Royal Netherlands Army

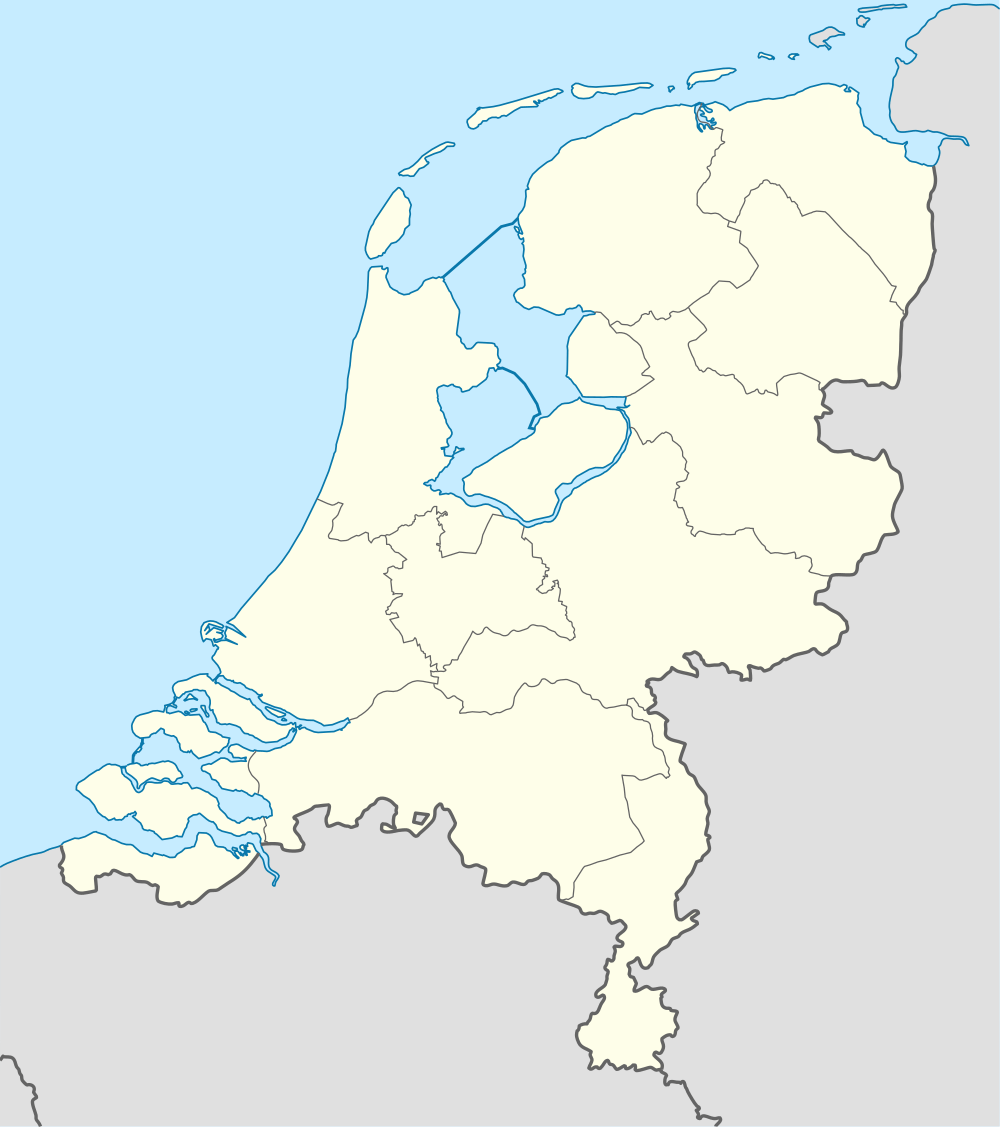

The Royal Netherlands Army (Dutch: Koninklijke Landmacht) is the land forces element of the military of the Netherlands.

| Royal Netherlands Army | |

|---|---|

| Koninklijke Landmacht | |

Emblem of the Royal Netherlands Army | |

| Active | January 9, 1814 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | 22,850 (2020)[1] • 18,850 active • 4,000 reserve |

| Part of | Armed forces of the Netherlands |

| Headquarters | Kromhoutkazerne, Utrecht |

| Engagements | List of engagements

|

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Lt Gen Martin Wijnen[2] |

| Deputy commander | Maj Gen Kees Matthijssen[3] |

| Army Adjutant | WO Ad Koevoets[4] |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Logo |  |

Though the Royal Netherlands Army was raised on 9 January 1814, its origins date back to 1572, when the Staatse Leger was raised – making the Dutch standing army one of the oldest in the world. It fought in the Napoleonic Wars, World War II, the Indonesian War of Independence, and the Korean War and served with NATO on the Cold War frontiers in West-Germany from the 1950s to the 1990s.[5]

Since 1990, the army has been sent into the Iraqi War (from 2003) and into the War in Afghanistan, as well as deployed in several United Nations' peacekeeping missions (notably with UNIFIL in Lebanon and UNPROFOR in Bosnia-Herzegovina and MINUSMA in Mali).[6]

The tasks of the Royal Netherlands Army are laid out in the Constitution of the Netherlands: defend the territory of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (including the Dutch Caribbean) and of its allies, protect and advance the international legal order and to support the (local) government in law enforcement, disaster relief and humanitarian aid, both nationally and internationally.[7] The supreme authority over the armed forces of the Netherlands is exercised by the government (consisting of the King and the cabinet ministers); there is thus no constitutional supreme commander. However, army personnel does swear allegiance to the Dutch monarch.[8]

Dutch army doctrine strongly emphasises international co-operation.[9] The Netherlands are a founding member of, and strong contributor to NATO, while closely co-operating with fellow member states during European Union-led missions as well. Moreover, the successful Dutch-German military co-operation is seen as a harbinger of European defence integration, facing fewer linguistic and cultural issues than the comparable Franco-German Brigade.[10] In 2014, the 11 Airmobile Brigade was integrated into the Rapid Forces Division;[11] in 2016, the Dutch-German 414 Tank Battalion was integrated into the 43rd Mechanised Brigade, which was in turn integrated 1st Panzer Division.[10][12] Additionally, the German Air Defence Missile Group 61 (German: Flugabwehrraketengruppe 61) was integrated into the Dutch Joint Ground-based Air Defence Command in 2018.[13]

History

Origins

The Royal Netherlands Army was raised on 9 January 1814, but its origins date back to the founding of the Staatse Leger (the Army of the Dutch States) in 1572: the creation of one of the first modern standing armies. Under the command of famous commanders such as Maurice of Orange and William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg, the army developed into one of the best-organised and best-trained armies of the 17th and early 18th centuries.[14][5] The innovative army underwent a thorough process of professionalisation under their command including revolutionary foot drill and siege tactics, proven effective during sieges such as the Battle of Nieuwpoort.[15][16]

