Yongle Encyclopedia

The Yongle Encyclopedia or Yongle Dadian (simplified Chinese: 永乐大典; traditional Chinese: 永樂大典; pinyin: Yǒnglè Dàdiǎn; Wade–Giles: Yung-lo Ta-tien; lit.: 'Great Canon of Yongle') is a largely lost Chinese leishu encyclopedia commissioned by the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1403 and completed by 1408. It comprised 22,937 manuscript rolls[1] or chapters, in 11,095 volumes. Fewer than 400 volumes survive today,[2] comprising about 800 chapters (rolls), or 3.5 percent of the original work.[3] Most of it was lost in the 2nd half of the 19th century, in the midst of Western attacks and social unrests. Its sheer scope and size made it the world's largest general encyclopedia until it was surpassed by Wikipedia on September 9, 2007, nearly six centuries later.[4][5][6]

Background

Although known for his military achievements, the Yongle Emperor was also an intellectual who enjoyed reading.[7] His love for research led him to develop the idea of categorizing literary works into a reference encyclopedia, in order to preserve rare books and simplify research.[8][9] Instrumental to this undertaking was Emperor Yongle’s own transformation of the Hanlin Academy.[8] Prior to his reign, the Hanlin Academy was responsible for various clerical tasks, such as drafting proclamations and edicts.[8] Emperor Yongle decided to elevate the status of the Hanlin Academy, and began selecting only the highest-ranking recruits for the academy.[7] Clerical duties were relegated to the Imperial officers, while the Hanlin Academy, now full of elite scholars, began working on literary projects for the Emperor.[7]

Development

The Yongle Dadian was commissioned by the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–24) and completed in 1408.

In 1404, a year after the work was commissioned, a team of 100 scholars, mostly from the Hanlin Academy, completed a manuscript called A Complete Work of Literature.[8] Emperor Yongle rejected this work and insisted on adding other volumes.[8] In 1405, under Emperor Yongle’s command, the number of scholars rose to 2,169. Scholars were sent all over China to find books and expand the encyclopedia.[8] In addition, Emperor Yongle assigned his personal advisor, Dao Yan, a monk, and Liu Jichi, the deputy minister of punishment, as co-editors of the encyclopedia, supporting Yao Guangxiao.[10] The scholars spent four years compiling the leishu encyclopedia, under the leadership of general editor Yao Guangxiao.[11]

The scholars incorporated 8,000 texts from ancient times through the early Ming dynasty. Many subjects were covered, including agriculture, art, astronomy, drama, geology, history, literature, medicine, natural sciences, religion and technology, as well as descriptions of unusual natural events.[2]

The encyclopedia was completed in 1408[1] at the Guozijian in Nanjing (now Nanjing University). It comprised 22,937 manuscript rolls[1] or chapters, in 11,095 volumes, occupying roughly 40 cubic meters (1400 ft3), and using 370 million Chinese characters[2][12] — the equivalent of about a quarter of a billion English words (around six times as many as the Encyclopædia Britannica). It was designed to include all that had been written on the Confucian canon, as well as all history, philosophy, arts and sciences. It was a massive collation of excerpts and works from the entirety of Chinese literature and knowledge. Emperor Yongle was so pleased with the finished encyclopedia, that he named it after his reign, and personally wrote a lengthy preface highlighting the importance of preserving the works.[9]

Style

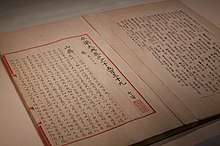

The encyclopedia’s physical appearance differed from any other Chinese encyclopedias of the time.[13] It was bigger in size, used special paper, and was bound in a “wrapped back” or (包背裝 bao bei zhuang) style.[14] The use of red ink for titles and authors, an ink exclusively reserved for the emperor, helped to confirm that the volumes were of royal production.[13] Each volume was protected by a hard-cover which was wrapped in yellow silk.[14] The encyclopedia was not arranged by subject, like other encyclopedias, instead it was arranged by 洪武正韻 (Hongwu zhengyun) a system in which characters are ordered phonetically/rhythmically.[14] The use of this system helped the reader find specific entries with ease.[14] Although book printing already existed in the Ming Dynasty, the Yongle Encyclopedia was exclusively handwritten.[14] Each handwritten entry was a collection of existing literature, some of which derived from rare and delicate texts.[14] The importance of the Yongle Encyclopedia was the preservation of such texts, and the vast number of subjects it covered.[14]

Reception

At the end of the Ming dynasty, scholars began to question Emperor Yongle's motives for not commissioning more copies of the encyclopedia, instead of keeping them in storage.[9] Some scholars, like Sun Chengze, a Qin scholar, theorized that Emperor Yongle used the literary project for political reasons.[9] At the time, Neo-Confucians were refusing to take civil service exams, or participate in any imperial duties, due to Emperor Yongle's violent usurpation of the throne.[9] Emperor Yongle's literary undertaking did attract the attention of these scholars, who eventually joined the project.[9] Because Emperor Yongle did not want a strictly Confucian point of view for the encyclopedia, Non-Confucian scholars were also included, and contributed to the Buddhism, Daoism, and Divination sections of the encyclopedia.[9] The inclusion of these subjects intensified the scrutiny against Emperor Yongle amongst Neo-Confucians who believed the encyclopedia was nothing but "wheat and chaff".[9] However, despite the varied opinions, the encyclopedia is widely regarded as a priceless contribution in preserving a wide range of China's historic works, many of which would be lost otherwise.

