Photography of Sudan

Photography of Sudan refers to both historical as well as to contemporary photographs taken in the cultural history of today's Republic of the Sudan. This includes its former territory of present-day South Sudan, as well as what was once Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and some of the oldest photographs from the 1880s, taken during the Turkish-Egyptian rule (Turkiyya). As in other countries, the growing importance of photography for mass media like newspapers, as well as for amateur photographers has led to a wider photographic documentation and use of photographs in Sudan during the 20th century and beyond. In the 21st century, photography in Sudan has undergone important changes, mainly due to digital photography and distribution through social media and the Internet.[1]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Sudan |

|---|

|

After the earliest periods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for which only foreign photographers have been credited with photographs or films of life in Sudan,[2] indigenous photographers like Gadalla Gubara[3] or Rashid Mahdi[4] added their own visions to the photographic inventory of the country from the 1940s onwards.[5] In 2017, the Sudan Historical Photography Archive in Khartoum started to build a visual inventory of everyday life from Sudan's independence in 1956 until the early 1980s.[6] - As documented in the comprehensive exhibition at the Sharjah Art Foundation on "The Making of the Modern Art Movement in Sudan", this period also includes Gubara and Mahdi as photographic artists during the country's prolific period for Modern Art.[5]

Since the end of World War II, professional photographers travelling the world, such as British photojournalist George Rodger, German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl or photographer Sebastião Salgado from Brazil have created photographic stories of rural ethnic groups in southern Sudan that became famous in the history of photography of Sudan.[note 1] More recently, developments in tourism, global demand for photography in mass media and the digital media of the 21st century have allowed an increasing number of Sudanese and foreign photographers to closely observe and record life in Sudan.

Colonial period - from pictures of 'natives' to real people

The earliest existing photographs from Sudan were taken from the 1870s onwards by British, Austrian, French or other foreign photographers and serve as documents of life in Africa or the colonial enterprise. Among other archives, the Digital Collections of the New York Public Library present a number of such early photographs taken in the Sudan.[7] An archive of several thousand photographs, mainly taken by British officials and visitors during the years from 1899 and up to the 1950s, is kept at the Sudan Archive at Durham University in the UK. [note 2] The same university also holds several other archives of British colonial officers, including photographs from various cities and regions of Sudan, with an online catalogue.[8]

In the 1880s, the Austrian explorer and photographer Richard Buchta published several books in German about his travels along the Nile, including a large number of photographs of ethnic people in southern Sudan.[note 3] At the turn of 1884/85, the Italian-British photographer Felice Beato documented the unsuccessful Nile Expedition of the British Army that came to the aid of Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, who was besieged by Mahdist forces. [note 4] After the short-lived Mahdist State, the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan provided new opportunities for photographs of British military or other officials. At that time, the early technology of photography was extremely difficult and expensive to use, as large format cameras and glass plates were used. [note 5]

In 1912–1913, new photographic technology in Sudan was evn used for aerial photography in archaeology, when British entrepreneur and amateur archaeologist Sir Henry Wellcome applied his automatic kite trolley aerial camera device during excavations at Jebel Moya, documented by several other photographs on this archaeological campaign.[9] [note 6]

A critical appreciation of these early non-Sudanese photographers and their clients' interest in exotic images of Sudan is expressed in the following quote by the Danish researcher Elsa Yvanez:

In Sudan, many photographs have been produced by British citizens posted in Khartoum and elsewhere during the Anglo-Egyptian condominium (1899-1956). As thousands of other Europeans through the colonial empires, the British directed their cameras to the "typical scenes" of Sudanese life: open-air markets, views of the Nile, fishing scenes, wild and natural landscapes and, above all else, the Sudanese people themselves. Many of these photographs where then edited as postcards (notably by the Gordon Stationary and Bookstores in Khartoum). Circulating through the colonies, Europe, and America, these pictures form an evocative, exotic and fascinating portrait of the Sudanese people.