The Dutch States Army of the Dutch Republic saw action in the Eighty Years' War, the Dano-Swedish War, the Franco-Dutch War, the Nine Years' War, the War of Spanish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession, and the French Revolutionary Wars.[14]

French period (1795–1814)

With the French conquest of the Netherlands, the Staatse Leger was replaced by the army of the Batavian Republic in 1795, which in turn was replaced by the army of the Kingdom of Holland in 1806. This army fought beside the French, to repel the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland in 1799 and to wage several campaigns in Germany, Austria, and Spain between 1800 and 1810; particularly notable were the engagements of the Horse Artillery (Korps Rijdende Artillerie) at the Battle of Friedland in 1807, the capture of the city of Stralsund in 1807 and 1809, and the participation of the Dutch brigade in the Peninsular War between 1808 and 1810.[17] The independent army was disbanded in 1810, when Napoleon decided to integrate the Netherlands into France ("La Hollande est reunie à l'Empire"): Dutch military units became part of the Grande Armée (the present-day French 126th Infantry Regiment has Dutch origins).[18] Dutch military elements participated in the disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812, and the actions of the Pontonniers company under Captain Benthien at the Berezina River (Battle of Berezina) are especially noteworthy. New research points out that, contrary to long-held belief, around half of the Dutch contingent of the Grande Armée survived the Russian Campaign.[19]

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1814–1914)

Following the return of William I of the Netherlands in Scheveningen in 1813, an independent Dutch army was resurrected by the new Kingdom of the United Netherlands in 1814, following the Orangist uprising against Napoleonic rule in 1813. This new force, the Netherlands Mobile Army, comprised of several militias and veterans of the Staatse Leger, formed an integral part of the allied army during the Hundred Days campaign that culminated in the Battle of Waterloo.[20] Units such as Baron Chassé's were key in securing victory for the allied army. The army was involved in various conflicts since 1814, including the Waterloo campaign (1815) and different colonial wars (1825–1925).[21]

Furthermore, the army was deployed during the Belgian Revolution, from 1830 to 1832, to restore order in the southern provinces. After initial Dutch military success and widespread Belgian defeat during battles of the Ten Days' Campaign, the Belgian rebels appealed to France for military support. The severely outnumbered Dutch troops were forced to retreat when the French agreed to send reinforcements.[22]

World wars (1914–1945)

The Netherlands continued the policy of neutrality during World War I. This stance arose partly from a strict policy of neutrality in international affairs that started in 1830 with the secession of Belgium. Dutch neutrality was not guaranteed by the major powers in Europe however, nor was it a part of the Dutch constitution. The country's neutrality was based on the belief that its strategic position between the German Empire, German-occupied Belgium, and the British guaranteed its safety. The Dutch military strategy was aimed exclusively at defence and rested to a large extent on the Dutch Water Line, a defensive ring of rivers and lowland surrounding the core Dutch region of Holland, that could be inundated.[23][5]

At the beginning of the Second World War, the I Corps was the force strategic reserve and was located in the Vesting Holland, around The Hague, Leiden, Haarlem and in the Westland.[24] The German invasion posed a complete surprise for the army command and shocked the Dutch population. While the Royal Netherlands Army initially managed to slow down the German advance and fought back in intense battles, such as the Battle for The Hague, the Battle of Rotterdam and the Battle of the Afsluitdijk, the devastating German bombing of Rotterdam and the threat of bombing the city of Utrecht forced the Dutch supreme command to capitulate.[25]

The Royal Netherlands army was disbanded during the German occupation, however army personnel continued the battle against the German occupiers during the war. Army resistance began to rise again with the formation of the Princess Irene Brigade and No. 2 (Dutch) Troop (predecessor to the Korps Commandotroepen) as part of the Free Dutch Forces in exile, and with army personnel active in the Dutch resistance.[26][27] In the East, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army was defeated by the Japanese in 1942; few elements managed to escape. Today's army grew out of the wartime force, starting with the liberation of parts of the Netherlands in 1944; the Dutch had plans to contribute a 200,000 strong army to the defeat of Germany and Japan.[28]

Decolonisation and Cold War (1945–1991)

Dutch East Indies

Between 1945 and 1949, the Royal Netherlands Army, which originally used mainly war volunteers but later was heavily dependent on conscripts, was deployed to the Dutch East Indies during the Indonesian War of Independence. In order to restore authority, order and peace in the Dutch East Indies, the expeditionary land force First Division 7 December was established in 1946.[29] Approximately 25,000 volunteers and 95,000 conscripts were deployed to the East during the conflict, 4,751 servicemen were killed.[30]

Cold War

Army personnel was part of the 4,748 men strong Nederlands Detachement Verenigde Naties during the Korea War (1950–1953). This detachment was comprised of personnel of the army, the Royal Netherlands Navy and the Netherlands Marine Corps, and fought against the communist troops of the People's Republic of China and North Korea. 122 soldiers were killed in action, 3 soldier went missing in action.[31]

The I (Netherlands) Corps stood watch alongside its NATO allies in Germany during the Cold War. The corps consisted of three divisions during the 1980s, the 1st, 4th, and 5th (reserve) divisions.[32] It was part of the NATO Northern Army Group. The corps's war assignment, as formulated by Commander, Northern Army Group (COMNORTHAG), would be to:[33]

- Assume responsibility for its corps sector and relieve 1st German Corps forces as soon as possible.

- Fight the covering force battle in accordance with COMNORTHAG's concept of operations.

- In the main defensive battle: (1) hold and destroy the forces of the enemy's leading armies conventionally as far east as possible, maintaining cohesion with 1 (GE) Corps; (2) in the event of a major penetration affecting 1 (NL) Corps sector, be prepared to hold the area between the roads A7 and B3 and to conduct a counterattack according to COMNORTHAG's concept of operations.

- Maintain cohesion with LANDJUT and secure NORTHAG's left flank in the Forward Combat Zone.

