Remi

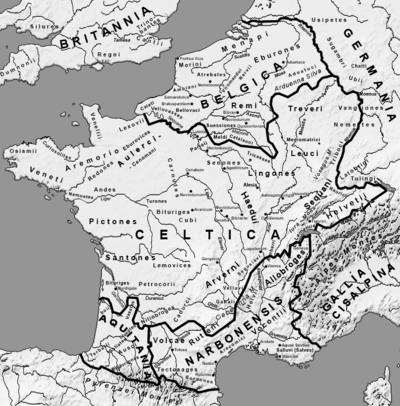

The Remi (Gaulish: "the first ones, the princes") were a Belgic tribe, dwelling in the Aisne, Vesle and Suippe river valleys, corresponding to the modern Marne and Ardennes and parts of the modern Aisne and Meuse départements.[1]

Name

They are mentioned as Remi by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[2][3] as Rhē̃moi (Ῥη̃μοι) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD) and Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[4][5] as Remos by Tacitus (early 2nd c. AD),[6] as Rhēmō̃n (Ῥημω̃ν) and Rhēmoĩs (Ῥημοι̃ς) by Cassius Dio (3rd c. AD),[7] and as Nemorum in the Notitia Dignitatum (5th c. AD).[8][9]

The name Remi ('the first ones, the princes') derives from Gaulish rēmos ('first, prince'), ultimately stemming from Proto-Celtic *preimos ('first, prince, chief'; compare with Welsh rwyf 'prince, chief' and Middle Cornish ruif 'king').[10][11][12]

The city of Reims, attested as civitate Remorum ca. 400 AD (Rems in 1284), is named after the Gallic tribe.[13]

Geography

Territory

The Remi dwelled in the Aisne, Vesle and Suippe valleys, with a heavy concentration in the middle Aisne valley.[1] Their territory was located south of the Suessiones.[14] As they were encircled by forests, however, the lands under their control nowhere bordered on neighbouring tribes.[1]

Settlements

La Tène period

Before the Roman conquest (57 BC), the villages of the Remi were located along natural pathways and terrestrial cross-ways at Nizy-le-Comte, Thugny-Trugny, or at Acy-Romance, occupied from the early 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD.[15] The rural areas of the Aisne valley were densely occupied and structured around trade relations with Mediterranean merchants, with large farms held by local aristocrats and bordered by numerous hamlets.[16]

In the late 2nd–early 1st centuries AD, a few oppida were erected at Bibrax (Vieux Laon, Saint-Thomas), Nandin (Château-Porcien), 'Moulin à Vent' (Voncq), La Cheppe, and 'Vieux Reims' (Condé-sur-Suippe/Variscourt).[16]

Roman period

At the beginning of the Roman period, the Remi moved away from the villages and oppida that were in unfavourable positions within the emerging economic system of the Empire. For instance, the oppidum of Saint-Thomas (Bibrax) was abandoned in the middle of the 1st century BC, whereas Le Moulin à Vent, which bordered the trade route between Reims and Trier, developed into the town of Voncq, attested as Vongo vicus in the 3rd c. AD.[17]

Durocortorum (modern Reims), a former oppidum probably built in the late 2nd–early 1st centuries AD and mentioned by Caesar in the mid-1st century AD, was promoted as capital of their civitas in the end of the 1st century BC.[18] The name of the settlement stems from the Gaulish duron ('gates', then 'enclosed town, market town').[19]

Secondary agglomerations of the Roman period are also known at Vervins, Chaourse, Nizy-le-Comte, Laon or Coucy-les-Eppes. Nizy-le-Comte, occupied at least until the end of the 4th century, probably reached around 80 hectares at its height.[20]

History

La Tène period

According to archaeologist Jean-Louis Brunaux, large-scale migrations occurred in the northern part of Gaul in the late 4th–early 3rd century BC, which may correspond to the coming of the Belgae. Those cultural changes, however, emerged later among the Remi. Whereas new funerary customs (from burial to cremation) are noticeable by 250–200 BC on the territories of the Ambi or Bellovaci, incineration did not occur before 200–150 in the Aisne valley.[21] The Remi were probably not regarded as culturally integrated to the Belgae by Caesar.[21]

At the time of the Roman conquest, the Remi had prospered from their local agricultural production and foreign trade, and they possessed a structured economic system with monetary issuance.[22] After a period of regression in the 4th–3rd centuries, trade between the Champagne and the Mediterranean regions recovered and gained in intensity during the second part of the 2nd century. A local landed nobility founded on agricultural and mining possessions emerged in the Aisne valley, and the Remi elite was rapidly influenced by the Latin culture through contacts with Roman merchants.[23] Wine, in particular, was imported in large quantity from southern Europe by the local Remi elite before the Roman conquest.[16]

Gallic Wars

During the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), under the leadership of Iccius and Andecombogius, the Remi allied themselves with Julius Caesar. They maintained their loyalty to Rome throughout the entire war, and were one of the few Gallic polities not to join in the rebellion of Vercingetorix.