— Elsa Yvanez, Sudanese Clothing Through the Modern Lens[10]

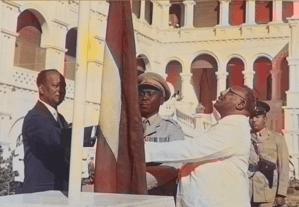

As far as has been documented, one of the first professional Sudanese photographers and film cameramen, was Gadalla Gubara, a pioneer of cinema in Sudan and Africa at large.[11][12] During and after WWII, he filmed and photographed many current events, one of them being the raising of the Sudanese flag on the Day of Independence.[13][note 7] Another early Sudanese photographer was the self-taught photographer Rashid Mahdi.[note 8][14] The French photographer Claude Iverné, who himself created photo stories in Sudan,[15][16] called Rashid Mahdi "certainly the most sophisticated and one of the major African photographers of the XXth century." On his webpage, which claims to present a collection of about 12.000 digitized images from 1890 until now,[17] Iverné has published many photographs by Rashid Mahdi, both from Mahdi's own collection as well as from the Musée du quai Branly in Paris.[18] - In their article An Outline History of Photography in Africa to ca. 1940, authors David Killingray and Andrew Roberts have noted an important change of representation in photographs of Africans in cities during the 1930s, calling them pictures of people, not 'natives'.[19]

George Roger and his photo stories of the Nuba and Latuka

A professional Western photojournalist, interested in traditional lifestyles in Africa was George Rodger, a founding member of Magnum Photos.[20] His photographs made in 1948 and 1949 of the indigenous people of the Nuba mountains, in the Sudanese province of Kordofan, and the Latuka and other tribes of southern Sudan, have been called by the editor of the book Nuba and Latuka. The Colour Photographs,[21] "some of the most historically important and influential images taken in sub-Saharan Africa during the twentieth century". As Rodger wrote several years later, "When we came to leave the Nuba Jebels (mountains), we took with us only memories of a people ... so much more hospitable, chivalrous and gracious than many of us who live in the 'Dark Continents' outside Africa."[22] In 1951, Rodger published his photo essay in the widely read magazine National Geographic.[23] His pictures later prompted controversial German photographer and filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl to travel to the Nuba mountains for her own photo stories on the Nuba people.[24]

Post-independence (1956-2010)

Sudan Historical Photography Archive – documenting social changes

In a recent attempt to collect and publish historical photographs, the Sudan Historical Photography Archive at the History Department of the University of Khartoum started in 2017 to build a library of images on Sudanese history since the middle of the 20th century. According to the archive's webpage, "this library includes images and books that display all parts of Sudanese history from the 1950s and 60s, including the beginnings of Khartoum University, religious activities of Sudanese Sufi orders, prominent politicians, musicians, athletes, and daily life." These photographs are accessible both in the department as well as online.[6]

The Golden Years of photography (1950s-early 1980s)

The years before Sudan's independence in 1956 and up to the early 1980s have been described as a prolific period for cultural life in Sudan, "including literature, music, and theatre to visual and performing arts."[25] Many Sudanese photographers of this important era are presented in English with a short biography and pictures on the French website Elnour,[26] such as Abbas Habib Allah, Ahmed Omar Addow, Djoua, Fouad Hamza Tibin,[27] Mohamed Yahia Issa,[28] Madani A A Gahory, Mohamed Abdarassul, Amin Rashid, Mohamed Adam Anagha, Omar Yahia Barram, Osman Hamid Khalifa, Richard Lokiden Wani or Shogui. Photographs by Gadallah Gubara and Rashid Mahdi have also been included in the comprehensive exhibition at the Sharjah Art Foundation on "The Making of the Modern Art Movement in Sudan" in 2017.[5]

Another important recognition of photography from Sudan, albeit as a “forgotten country”, was the presentation of a wide range of photographers, dating from 1935 to 2002, at the 6th African Photography Encounters 2005 in Bamako, Mali.[29]