Dutch army troops have deployed to Lebanon as part of an international protection force since 1979 War in Lebanon, 1979–1985 UNIFIL. Of the 9,084 soldiers who served in Lebanon, 9 soldiers were killed in action.[34]

Recent history (1991–present)

The Fall of the Iron Curtain and the ensuing end of the Cold War has had a significant impact on the Dutch armed forces as a whole, but on the army in particular. Mandatory conscription was suspended and surplus equipment deemed unnecessary was sold. An airmobile brigade was formed and co-operation with allied countries, Germany in particular, was intensified. The I (NL) Corps was reduced to the First Division 7 December in 1995, which became part of the newly established I. German/Dutch Corps, and consequently the division headquarters itself was disbanded.[35] In addition, the army increasingly concentrated on peace-keeping and peace-enforcing operations and has been involved in several operations in the former Yugoslavia (1991–present), but also in Cambodia (1992–1994), Haiti (1995–1996), Cyprus (1998–1999), Eritrea and Ethiopia (2001), and most recent in Iraq (2003–2005), Afghanistan (2002–present), Chad (2008–2009) and Mali (2014–2019).[6]

As mentioned, peace dividend was collected throughout the 1990s, 2000s and early 2010s resulting in a dramatic downsizing in both budget and size. Of a total of 445 Leopard 2 MBTs originally purchased, 114 tanks and 1 turret were sold to Austria, 100 to Canada, 57 to Norway, 1 driver training tank and 10 turrets to Germany and 38 to Portugal (1 driver training tank).[36][37] On April 8, 2011 the Dutch Ministry of Defense dissolved the last tank unit and sold the remaining Leopard tanks due another series of large budget cuts while also dismissing 6,000 servicemen and women.[38] On May 18, 2011 the last Leopard 2 fired the final shot at the Bergen-Hohne Training Area.[39] In 2014, the Dutch defence budget hit a new low, 7.4 billion euros (1.09% of GDP), resulting in the combat readiness of both personnel and equipment being subpar.[40][41] The negative trend was broken from 2015 onwards due to a perceived shifting international security situation. The attitude towards defence changed, mainly caused by increasing tensions with Russia (caused by the downing of the MH17 flight and the annexation of Crimea) and the rise of the Islamic State, resulting in the defence budget seeing an increase of over 50 percent between 2014 and 2020, amounting to 11.04 billion euros (1.35% of GDP) in 2020.[42]

Bosnia

Dutch army personnel was deployed to Bosnia between 1994 and 1995 to, as part of the UN peace force UNPROFOR, to restrain the escalating ethnic violence of the Bosnian War.[43] Three infantry batallion (known as Dutchbats) of the, at the time, recently established 11 Air Assault Brigade were sequentially deployed to guard the United Nations Safe Areas of any possible threats. This mission became infamous following the Siege of Srebrenica and the ensuing Srebrenica massacre.[44] Bosniak-Serb troops under the command of general Ratko Mladic, sentenced to life imprisonment on accounts of participating in genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in 2017,[45] invaded the enclave of Srebrenica and subsequently deported and massacred a large share of the present muslim men and boys.[46]

Iraq

A contingent of 1,345 troops (comprising Army and Dutch Marines, supported by Royal Netherlands Air Force helicopters) was deployed to Iraq in 2003, based at Camp Smitty near As Samawah (Southern Iraq) with responsibility for the Muthanna Province, as part of the Multinational force in Iraq.[47] On June 1, 2004, the Dutch government renewed their stay through 2005.[48] The Netherlands pulled its troops out of Iraq in March 2005, leaving half a dozen liaison officers until late 2005.[49] The Netherlands lost 2 soldiers in separate attacks.[48]

From 2015 until the spring of 2018, Dutch special operations forces (KCT and NLMARSOF) deployed advice and assist (A&A) teams to northern Iraq in co-operation with the Belgian Special Forces Group.[50] During this deployment, they provided support to Kurdish Peshmerga and Iraqi Army forces before, during and after operations in the battle against ISIL, as part of the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve.[51] The Netherlands currently deploy approximately 60 troops to Iraq.[52]

Afghanistan

Between 2001 and 2003, a reinforced army company was deployed to Afghanistan to provide support in maintaining public order, and providing security in and around the capital Kabul.[53] In addition, military assistance was provided to the Afghan National Army and to local security troops. The troops were deployed under the command of NATO's International Security Assistance Force mission.

Between 2006 and 2010, the Netherlands deployed a large number of personnel to southern Afghanistan.[54] Together with the Australian armed forces, Dutch forces were assigned the province of Uruzgan as their area of operations. In mid 2006, Dutch special forces of the Korps Commandotroepen as part of the Deployment Task Force successfully deployed to Tarin Kowt to lay the ground for the increasing numbers of engineers who were due to build a vast base there.[55] By August 2006 the Netherlands deployed the majority of 1,400 troops to Uruzgan province in southern Afghanistan at Kamp Holland in Tarin Kowt (1,200) and Kamp Hadrian in Deh Rahwod (200).[54][56] PzH 2000 self-propelled artillery pieces were deployed and used in combat for the first time.[57] The Dutch forces operated under the command of the ISAF Task Force Uruzgan and were involved in some of the more intensive combat operations in southern Afghanistan, including Operation Medusa and the Battle of Chora.[58][57] On 18 April 2008, the second day of his command, the son of the Commander of the Royal Netherlands Army Lieutenant-general Peter van Uhm, Lieutenant Dennis van Uhm, was one of two servicemen killed by a road side explosion.[59] As of 1 September 2008, the Netherlands had a total of 1,770 troops in Afghanistan not including special forces troops.[60] In total, 25 Dutch servicemen were killed in action during the deployment.[61] All Dutch troops were withdrawn from Afghanistan by August 2010.[62]

Since 2015, 160 Dutch troops comprised of special operations forces of the Korps Commandotroepen (rotated with NLMARSOF) and multiple support elements are deployed to the Afghan city of Mazar-e-Sharif as part of NATO's Resolute Support Mission.[63] The Dutch troops co-operate with personnel of the German Kommando Spezialkräfte as part of the German-Dutch lead Special Operations Advisory Team (SOAT). The SOAT provides advice and assistance during operations to an Afghan police tactical unit, the Afghan Territorial Force-888 (ATF-888).[64] The SOAT has been granted authority to deploy in the entirety of Afghanistan.[65]

Mali

Special forces of the Korps Commandotroepen have been deployed to Mali since 2014 as part of the UN-mission MINUSMA.[66] The primary task of the Dutch forces was to gather intelligence concerning local Islamist groups and to protect the people of Mali against radical Islamist groups.[67] Rotations since 2016 were comprised of personnel of 11th Airmobile Brigade and 13th Light Brigade. On 6 July 2016, two servicemen of 11 Airmobile Brigade were killed during a mortar firing exercise, a third serviceman was severely wounded.[68] The incident lead to the resignation of the minister of Defence Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert and Chief of Defence Tom Middendorp after a critical report by the Dutch Safety Board found that the safety-standards were subpar.[69][70] The Netherlands have ended their troop contribution to the peacekeeping mission in May 2019 to send troops to Afghanistan instead.[71]

