and Aken.[17][18]

Local government and Deed of Grant in Trust community

On 30 March 1985, the Seisia community elected 3 councillors to constitute an autonomous Seisia Island Council established under the Community Services (Torres Strait) Act 1984. The Act conferred local government type powers and responsibilities upon Torres Strait Islander councils for the first time. Umagico, Bamaga, New Mapoon and Cowal Creek also elected council representatives at this time.

On 29 October 1987, the council area, previously an Aboriginal reserve held by the Queensland Government, was transferred to the trusteeship of the council under a Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT).[19]

At the 2006 census, Seisia had a population of 165.[20]

In 2007, the Local Government Reform Commission recommended that the 3 NPA Aboriginal Shire Councils and the 2 NPA Torres Strait Islander Councils be abolished and a Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council be established in their place. The first Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council (NPARC) was elected on 15 March 2008 in elections conducted under the Local Government Act 1993.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Seisia (SSC)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Seisia - town in Northern Peninsula Area Region (entry 30370)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Seisia - locality in Northern Peninsula Area Region (entry 46106)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- N Sharp, Footprints Along the Cape York Sandbeaches (Australian Studies Press, Canberra; 1992) 12.

- Tindale, Norman (1974). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia (PDF). Australian National University Press. p. 196.

- N Sharp, Footprints Along the Cape York Sandbeaches (Australian Studies Press, Canberra; 1992) 35-40, 55-58.

- N Sharp, Footprints Along the Cape York Sandbeaches (Australian Studies Press, Canberra; 1992) 15, 85-87.

- Queensland State Archives, Home Secretary’s Office, HOM/J129, 1914/9001, Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals on the Annual Inspection of Northern Institutions, 1915; Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 23 October 1915, 1374.

- Queensland, Report on the Operations of Certain Sub-Departments of the Home Secretary’s Department - Aboriginals Department - Information contained in Report for the Year ended 31st December, 1920 (1921) 9; Queensland, Report on the Operations of Certain Sub-Departments of the Home Secretary’s Department - Aboriginals Department. - Information contained in Report for the Year ended 31st December, 1918 (1919)10; Queensland Parliamentary Papers, 1926, 11.

- R Marks, Queensland Airfields, World War Two, 50 Years On (R & J. Marks, Brisbane; 1994) 14-17.

- D Ober, J Sproats and R Mitchell, Saibai to Bamaga, The Migration from Saibai to Bamaga on the Cape York Peninsula, (Bamaga Island Council, Joe Sproats & Associates, Townsville; 2000) 14

- Queensland State Archives, Director of Native Affairs Office, SRS 505/1, Correspondence Files, File 9M/10, part 1, Administration Cape York Peninsula, Development of Northern Peninsula Area.

- D Ober, J Sproats and R Mitchell, Saibai to Bamaga, The Migration from Saibai to Bamaga on the Cape York Peninsula, (Bamaga Island Council, Joe Sproats & Associates, Townsville; 2000) 6-8

- Queensland, Native Affairs – Information contained in Report of Director of Native Affairs for the Twelve Months ended 30 June 1948 (1948) 22.

- D Ober, J Sproats and R Mitchell, Saibai to Bamaga, The Migration from Saibai to Bamaga on the Cape York Peninsula, (Bamaga Island Council, Joe Sproats & Associates, Townsville; 2000) 16-17.

- Queensland, Native Affairs – Information contained in Report of Director of Native Affairs for the Twelve Months ended 30 June 1949 (1949) 25; Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 24 July 1948, 675.

- Bamaga State High School, North of the Jardine, A Look at the Five Communities of the NPA (Bamaga State High School, Bamaga; 1997)

- "Seisia - town (entry 30370)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Queensland, Annual Report of Department of Community Services for 1986 (1987) 3; Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Community Services for 1987 (1988).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Seisia (Seisia Island) (State Suburb)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

Attribution

This Wikipedia article contains material from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community histories: Seisia. Published by The State of Queensland under CC-BY-4.0, accessed on 3 July 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seisia, Queensland. |