Riefenstahl's photo books on the Nuba peoples

Based on several travels to the Nuba mountains in the 60s and 70s, when she was over 60 years of age, German photographer Leni Riefenstahl's photo books, comprising a total of 126 colour images of Nuba people in traditional settings, were published in 1974 as Die Nuba (The Last of the Nuba) and Die Nuba von Kau (The People of Kau). For some of her photographs and film scenes, Riefenstahl relied on Sudanese cameraman Gadalla Gubara, who accompanied her to the Nuba mountains.[30] Both photo books became international bestsellers and attracted much attention to the archaic lifestyle of these tribes in difficult accessible regions of Sudan.[31] Perhaps the most well-known critical reaction to Riefenstahl's photography of the Nuba came from the American intellectual, Susan Sontag. Based on Riefenstahl's earlier fascination with strong, healthy human bodies and her propaganda films for the government of Nazi Germany during the 20s and 30s, Sontag scrutinized the "fascist aesthetics" of these photo books in her widely read essay "Fascinating Fascism". Writing in the New York Review of Books in 1975, she stated: "The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets". This kind of criticism of the foreigner's view and interpretation of archaic African lifestyles was joined by her collection of essays On Photography, where Sontag argues that the proliferation of photographic images had begun to establish a "chronic voyeuristic relation" of the public.[32]

Travel photography and photojournalism

With the rise of colour photography, so-called coffee table books and illustrated magazines specialising on lavish photo essays and international tourism, various styles of documentary photography evolved, including photo stories about Sudan's historic heritage, such as the Nubian pyramids.[33] The wide interest in and social repercussions of travel photography do not only apply to professional photographers, but increasingly to tourists and their private, amateur photography.[34] The increase in numbers of tourists, taking photos rather than really observing or interacting with their travel destinations, has also raised criticism of unethical behaviour of photographers, especially with respect to taking photographs in non-Western countries, and of creating "exotic visions" of foreign cultures.[35] Sudan being one of the less visited, but more "exotic" destinations, is no exception to this. [note 9]

After having visually documented the culture of the Dinka people in South Sudan since the 1970s, American photographers Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher have earned renown for their aesthetically crafted images of the Dinka's ancient ways of cattle raising. Their photo essay is extensively presented online on Google's website Arts & Culture, providing viewers all over the world with an artistic impression of South Sudan.[36] Similar photos of the Dinka and their cattle are also part of the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado's well known images of archaic lifestyles in Eastern Africa.[37]

.jpg)

As many people in some regions of Sudan have been suffering from forced displacement, civil war or human trafficking, this also is regularly covered by photo journalists and published for the rest of the world. The departments for public relations of the big UN agencies like UNMIS, the United Nations Mission in Sudan for Peacekeeping, WHO or UNICEF, usually employ professional photographers from abroad for their photo reports. In some cases, however, Sudanese self-trained photographers like Sari Omer have also been employed for this kind of documentary photography, using their cultural knowledge of the populations concerned.[38]

In 1993, a shocking picture of a child, lying lifeless on the ground, and observed by a vulture sitting nearby, was published worldwide as a reminder of the human catastrophy in southern Sudan. The photographer Kevin Carter, a South African photojournalist, became known for this harrowing picture, called "The vulture and the little girl". According to questions about this assignment, Carter later said that he was shocked by the situation he had just photographed, and had chased the vulture away.[note 10] The following year, Carter won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for this picture, which had raised the concerns of many people about the ethical behaviour of the photographer and the publishers.[39][40]

The 2010s and beyond

.jpeg)

Digital photography: a new generation

Even though there are no institutions for teaching photography in Sudan, the new technical possibilities of digital photography, image editing and using the Internet for learning and sharing of photographs have made it possible for a growing number of Sudanese to train themselves in photography.[1] As in other countries, the spread of affordable mobile phones and Internet tariffs have led mostly younger Sudanese to start experimenting with digital cameras or mobile photography and to share their pictures or videos on social media.[41]