Lithuania

The cabinet of the Netherlands announced in 2016 that they will be contributing troops to the NATO Enhanced Forward Presence mission in Lithuania.[72] Their presence is intended to protect and reassure countries on NATO's eastern flank, the Baltic countries and Poland in particular, of their security following increased political tensions sparked by Russia's annexation of Crimea and the War in Donbass.[73] The Dutch contribution currently equates to approximately 270 troops, integrated into a multinatinational battle group that is headed by Germany.[74] Each rotation is comprised of armoured infantry companies equipped with CV9035NL IFVs and Boxer AFVs, or artillery companies equipped with PzH 2000NL self-propelled howitzers.[75]

Current structure

The core fighting element of the army consists of three brigades: 11 Airmobile Brigade, 13 Light Brigade and 43 Mechanised Brigade.[76] The number of full-time professional personnel is 22,850, in addition to around 4,000 reservists.[1] The Royal Netherlands Army is a volunteer force; compulsory military service has not been abolished but has been suspended.[77] The other three services, the (Royal Netherlands Navy, Royal Netherlands Air Force and Royal Marechaussee), are fully volunteer forces as well.

_Corps.svg.png)

Traditions

Besides the hierarchical organisation, the Royal Netherlands Army upholds a traditional organisation in which a distinction exists between arms and services. This organisations is purely ceremonial. Generally speaking, combat and combat support units are organised in arms, and support units are organised in services.[78] There are two exceptions: the Engineers and the Signals Service.

The arms and services can in turn be further divided into one, or multiple regiments. These administrative organisations safeguard the traditions of the operational units. Before the Second World War, regiments were merely given a number, with the exception of the Grenadiers and Jagers regiments. Since the 1950s however, the regiments were given a historical name. The function of a regiment is strictly ceremonial, and is intended to increase esprit de corps.[79]

Arms

The Royal Netherlands Army consists of the following arms, and subsequent regiments and corps:[78]

| Regiment | Unit | Year | Insignia | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infantry Arm (Foot guards) | ||||||

| Garderegiment Grenadiers en Jagers | 11 Infantry Battalion | 1995 |   | Established in 1995 through amalgamation of two regiments which were formed in 1829. | ||

| Garderegiment Fuseliers Prinses Irene | 17 Armoured Infantry Battalion | 1941 |  | Established in 1941. | ||

| Infantry Arm (Line infantry) | ||||||

| Regiment Infanterie Johan Willem Friso | 44 Armoured Infantry Battalion | 1813 |  | Former 1st and 9th Infantry Regiment, established in 1813. | ||

| Regiment Infanterie Oranje Gelderland | 45 Armoured Infantry Battalion | 1813 |  | Former 5th and 8th Infantry Regiment, established in 1813. | ||

| Regiment Limburgse Jagers | 42 Armoured Infantry Battalion | 1813 |  | Former 2nd, 6th and 11th Infantry Regiment, established in 1813. | ||

| Regiment Van Heutsz | 12 Infantry Battalion | 1832 |  | Maintains traditions of the disbanded Royal Netherlands East Indies Army and the Netherlands Detachment United Nations which fought in the Korean War, established in 1832 although origins date back to 1814. | ||

| Korps Nationale Reserve | • 20 National Reserve Battalion • 30 National Reserve Corps Battalion • 10 National Reserve Corps Battalion | 1914 |  | Maintains traditions of the Volunteer Landstorm, established in 1914. | ||

| Korps Commandotroepen | Korps Commandotroepen | 1942 |  | Successor to No. 2 (Dutch) Troop and Korps Speciale Troepen, established in 1942. | ||

| Regiment Stoottroepen Prins Bernhard | 13 Infantry Battalion | 1944 |  | Established in 1944 by amalgation of several resistance groups. | ||

| Regiment Infanterie Menno van Coehoorn | Disbanded | 1950 | Former 3rd Infantry Regiment, disbanded in 1997. | |||

| Regiment Infanterie Chassé | Disbanded | 1950 |  | Former 7th and 10th Infantry Regiment, disbanded in 1995. | ||

| Cavalry Arm | ||||||

| Regiment Huzaren Van Boreel | • 11 Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron • 42 Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron • 43 Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron • 104 JISTARC Reconnaissance Squadron • 414 Tank Battalion | 1813 | .jpg) | Former 4th Hussars Regiment. Established in 1813 while its origins date back to 1585. – Reconnaissance/ISTAR | ||

| Regiment Huzaren Prins Alexander | Disbanded | 1950 |  | Former 3rd Hussar Regiment, the regiment was disbanded in November 2007. The maintenance of regimental traditions was transferred to the Regiment Huzaren van Boreel. The regiment was permanently disbanded by Royal Decree on the 2nd June 2016. | ||

| Regiment Huzaren Van Sytzama | Re-established, traditional duties only | 1951 |  | Former 1st Hussar Regiment, disbanded in May 2011. The maintenance of regimental traditions was transfered to the Regiment Huzaren van Boreel. The regiment was formally re-established by Royal Decree on the 2nd June 2016. | ||

| Regiment Huzaren Prins van Oranje | Re-established, traditional duties only | 1979 |  | Former 2nd Hussar Regiment, disbanded in September 2012. The maintenance of regimental traditions was transfered to the Regiment Huzaren van Boreel. The regiment was formally re-established by Royal Decree on the 2nd June 2016. | ||

| Artillery Arm | ||||||

| Korps Veldartillerie | • A Battery of 41 Artillery Battalion • B Battery of 41 Artillery Battalion • D Battery of 41 Artillery Battalion | 1677 |  | Field artillery corps, established in 1677. Currently operates PzH 2000NL self-propelled howitzers. | ||

| Korps Rijdende Artillerie | C Battery of 41 Artillery Battalion | 1793 |  | Horse artillery corps, established in 1793. Currently operates 120mm Rayé Tracté heavy mortars. | ||

| Korps Luchtdoelartillerie | 13th Air Defense Battery | 1917 |  | Air defence artillery corps, established in 1917. Currently operates NASAMS 2 medium range surface-to-air missiles, Fennek Stinger Weapon Platforms, and TRML systems. | ||

| Engineer Arm | ||||||

| Regiment Genietroepen | • 11 Engineer Company • 41 Armoured Engineer Battalion • 11 Armoured Engineer Battalion • 101 Engineer Battalion | 1748 |  | Established in 1748. | ||

| Signals Arm | ||||||

| Regiment Verbindingstroepen | • Command & Control Support Command • 102 Electronic Warfare Company | 1874 |  | Established in 1874. | ||

Infantry

Each infantry regiment of the Royal Netherlands Army consists of a single battalion. The current order of battle includes a total of seven infantry battalions – of these, two are classed as foot guards and the remainder as line infantry.[80]

The staff support companies of 11 Airmobile Brigade, 13 Light Brigade and 43 Mechanised Brigade are part of the Garderegiment Grenadiers en Jagers, the Garderegiment Fusiliers Prinses Irene and Regiment Infanterie Johan Willem Friso, respectively.