Disappearance

The Yongle Dadian was not printed for the general public, because the treasury had run out of funds when it was completed in 1408. It was placed in Wenyuan Ge (文渊阁) in Nanjing until 1421, when the Yongle Empire moved the capital to Beijing and placed the Yongle Dadian in the Forbidden City.[15] In 1557, during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor, the encyclopedia was narrowly saved from a fire that burnt down three palaces in the Forbidden City. A manuscript copy was commissioned by Jiajing Emperor in 1562 and completed in 1567.[11] The original copy was lost afterwards. There are three major hypotheses for its disappearance, but no conclusion was made:

- Destroyed in late Ming Dynasty. Li Zicheng, rebel leader, in 1644 overthrew the Ming Dynasty and took over the Ming capital, Beijing. A few months later, he was defeated by the coalition of Wu Sangui and Dorgon. Li burned the Forbidden City when he withdrew from Beijing.[16] The Yongle Dadian may have been destroyed in the fire.

- Buried with Jiajing Emperor. The time when the Jiajing Emperor was buried was very close to the time of completion of the manuscript copy. Jiajing Emperor died in December 1566, but was buried three months later, in March 1567.[16] One possibility is that they were waiting for the manuscript to be completed.

- Burned in Qianqing Palace fire.

The original manuscript of the Yongle Dadian was almost completely lost by the end of the Ming dynasty,[11] but 90 percent of the 1567 manuscript survived until the Second Opium War in the Qing dynasty. In 1860, the Anglo-French invasion of Beijing resulted in extensive burning and looting of the city,[3] with the British and French soldiers taking large portions of the manuscript as souvenirs.[11] 5,000 volumes remained by 1875, less than half of the original, which dwindled to 800 by 1894. During the Boxer Rebellion and the 1900 Eight-Nation Alliance occupation of Beijing, allied soldiers took hundreds of volumes, and many were destroyed in the Hanlin Academy fire. Only 60 volumes remained in Beijing.[11]

Current status

Fewer than 400 volumes survive today,[2] comprising about 800 chapters (rolls), or 3.5 percent of the original work.[3] The most complete collection is kept at the National Library of China in Beijing, which holds 221 volumes.[2] The next largest collection is at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, which holds 62 volumes.[17]

Sections of the Yongle Encyclopedia (sections 10,270 and 10,271) reside at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.[18][19]

51 volumes are in the United Kingdom held at the British Library, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London, and Cambridge University Library; The Library of Congress of the United States holds 41 volumes; Cornell University Library has 6 volumes; and 5 volumes are held in various libraries in Germany.[20][21]

See also

- Chinese encyclopedias

- Four Great Books of Song

- Gujin Tushu Jicheng

- Siku Quanshu

References

Citations

- Kathleen Kuiper (31 Aug 2006). "Yongle dadian (Chinese encyclopaedia)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 9 May 2012. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- "Yongle Encyclopedia". World Digital Library. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Foot, Sarah; Woolf, Daniel R.; Robinson, Chase F. (2012). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 2: 400-1400. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-923642-8.

- "Encyclopedias and Dictionaries". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (15th ed.). 2007. pp. 257–286.

- https://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2011/04/an-encyclopedia-finished-in-1408-that-contained-nearly-one-million-pages/

- http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/kindle/2014-10/27/content_18808071.htm

- Christos, Lauren. "The Yongle Dadian: The Origin, Destruction, Dispersal, and Reclamation of a Chinese Cultural Treasure." Journal of Library and Information Science 36, no. 1 (April 2010): 85. http://140.122.104.2/ojs/index.php/jlis/article/view/538.

- Jianying, Huo. "Emperor Yongle." China Today, April 2004, 58.

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry. Perpetual The Ming Emperor Yongle, University of Washington Press, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.oca.ucsc.edu/lib/ucsc/detail.action?docID=3444272.

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry. Perpetual The Ming Emperor Yongle, University of Washington Press, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.oca.ucsc.edu/lib/ucsc/detail.action?docID=3444272.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 604–5. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- 陈红彦 (2008). "国家图书馆《永乐大典》收藏史话" (PDF). National Library of China. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2016.

- Campbell, Ducan. "The Huntington Library’s Volume of the Yongle Encyclopaedia (Yongle Dadian 湛樂댕듕): A Bibliographical and Historical Note." East Asian History, no. 42 (March 2018): 1. http://www.eastasianhistory.org/42/campbell.

- Clunas, Craig, and Jessica Harrison-Hall. The BP Exhibition: Ming: 50 Years That Changed China. The British Museum, 2014.

- Lauren Christos (2010-01-04). "The Yongle Dadian: The Origin, Destruction, Dispersal and Reclamation of a Chinese Cultural Treasure". 圖書館學與資訊科學. 36 (1). ISSN 2224-1574.

- Lin, Guang (2017-02-28). "《永乐大典》 正本陪葬了嘉靖帝?". 《北京日报》. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- Yung-lo ta-tien (Vast Documents of the Yung-lo Era) National Palace Museum

- http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/kindle/2014-10/27/content_18808071.htm

- https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/culture/la-et-cm-huntington-library-chinese-yongle-encyclopedia-20141015-story.html

- "Experts Urge Collectors To Share World's Earliest Encyclopedia". Xinhua News Agency. April 2002.

- Helliwell, David. "Holdings of Yong Le Da Dian in United Kingdom Libraries" (PDF). Bodleian Library.

Sources

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, James B. Palais. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Guo Bogong (郭佰恭). Yongle dadian kao 永樂大典考. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1937.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yongle Encyclopedia. |

- Destruction of Chinese Books in the Peking Siege of 1900. IFLANET.

- China to Digitalize World's Earliest Encyclopedia. People's Daily Online. April 2002 - aspirations, pending approval.

- Biggest and Earliest Encyclopedia. chinaculture.org.

- Experts Urge Collectors To Share World's Earliest Encyclopedia. china.org.cn. April 2002.