In 2009, an informal group of aspiring photographers created the "Sudanese Photographers Group" [41] on Facebook. The idea for this group was to have an easily accessible, virtual place for all interested photographers to meet and share ideas. In 2012, they decided to focus seriously on the art of photography and found a partner for setting up workshops in the German cultural centre in Khartoum. These workshops were conducted by invited professional photographers from Germany, South Africa and other African countries and repeated for several years, with assignments and meetings of the photographers in between the workshops. Out of these efforts for continued training, several photo exhibitions called Mugran Photo Week[42] were organized. Since then, some of the largely self-taught photographers have been invited to international exhibitions like the African Photography Encounters in Bamako, and some of the photographers have received grants to study abroad. One example for this are the Centers of Learning for Photography in Africa (CLPA), a growing network of independent photography training structures that have included photographers like Ala Kheir and others from Sudan, as well as photographers from other African countries.[43]

Commercial challenges and political expression

An important limiting factor for professional photographers in Sudan is the low demand for commercial photography. Noteworthy companies using professional photographs of Sudanese settings are DAL Group, Sudan's largest company,[44] that especially promotes Sudanese food products and local traditions,[45] as well as major internet providers like MTN,[46] or Zain.[47] Despite such constraints, there are nowadays many Sudanese freelance photographers experimenting with all kinds of photography, ranging from street photography to fine-art photography or even experimental photography.[48]

After the changes in public life due to the Sudanese revolution of 2018/19, new chances for artistic expression, public action or citizens's involvement in society are opening up. [note 11] The importance of photographs for expressions of political participation became evident by the iconic picture of Sudanese student Alaa Salah, who gained world-wide media attention through a picture of her taken during protests in 2019 by amateur photographer Lana Haroun on her smartphone.[49][50]

Another example is a photograph by Japanese photographer Yasuyoshi Chiba of Agence France-Presse, showing a young man in Khartoum reciting protest poetry, while demonstrators chant slogans calling for civilian rule, was selected as World Press Photo of the Year 2020.[51]

Contemporary photographers

Some of the notable contemporary Sudanese photographers of today include the professional photojournalists Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah, who has covered Sudan for Reuters multimedia news for more than 15 years and also is known for his imaginary fine-art photography,[52] and Ashraf Shazly,[53] who works for AFP/Getty Images in Khartoum.

Other notable photographers, mainly active in non-commercial photojournalism, like street photography or documenting cultural life through fashion or other lifestyles, are Ala Kheir,[54] Mohamed Altoum,[55] Hisham Karouri, Sharaf Mahzoub, Nagi Elhussain, Sari Omer, Atif Saad, Muhammad Salah,[56] Wael Al Sanosi aka Wellyce, or Ahmad Abushakeema[57] and the female photographers Ola Alsheikh,[58] Salma Alnour,[59] Soleyma Osman, Duha Mohamed, or Eythar Gubara.[note 12]

Most of them are members of the Sudanese Photographers Group, and have been part of Sudan's upcoming generation of photographers since the 2010s.[60]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Photographs of Sudan. |

- 155 Historical photographs by Richard Buchta in the online collection of the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna (with free downloads, enlarged viewing, sharing on social media)

- Library of Congress Digital Collections: Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph Collection, with 186 images, almost all taken in 1936

- Photographs from the Sudan Historical Photography Archive

- Photographs from Claude Iverné: Bilad es Sudan, a 2017 exhibition of images by the French photographer Claude Iverné, from New York’s Aperture Gallery

- Claude Iverné, Alice Franck. Khartoum, Capitale en Mutation - a portrait of Khartoum during the 2000s, including documentary photographs by Claude Iverné (in French)

- FABA Vintage: Portraits from Sudan, 1950s-1970s

- A history of the Sudans – in pictures since independence (The Guardian, 8 December 2014)

- The many faces of modern Sudan - in pictures

- Many Rivers, One Nile - Photo-Slide-Show of Mugran Foto Week 2014

- City in Change: Photographic Stories from Khartoum, Mugran Foto Week 2015

- Mugran Photo Encounter, documentary video about exhibitions of creative photography, Mugran Foto Week 2015

- Photo story on Youth of today in Sudan by Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah, (published by Reuters in 2014)

