Fishplate

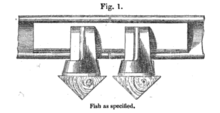

In rail terminology, a fishplate, splice bar or joint bar is a metal bar that is bolted to the ends of two rails to join them together in a track. The name is derived from fish, a wooden bar with a curved profile used to strengthen a ship's mast.[1] The top and bottom edges are tapered inwards so the device wedges itself between the top and bottom of the rail when it is bolted into place.[2] In rail transport modelling, a fishplate is often a small copper or nickel silver plate that slips onto both rails to provide the functions of maintaining alignment and electrical continuity.

History

The device was invented by William Bridges Adams[3] in May 1842, because of his dissatisfaction with the scarf joints and other systems[4] of joining rails then in use. He noted that to form the scarf joint the rail was halved in thickness at its ends, where the stress was greatest.[5] It was first deployed on the Eastern Counties Railway in 1844, but only as a wedge between the adjoining rails. Adams and Robert Richardson patented the invention in 1847,[6] but in 1849 James Samuel, the engineer of the ECR developed fishplates that could be bolted to the rails.[7]

Improvements

The moving blades of a set of points can be connected to the stock rails by looser than normal fishplates. This is called a heeled switch. Alternatively, the blade and stock rail can be a one piece heel-less switch, with a flexible thinned section to create the moving heel.

When railway lines are equipped with track circuits, or where the line is electrified for electric traction, the electrical connection provided by fishplates is poor and unreliable and has to be supplemented by bonding wire fixed to the two rails either side of the joint by spot welding or other means.

Welded joints

Even though fishplates strengthen the weak points represented by rail joints, improvements can still be made. For example, the joints can be welded together using the thermite welding process. In 1967, the Hither Green rail crash occurred on the Southern Region of British Railways when a rail fractured at its fishplate joint. Welded Rail installation was sped up due to this error, with strict procedures on concrete and wooden Sleepers.

Damage

On 12 July 2013, the last four cars of an SNCF Paris-Limoges train left the track while entering the Brétigny-sur-Orge station, killing seven people and injuring 32. The French land transport accident investigation bureau BEA-TT concluded in an interim report published on 10 January 2014 that "the derailment was caused by a fishplate obstructing the flangeway of an oblique crossing forming part of a double slip. Under the weight of the train travelling at 137 km/h, the fishplate had pivoted around the first of four bolts meant to hold it in place, the three others having come loose. The most likely cause of the bolts coming loose, says BEA-TT, were stresses caused by cracking in the cast steel crossing. This had caused the head of the third bolt to break off and the others to fail, one becoming unscrewed and the heads of the other two also shearing off." Recommendations included improving agency expertise in bolted track joints, clarification and reinforcement of regulations for defect detection and repair, and identification of switches and crossings where higher levels of maintenance and early renewal should be implemented.[8]

See also

- Rail lengths

- Tie plate

References

- "Fish 2". Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Morgan, C.D. (1946). "Permanent way". In Pendred, Loughan (ed.). The Engineer's Year-Book for 1946 (52 ed.). London: Morgan Brothers. p. 2015.

- Ransom 1990, p. 224.

- Ransom 1990, pp. 224-229.

- Manby 1857, p. 289.

- Manby 1857, p. 273.

- Marshall, C.F. Dendy (1963). A history of the Southern Railway Vol.1. Revised by R. W. Kidner. London: Ian Allan. p. 212.

- "Loose bolts to blame for Brétigny derailment". Railway Gazette.

- Ellis, C. Hamilton (1958). Twenty Locomotive Men. London: Ian Allan Ltd.

- Manby, Charles, ed. (1857). "Permanent Way". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. XV1 – via Google Books.

- Ransom, P.J.G. (1990). The Victorian Railway and How it Evolved. London: Heinemann.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fishplates. |

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Henry Williams Limited