Sason

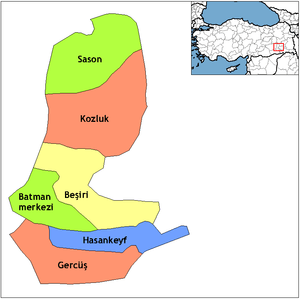

Sason (Armenian: Սասուն Sasun, Kurdish: Qabilcewz,[3] ;Arabic: قبل جوز; formerly known as Sasun or Sassoun) is a district in the Batman Province of Turkey. It was formerly part of the sanjak of Siirt, which was in Diyarbakır vilayet until 1880 and in Bitlis Vilayet in 1892. Later it became part of Muş sanjak in Bitlis vilayet, and remained part of Muş until 1927. It was one of the districts of Siirt province until 1993. The boundaries of the district varied considerably in time. The current borders are not the same as in the 19th century, when the district of Sasun was situated more to the north (mostly territory now included in the central district of Muş) [4]

Sason | |

|---|---|

Sason | |

| Coordinates: 38°22′49″N 41°23′43″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Batman |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Muzzafer Arslan (AKP) |

| • Kaymakam | Abdullah Özadalı |

| Area | |

| • District | 731.90 km2 (282.59 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Urban | 11,322 |

| • District | 31,475 |

| • District density | 43/km2 (110/sq mi) |

| Post code | 72500 |

| Website | www.sason.bel.tr |

Sasun, as it is called by Armenians, holds a prominent role in Armenian culture and history. It is the setting of Daredevils of Sassoun, Armenia's national epic. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was a major location of Armenian fedayi activities, who staged two uprisings against the Ottoman authorities and Kurdish tribes in 1894 and 1904. Sasun's Aramaic exonym "Arme" is also the origin of the exonym "Armenia". In the local elections of March 2019, Muzaffer Arslan was elected Mayor.[5] Abdullah Özadalı was appointed as Kaymakam.[6]

History

Historically the area was known as Sasun, part of the historical Armenian Highland. Sasun was in the Arzanene province of the ancient Armenian Kingdom. Later the region was ruled by the Mamikonian dynasty from around 772 until 1189/1190, when the Mamikonians moved to Cilicia after being dispossessed by Shah-Armen.[7]

Ottoman period

The region was eventually conquered by the Ottoman Empire, becoming part of the sanjak of Muş in Bitlis Vilayet, and continued to hold a substantial population of Armenians.[8] During this period, Sason was a federation of some forty Armenian villages, whose inhabitants were known as Sasuntsis (Armenian: Սասունցի).[8] Surrounded by fierce Kurdish tribes to whom they were often forced to pay tribute, the Sasuntsis were able to maintain an autonomy free of Turkish rule until the end of the 19th century when the Kurds themselves were finally brought under government control.[8][9] Proud warriors, the Sasuntsis made all their weapons and relied on nothing from the outside world.[8]

In 1893, some three to four thousand nomadic Kurds from the Diyarbakır plains entered Sason region. This incursion of nomads, who customarily used the mountain meadows of the area in summer for their herds, was harmful to the sedentary Armenians. Some Kurdish tribes were responsible for bringing economic ruin to the agrarian community of the Armenian villagers: they would steal livestock and demand that the Armenians should pay a second tax (that is, a separate tax in addition to the one Armenians paid to the Ottoman government).[10][11][12] When the Armenians decided to challenge extortion, a fight ensued and a Kurd was killed. Using the Kurd's death as a pretext by describing that a revolt had taken place, Turkish officials endorsed a Kurdish revenge attack against the Armenians of Sason.[13]

The Kurds, however, were successfully driven off by the armed Armenian villagers, but that success was then seen as a possible threat by the Ottoman authorities. In 1894, the villagers refused to pay taxes unless the Ottoman authorities adequately protected them against renewed Kurdish raids as well as extortion. Instead, the government sent a force of about 3,000 soldiers and Kurdish irregulars to disarm the villagers, an event which ended in a general massacre of between 900 and 3,000 men, women and children. The "Sasun affair" was widely publicised and was investigated by representatives from the European Powers, resulting in demands that Ottoman Turkey initiate reforms in the six "Armenian vilayets". Abdul Hamid II's response to those demands culminated in the anti-Armenian pogroms of 1895 and 1896.[14]

As part of the Hamidian massacres, McDowall estimates at least 1,000 Armenian villagers were slain in the Sason atrocity,[15] all of which was instigated by the buildup of Ottoman troops in early 1894.[16] Officials and military officers involved in the Sason massacres were decorated and rewarded.[17]

Modern Sason

Today, most of Sason's population is Kurd and Arab. An Armenian minority may still exist (in 1972 there were estimated to be some 6,000 Armenian villagers in the region).[18]

Culture

The area was the setting for the Armenian epic Sasna Tsrer (Daredevils of Sassoun), which was rediscovered and first partly written down in 1873. It is better known as Sasuntsi Davit ("David of Sasun").[8] This epic dates from the time of the invasion of Armenia by the Caliphs of Egypt (about 670), in which the Armenian folk hero of the same name drives foreign invaders from Armenia.[19]

See also

- Sasun Resistance (1894)

- Sasun Uprising (1904)

References

- "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Adem Avcıkıran (2009). Kürtçe Anamnez Anamneza bi Kurmancî (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). p. 56. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Thierry, J.M., Sasun. Voyages archéologiques, Revue des études arméniennes 23, 1992, p.320; Verheij, Jelle. ’Les frères de terre et d'eau’ : sur le rôle des Kurdes dans les massacres arméniens de 1894-1896", in: Bruinessen, M. van & Blau, Joyce (eds), Islam des Kurdes (special issue of Les Annales de l'Autre islam 5, Paris, 1998) p.239

- "Batman Sason Seçim Sonuçları - 31 Mart 2019 Yerel Seçimleri". www.sabah.com.tr. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- "Kaymakam Abdullah Özadalı". www.sason.gov.tr. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Hewsen, Armenia, p. 206.

- Hewsen, Armenia p. 167.

- Balakian, Peter. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. New York: HarperCollins. p. 54. ISBN 0-06-055870-9.

- Eliot, Charles. Turkey in Europe, p.405. 1908.

- Quataert, Don. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, p.880. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-57455-2

- Balakian, pp. 54-55.

- Hewsen. Armenia, p. 231.

- White, Paul J. Primitive Rebels Or Revolutionary Modernisers?, p.60-61. Zed Books, 2000. ISBN 1-85649-822-0

- Kaiser, Hilmar. Imperialism, Racism, and Development Theories, p.6. Gomidas Institute, 1997. ISBN 1-884630-02-2

- Chisholm, Hugh. The Encyclopædia Britannica, p.568. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co., 1910.

- Hewsen. Armenia, p. 268.

- Toumanian, Hovhannes. David of Sassoun (Armenian and English version ed.). Oshagan Publishers. pp. 7–8.