Further reading

- Fox, Paul. An unprecedented wartime practice: Kodaking the Egyptian Sudan. Media, War & Conflict, vol. 11, 3: pp. 309-335. July 13, 2017

- Haney, Erin, (2010). Photography and Africa. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-382-6. OCLC 457149525.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Iverné, Claude. SudanPhotoGraphs Vol.1/6, 64 pages, 16 plates, 230 photographs, ISBN 978-2-9542914-0-6

- Iverné, Claude. Fouad Hamza Tibin, Mohamed Yahia Issa, Filigranes Editions, 2005, ISBN 2-35046-007-X

- Killingray, David and Roberts, Andrew: An Outline History of Photography in Africa to ca. 1940: History in Africa, Vol. 16 (1989), pp. 197-208, Cambridge University Press

- Schuman, Aaron and Steele-Perkins, Chris (eds.). Nuba and Latuka. The Colour Photographs. Prestel, Munich, Germany 2017, ISBN 978-3-7913-8322-4 (Photographs taken in 1948/49 by George Rodger)

- Riefenstahl, Leni. The Last of the Nuba. New York: Harper & Row, 1974, ISBN 978-0060135492

- Vokes, Richard and Darren Newbury. Editorial: Photography and African Futures. Visual Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, 2018

- Ward, John. Our Sudan - Its Pyramids and Progress. J. Murrey, 1905

Notes

- Compare, for example, the following quote: "Indeed, probably the best known books of photographs of the Sudan are of the Nuba, Leni Riefenstahl's The Last of the Nuba and People of Kao, ..." (pp. 59-60) in Daly, Martin W.; Hogan, Jane R. (2005). Images of Empire: Photographic Sources for the British in the Sudan. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-14627-3. and the chapter George Rodgers Koronga Nuba Wrestlers of Kordofan, South Sudan, 1949 (pp.18-19) in McCabe, Eamonn (2005). The Making of Great Photographs: Approaches and Techniques of the Masters. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2220-8.

- In their book, The Sudan: Photographs from the Sudan Archive, the authors have published 240 photographs, presenting "events of historical or military significance, feats of engineering, and the daily life and recreation of the Sudanese and their temporary rulers." Daly, M. W.; Forbes, L. E.; Archive, Durham University Library Sudan (1994). The Sudan: photographs from the Sudan Archive, Durham University Library. Garnet Publishing.

- For his works, see the list in the article on Richard Buchta. There is a large selection of his photographs at

- In the book "Felice Beato: A Photographer on the Eastern Road", the authors give the following short account: "1885 - Beato travels to the Sudan to photograph the events of the Mahdist rebellion against the British, but arrives three months after the major events. On April 30, he meets Lord [Baron] G.J. Wolseley onboard ship from Suez to Suakim. (sic) He documents Wolseley's expedition to Suakim to superintend the withdrawal of the troops." Lacoste, Anne; Beato, Felice; Ritchin, Fred (2010). Felice Beato: A Photographer on the Eastern Road. Getty Publications. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-60606-035-3.

- In the article "Capturing the Light of the Nile" about the earliest photographs taken in Egypt, the author makes the following remarks about the photographic technology of the late 19th century: "The technology continued to improve and diversify, and the paper negatives were soon superseded by glass ones in the wet-collodion process that combined the sharpness of daguerreotypes with the reproducibility of calotypes."

- The 1905 book by John Ward, Our Sudan - Its Pyramids and Progress. J. Murrey, 1905 presents information and photographs on archaelogical sites in Sudan around the turn of the century and before.

- "Gubara and fellow scriptwriter Kamal Ibrahim, were the only cameramen to record Sudan's Independence on January 1st 1956. He captured the symbolic moments when democratically elected Prime Minister Ismail Al-Azhari walked from the parliament to the presidential palace and replaced the British and Egyptian flags with the blue, gold, and green flag of Sudan."