Cavalry

The cavalry arm currently consists of one active regiment. Prior to 2012, the army also included armoured regiments equipped with main battle tanks. One of these, the Regiment Huzaren Prins Alexander, was disbanded in 2007 due to budget cuts. The other two, the Regiment Huzaren Van Sytzama (former 1st Hussar Regiment) and the Regiment Huzaren Prins van Oranje (former 2nd Hussar Regiment) were disbanded, along with the army's full armoured capability, in 2012 as a result of further cuts to the Dutch defence budget.[81]

In 2016, a German armoured unit, 414 Panzer Battalion, was attached to the Dutch 43 Mechanised Brigade, at the same time becoming a combined German-Dutch unit, with one of the three tank companies and part of the staff and support companies manned with Dutch troops.[82]

Services

The services (Dutch: Dienstvakken) consist of the logistical service, which comprises four regiments, and four stand-alone support services. The Royal Netherlands Army consists of the following services and regiments:[78]

| Regiment | Unit | Year | Insignia | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistical Service | ||||||

| Korps Militaire Administratie | Military Administration Corps | 1795 |  | Established in 1795. | ||

| Regiment Geneeskundige Troepen | • 400 Medical Battalion • 11 Medical Company • 13 Medical Company • 43 Medical Company | 1869 |  | Established in 1869. | ||

| Regiment Bevoorradings- en Transporttroepen | • Supply and Transport Command • 11 Supply Company | 1905 |  | Established in 1905. | ||

| Regiment Technische Troepen | • 11 Maintenance Company • 13 Maintenance Company • 43 Maintenance Company • Land Materiel Logistic Command | 1941 |  | Technical troops, established in 1941. | ||

| Other Services | ||||||

| Dienstvak Technische Staf | • 11 Maintenance Company • 13 Maintenance Company • 43 Maintenance Company • Land Materiel Logistic Command | 1954 |  | Academically educated technical engineers, all officers. Focused on acquiring new equipment and performing technical research, established in 1954. | ||

| Dienstvak Militair Juridische Dienst | Military Legal Service | 1949 | Established in 1949. | |||

| Dienstvak Militair Psychologische en Sociologische Dienst | Psychological and Sociological Service | 1973 |  | Established in 1973. | ||

| Dienstvak van de Lichamelijke Oefening en Sport | Physical Education and Sports Organisation | 2004 | Established in 2004. | |||

Uniforms

The Royal Netherlands Army uniform has multiple categories, ranging from ceremonial uniforms to combat dress to evening wear. In addition, the (special) service dress uniform and mess dress uniform can both be worn in a tropics colourway.[83]

There are four main uniform categories:

- Combat uniform (Dutch: Gevechtstenue, GVT): The day-to-day combat uniform, is known as Gevechtstenue (GVT M93) and consists of a Disruptive Pattern Material (DPM) jacket and trousers with additional items such as thermals and waterproofs that can be worn underneath. Army combat uniforms are fitted with a distinctive unit insignia on the right arm, while the Dutch flag and the wearer's regiment or corps are worn on the left arm. To optimise the effectiveness of the uniform, multiple camouflage patterns are in use:

- Woodland: Further developed version of the British Disruptive Pattern Material (DPM) camouflage pattern. Optimised for use in wooded terrain in Western Europe and the standard pattern for personnel in the Netherlands.

- Desert: Increasing amount of deployments in desert like environments, such as Iraq and Afghanistan, lead to the implementation of the Desert combat uniform. The desert combat uniform utilises the regular combat uniform, while using the American Desert Camouflage Pattern.

- Jungle: The jungle combat uniform utilises the regular combat uniform, in a five-coloured camouflage pattern which is optimised for deployments in tropical environments. The jungle uniform is often used by personnel undergoing jungle training, and units stationed in the Dutch Caribbean.

- MultiCam: Since the regular combat uniform no longer always qualifies for contemporary operations, personnel deploying to foreign countries is provided with interim combat uniforms in the MultiCam camouflage pattern.[84] In addition, the Korps Commandotroepen has implemented uniforms in MultiCam as their standard uniform since 2017.[85] Regular units use the interim uniforms until combat clothing in the newly developed Netherlands Fractal Pattern is distributed, between 2020 and 2022.

- Service dress uniform (Dutch: Dagelijks tenue, DT): The service dress uniform is used for everyday office, barracks and non-field duty purposes. The uniform was designed by the famous couturier Frans Molenaar and entered service in 2000. It consists of trousers, a jacket, dress shirt, neck tie and headgear (beret, peaked cap or side cap), in a gray-green fabric.

- Special dress uniform (Dutch: Gelegenheidstenue, GLT): This uniform is worn for certain formal occasions. It consists of the garments of the service dress uniform, differing by the white dress shirt, black neck tie, white gloves, decorations worn in Prussian arrangement, while officers wear an orange sash around the waist.

- Mess dress uniform (Dutch: Avondtenue, AT): The mess dress uniform is worn during formal occasions, such as a diners or a ball and consists of a black smoking, complemented with a peaked cap and miniature medals.

- Full dress uniform (Dutch: Ceremonieel tenue, CT): Each regiment and corps within the army has its own ceremonial uniform, worn during ceremonies and special occasions.

Soldier wearing the Field Artillery Corps ceremonial uniform during the firing of salute shots on Prinsjesdag.

Soldier wearing the Field Artillery Corps ceremonial uniform during the firing of salute shots on Prinsjesdag. Hussar of 414 Tank Battalion wearing a tank overall in the new Netherlands Fractal Pattern.

Hussar of 414 Tank Battalion wearing a tank overall in the new Netherlands Fractal Pattern. Jungle combat uniform worn by 11 Airmobile Brigade servicemen as part of de contingent in the Dutch Caribbean.

Jungle combat uniform worn by 11 Airmobile Brigade servicemen as part of de contingent in the Dutch Caribbean. Standard combat uniform in the Disruptive Pattern Material camouflage pattern.

Standard combat uniform in the Disruptive Pattern Material camouflage pattern. Knights of the Military William Order Kenneth Mayhew, Major Marco Kroon and Lieutenant Colonel Gijs Tuinman, the last both wearing the special dress uniform.

Knights of the Military William Order Kenneth Mayhew, Major Marco Kroon and Lieutenant Colonel Gijs Tuinman, the last both wearing the special dress uniform.