When the Belgae besieged the oppidum of Bibrax (Saint-Thomas), defended by the Remi and their leader Iccius at the Battle of the Axona (57 BC), Caesar sent Numidian, Cretan and Balearic soldiers to avoid the seizure of the stronghold.[24]

Roman period

A founding myth preserved or invented by Flodoard of Reims (d. 966) makes Remus, brother of Romulus, the eponymous founder of the Remi, having escaped their fraternal rivalry instead of dying in Latium.[25]

Political organization

Until the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), the Remi shared a common cultural identity with the neighbouring Suessiones, which with they were linked by the same law, the same magistrates and a unified commander-in-chief. In reality, this virtual state of union between the two tribes probably leaned in favour of the Suessiones. The Remi asked the protection of the Romans by the time Caesar entered Gallia Belgica in 57 BC, thus gaining independence from a possibly asymmetrical relationship.[14][24]

Economy

In the second part of the 2nd century BC, as the result of early trade contacts with the Mediterranean world, and encouraged by a political will to build economic relations with Rome, the Remi were the first people to issue coins in Gallia Belgica.[26] Their oppida were responsible for the minting of coins in the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BC.[22]

La production d’une « petite monnaie » destinée à un véritable usage économique apparaît chez les Rèmes au moment où émerge un état structuré, à la fin de LT C1. Il s’agit des potins dits « à l’ange » Sch. 193 (fig. 2), datés peu avant 200 av. J.-C., dont le revers copie un didrachme romano-campanien frappé entre 265 et 242 av. J.-C[27]

Religion

Two pre-Roman sanctuaries located at La Soragne (Bâalons-Bouvellemont) and Flavier (Mouzon) attest the religious offering of miniature weapons. In another sanctuary (Nepellier, Nanteuil-sur-Aisne) were found Celtic sun crosses, destroyed weapons, coins, and human remains.[16] Nepellier dates back to 250–200 BC and continued to be used in the Roman period until its destruction during the Late Antiquity.[28]

During the Roman period, Mars Camulus was probably the principal god of the Remi.[29] Gallo-Roman sanctuaries are attested at Nizy-le-Comte, Versigny, and Sissonne.[30] A statuette of Jupiter with a wheel was found in Landouzy-la-Ville. Although it features distinct Gallic characteristics, the inscription honours the Roman god Jupiter and the Imperial numen.[30] Another inscription from Nizy-le-Comte was dedicated to Apollo.[30]

References

- Schön 2006.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:3

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:106

- Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:3:5

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:6

- Tacitus. Historiae, 4:68

- Cassius Dio. Rhōmaïkḕ Historía, XXXIX:1; XL:11

- Notitia Dignitatum. oc 11:34

- Falileyev 2010, p. entry 2279.

- Lambert 1994, p. 34.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 257.

- Busse 2006, p. 199.

- Nègre 1990, p. 156.

- Wightman 1985, p. 27.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, pp. 16, 27.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, p. 16.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, pp. 21, 25–26.

- Neiss et al. 2015, p. 171.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 156.

- Pichon 2002, p. 82.

- Pichon 2002, p. 74.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, p. 17.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, p. 13.

- Pichon 2002, p. 78.

- Michel Sot, “Les temps mythiques: les origines païennes et chrétiennes de Reims. I. Les origines païennes,” in Un historien et son Église au Xe siècle: Flodoard de Reims ([Paris]: Fayard, 1993).

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, pp. 13, 16.

- Neiss et al. 2015, p. 165.

- Lambot & Casagrande 1996, p. 22.

- Derks 1998, p. 97.

- Pichon 2002, p. 84.

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Derks, Ton (1998). Gods, Temples, and Ritual Practices: The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-254-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies (in French). Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambot, Bernard; Casagrande, Patrick (1996). "Les Rèmes à la veille de la romanisation. Le Porcien au Ier siècle avant J.-C". Revue archéologique de Picardie. 11 (1): 13–38. doi:10.3406/pica.1996.1885.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neiss, Robert; Berthelot, François; Doyen, Jean-Marc; Rollet, Philippe (2015). "Reims/Durocortorum, cité des Rèmes: Les principales étapes de la formation urbaine". Gallia. 72 (1): 161–176. ISSN 0016-4119. JSTOR 44744313.

- Pichon, Blaise (2002). Carte archéologique de la Gaule: 02. Aisne (in French). Les Editions de la MSH. ISBN 978-2-87754-081-0.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Remi". Brill’s New Pauly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)