- In an article about the exhibition "The Khartoum School: The Making of the Modern Art Movement in Sudan (1945–present)" in Sharja, UAE, 2017, the author writes about photography in Sudan: "The exhibition highlights the work of two pioneer master-photographers, Rashid Mahdi and Gadalla Gubara, as well as other studio photographers, for example, Abbas Habib Alla, Mohamed Yahya Issa, Fouad Hamza Tibin, Osman Hamid Khalifa, Omar Addow, Richard Lokiden Wani and Joua, in the context of the historical linkages between photography, decolonisation and self-representation." Source: "Exhibitions - Sharjah Art Foundation". sharjahart.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- All tourists wanting to take photographs have to apply for a photography permit. Even with a photography permit, photographing military facilities, bridges, drainage stations, broadcast stations, public utilities, slum areas, and beggars is prohibited. Visitors must register at the Ministry of Interior within three days after arriving in Sudan. All foreigners traveling more than 25 kilometers outside of Khartoum must obtain a travel permit from the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs in Khartoum. Travellers without these permits may be detained by Sudanese authorities. Source: "Information for Travelers". U.S. Embassy in Sudan. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- Before taking his plane, Carter told Silva: "You won't believe what I've just shot! … I was shooting this kid on her knees, and then changed my angle, and suddenly there was this vulture right behind her! … And I just kept shooting – shot lots of film!" Then Carter told him that he had chased the vulture away. He told Silva he was shocked by the situation he had just photographed, saying, "I see all this, and all I can think of is Megan", his young daughter. A few minutes later, they left Ayod for Kongor. - In 2011, the child's father revealed that the child was actually a boy, called Kong Nyong, and had been taken care of by the UN food aid station. Source: Rojas, Alberto (21 February 2011). "Kong Nyong, el niño que sobrevivió al buitre|trans-title=Kong Nyong, The Boy Who Survived the Vulture". El Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

- Ala Kheir, one of the founders of the Sudanese Photographers Group, describes the difficult situation for photographers before the Sudanese revolution like this: "I think in the beginning of the 1990s, a lot of photojournalists took photos of what was happening in the country. The government reacted against those images that they did not want to be shown in the media. That is how the phobia started. This fear is still here, especially after the Arab Spring, as the regime saw what happened in other countries. When we go on a trip to take photographs, it is very common for us to be arrested and taken to the police station. It is not dangerous, but you lose time, they interrogate you. So they make sure you won’t be motivated to go out and take photographs."

- This list is by no means complete, but wants to name some of the most active and visible Sudanese photographers of today. Pictures of most of them can be found on Instagram.

References

- "Where the White Nile and the Blue Nile Meet | Contemporary And". www.contemporaryand.com. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- Sharkey, Heather J. (2003-03-18). Living with Colonialism: Nationalism and Culture in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. University of California Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-520-23559-5.

- "GADALA GUBARA | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Rashid MAHDI | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Exhibitions - Sharjah Art Foundation". sharjahart.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- "Creation of Historical Photography Archive at the History Department of Khartoum University". Endangered Archives Programme. 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Search results - "sudan photographs" - NYPL Digital Collections". digitalcollections.nypl.org. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- "Special Collections : The Sudan Archive at Durham - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- "Jebel Moya". Wellcome Library. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Yvanez, Elsa (2018-05-21). "Sudanese Clothing Through the Modern Lens". TexMeroe Project. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Studio Gad Archive (2017). "Biography". Studio Gad Archive - The heritage of the Sudanese filmmaker Gadalla Gubara. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- Korinth, Nadia. "The Omega Man: Gadalla Gubara and the half-life of Sudanese cinema". Bidoun. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- "Sudan: Gadalla Gubara - a Forgotten Filmmaking Legend". Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- "Exploring the Modern Art movement of Sudan | Africana Studies & Research Center Cornell Arts & Sciences". africana.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- salesaperture. "Claude Iverné: Bilad es Sudan". Aperture Foundation NY. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- "Claude IVERNÉ | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "About Elnour | ELNOUR" (in French). Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- "Rashid MAHDI | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Killingray, David; Roberts, Andrew (1989). "An Outline History of Photography in Africa to ca. 1940". History in Africa. 16: 197–208. doi:10.2307/3171784. ISSN 0361-5413.