Military music

For a long time, military music was used as a means of communication on the battlefield for a long time. Nowadays, military music plays an important role during military cermonies, such as changes of command and enlistment ceremonies, and national events such as Prinsjesdag and the annual Remembrance of the Dead ceremony on the 4th of May. In addition, the military bands provide the musical accompaniment for the presentation ceremony of letters of credence. The military bands are all comprised of active duty personnel, with the exception of the National Reserve Corps Fanfare which is comprised of national reserve personnel. Currently, there are four active military bands and fanfare orchestras within the Royal Netherlands Army:[86]

- Royal Military Band "Johan Willem Friso"

- National Reserve Corps Fanfare Brass

- Regimental Fanfare Orchestra of the Grenadiers' and Rifles' Guards

- Fanfare Orchestra "Bereden Wapens" of the RNA Cavalry

Colours and standards

All regiments and corps are granted a colour (Dutch: vaandel) or standard (Dutch: standaard). The colours and standards form the emboidement of the history and character of the respective regiment or corps. The standards are smaller in size because of a historical reason: horseback units would often struggle with the large sized poles of the regular colors, and therefore chose to wield a shorter version. To this day, the mounted units of the Royal Netherland Army, such as cavalry, field artillery and horse artillery, utilise the smaller sized standards. The Royal Marechaussee, which used to be a mounted unit of the Royal Netherlands Army, owns a standard as well.[87]

In contrast to the functional use of colours and standards in the past, during which they served as landmarks on the battlefield, their contemporary role has been greatly reduced. However, they continue to play an important rule during various military ceremonies. For example, soldiers swear the oath of enlistment while holding the respective colour or standard. Moreover, the colours and standards constitute an important connection between military units and the Royal House of the Netherlands. Only the sovereign can grant a military unit a colour or standard, therefore the royal cypher of the monarch that granted the regiment its (original) colour is displayed. In addition, the colours and standards are often inscripted with (historical) battle honours. By prominently displaying them, the aim is to add to the esprit de corps, uphold the collective memory and serve as inspiration for future actions of the respective unit.[87]

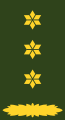

Ranks and insignia

The ranks of the Royal Netherlands were established by Royal Decree of Queen Juliana in 1956.[88] Each regiment and corps has a distinctive cap badge and beret. Many units also call soldiers of different ranks by different names, for example a NATO OR-1 private is called a hussar (Dutch: huzaar) in cavalry regiments and a cannoneer (Dutch: kannonier) in artillery units.[89]

- Officers

| NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student officer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enlisted or NCO rank plus Royal Military Academy logo indicating cadet's career | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Generaal | Luitenant-generaal | Generaal-majoor | Brigadegeneraal | Kolonel | Luitenant-kolonel | Majoor | Kapitein/Ritmeester | 1e Luitenant | 2e Luitenant | Vaandrig/Kornet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English equivalent | General | Lieutenant General | Major General | Brigadier General | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | Officer Cadet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Enlisted

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adjudant-onderofficier | Sergeant-majoor/ Opperwachtmeester |

Sergeant der 1e klasse/ Wachtmeester der 1e klasse |

Sergeant/Wachtmeester | Korporaal der 1e klasse | Korporaal | Soldaat/Huzaar/ Kanonier der 1e klasse |

Soldaat/Huzaar/ Kanonier der 2e klasse |

Soldaat/Huzaar/ Kanonier der 3e klasse | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English equivalent | Warrant Officer | Sergeant Major | Staff sergeant | Sergeant | Master corporal | Corporal | Lance Corporal | Private first class | Private | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Equipment

Infantry

The Royal Netherlands Army's basic weapon is the Colt C7NLD or Colt C8NLD assault rifle, produced by Colt Canada (formerly Diemaco). The weapons received an extensive update in 2009: the rifle's black furniture was replaced by dark earth furniture. New parts include a new retracting stock, the Diemaco IUR with RIS rails for mounting flashlights and laser systems, and a vertical foregrip with built-in bipod; the thermold plastic magazines have now become brown in color. The ELCAN sighting system has also disappeared in favour of the Swedish made Aimpoint CompM4 red dot sight. In addition, the weapon can be enhanced further utilising the Picatinny rail with attachments such as the Heckler & Koch UGL under-barrel grenade launcher.[90] Special operations forces of the Korps Commandotroepen choose to use modified HK416 assault rifles and HK417 designated marksman rifles.[91] The standard secondary weapon across all branches of the Armed forces of the Netherlands is the Austrian-made Glock 17 pistol.[92]

Sniper groups (Dutch: Schutter Lange Afstand) are equipped with Accuracy International Arctic Warfare Magnum, currently being replaced by its successor Accuracy International AX308, and Barrett M82 sniper rifles.[93][94][95] Support fire is provided by the FN Minimi light machine gun (LMG), the FN MAG general purpose machine gun (GPMG) and FN M2 QCB heavy machine gun (HMG), while indirect fire support is provided by M6 60mm or L16 81mm mortars.[96][97][98][99]

Cavalry

The army's main battle tank is the Leopard 2.[100] The Swedish-made CV90 (designated internally as CV9035NL) is the infantry fighting vehicle of the army, supported on the battlefield by Boxer MRAV armoured fighting vehicles.[101][102] Reconnaissance units utilise the light armoured Fennek reconnaissance vehicle.[103]

Artillery and air defence

The Fire Support Command currently operates two artillery systems: three batteries equipped with Pantserhouwitser 2000NL self-propelled howitzers and one battery equipped with 120mm Rayé Tracté heavy mortars.[104][99] Air defence is provided by the modernised MIM-104 Patriot long-range air defence system operated by the Joint Land-based Air Defence Command.[105][106] Both the PAC-2 surface-to-air missile and PAC-3 anti-ballistic missile are in use.[106] In addition, army personnel operate NASAMS 2 medium-range surface-to-air missiles, Fennek Stinger Weapon Platforms, and TRML systems. These systems are operated combinedly in the Army Ground Based Air Defence System (AGBADS).[107]

(Protected) mobility

For environments that prioritise mobility and speed over protection, the army utilises the Bushmaster infantry mobility vehicle (IMVs).[108] The Ministry of Defence has recently placed an order for 1275 new IMVs, to be produced by Iveco.[109] The vehicles, named Medium Tactical Vehicle (MTV), are due to commence entering service in 2022.[110] Multiple versions of the Mercedes-Benz Geländewagen are in use across the army, including light armoured combat versions such as the G280 CDI.[111] The Volkswagen Amarok has replaced a large portion of the Mercedes-Benz fleet that was used for day-to-day utility work and peace time operations.[112] Special operations forces (SOF) operate the Dutch-made Defenture VECTOR which is tailor-made for special operations.[113]

Engineers and utility

Engineer regiments employ several specialist engineering vehicles based on Leopard 1 and Leopard 2 tanks such as the Buffel armoured recovery vehicle, the Leguaan armoured vehicle-launched bridge and the Kodiak combat engineering vehicle.[114][115][116] The army employs a variety of (logistical) utility vehicles, including four-, six-, ten- and fifteen-tonne trucks, mainly produced by DAF and Scania). Electronic warfare and CBRN defence units operate the TPz Fuchs armoured personnel carrier.[117] In addition, during operations that require a high degree of mobility, army personnel have access to Luchtmobiel Speciaal Voertuig, KTM motorcycles and Suzuki quads.[118][119][120]

Unmanned aerial vehicles

Multiple types of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are operational within the army. This includes the Black Hornet Nano, AeroVironment RQ-11B DDL Raven, Boeing Insitu ScanEagle, AeroVironment Wasp III, AeroVironment RQ-20 Puma and Boeing Insitu RQ-21 Blackjack UAVs.[121] A large share of UAVs are operated by the 107 Aerial Systems Battery of the Joint ISTAR Command.[122]

Defenture VECTOR

Defenture VECTOR

References

- The International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 2020). The Military Balance 2020. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780367466398.

- Kos, Jelmer (2 April 2019). "Martin Wijnen wordt nieuwe commandant landstrijdkrachten". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Dekker, Willem (16 July 2017). "Drenthe blijkt goede kweekvijver voor militaire top van Defensie". Dagblad van het Noorden. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- van Elk, Bert (3 March 2020). "Ervaren korporaals stromen door: Onderofficiersbestand aan het Infuus". Landmacht. 02. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Kamphuis, P.H.; Schoenmaker, B. (2014). "200 jaar Koninklijke Landmacht: Van blooded tot blooded" (PDF). Militaire Spectator. 183 (4). Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Missie-overzicht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Taken van de krijgsmacht". www.rijksoverheid.nl. Rijksoverheid. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "11a. Integriteit". Algemeen militair ambtenarenreglement. Overheid.nl. 25 February 1982. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

Ik zweer trouw aan de Koning, gehoorzaamheid aan de wetten en onderwerping aan de krijgstucht. Zo waarlijk helpe mij God Almachtig

- "Taken landmacht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Bennhold, Katrin (20 February 2019). "A European Army? The Germans and Dutch Take a Small Step". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Division Schnelle Kräfte". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Hoffmann, Lars (8 August 2017). "German Armed Forces To Integrate Sea Battalion Into Dutch Navy". defensenews.com. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "Duitse luchtverdedigingseenheid onder Nederlands bevel geplaatst". NU.nl. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Zwitzer, H.L. (1991). 'De militie van den staat': Het leger van de republiek der verenigde Nederlanden. Uitgeverij de Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 9789068810202.

- van Nimwegen, Olaf (October 2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. London, United Kingdom: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835752.

- Deen, Femke (January 2006). "De professionalisering van het leger tijdens de Tachtigjarige Oorlog: 'De discipline was zo strikt als in een klooster'". Historisch Nieuwsblad. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Jacops, Wiel (2018). ‘Eene onvermijdelijke noodzakelijkheid’: 225 jaar rijdende artillerie 1793–2018. 's-Gravenhage: Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie. ISBN 9789071957475.

- van der Spek, Christiaan (2016). Sous les armes: Het Hollandse leger in de Franse tijd (1806–1814). Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers. ISBN 9789058756985.

- Hay, Mark Edward. "The Dutch Experience and Memory of the Campaign of 1812: a Final Feat of Arms of the Dutch Imperial Contingent, or: the Resurrection of an Independent Dutch Armed Forces?". Napoleonic Scholarship Journal. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Snapper, F. (1972). "De legervorming in Nederland tussen 1813 en 1940" (PDF). Militaire Spectator. 01. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Geschiedenis landmacht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Nater, J.P. (1980). De tiendaagse veldtocht: de Belgische opstand 1830/1831. Haarlem: Fibula-Van Dishoeck. ISBN 9022838684.

- "1914–1940: Nederland neutraal". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Amersfoort, Herman; Kamphuis, Piet (2012). Mei 1940: De strijd op Nederlands grondgebied. Amsterdam: Boom. ISBN 9789461057020.

- de Jong, Loe (1970). Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog: 1939–1945 (Deel 3: Mei '40 ed.). 's-Gravenhage: Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie.

- "Oprichting". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "No.2 (Dutch) Troop". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Isby and Kamps, 1985, 317

- "1945–1949: Van Nederlands-Indië naar Indonesië". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Harinck, Christiaan (26 July 2017). "Wie telt de Indonesische doden?". De Groene Amsterdammer. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Klep, Christ; van Gils, Richard (2005). Van Korea tot Kabul: De Nederlandse militaire deelname aan vredesoperaties sinds 1945. 's-Gravenhage: Sdu Uitgevers. ISBN 9012109159.

- Structural details in 1985 can be seen at http://www.orbat85.nl/, accessed April 2012.

- a-d quoted from Felius, Einde oefening. Infanterist tijdens de Koude Oorlog (Arnhem: Uitgeverij Quintijn, 2002), 305, via Hans Boersma, I (NL) Corps, accessed 4 April 2012

- "United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)". www.defensie.nl. Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ten Cate, Arthur (2004). De laatste divisie: de geschiedenis van 1 Divisie '7 December' na de val van de Muur 1989–2004. 's-Gravenhage: Sdu. ISBN 9012106699.

- Seegers, Jules (19 December 2013). "Leopard-tanks toch verkocht, Defensie vindt in Finland alsnog koper". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Verjaard materieel Defensie blijkt onverkoopbaar". De Volkskrant. 23 October 1998. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 2011-04-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- dvhn.nl Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)

- Niewold, Michaël (28 May 2015). "Zo slecht is ons legermaterieel". RTL Z. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Defensie-uitgaven verder afgenomen". www.cbs.nl. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Walenkamp, Keetje (23 January 2017). "Een strijd om de defensiebegroting". Militaire Spectator. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) en de United Nations Peace Forces (UNPF)". www.defensie.nl. Nederlands Instituur voor Militaire historie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Karremans, Thom (December 1998). Srebrenica Who Cares?: Een puzzel van de werkelijkheid. Arko Sports Media. ISBN 9789072047540.