- "The Nuba: Early Color Work • George Rodger • Magnum Photos". Magnum Photos. 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- "George Rodger Nuba & Latuka: The Colour Photographs | Magnum Photos Store". www.magnumphotos.com. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- Schuman, Aaron. "'Lost' early color photographs of Sudanese tribes published". CNN. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- "Wrestling Keeps 'Identity of the Nuba' Alive in Sudanese Refugee Camps". National Geographic News. 2014-11-28. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- "Leni Riefenstahl". www.holocaustresearchproject.org. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "Modernity and the Making of Identity in Sudan: Remembering the Sixties and Seventies | ICM". www.icm.arts.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- "PHOTOGRAPHERS | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "FHT-29b | ELNOUR" (in French). Retrieved 2019-12-23.

- "Fouad Hamza Tibin / Mohamed Yahia Issa | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- de Faÿs, Didier. "Sixth African Photography Encounters: Another World". Bidoun. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "GADALA GUBARA | ELNOUR". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "Invasion of thebody snatchers". John Ryle. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Sontag, Susan (1977). On Photography. London: Penguin Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780713911282.

- "Pictures of Sudan's forgotten Nubian pyramids". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "What Defines an Amateur versus a Professional Photographer?". Digital Photography School. 2015-02-01. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Travel Photography Ethics: When You Shouldn't Take That Picture". ExpertPhotography. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ""Dinka: Legendary Cattle Keepers of Sudan" – African Ceremonies". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Dinka group at Pagarau, Southern Sudan, Sebastião Salgado | Artspace.com". Artspace. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "UNICEF Sudan health & nutrition factsheet". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Obituary: Kevin Carter". The Independent. 1994-08-01. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- O'Hagan, Sean (2010-03-08). "Viewer or voyeur? The morality of reportage photography". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Where the White Nile and the Blue Nile Meet | Contemporary And". www.contemporaryand.com (in German). Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "MUGRAN FOTO WEEK 2016 – PHOTO EXHIBITION MODERN TIMES – Goethe-Institut Sudan". www.goethe.de. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Launch of the first phase of the ‚Survey on Photography Training and Learning Initiatives on the African Continent' | Contemporary And". www.contemporaryand.com. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- MANN, LAURA (2013). "'We do our bit in our own space': DAL Group and the development of a curiously Sudanese enclave economy". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 51 (2): 279–303. ISSN 0022-278X.

- "Sudan's Traditional Foods Festival: A Varied, Rich Nutritional Culture| Sudanow Magazine". sudanow-magazine.net. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Home – MTN". Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Photo Gallery". www.sd.zain.com. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- MUGRAN FOTO ENCOUNTER, 2015, presenting creative photography in Khartoum, Sudan, retrieved 2019-12-11

- Mezzofiore, Gianluca. "This woman has come to symbolize Sudan's protests". CNN. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- "Scared, worried and hopeful: A Sudanese photographer's view of the uprising". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Yasuyoshi Chiba | World Press Photo". www.worldpressphoto.org. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Abdallah, Mohamed Nureldin. "Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah". The Wider Image. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "World's Best Ashraf Shazly Stock Pictures, Photos, and Images – Getty Images". www.gettyimages.com. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Ala Kheir". Ala Kheir. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- Altoum, Mohamed; Estrin, James (2019-03-18). "A Photographer's Quest to Discover His Nubian Ancestry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "I Want To Be Visible | Arab Documentary Photography Program". arabdocphotography.org. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- Opaluwa, Ladi (2016-07-08). "Photography: a thousand faces of modern Sudan". This is africa. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "'I'm a woman with a camera – it surprises people'". 2018-08-22. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Salma Alnour". Salma Alnour. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "MUGRAN FOTO WEEK 2016 – PHOTO EXHIBITION MODERN TIMES – Goethe-Institut Sudan". www.goethe.de. Retrieved 2019-11-27.