- Bowcott, Owen; Borger, Julian (22 November 2017). "Ratko Mladić convicted of war crimes and genocide at UN tribunal". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Srebrenica – Reconstruction, background, consequences and analyses of the fall of a 'safe' area" (PDF). NIOD Institute for War-, Holocaust- and Genocide Studies. 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederlands aandeel inzet Irak". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Inzet in Irak" (PDF). www.defensie.nl. Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederlandse missie in Irak officieel geëindigd". De Volkskrant. ANP. 7 March 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederland wil samen met België IS bekampen achter front in Irak". Gazet van Antwerpen. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- van Langendonck, Gert (17 July 2017). "Instructeurs leren geharde peshmerga beter schieten". NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Militaire bijdrage Nederland in Irak". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "De opbouw van ISAF in Afghanistan sinds 2001". Het Parool. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Eindevaluatie Nederlandse bijdrage aan ISAF, 2006 – 2010". www.tweedekamer.nl. Cabinet of the Netherlands. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Dimitriu, G.R.; Tuinman, G.P.; van der Vorm, M. (2012). "Operationele ontwikkeling van de Nederlandse Special Operations Forces, 2005–2010" (PDF). 108 (3). Retrieved 5 May 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Derksen, Sebastiaan. "De Nederlandse missie in Uruzgan: 'COIN gekortwiekt?'" (PDF). Universiteit Leiden. Retrieved 5 May 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vrijsen, Eric (5 January 2008). "Het gevecht om Chora" (PDF). Elsevier. 1. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederlanders vochten mee in operatie Medusa". De Volkskrant. ANP. 15 September 2006. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Son of Top Dutch General Is Killed in Afghanistan". The New York TImes. Associated Press. 19 April 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "ISAF Key Fact and Figures Placemat" (PDF). www.nato.int. NATO. 1 September 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Afghanistan". www.veteraneninstituut.nl. Veteraneninstituut. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Einde missie Uruzgan: kleine ceremonie". De Volkskrant. ANP. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederlandse bijdrage Resolute Support". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Brasser, Bianca (7 May 2019). "KCT mee met Afghanen: Shana ba shana". Landmacht. 04. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Nederlandse commando's in heel Afghanistan". De Telegraaf. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- de Ridder, Marlous (10 June 2014). "Commando's welkom in Gao: Special Forces nog nooit zo in de openbaarheid". Landmacht. 05. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Kuijl, Wouter (23 January 2019). "De All-Sources Information Fusion Unit in Mali en de Dutch Approach". Militaire Spectator. 188 (1). Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Militairen Luchtmobiele Brigade sluiten missie in Mali af". RTV Drenthe. 28 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Dutch minister resigns over deaths of Mali peacekeepers". BBC News. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Mortierongeval Mali". Onderzoeksraad voor Veiligheid (Dutch Safety Board). 28 September 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- van 't Einde, Tom (1 May 2019). "Missie in Mali voorbij, militairen terug naar Nederland". EenVandaag. AVROTROS. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "200 Nederlandse militairen naar Litouwen". Leeuwarder Courant. 6 July 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Akkerman, Floris (29 December 2018). "De NAVO in Litouwen: "Wat zou Rusland toch moeten met ons?"". Reformatorisch Dagblad. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Oostflank NAVO-gebied: Wat doet Nederland?". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Selles, Jaap (6 January 2020). "Kanonnen uit 't Harde moeten half jaar Russen op afstand houden in Litouwen". De Stentor. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Organisatiestructuur landmacht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Dienstplicht". www.rijksoverheid.nl. Rijksoverheid. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Koning Willem-Alexander (2 June 2016). "Traditiebesluit Koninklijke Landmacht". Overheid.nl. www.overheid.nl. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Calmeyer, M.R.H. (1948). "De Koninklijke Landmacht na de bevrijding: terugblik en uitblik" (PDF). Militaire Spectator. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Eenheden landmacht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Nederland krijgt leger zonder tanks". nu.nl. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "Geschichte". German Army official website (in German). Bundeswehr. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "Tenuen voor militairen van de Koninklijke Landmacht: Voorschrift (2 -1593" (PDF). www.defensie.nl. Commandant Landstrijdkrachten. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Militairen krijgen interim-gevechtskleding voor uitzendingen". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Commando's krijgen nieuw gevechtstenue". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "De rol van militaire muziek". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Vaandels en standaarden bij de Koninklijke Landmacht". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Koningin Juliana (20 June 1956). "Besluit volgorde verhouding rangen en standen zee-, land- en luchtmacht". Overheid.nl. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "De rangonderscheidingstekens van de krijgsmacht" (PDF). www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Colt C7-geweer". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "HK416-aanvalsgeweer en HK417-scherpschuttersgeweer". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Glock 17-pistool". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Accuracy-scherpschuttersgeweer (antipersoneel)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Twigt, André (5 March 2019). "Stilzitten en luisteren: Snipertraining Gebirgsjäger is Spitzenklasse!". Landmacht. Ministerie van Defensie. 02. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Barrett-scherpschuttersgeweer (antimaterieel)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Minimi-licht machinegeweer". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "MAG-middelzwaar machinegeweer". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Browning M2-zwaar machinegeweer". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Mortieren (60-, 81- en 120mm)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Leopard 2A6-gevechtstank". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "CV90-infanteriegevechtsvoertuig". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Boxer-pantserwielvoertuig". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Fennek-verkenningsvoertuig". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Pantserhouwitser 2000NL". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Patriot-luchtverdedigingssysteem weer van deze tijd". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. 15 July 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Patriot-luchtverdedigingssysteem". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Army Ground Based Air Defence System". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Bushmaster". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Iveco Defence Vehicles awarded contract to deliver a new generation of medium multirole protected vehicles to Dutch Armed Forces". Jane's. 12 September 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Verwervingsvoorbereiding (D-fase) van het project 'Voertuig 12kN overig en Remote Controlled Weapon Station (RCWS)'". www.tweedekamer.nl. Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- "Mercedes-Benz 290GD". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Amarok-pick-uptruck". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Vector-terreinwagen (SOF)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Leopard 2-bergingstank (Buffel)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Brouwer, Evert (17 December 2019). "Legua(a)n komt eraan: Succesvol samenwerkingsproject met Duitsland". Materieelgezien. Ministerie van Defensie. 10. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Leopard 2-geniedoorbraaksysteem (Kodiak)". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Fuchs-pantservoertuig". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Luchtmobiel Speciaal Voertuig". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "KTM-motorfiets". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Suzuki King Quad". www.defensie.nl. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Brouwer, Evert (12 May 2017). "Integrator komt eraan: Nieuwe UAV's voor krijgsmacht". Materieelgezien. Ministerie van Defensie. 03. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Wolting, Jaap (5 November 2019). "'Lege' Integrator optimaal voorbereid op innovaties: Luxemburg lift mee op ervaring in 't Harde". Landmacht. Ministerie van Defensie. 09. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Army of the Netherlands. |

- Royal Netherlands Army, official website